Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Urban Farm Coming to Downtown Mobile

Urban Farm Coming to Downtown Mobile

Posted: Aug 13, 2017 10:50 PM CDT - By Lee Peck, FOX10 News Reporter

Shipshape Urban Farms hopes to break ground in near future and open in downtown Mobile later this year. Source: Dale Speetjens

Downtown Mobile Urban Farm

610 St. Michael Street may not look like much now, but the vacant lot will soon be home to something downtown Mobile has never seen.

Dale and Angela Speetjens are the masterminds behind Shipshape Urban Farms. Angela has a background in horticulture and will manage the farm. They'll use eight repurposed shipping containers, they'll grow the equivalent of a 20-acre farm on a 1/4 of an acre.

They'll use a process called hydroponics -- an efficient method of growing plants without soil in nutrient rich water. It maximizes the process from start to finish and takes the environmental pressures out of the equation.

"So normal farming you lose a lot of your crops to pests... here we are gong to be able to control the light, control the nutrients, we're going to be able to control the climate," explained Speetjens.

They expect to hire around four employees. Each container will require 8 to 15 hours a week of work.

Giving whole new meaning to homegrown, expect all your leafy green favorites 365 days a year.

"All year long -- we will produce every single week... We harvest close to 10,000 plants. Lettuce, herbs, salad mixes," said Speetjens.

They plan to serve local restaurants, farmers markets, and businesses in both Mobile and Baldwin counties. Customers will also be able to purchase produce through Shipshape's CSA program. CSA stands for "community Supported Agriculture. For an annual fee, CSA members will get a weekly basket of produce from the farm.

As a part of the mayor's innovation team, Speetjens knew there was a place for the urban garden in downtown Mobile.

"During that process, I worked on blight and vacant lots and I had a good idea where a lot of the vacant lots were in town," said Speetjens.

Speetjens expects their operation to spur other activity in the area.

"We are just one piece of the pie. If you look next to us... I can name 10 projects that are in some level of in the works," said Speetjens.

According to Speetjens, next door there's even talk of a restaurant and a brewery down the way.

"Most cities that are thought of as being walkable it's not a single street, it's a couple of streets and it won't take much for us to make connections between the St. Louis corridor and the Dauphin Street corridor -- a few in fills here and there - and we could really start seeing a boom. Doesn't take that much to make a big thing happen," said Speetjens.

Speetjens says they have a meeting with City of Mobile August 23 and will have a better idea of when they will break ground. He hopes they will be open by Christmas. For more information click here.

Urban Hydroponic Farms Offer Sustainable Water Solutions

Urban Hydroponic Farms Offer Sustainable Water Solutions

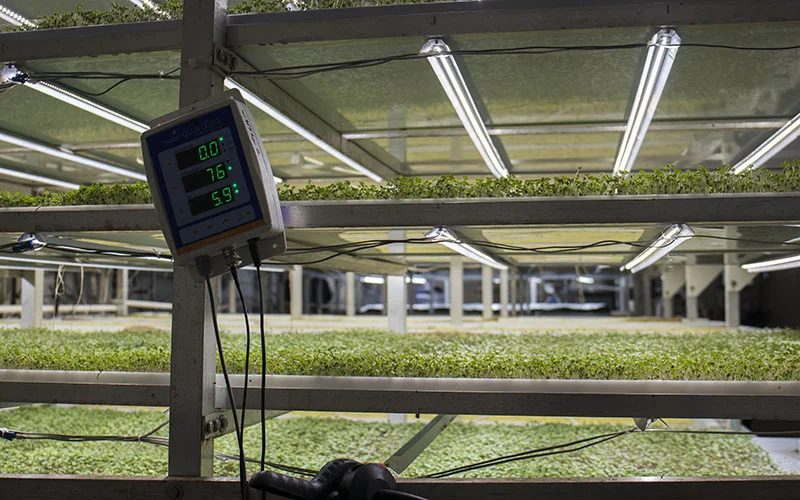

At Local Goods in California, Ron Mitchell’s monitoring system checks the plants’ water supplies for temperature, pH levels and electric conductivity. (Photo by Jackie Wang/News21)

By Nicole Tyau | News21 Tuesday, July 11, 2017

BERKELEY, Calif. – Tucked behind a Whole Foods in a corner warehouse unit, Ron and Faye Mitchell grow 8,000 pounds of food each month without using any soil, and they recycle the water their plants don’t use.

Hydroponic farming grows crops without soil. Instead, farmers add nutrients to the water the plants use. This method can produce a wide variety of plants, from leafy greens to dwarf fruit trees.

According to a study by the Arizona State University School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, hydroponic lettuce farming used about one-tenth of the water that conventional lettuce farming did in Yuma, Ariz. A similar study from the University of Nevada, Reno, found that growing strawberries hydroponically in a greenhouse environment also used significantly less water than conventional methods.

(Video by Jackie Wang/News21)

The Mitchells started production of Local Greens in February 2014. They primarily grow microgreens such as kale, kohlrabi and sprouted beans while using the same amount of water as two average households and the same amount of electricity as three in a month, they said.

“Who knows what you’re getting when you’re using soil?” Faye said. “Hydroponics is a fully contained system, so we know exactly what’s in our water, what we want in it and what we don’t want in it, and we can control that.”

Ron installed a water filtration system he customized. He removes fluoride, a common additive in municipal water, and chlorine, a common disinfection byproduct, before adding oxygen and other plant-specific nutrients.

At Local Greens, Ron and Faye Mitchell mostly cultivate microgreens, which grow to about 10 inches before they are cut and sold in the area. (Photo by Jackie Wang/News21)

To make use of the warehouse’s tall ceilings, the Mitchells stack six trays of microgreen seeds on top of each other. At one end, an irrigation spout controls the amount and type of water sent through the trays.

“Some plants don’t need or want nutrients because they have it in their seed,” Ron said. He explained that pea shoots don’t need any additives, but sunflowers require copious amounts of nutrients to grow quickly.

Ron Mitchell, 67, said the stacked trays inside his hydroponic farming facility in California allow them to grow twice as much. (Photo by Jackie Wang/News21)

The water the plants don’t use is captured at the other end of the tray and reused for the next watering, with the nutrients replenished as needed. The additional nutrients in the water are organic and naturally-occurring since they don’t have to spray pesticides or herbicides in their controlled warehouse environment, Faye said.

The number of greenhouse farms has more than doubled since 2007, according to the 2012 U.S. Department of Agriculture Census of Agriculture. Some hydroponics advocates see the practice as a solution to a global food and water crisis.

“I don’t think it could take over the farming industry entirely because of the types of plants and vegetables people want to eat,” Faye said. “But I definitely think it could make a dent in the farming industry and make its place and replace certain types of farms for a more efficient and, in some cases, less expensive system.

Editor’s note: This story was produced for Cronkite News in collaboration with the Walter Cronkite School-based Carnegie-Knight News21 “Troubled Water” national reporting project scheduled for publication in August. Check out the project’s blog here.

This Company Wants to Bring Soil-Free Farming to Restaurant Kitchens

Hydroponics have allowed garden vegetables to grow in novel places—from a pillar inside a Berlin grocery store to a veritable skyscraper of plants in Singapore.

This Company Wants to Bring Soil-Free Farming to Restaurant Kitchens

by Cathy Erway • 2017

Hydroponics have allowed garden vegetables to grow in novel places—from a pillar inside a Berlin grocery store to a veritable skyscraper of plants in Singapore. The fast-growing, soil-free farming method has been well-embraced in urban areas to produce crops using less water and space, since the plants are grown in a nutrient water solution, rather than in-ground. But rarely is it done within some of the buzziest places for the farm-to-table movement: a restaurant.

The team behind Farmshelf hopes that will soon change, and recently debuted three indoor hydroponic growing units at Grand Central Station’s Great Northern Food Hall. There, the chefs at the busy food market’s Scandinavian restaurant Meyers Bageri reach into the glass-walled cubicles to pick lemon basil for a garnish on their zucchini flatbread, and nearly a dozen varieties of baby lettuces are plucked for salads at the neighboring Almanak vegetable-driven café. And, as it would appear on recent visits, curious bystanders peer through the glass, agape at the billowy mixture of herbs and greens, illuminated by a ceiling of LEDs. Unbeknownst to the casual observer, the units are also outfitted with five cameras along every shelf, so that the Farmshelf team can monitor the plants’ progress from afar and adjust the system via a web application.

“The more plants we grow, the smarter we are about plants,” said Jean-Paul Kyrillos, Farmshelf’s Chief Revenue Officer. He explained that through their data collection, Farmshelf can optimize the growth and flavor of any plants that a client may want. “This is for someone who doesn’t want to be a botanist, or farmer. The system is automatic.”

“Plants can grow two to three times as fast using 90% less water than traditional in-ground farming”

That’s why Farmshelf hopes its units will be a boon for restaurants serving greens galore. Founded in 2016 by CEO Andrew Shearer, Farmshelf is just planting its roots in the New York City restaurant industry with its first partner, Meyers USA hospitality group. The startup was in the inaugural lineup of the Urban-X accelerator and is part of the Urban Tech program at New Lab. The company is looking to partner with more restaurants soon, and Kyrillos mentioned a restaurateur who was excited about the idea of placing a Farmshelf unit right in the dining room, as a partition.

Distribution is the last challenge of getting local food onto plates, and Farmshelf eliminates that entire process—no middleman, forager, or schleps to Union Square Greenmarket. Kyrillos is hopeful that the efficiency of hydroponics—where plants can grow two to three times as fast using 90% less water than traditional in-ground farming—will also convince restaurants of the value of placing such a system on-site. Then, there is the potential of growing ingredients that you could never get locally, like citrus; or mimicking the terroir of, say, Italy, through a special blend of nutrients and conditions within the units.

Green City Growers in Cleveland, OH, has a 3.25-acre hydroponic greenhouse. Photo by Flickr/Horticulture Group

With hydroponics, you can grow a plethora of vegetables, even root vegetables like turnips, carrots, radishes, but these take much longer, and thus not suited to the fast-paced restaurant environment Farmshelf is trying to service. Crops that take up a lot of space, like watermelon and pole beans, are also not ideal, as the point is for these systems to use space efficiently (though future designs of hydroponic units might be able to tackle this challenge). It's most cost-effective to grow delicate, highly perishable, expensive leafy greens than roots, which are quick to grow and easy to ship and store.

The possibilities seem endless. But, in an age when the small family farm is rapidly disappearing in the US—and faces further threat from a recent White House budget proposal that would eliminate crop insurance—would this technology take away business from local farms, which restaurants might otherwise buy from?

Hydroponics—The Future of Farming in Detroit?by Lindsay-Jean Hard

Kyrillos doesn’t see Farmshelf as a replacement for the local farmer. There are some six to eight months of the year where traditional farms can’t grow too many crops, so restaurants would buy leafy greens and other warm-season produce elsewhere. If anything, Kyrillos posited that it might chip away at business from some of the bigger food distributors.

But time will have to tell what best works for the soon-to-be users of Farmshelf. Right now, the company is hoping to sell restaurants at least three growing units to make a significant enough impact on its kitchen orders. Rather than leaving it at that, Farmshelf wants to work with restaurants through a sort of subscription-based service, supplying seeds for crops that the restaurant would like to grow and monitoring the growing process consistently. Could a chef go rogue, and use the unit to plant and harvest whatever, whenever he pleased? Perhaps—but that wouldn’t really be taking advantage of the full product, which the team estimates might cost around $7,000 per unit (a medium-sized restaurant might need three units, at $21,000), which would pay off in ingredient costs.

And how about home chefs? When will average consumers be able to place Farmshelf inside our cramped, outdoor space-free apartments? That’s in the vision for Farmshelf someday. Not just homes, but school classrooms or cafeterias could be future sites of these hydroponic shelves, Kyrillos suggested, offering an easy, indoor way to connect youngsters to the food on their plates. “Imagine children were watching food grow, all the time.”

TAGS: HYDROPONICS, TECHNOLOGY, ENVIRONMENT, GRAND CENTRAL

How Change Happens: Inspiring Examples from Urban Food Policy

How Change Happens: Inspiring Examples from Urban Food Policy

Many of us in the world of food policy are excited by what is happening in cities. Hundreds of municipalities are developing and delivering policies to improve the food system. Fortunately, extensive efforts to document them means we know a considerable amount about what they are doing—a whole host of activities, including improving public procurement, building greenbelts to address climate change, training organic gardeners, enabling rooftop gardens, innovating strategies to reduce food waste and improve food safety, cutting down on trans fats, introducing soda taxes, eliminating marketing in sports stadiums, and tackling food insecurity.

We know a lot less, though, about how cities are managing to do all this. When change—especially policy change—can be so extraordinarily difficult, how have cities actually made it happen?

This was the question behind a new report released this week from the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food). Looking in depth at four cities—Nairobi (Kenya), Belo Horizonte (Brazil), Detroit (USA), Amsterdam (the Netherlands)—and one city-region, the Golden Horseshoe (Canada), the report explores the nuts and bolts of policy making. Based on interviews, it shares the insights of people who have made urban food policies happen, so that others can make food policy happen in their cities, too.

Our findings? Cities are undoubtedly innovators in food policy but that this innovation happens through often quite mundane processes. It’s not always exciting; it happens mainly behind the scenes, but it matters a great deal for getting stuff done.

In Nairobi, for instance, we uncovered the fascinating story of how urban agriculture went from being perceived as a blight on the city to an asset that is positively promoted by the Nairobi Urban Agriculture Promotion and Regulation Act 2015. What brought about this U-turn was the sustained efforts of civil society to unify and amplify the voices of urban farmers and to build supportive relationships with national civil servants.

In Detroit, we found that, through the 2013 Urban Agriculture Ordinance, the city had moved to regulate and support burgeoning urban agriculture activity, which has been putting vacant land to use and bringing fresh food to many neighborhoods. It did this through an inclusive process involving the urban farming community as well as planning professionals, and negotiations with state-level farm interests overcame a major legislative barrier.

In the city region of the Golden Horseshoe around Toronto, Canada, we found a healthy alliance of people from across the food system implementing the ten-year Golden Horseshoe Food and Farming Plan to support the economic viability of the sector. How did they manage to agree on a common plan between many different actors, professions, and potentially conflicting interests? The key was a drawn-out drafting process with skilled mediators going back and forth to reach consensus-wording that meant the same to everyone.

In Belo Horizonte, we found a policy to tackle food insecurity that has been in place for more than 20 years. What lay behind the longevity of this policy was undoubtedly its early institutionalization within city government, while civil servants have worked behind the scenes to uphold the core principles, particularly through changes in municipal government.

In Amsterdam, we found a relatively new policy that promotes integrated working between city departments to address the structural causes of obesity. What enabled this integrated working was requiring each department to identify ways to address obesity through its day-to-day work. Moreover, to demonstrate that obesity is not just a public health matter, initial responsibility for the program was given not to the Public Health Department but to Social Development, instead.

Cities are doing a lot. They are identifying, leveraging, and growing their powers where necessary. They are engaging across government, involving communities, civil society, and food system actors, finding innovative ways to fund themselves and working hard to gain the political commitment needed for them to last. What we now need far more of is monitoring, evaluation, and learning. Cities are aiming to transform their food systems, no less. To do so, we need to know more about where they are having an impact, what the impact is, and what can be done better. A better understanding of the pathways to positive change will help show, even more, what urban food policy can do to change the food system and where it can have the most impact.

Click Here To View The Full Report

Urban Aquaponic Farmer and Chef Redefines Local Food in Orange County, CA

Urban Aquaponic Farmer and Chef Redefines Local Food in Orange County, CA

Heads of lettuce gain their sustenance through aquaponics channels at Future Foods Farms in Brea. Photo courtesy Barbie Wheatley/Future Foods Farms.

In a county named for its former abundance of orange groves, chef and farmer Adam Navidi is on the forefront of redefining local food and agriculture through his restaurant, farm, and catering business.

Navidi is executive chef of Oceans & Earth restaurant in Yorba Linda, runs Chef Adam Navidi Catering and operates Future Foods Farms in Brea, an organic aquaponic farm that comprises 25 acres and several greenhouses.

Navidi’s road to farming was shaped by one of his mentors, the late legendary chef Jean-Louis Palladin.

“Palladin said chefs would be known for their relationships with farmers,” Navidi says.

He still remembers his teacher’s words, and now as a farmer himself, supplies produce and other ingredients to a variety of clients as well as his restaurant and catering company.

Navidi’s journey toward aquaponics began when he was at the pinnacle of his catering business, serving multi-course meals to discerning diners in Orange County. Their high standards for food matched his own.

“My clients wanted the best produce they could get,” he says. “They didn’t want lettuce that came in a box.”

So after experimenting with growing lettuce in his backyard, he ventured into hydroponics. Later, he learned of aquaponics. Now, aquaponics is one of the primary ways Navidi grows food. As part of this system he raises Tilapia, which is served at his restaurant and by his catering enterprise.

Just like aquaponics helps farmers in cold-weather climes grow their produce year-round, the reverse is true for growers in arid, hot and drought-prone southern California.

“Nobody grows lettuce in the summer when it’s 110 degrees,” Navidi says.

But thanks to aquaponics, Navidi does.

Navidi also puts other growing methods to use at Future Foods Farms. He grows San Marzano tomatoes in a greenhouse bed containing volcanic rock (this premier variety was first grown in volcanic soil near Mount Vesuvius in Italy). Additionally, he utilizes vertical growing methods.

For Navidi, nutrient density is paramount—to this end, he takes a scientific approach in measuring the nutrition content of his produce. In the past, he and his staff used a refractometer, but now rely on a more precise tool—a Raman spectrometer. This instrument uses a laser that interacts with molecules, identifying nutritional value on a molecular level.

With a Raman spectrometer, Navidi measured the sugar content of three tomatoes—one from a grocery store, one from a high-end market, and one that he grew aquaponically. Respectively, measurements read 2.5, 4.0 and 8.5.

Navidi wants his customers to know about these nutritional differences, so he educates his Oceans & Earth diners through its menu and website. Future Foods Farms also offers internship opportunities to students from California State University, Fullerton. Interns conduct research and learn about cutting-edge ways to grow food.

Navidi believes aquaponics and other innovative growing methods can lead to a more robust local food system in Orange County. But he also sees some of southern California’s undervalued resources—namely, common weeds such as dandelion and wild mustard—helping the region become a major local foods player.

“We need more research on nutrients in weeds,” he says. “Dandelions and mustard are power weeds, and need little water.”

While these wild plants are important, they’re no substitute for policy. Navidi would like to see farmers in the county pay lower rates for water, and believes that a revised zoning code is needed for a county that is urban and becoming more so.

“Now, urban farming is happening all over,” he says. “We need changes to our zoning laws—politicians realize that.”

New zoning rules could help others in Orange County venture into aquaponics, something Navidi feels is necessary not only for the county, but for the country.

“For America to be sustainable, it needs aquaponics,” he says.

Ultimately, Navidi’s goal is to provide the best product possible, with an eye toward simplicity, health and wholesomeness.

“Any fine-dining chef is concerned with the quality of their product,” he says. “There’s nothing better than real food. I try to grow the most nutrient-dense tomato possible. Just add sea salt and black pepper—that’s all you need.”

Convention Center Plays Host To Urban Farm: Take A Look Around

Convention Center Plays Host To Urban Farm: Take A Look Around

2017

Tour the urban farm outside Cleveland's convention center

BY EMILY BAMFORTH, CLEVELAND.COM | ebamforth@cleveland.com

CLEVELAND, Ohio -- Look out of some of the windows of the Cleveland Convention Center, and you'll see greenery, dozens of chickens, lines of bee hives and three pigs.

It's a sight that brings Clevelanders on their lunch breaks or enjoying downtown during the summer months peering over the top of the building from the mall above, trying to sneak a peek at the animals below.

The farm is run by, and produces significant amounts of ingredients for, Levy Restaurants, the food service provider for the convention center. The project began more than three years ago with beehives, and has slowly grown to include raised beds, chickens and pigs.

Read more: Honeybees bring the sweetness of urban agriculture to Cleveland's convention center

The farm is part of the convention center's sustainability efforts. More than 50 percent of the trash from the the Global Center for Health Innovation and the convention center was recycled in 2016, according to a report by SMG, a firm hired by the Cuyahoga County Convention Facilities Development Corporation to manage operations for the facilities.

The three Mangalista heritage breed pigs help with the recycling efforts by eating some of the food scraps.

Find out more about the farm and sustainability efforts at the convention center in the video above.

Some Urban Farmers Are Going Vertical

In a factory parking lot in Brooklyn, a crowd of about 100 people gasped and murmured as Tobias Peggs cracked open the heavy metal doors of a white shipping container, allowing pink light to spill out from within.

Some Urban Farmers Are Going Vertical

2017

In a factory parking lot in Brooklyn, a crowd of about 100 people gasped and murmured as Tobias Peggs cracked open the heavy metal doors of a white shipping container, allowing pink light to spill out from within. The interior of the container looked like a dance club, or a space station: Strips of dangling LED lights glowed red and blue, illuminating white plastic panels. Leafy green vegetables grew from the walls.

Mr. Peggs, 45 years old, chief executive of a new company called Square Roots, recently was leading a farm tour of his new urban agriculture operation in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn. The shipping container was a vertical farm, one of the company’s 10 located in the parking lot, each capable of growing the equivalent of 2 acres of crops in a carefully controlled indoor environment, he said. Square Roots, which uses hydroponic technology to raise a variety of herbs and greens, is one of the latest companies to join the expanding industry of high-tech indoor farming. Proponents of vertical farming say it is designed to meet the increasing demand for locally grown food—fueled by distrust of large-scale industrial agriculture—at a time when more people are moving into cities.

Square Roots, co-founded by Kimbal Musk, brother of famed inventor and businessman Elon Musk, isn’t only growing vegetables. The company is trying to cultivate a network of food entrepreneurs by operating a kind of apprenticeship program. Each of its 10 shipping-container farms is run by a different entrepreneur selected from hundreds of applicants.

Messrs. Musk and Peggs have a grand vision: A network of Square Roots farms in urban centers across the U.S., each supplying locally grown produce to city-dwellers, while transforming mostly young people into urban farmers and food entrepreneurs. While there is no age limit, the farmers in the first group range from 22 to 30 years old, Mr. Peggs said. Growing vegetables inside windowless metal boxes, however, has its difficulties. Critics of vertical farming point to extreme energy use, high price points of the final product, and the limited selection of vegetables that can be grown this way. Mr. Peggs acknowledges these challenges but says they can be overcome with rapidly improving technology. LED lights are quickly becoming more efficient, for instance, and the addition of solar panels could take the containers entirely off the grid in coming years, he noted.

Square Roots started last summer with $3.4 million raised from a first round of investors, Mr. Peggs, said. The company spent more than $1 million building the farm—buying and setting up 10 shipping containers from a Boston company called Freight Farms for more than $80,000 each. Farming began in November. Each entrepreneur selected was required to invest several thousand dollars in his or her farm, refundable at the end of the year, Mr. Peggs said. Nine of the farmers received microloans from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The new farmers took an eight-week course, learning how to cultivate hydroponic crops, and then decided what vegetables to grow and how to sell them. The farmers soon began cultivating crops such as watercress, basil, lettuces, Swiss chard, bok choy, and cilantro.

Square Roots plans to make money through a revenue-sharing model, taking a cut of whatever income the 10 farmers generate. Along the way, each entrepreneur is given mentoring and guidance on farming, as well as branding and marketing, Mr. Peggs said. The company is generating revenue, but is deliberately not running at a profit, to establish the platform, he said. Mr. Peggs declined to detail the profit share with farmers.

One of the farmers, Erik Groszyk, said recently that he had only just started making money from his farm. He raises arugula, mustard greens, and tatsoi, fueled by a $12,000 microloan from the USDA. He said he sells his produce directly to restaurants and is part of a companywide sales program called Farm-To-Local, a subscription service that delivers bagged greens to office workers at their desks around New York City.

Packets of salad greens—about the size of a bag of chips—cost between $5 and $7. At that price point—higher than New Yorkers might find at their supermarket—Square Roots won’t achieve its goal of making fresh local food accessible to everyone. But Mr. Peggs is quick to point out that Starbucks sells millions of coffee drinks a day at a similar cost. Neil Mattson, a professor of plant science at Cornell University, notes there are other drawbacks to shipping-container farms, such as a carbon footprint two to three times greater than a greenhouse because of the large amount of electricity required to run the lighting and ventilation systems.

Mr. Peggs said each shipping container costs about $1,500 per month to operate, with electricity and rent as the biggest expenses at about $600 each. Transportation costs are low because most deliveries are made by bike or subway. Mr. Mattson said greenhouses, which offer the same control of growing conditions as a vertical farm and can include LEDs to supplement sunlight, are often a better option for producing crops in or near urban areas. Mr. Peggs, however, contends that shipping-container farms are still the best option for Square Roots, which is less interested in scaling up to large operations that can replace industrial farms, and more interested in cultivating many farmers working smaller operations, so everyone knows their grower and where their foods comes from.

Going Green - How Worcester, Central Mass Are Leading The Way

Solar Farm panels on the former Greenwood Street Landfill. Elizabeth Brooks photo.

The irony seeps through the ground – a vast wasteland on Greenwood Street that once held heaps of residential trash for more than a decade is now home to what city officials deem to be the largest municipally-owned solar farm in New England. With a ribbon-cutting ceremony expected to occur sometime this summer, the 25-acre site will have completed its transformation from an environmentally unfriendly dump to one that will be the greenest of the green in terms of energy saving measures.

The solar arrays over on the south side of Route 146 are impressive – 28,600 panels tilted at 25-degree angles, row after row, one after another. And then, just up ahead, with the hills in the distance on the northern side of 146, a lofty wind turbine spins at 262 feet high on the campus of Holy Name Central Catholic Junior/Senior High School. Separately, the two are just some of the many energy efficiency projects in the city; together, they serve as a beacon along the highway, a gateway to the city and the road map for the future. Driving down the highway and seeing both gives a feeling of “Welcome to Worcester,” says John Odell, Energy & Asset Management director for the city.

Welcome to Worcester, indeed. In a world of “going green,” the city has gone green enough that officials there consider Worcester to be a leader in such efforts.

“Yes,” says City Manager Edward M. Augustus Jr. “You might expect me to say that. I think you can prove that.”

In fact, “going green” is not a new concept for Worcester. Efforts date back to before the current administration, and other city institutions, such as Worcester Polytechnic Institute, have been practicing energy efficiency for more than a decade. Worcester was one of the first in the state to have a curbside recycling program and a climate plan, and it was also one of the first certified Green Communities. Even the Beaver Brook Farmers’ Market, which sets up Mondays and Fridays on Chandler Street, is the oldest in Worcester – its roots dating back to the ‘90s, when it was originally located near City Hall.

Even so, “It’s easy not to notice the strides the city has made in green issues,” says Steve Fischer, executive director of the Regional Environmental Council, an organization that started in 1972 with a mission to study clean air, clean water and open space issues. It has since expanded over the years to include other green initiatives, including urban farming.

Today, however, officials want residents to take note of Worcester’s many green efforts.

Saint Gobain Kiln.

Worcester Energy, a municipal initiative of the Executive Office of Economic Development and the Division of Energy & Asset Management, has an extensive website detailing the city’s green projects past and present. And both Augustus and Odell cited three ongoing projects – not only the solar farm, but also a street light replacement conversion and an energy aggregate plan – that have had or will have significant impact on the city. The three together, Odell says, are “near completion or far enough along that we can say we are in a leadership position. We’re in a great position to start spreading the word.”

Ten years ago, the city entered into a multiyear, multi-million energy efficiency and renewable energy project to assess all of its municipal facilities. Honeywell International was hired in 2009 as Worcester’s Energy Services Company to conduct energy audits of those buildings. Two years later, the city signed an Energy Savings Performance Contract for $26.6 million. As part of the ESPC, energy conservation work was to be done in 92 of the city’s largest facilities, out of 171 total. Some buildings have benefited from small changes, such as computer power management systems, while other, more aging facilities have received more extensive improvements – heating and cooling systems, insulation, air-sealing, lighting fixtures and water conservation equipment and solar panels.

The goal, according to Odell, was to save $1.3 million a year – an amount guaranteed by the ESCO. But a recently completed assessment of the ESPC revealed a $1.7-million savings per year.

“Energy efficiency has become a really good investment,” Odell says. “I think it’s important to note that the dollars are real. It costs money to do these things, but because of the benefits you get, it’s a savings.”

Mayor Joe Petty agrees, saying green energy is ever-important, not just for the environmental aspects, but for cost-savings as well.

“I know it’s a little more expensive sometimes, but that in itself is a positive,” he says, adding the city’s endeavors are going to save millions of dollars over the next several years.

A major contributor to those savings are the city’s numerous solar projects, including the Greenwood Street solar array. Although it cost approximately $28 million to construct, with a three-year payback, the 8.1-megawatt farm will produce about 10 million kilowatt hours of electricity each year once connected to National Grid’s distribution center. That’s enough to offset the electricity used by more than 1,300 homes in the city. In total, the city expects a return of about $50 million over the 20 years of the project, plus approximately $15 million more the following 10 years.

“It’s equivalent to 19 football fields of energy,” Augustus says. “That’s a big deal in terms of taxpayers’ dollars and in terms of shrinking our carbon footprint.”

Another major project completed this past fiscal year involved the installation of approximately 4,500 LED, high-efficiency street lights throughout the city, a measure expected to save $400,000 in electricity costs. Once all 14,000 planned street lights are switched over, city officials say they expect the savings to be more than $900,000 per year.

Beyond the cost savings are the additional benefits that come with the new street lights. Officials say the lights will cost less to maintain and have longer life cycles, reduce carbon emissions and light pollution at night, and improve lighting quality overall, plus give a sense of greater security. According to Augustus, Los Angeles County did a similar street light conversion and officials there credited the project with a 10-percent reduction in crime because the intensity of the lights was able to be calibrated at specified times.

“There are a lot of operational efficiencies that come from having this kind of technology,” Augustus says.

In addition to those projects, Worcester has upgraded lighting at four parking garages to LED, saving an additional $89,000 per year in electricity costs; completed a $1.7 million lighting upgrade project at the DCU Centre without using any taxpayer funds; and replaced a failing HVAC center at the senior center, among other initiatives, with more on the way. And when President Donald Trump announced the federal government would no longer participate in the Paris Climate Agreement, Petty made his own announcement: that the city would continue to battle climate change locally and invest in green technology.

“As our federal government retreats from its responsibility as steward of our environment, it is vitally important for state and municipal government to uphold our commitment to the future of our planet,” says Petty, who joined mayors across the country in signing the U.S. Climate Mayors statement. “If the president doesn’t want to do it, we will.”

Mary O’neill and Eva Elton display fresh produce at the Mobile Farmers Market Laurel St. location, in Plumley Village.

Green Schooled

Worcester Public Schools has gotten into the green zone as well. Over at 35 Nelson Place, a school dating back to 1927 is being demolished in preparation for a new building to serve Worcester students in pre-kindergarten through grade 6 starting this fall. But unlike the old Nelson Place School, the new 600-student facility will be twice the size – 110,000 square feet compared to the original’s 55,000 square feet – and will be the city’s first-ever, net-zero energy building, defined by the U.S. Department of Energy as, “an energy-efficient building where, on a source energy basis, the actual annual delivered energy is less than or equal to the on-site renewable exported energy.”

And even though “you could effectively pull that building off the grid,” Odell says, that doesn’t mean the new school is being built with highly-specialized technology and equipment. On the contrary, it’s all “off-the-shelf technology.”

According to Brian Allen, chief financial and operations officer for Worcester Public Schools, the roof’s solar panels will provide 100 percent of the building’s energy, and together with the high-efficiency windows and insulation, “natural gas for heating will be one-third of what we’re using.”

“You basically have one school taking care of itself,” Augustus says. “Imagine if I could have every city building take care of itself.” The school was designed as a green building from the start as part of the application process for the Massachusetts School Building Authority, which works with cities and town across the state to help build affordable, sustainable and energy-efficient schools. Because the state offers more reimbursement credits for green buildings, it made more sense to create the new Nelson Place School as net-zero energy, Allen explains.

The new Nelson Place School is just one of the many examples of how the city of Worcester and the educational system have collaborated on the ESCO contract, and in the near future, the hope is to do another energy partnership with the schools, Augustus says. Many of the schools have benefited from new doors and windows, with others slated for similar work soon.

“The city,” he says, “has been very aggressive over the years with window replacement, making them energy-efficient and more aesthetically pleasing in some of the older buildings.”

Other schools have been outfitted with new boilers and exterior LED lights, while converting interior lights is currently being explored, according to Allen. In addition, the school district as a whole also benefits from numerous solar panels at its buildings, about 3 million kilowatts of energy, Allen says. Two of the schools have parking lot canopies, and eight – including the new Nelson Place – have roof arrays. Four of those roofs, according to Odell, were nearing the end of their lifespan and were resealed with white roof coating application instead of black to make the arrays more effective.

“The net effect,” said Odell, “is we got the roofs for free.”

As a result, all of these green efforts are beneficial to the city and school district and the students. “Any way that we can be part of the initiatives and save money and be more environmentally aware, it seems to perfectly align with the mission of the school district,” Allen says, noting it also demonstrates to students that there are ways to be environmentally conscious and friendly.

The solar panels on the roof of the new Nelson Place School

Windfall

Holy Name’s wind turbine is another example of how the city has collaborated with schools. Although it is a private school and no city funds were expended to construct the turbine, regulations did not allow for such projects a decade ago. City officials, however, allocated staff resources to review the regulations, and as a result, in June 2007, adopted the Large Wind (Energy Conversion Facilities) Ordinance, allowing for wind turbines to be located in Worcester by special permit with provisions for height, abutting uses buffers and noise regulations.

The turbine has been largely successful. Holy Name, built in 1967 and heated electrically, was paying $180,000 in utility bills each year, according to a sustainability profile by Worcester Energy. In 2015, when the report was written, the turbine was producing an average of 74 percent of Holy Name’s yearly energy needs.

That’s one of the reasons why Worcester officials feel it is so important to partner with other schools and businesses on green technology.

“It allows us to be credible,” when businesses want to locate or relocate in the city, so that they don’t feel like they’re working on projects in isolation, says Odell.

City officials also believe it is important to help residents go green – and stay green. The Municipal Electric Aggregation program, which City Council recently approved, pools all of Worcester’s National Grid customers into one negotiating block as long as they are signed up for the Smart Grid program. By doing so, the city can offer residents and businesses various components of green energy to them.

“That’s the next big thing,” Odell says. “You can make your own portfolio greener.”

Saint Green

One such company that is no stranger to green issues is Saint-Gobain, a world leader in designing and building high-performance, innovative and sustainable building materials. Recently, the company announced a renewed commitment to the U.S. Department of Energy’s Better Plants Program, which works with manufacturers to improve energy efficiency to drive cost savings for the industrial sector. Eighty four of Saint-Gobain’s manufacturing plants in the country – Worcester included – are participating in the program, with a goal of achieving an energy savings of 20 percent over the next 10 years. Saint-Gobain joined the program in 2011, the same year it launched.

Michael Barnes, vice president of operations for Saint-Gobain Abrasives North America, says the company chose to focus on the Better Plants Program because it “really aligns with our own strategic direction. Saint-Gobain is committed to not only what we do every day with the products we make and sell, but in the communities as well.”

In Worcester, specifically, the plant is getting a lights makeover with the installation of LED lamps, plus a new kiln was installed. Many of the company’s products, Barnes says, are fired in high-temperature kilns, and the new one has provided the company with a significant reduction in natural gas consumption. In addition, Saint-Gobain in Worcester has its own powerhouse that generates steam, which in turn heats the buildings, so that the company not only procures energy but produces it as well.

It’s a “very smart move,” Barnes says, to look at the energy the company consumes and expels. Part of that as well is the company’s carbon monoxide emissions, which SaintGobain seeks to reduce by 20 percent.

With these strategic, long-term plans “heavily supported” by capital investment, a creative team and the continued financial support from the corporation, Barnes says, it shows Saint-Gobain’s commitment to remain in Worcester and to contribute to the city’s employment rate.

“It’s difficult to do business in New England. It’s a high-cost area. It’s very highly regulated environmentally. It’s easy for people to say, ‘Let’s do this elsewhere,’” Barnes says.

But, he adds, the company remains committed to its Worcester roots and helping the environment as well through its Better Plants Program participation.

“Energy is a very critical cost component. That’s why we take this initiative seriously,” he says, adding, “This isn’t just something we talk about. It’s something we’re committed to.”

While the company cites its efforts to become more environmentally friendly, it has not been without its missteps. Saint Gobain allegedly violated the Clean Water Act, reaching a settlement last December with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that required the company to pay a $131,000 penalty and to install new storm water treatment equipment.

Technically Green

If Worcester and its businesses have been in the green game for some time, WPI has, too. In fact, its very mission statement pledges the college will “demonstrate our commitment to the preservation of the planet and all its life through the incorporation of the principles of sustainability throughout the institution.”

WPI has a Sustainability Plan, an initiative put into motion during spring 2012 by the WPI Task Force on Sustainability, that outlines goals, objectives and tasks for academics, campus operations, research and scholarship, and community engagement. It offers 119 undergraduate and 30 graduate sustainability related courses, as well as a minor degree in sustainability engineering. And, back in 2004, five undergraduate students from the college were the ones to conduct the wind turbine study at Holy Name’s request.

Ten years ago, the Board of Trustees passed a resolution that all new buildings be designed to meet LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification, a national rating system created by the U.S. Green Building Council. Today, WPI boasts four LEED buildings: Bartlett Center, LEED Certified in 2006; East Hall, LEED Gold in 2008; the Recreation Center, LEED Gold in 2012; and Faraday Hall, LEED Silver in 2013.

Although WPI has many sustainability programs, two have stood out, according to WPI Director of Sustainability John Orr, who is also a professor emeritus of electrical and computer engineering.

“The project with the greatest environmental impact has been our building energy and lighting retrofit program that saves energy and reduces greenhouse gas emissions,” Orr says. “This is largely invisible to the community, but has a great environmental impact. Our bike share program, Gompei’s Gears, is highly visible and has received great community feedback.”

Gompei’s Gears was originally an Interactive Qualifying Project (submitted for degree requirements) by two students, Kevin Ackerman and John Colfer, and the program has evolved from an idea in 2015 into a fullscale program. Gompei’s Gears, named after the WPI mascot, allows students, faculty and staff access to bikes from various locations on campus that they can ride anywhere on site or even off school grounds. It is available after spring break (weather depending) until the first snowfall.

For all its efforts, in June WPI earned a gold rating in the Sustainability, Tracking, Assessment and Rating System (STARS), awarded by the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education. Two years ago, the first time the school submitted a STARS application, it earned a silver rating and worked hard to improve upon that. This year, WPI was one of 117 schools out of 415 total that received a gold rating. Only one received platinum, 201 silver, 67 bronze and 29 reporter rating.

Orr says he believes the campus’ four LEED-certified buildings – with another under construction – Gompei’s Gears, the building energy upgrades and other programs make WPI a leader in the “going green” movement out of colleges in similar size.

“Also, very much in our educational programs – environmental engineering and environmental and sustainability studies – and our global project programs in developing nations,” Orr says. “Advanced technology is required to address the world’s environmental challenges, and we are showing leadership in our campus operations, our educational programs and our research (advanced batteries, biomass, advanced recycling, etc.).”

Leeding and Leading the Way

Other Worcester and Central Mass colleges are making an effort to go green as well.

At Assumption College, the new Tsotsis Family Academic Center, which will open this fall, and site lighting were all designed for LED lights, with the exception of specialized lighting in the performance hall, according to the school’s Office of Communications. Five interior space renovations are underway, where the lighting will be replaced with LEDs and reverse refrigerant systems will be installed in place of air-conditioning to control the temperature within those particular spaces. In addition, speed controllers were added to the HVAC units in the Fuller/IT buildings, and last summer, low flow shower heads and aerators were installed on the sink’s faucets in all the resident halls. Opened in 2015, it is the first building on the campus to be designated LEED certified and is the only Gold-certified building in southern Worcester County (a term sometimes used to define towns south, southwest and southeast of Worcester), according to college officials.

Over at Nichols College in Dudley, its newest academic building was awarded LEED Gold certification last year. Opened in 2015, it is the first building on the campus to be designated LEED certified and is the only Gold-certified building in southern Worcester County, according to college officials. The three-story building’s green components include locally-sourced and recycled materials; excellent indoor air quality; efficient water use systems; sensors that better control heating and lighting in individual rooms; and large windows for natural light, which reduces the need for interior lighting and minimizes the use of electricity during the daytime.

“Gold LEED certification for the new academic building is an exciting accomplishment and a statement to Nichols College’s commitment to environmental stewardship,” says Robert LaVigne, associate vice president for facilities management at Nichols. “Since opening its doors last fall, the building has served as a testament to the college’s dedication to innovation – not only in sustainable design, but also education.”

Other green programs at Nichols include its single-stream, campus-wide recycling program, food waste recycling at Lombard Dining Hall, geothermal heating and cooling systems at two residence halls and LED conversion of all exterior lights on campus. In addition, Fels Student Center received National Grid’s Advance Building Certification for energy efficiency.

Food for Thought

But “going green” doesn’t just refer to eco-friendly buildings, energy-efficient lights and solar panels – it can also mean the food we eat and how it is sourced. In cities, people don’t always have access to fresh food, but Worcester has been working to change that as well.

On Mondays and Fridays, from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. at 306 Chandler St., the Beaver Brook Farmers’ Market sets up shop with local produce, plus bread and craft vendors. Originally the Worcester Hill Market, it is the oldest farmers’ market in the city, according to Fischer. It moved to Chandler Street when the front of City Hall closed for repairs, and the REC took over management in 2012.

Beaver Brook is just one of the city markets, which all opened in late June and run through Oct. 28. The University Park Farm Stand, a Main South staple since 2008, moved to its current location last year so that the REC could more closely partner with Clark University, the Main South Community Development Corporation and other area organizations to provide not only fresh food but family-friendly activities as well. It is open every Saturday, from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m., at 965 Main St. The REC also runs the Mobile Farmers’ Market, which makes 16 stops around the city Tuesdays through Fridays, bringing locally grown produce straight to residents who might not otherwise be able to travel to a farm stand. Fischer notes the city is home to many other farmers’ markets not run by the REC. “We’re seeing a demand in farmers’ markets,” he says. “We’re seeing a demand for local food.” Martha Assefa, manager of the Worcester Food Policy Council, agrees.

“There are so many amazing farmers’ markets happening in the city,” she says, recalling, “A while ago, it was a few folks at the table talking about this. Now local food and food access is becoming mainstream. I think folks are much more interested in buying local than they were 15 years ago.”

But is buying fresh and local more expensive? The Healthy Incentives Program makes sure people who receive SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) assistance have just as much access to fresh food as others. Through March 31, 2020, the program will match any SNAP dollars spent at farmers’ markets or stands, mobile markets and Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) farm stand programs. Families of one to two people can have up to $40 instantly debited back to their EBT card each month, $60 for three to five people, and $80 for families with six or more people.

“I think many folks realize it makes sense to buy local,” Assefa says, adding it reduces the amount of food travel from producer to consumer, and it also reduces some of the packaging it comes in as well. Plus, it directly helps local farmers – and all that leads to a greener planet.

“A lot of the farming community knows how important it is to protect Mother Earth. A lot of the farmers are innovators. If they don’t protect it, they’re going to see it on their fields,” Assefa says. “That’s the forefront of it all,” she says. “Plus, local food tastes better.”

Urban Gardens

Just as farmers’ markets are not reserved for the suburbs, neither are gardens. In 1995, the REC started a network of urban farms and community gardens that has now grown to 64 in number. These farms have allowed citizens to contribute to the community, learn about growing their own food and beautify their neighborhoods. There are also 20 gardens at the public schools, as well as a youth program in Belmont Hill for ages 14 through 18 that has been in existence since 2003, Fischer says. Both programs, he says, are “transformative,” adding that, for many, this exposure to gardening is the first time students see “how a carrot comes to be, how lettuce comes to be, other than buying it in stores.”

And by working in the gardens, Fischer continues, “They can see the fruits of their labor. It has an amazing impact.”

That’s precisely why groups in the city are pushing for more urban farming – specifically to allow residents to grow and sell their own food. Although personal gardens are allowed, Fischer says, residents are not currently permitted to set up roadside stands or sell to farmers’ markets or stores.

The Urban Agriculture Zoning Ordinance seeks to change that.

“It’s a set of rules to make sure there are rules in place for growing and selling food in the city,” Fischer says. “Right now there’s a big hole in the regulations for growing food in the city.”

Currently in committee hearings, the ordinance has been three years in the making, after the mayor convened a working group with concerned citizens, those associated with urban farming, the Chamber of Commerce and other groups to look at the zoning regulations from environmental and social justice perspectives, Fischer says.

The Worcester Food Policy Council is also heavily involved with the proposal to make sure anyone in the city can farm their land and in turn sell their products. The ordinance has received some pushback, however, particularly among area beekeepers who worry it will infringe upon their efforts.

The ordinance would require beekeepers to notify abutters that they have bees, which the keepers find potentially prohibitive. Worcester Magazine wrote about their concerns earlier this month, in a story titled, “Beekeepers buzzing over proposed urban agriculture ordinance.”

Still, says Fischer, the ordinance and other work is an acknowledgment that urban agriculture is real.

“There is a growing interest as to how the food is produced and where it is grown and the quality of how it’s grown,” he says, noting that “it’s full circle, and essentially we need to rebuild the infrastructure that was dismantled over the last decade, and also to rebuild the biodiversity.”

Plus, says Fischer, “It’s exciting to have the city and local businesses and the residents taking an interest in these things and providing leadership in moving things forward.”

It is a project of which the mayor is particularly proud.

“I think it’s a great asset to the city,” Petty says of the ordinance. “We are taking what people are doing anyway and putting some rows around it.”

Plus, he adds, with that and the existing farmers’ markets, “It’s a driver for jobs. We’re taking locally grown food and selling it.”

Barking Up a New Tree

Amanda Barker knows much about urban agriculture. On a sunny day, she is planting scallions at Cotyledon Farm, her newest venture in nearby Leicester. She is the founder of Nuestro Huerto on Southgate Street in Worcester, which she watched grow from a small-scale community garden to a successful urban farm.

When she moved to Main South eight years ago for graduate school at Clark University, she didn’t know anyone but had a desire to “ultimately help create and become part of a community around food,” she recalls.

Barker started a garden in her back yard, but soon found the shady space and the lead in the soil made it unsuitable for growing anything. Faced with needing to take on an unpaid internship for her requirements at Clark, her “practical” gardening project ended up becoming long-term when she set up on land owned by Iglesia Casa de Oración (House of Prayer Church). Initially, she says, she started with 10 raised wooden garden beds, with the intent to give away the food for free. Eventually, it became a full-scale urban CSA.

“It demonstrated interest and demand for those projects. Certainly, we weren’t lacking for volunteers, depending on the day,” Barker says, recalling that there were always a “lot of young people showing interest in being outside and being in a non-city place. It was a respite and a green space.”

Today, after a largely successful run, Nuestro Huerto and the CSA are now closed to the public, but with good reason—the site is host to three farmers from Nepal who will use the opportunity to provide for themselves, their families and their communities. Barker still serves as a liaison for the project, she says, even though the farmers are mostly independent.

“You can produce incredible amounts of food, and they certainly are. Every inch is going to be packed with vegetables,” she says.

It is why she has “mixed thoughts” on the Urban Agriculture Zoning Ordinance.

“What I want is everything to be allowed by right in all zones,” Barker says. “We’re human beings; we eat food. What is there to have a conversation about?”

If the proposal is successful, it should address some of her questions and transform some of those blank spaces into only more green spaces for the city.

“We’re excited about the potential urban agriculture has in responding to how difficult it is for some people who are working hard but are unable to access fresh food,” Fischer says. “It also makes neighborhoods beautiful. That is a key strategy for beautifying the city.”

Not only that, but “people in the area grow to love those neighborhood farms, and they look out for it,” he says. Between the urban farms and solar farms, plus all the energy-efficiency programs, is there room for Worcester to improve? Augustus says,“Yes,” adding Worcester should “continue to set the pace of what can be done by a municipality … in terms of great and innovative ways to save the taxpayer money instead of being paid to a utility to produce.”

Worcester, Petty says, “is killing it” not only with green issues, but other aspects as well, such as the arts.

“I think we have a government that’s pretty interactive, and people are noticing. We’ve made all the right decisions so far.” When it comes to going green, he says, “This is good, cooperative effort between the government and the community.”

The 'ekofarmer' by Exsilio Is A Pop-Up Urban Farm For City Streets

Wouldn’t it be great if you could have fresh, locally grown produce, from the comfort of a city? it’s no surprise that urban farming has become popular in recent years, with city slickers attempting to grow fruits and vegetables in backyard gardens, on rooftops, or even indoors using hydroponic systems.

The 'ekofarmer' by Exsilio Is A Pop-Up Urban Farm For City Streets

Wouldn’t it be great if you could have fresh, locally grown produce, from the comfort of a city? it’s no surprise that urban farming has become popular in recent years, with city slickers attempting to grow fruits and vegetables in backyard gardens, on rooftops, or even indoors using hydroponic systems. while all of these solutions are only possible on a small scale, finnish start up exsilio oy is making urban farming possible for whole cities with their modular pop-up farms. just as pop-up shops or cafes, the ekofarmer pod be easily set up in the middle of town, sprouting cost effective crops to grow fresh food for everyone.

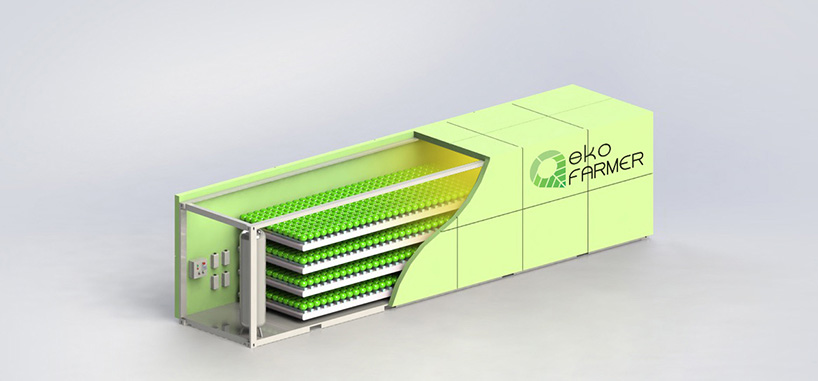

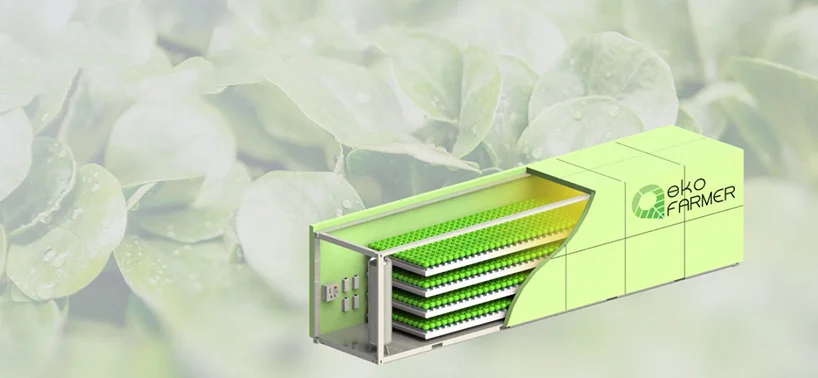

images courtesy of exsilio oy

branded as a ‘resource-efficient urban farming chamber,’ the ekofarmer combines high-tech solutions with the easiness and safety of locally produced healthy and clean ecological food. the 13-meter long module forms a closed ecosystem, which needs only electricity and water to function. the levels of humidity, water and carbon dioxide inside can be adjusted to produce optimum yield and the best possible flavor. the neat little module is carbon-neutral, transferable, and can be placed almost anywhere without taking up a whole lot of space.

the shipping container-shaped chamber enables restaurants, businesses owners and small-scale farmers to use efficient and profitable urban farming methods. exsilio oy estimate each module can produce approximately 55,000 pots of salad per year–around 3 times more than the amount that could be produced in a greenhouse, since cultivated plants are located on multiple floors within the farm.

farmers can use the module to grow their own choice of herbs, salads, seedlings, and even non-food plants. ‘our solution is ideal for example for restaurants and institutional kitchens wanting to produce their own ingredients,’ explains Thomas Tapio, CEO of exsilio. ‘the modules also serve as an excellent option for farmers to replace their traditional greenhouses.’

beatrice murray-nag I designboom jun 27, 2017

Urban Gleaning Grows Up

America’s 42 million home and community gardeners grow an estimated 11 billion pounds more food than they can use. Meanwhile, 87 percent of Americans are not eating enough fruits and vegetables.

Urban Gleaning Grows Up

From branch-sensing technology and drones to supporting refugees, the urban gleaning movement is ripe with innovation.

BY JORDAN FIGUEIREDO | Food Waste, Nutrition, Urban Agriculture | 07.12.17

America’s 42 million home and community gardeners grow an estimated 11 billion pounds more food than they can use. Meanwhile, 87 percent of Americans are not eating enough fruits and vegetables.

The good news is the movement of people who harvest that excess home-grown food, known as urban gleaning, has matured over the past decade or so from a weekend hobby for locavores to a growing sector of the food economy. In recent years, dozens of private and public groups around the U.S. have gotten organized around getting this extra food onto people’s tables.

At the recent Gleaning Symposium, hosted by the Green Urban Lunchbox in April in Salt Lake City, today’s urban gleaning renaissance was on full display. More than 10 organizations from places as far flung as Atlanta, Philadelphia, and Tucson spent two days sharing information, strategy, and stories about building the urban gleaning movement around the U.S.

Among the participants were volunteer computer scientists from Boulder, Colorado, who have created an online map that’s logged 1.2 million of the world’s edible (and gleanable) plants; a couple of guys from Atlanta who turned their old-fashioned southern music jamboree cider fest into a gleaning organization; and a Salt Lake City organization that transformed a 35-foot school bus into an educational greenhouse and gleaning organization. It was clear from these innovations and more that gleaning organizations have come a long way in recent years.

Taking Care of Trees, People, and More

We’ve long known that eaters benefit from urban gleaning, but it’s becoming increasingly clear that tree-owners do, too. “Before we can finish our pitch, [fruit tree owners] are already like, ‘just take it, take [the fruit] away,’” said Craig Durkin, co-founder and board member of Atlanta’s Concrete Jungle. “They are tired of the rotting fruit and flies that often arrive when a tree produces way more than they can handle.”

There is a similar story being told in Utah. “A lot of homes in Salt Lake City sit on quarter-acre lots and the city was built around this idea that you would grow your own food,” said Shawn Peterson, founder and executive director of the Green Urban Lunchbox.

Peterson finds that many Salt Lake City homeowners can’t pay for the services to maintain their trees. So, in addition to gleaning, his organization also offers pruning, pest control, and fertilization services for fruit trees after the harvest season is over. The group has serviced and gleaned fruit from 2,500 trees over the last few years, but Peterson estimates there are 47,000 more out there.

Some urban gleaning organizations, like Tucson’s Iskashitaa, go beyond fruit trees and provide other services to the community. Iskashitaa, named after the Ubuntu word for working cooperatively, helps the area’s refugee population from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. In addition to connecting refugees through gleaning, Iskashitaa teaches English literacy and offers other community resources. As Iskashitaa founder and executive director Barbara Eiswerth explained, their participants may be isolated in other arenas, “but food is the common denominator—it brings us together, it empowers them.”

Stepping Up Gleaning Technology

Technology is increasingly connecting urban gleaning organizations to their communities in diverse ways. For example, Salesforce supports nonprofits in tracking volunteer statistics, pounds gleaned, donor contact information, and more, free of charge, making it much easier to run an organized gleaning operation than ever before.

Concrete Jungle’s Durkin partnered with Georgia Tech University to create tree-tracking software called FoodParent, which they offer for free to the community. The FoodParent maps also keep track of the seasons in which trees in the 500-square mile Atlanta area are ripe and ready to glean.

Durkin has also tested tree-surveying drones, “branch bending” sensors that can tell when trees are heavy with ripe fruit, and a branch-affixed device that photographs the trees (and fruit) and tweets out the pictures.

While technology can play a great role in advancing urban gleaning, several users did share some warnings at this spring’s Symposium. For instance, while open-source mapping has worked well for Falling Fruit, the worldwide, online, open-source map of our edible urban landscapes, it did not provide the same result for the Philly Orchards Project: When a selfish forager decided he wanted all Philly’s fruit to himself, he deleted their entire map! Ethan Welty, co-founder of Falling Fruit, also cautioned against using Google Maps for everything, as the technology makes it “so easy to move data that there are a lot of messed-up maps out there.”

Re-Connecting to Real Food

In a world over-saturated with processed food, the Jamie Oliver quote, “Real food doesn’t haveingredients, real food is ingredients,” hits the right mark. For this reason, empowering under-resourced (and unaware) folks to pick their own food—rather than requiring a team of volunteer gleaners—is a big part of the equation. Because much of that soon-to-be-wasted fruit grows in others’ yards, questions about how to glean without trespassing are regular aspect of the movement.

“More than 50 percent of the population is living in urban areas—how can they play a role in how we feed ourselves?” Welty said. “[With gleaning] people can stay connected to where their food comes from.”

Robyn Mello, orchard director of the Philly Orchards Project, echoed that sentiment. “People just haven’t been told they can harvest these trees that are everywhere,” she said. With 1,100 trees planted over the last 10 years in 57 community public spaces, Philly Orchards bridges that gap, re-connecting the community to food growing all around them.

“My vision is that somewhere in the future we are no longer necessary—and we get people harvesting all these trees on their own,” Mello said.

Photos courtesy of Concrete Jungle.

Queen City Acres Makes A Go Of Urban Farming

Queen City Acres Makes A Go Of Urban Farming

Ethan Thompson at MetroRock SUZANNE PODHAIZE

Scrutinizing the house in front of me, I thought I must have the wrong address. Deep gray with bright orange and white accents and a kiddie pool in the pristine front yard, the place didn't look like it could be the urban farm I was looking for in Burlington's New North End. But then farmer Ethan Thompson, lean and bearded, rounded the corner. He was wearing a sage-colored shirt depicting a fist holding a spade and the words: "Resistance is growing."

And so is he. Thompson, 37, has a master's degree from the University of Vermont in community development and applied economics as well as a certificate in permaculture design from Yestermorrow Design/Build Schoolin Waitsfield. For years, he has been cultivating produce at two locations — this New North End backyard that belongs to some friends and his own home in the Old North End. He calls his enterprise Queen City Acres.

At first, the food was intended to feed his friends' family and his own. But last year, Thompson realized that it wasn't a viable hobby. "I was putting in a ton of time to manage the garden ... It was very weedy, and I didn't have the time to stay on top of it," he said. "It seemed like a dead end."

A Queen City Acres plot | SUZANNE PODHAIZER

Thompson was on the verge of quitting when he found a YouTube series on profitable urban farming. "I was sitting at the computer, and what popped up is this fellow who's making a living growing food in other people's backyards," he explained. "Seeing how other people had done it, I was finally able to envision how I might do it."

And so he founded Queen City Acres. Thompson expanded the main plot in the New North End to 4,000 square feet. Then, in the same neighborhood, a woman who had tended her garden for 30 years and wanted help offered him another, smaller plot.

Thompson grows several crops in his own yard, including pea and sunflower shoots and pink and gray oyster mushrooms. "People love [them]," he said. "I had no idea to what extent sales would be driven by mushrooms."

Thinking about how to find customers for his new business, Thompson realized that he'd need to get creative. "In the first year, I didn't feel like I could commit to even the smallest farmers market," he said. He wasn't sure he could reliably produce enough food, and he worried that his limited selection couldn't compete with bigger operations.

Therefore, Thompson opted for a pop-up market model. Every Thursday, he totes his food to MetroRock climbing center in Essex Junction and sells it in the lobby. On Friday, he does the same at Scout & Co. on North Avenue in Burlington, just around the corner from his home.

Why these locations? "I was relying on my closest community, which is the climbing community," said Thompson, who also works setting routes at MetroRock. And, he continued, "I wanted to connect to my next closest community, my neighbors."

Oyster mushrooms| SUZANNE PODHAIZER

Stopping by the local coffee shop for a few hours a week, he noted, was a better business proposition than delivering vegetables to people's homes or having them randomly swing by his place for a head of lettuce or pint of cherry tomatoes.

In February, Thompson began popping up at MetroRock with shoots to sell and a sign-up sheet for his farm stand community supported agriculture, or CSA, shares. Unlike shares he's received, he doesn't decide what to package up for people each week. Customers pay in the spring and receive that amount, plus a bonus percentage, as credit. Then they choose whatever they want from his selection, whenever they want it. "It's a totally flexible model," the farmer said.

Thompson wanted to avoid the problems he'd had participating in other CSAs. "I'd done CSAs for a number of years but stopped," he said. "I was getting more stuff than I could use and got stuff I wasn't interested in using."

In his research on this agricultural model nationwide, Thompson found that the average rate of retention for customers is only 50 percent. He guessed that other participants had issues similar to his. By giving his customers free choice, he hopes to keep them.

At first, Thompson said, his pop-ups were a little slow, especially the one at Scout & Co. "It rained the first eight Fridays I was out there, and there weren't many people walking around," he lamented. But his fortune changed when he began weekly posts on Front Porch Forum about what he was going to have on offer. "That seemed to make a huge difference," Thompson said.

On a recent Thursday at the MetroRock pickup, a steady trickle of people stopped by to check out the cartons of late-season strawberries, bags of mesclun mix and mustard greens, and piles of radishes and carrots. Thompson said that greens — which grow quickly and can be cut several times — are one of the mainstays of profitable urban farms, as are baby roots. Bulky items or veggies that have a longer growing season, such as potatoes, cabbages and corn, are best produced in more rural environments.

Christine Dong, who works at MetroRock's front desk, remarked that having Thompson pop up with veggies at the gym is a boon for climbers. "It's really beneficial — everyone here likes to eat local," she said. "I love having the seasonal produce ... the mushrooms, the greens."

Based on this year's success, Thompson hopes to expand his operation in 2018 by adding two more plots. And, he said, "I've got feelers out for some sort of indoor space for doing microgreens in the off-season, and for storage."

Cherry tomatoes SUZANNE PODHAIZER

For now, Thompson's main plot produces mostly baby greens such as mizuna, mesclun from High Mowing Organic Seeds and red Russian kale — another best seller. He also grows cherry tomatoes and a few unusual crops, such as Egyptian walking onions and shiso, a mint variety.

The friends who own the main plot have also allowed Thompson to build a simple wash station for cleaning and packing veggies and a walk-in cooler for storage, both critical to the operation. Without that infrastructure, he said, he wouldn't want to be a professional farmer.

The farmed plots, wash station and cooler have taken shape without changing the character of the neighborhoods in which he's farming. From the street, the houses appear typical. Only when you enter the backyards do you notice row after row of tiny greens poking through the soil, a pile of kale drying under fans below the wraparound porch and a helper packing up carrots for the market.

The biggest difference, Thompson surmised, is that folks in the surrounding houses — most of whom are his customers — as well as his climber friends at MetroRock, now know exactly where their food is coming from.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Food in the Hood"

Indoor Ag Means Safer Conditions For Farm Workers

“Farm workers will no longer have to work with the risk of pesticide drift,” says Sonia Lo, CEO of FreshBox Farms, the nation’s largest modular vertical farm.

Indoor Ag Means Safer Conditions For Farm Workers

Vertical farm CEO says growing greens without pesticides, herbicides and other harmful chemicals one of many pluses of this booming industry

One of the potential benefits of the booming indoor farming industry is safer working conditions for the people who grow and harvest our food.

“Farm workers will no longer have to work with the risk of pesticide drift,” says Sonia Lo, CEO of FreshBox Farms, the nation’s largest modular vertical farm.

California regulators continue to debate how to best protect farm workers from harmful pesticides and herbicides, but when it comes to food grown indoors, in digitally controlled locations, it’s a moot point.

FreshBox Farms, like other Digital Distributed Agriculture (DDA) operations, uses sustainable growing enclosures, no soil, very little water, a rigorously-tested nutrient mix and LED lighting to produce the freshest, cleanest, tastiest produce possible.

“No pesticides or other harmful chemicals are used, so that means a safer working environment,” says Lo. “Conventional growers try to control and contain the chemicals sprayed on fields, but the fact is, in many cases, those chemical can contaminate groundwater, and air, not to mention expose field workers to harmful substances.”