Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Indicators For Urban Agriculture In Toronto – A Scoping Analysis

Indicators For Urban Agriculture In Toronto – A Scoping Analysis

Strong leadership and support will aid the growth of urban agriculture across Toronto.

Authors: Rhonda Teitel-Payne, James Kuhns and Joe Nasr

Toronto Urban Growers

Dec 2016

Executive Summary

When Toronto Public Health (TPH) identified a considerable gap in Toronto- specific data on the impact of urban agriculture (UA), Toronto Urban Growers (TUG) was commissioned to engage Toronto-based practitioners and key informants on identifying the most relevant and measurable indicators of the health, social, economic, and ecological benefits of urban agriculture. The overall objective of the work was to develop indicators that a wide range of stakeholders could use to make the case for making land, resources and enabling policies available for urban agriculture.

The process started with a desk study of recent attempts to create indicators to measure urban agriculture in other jurisdictions. Indicator experts were interviewed to identify effective strategies and common pitfalls for developing indicators. The preliminary research informed the development of a set of draft indicators and measures, which were reviewed by Toronto-based practitioners in one-on-one interviews and a focus group. This feedback was used to further refine the indicators and measures and to develop data collection tools for each measure. A subset of the practitioner group gave additional feedback on the feasibility of the data collection tools, leading to a list of 15 indicators and 30 measures recommended for use. The review also identified additional indicators for further development beyond the scope of the current project and a short list of indicators not recommended for use.

The diversity of urban agriculture was flagged as a complicating factor in developing widely applicable indicators, as UA initiatives vary according to type of organizational structure, focus of activities, size and capacity to collect data. Specific indicators such as improved mental health and social cohesion are difficult to assess, while even a seemingly straightforward statistic such as the amount of food grown is challenging to quantify and aggregate. This report also identifies key audiences for the indicators and how they might be used. For governmental audiences, rigorous data that emphasizes both the importance of UA to constituents and the capacity of UA to help achieve the goals and objectives

of specific government initiatives is crucial. Valid indicator data is equally valuable to engage private and institutional landholders and to increase public support among residents and consumers.

The report concludes by remarking on the need for partnerships between the City of Toronto and urban agriculture practitioners to start using the recommended indicators to collect data for the 2017 season and to simultaneously continue working on the more complex indicators to create a complete suite of tools. While individual organizations and businesses can collect data for their own funding and land use proposals, support for broader-impact strategies and enabling policies will only be possible if a city-wide picture of the critical role of urban agriculture is clearly established.

Hydroponics Firm Launches Urban ‘Farm-In-A-Box’

Tuesday 21st March 2017, 16:38 London

Hydroponics Firm Launches Urban ‘Farm-In-A-Box’

Company aims to reduce food miles and boost nutritional value with hydroponic farming equipment for grocery stores, restaurants, and schools

Urban farming company groLOCAL is launching equipment to enable businesses to cut food miles and grow their own fresh produce on site.

The groTAINER shipping container - which the company describes as a fully-configured "farm-in-a-box” - allows grocery retailers, restaurants and schools among other businesses to grow produce such as herbs, spices and micro-greens on their own premises.

This ensures that produce maintains its nutritional value, according to the company, which highlights the fact that a tender soft tissue plant loses 80 per cent of its essential oils and half of its vitamin and mineral content within the first day after picking.

“It’s possible for businesses to grow highly nutritious produce at just a fraction of the cost of buying from suppliers,” the firm added in a press release.

David Charitos, managing partner of groLOCAL, said: “Standing out from the crowd in the food market can be a challenge. But having the ability to grow your own spice, greens, and herbs can mean you have something different to offer customers and really gives you the flexibility to try different flavours, knowing that all the ingredients are fresh.

“Having the option to grow some of the produce used means cutting down on expenses in the long run too."

The team behind groLOCAL are experts in hydroponic farming – the process of growing plants without soil, using nutrient solutions instead. This farming method makes it possible for businesses to grow plants anywhere, including urban environments.

The farm containers come with a fully-fitted production unit, including preparation and packing areas, meaning businesses do not need to find further space in their existing premises to accommodate hydroponic farming.

groLOCAL offers businesses the choice of either purchasing a groTAINER outright or leasing the equipment.

Vertical Farming, The Future of Crop Growth

Vertical Farming, The Future of Crop Growth

By Riana Soobadoo -

March 21, 2017

The future of farming is on the up and up, literally. With today’s society constantly changing, progressing, and evolving, everything that can be revolutionized will be. Now, with the emergence of vertical farms on the rise, it seems that the future of urban farming is here.

Vertical farming refers to when food is produced in vertically stacked layers, usually in a greenhouse or warehouse. These farms use indoor farming techniques and a variety of controlled environmental agriculture technology to control environmental factors in their favor. Such as the use of LED lights to substitute natural light that is missing indoors. Never having to be subjected to the elements, or worrying about what season it is, indoor farming allows for completely controlled growth of produce.

Because of its potential to transform agriculture globally, vertical farming is quickly becoming the next step forward in agricultural production. Although the produce cannot technically be labeled as organic, because it is not grown in soil, vertical farming processes are completely pesticide free, require no sun, and use 95% less water than traditionally field-grown crops. Additionally, due to the faster harvest time, crops grown through vertical farming produce a higher annual yield than those grown through traditional agriculture methods. The increased popularity in the sector has led to a surge in numbers of companies looking to make their mark on the industry.

The first of these, AreoFarms, is the one of the world’s largest indoor vertical farms. Based in Newark, New Jersey, USA, AreoFarms has been farming indoors since 2004. AreoFarms uses a technique called aeroponics. Aeroponics uses 40% less water than traditional hydroponic farming. It also utilizes smart LED technology to customize the amount of light used for each plant type. This energy efficient process has the potential to change the farming industry forever. Mark Oshima, a co-founder of AeroFarms explains that they use:

“IN-DEPTH GROWING ALGORITHMS WHERE WE FACTOR IN ALL ASPECTS FROM TYPE AND INTENSITY OF LIGHT TO NUTRIENTS TO ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS LIKE TEMPERATURE, HUMIDITY, AND CO2 LEVELS, AND WE CREATE THE PERFECT RECIPE FOR EACH VARIETY.”

Another emerging vertical farm is Bowery Farming. Based in New York, New York, USA, Bowery Farming first opened their doors in 2015 and has recently opened another location in New Jersey, USA, to increase their reach. Labeled as post-organic, Bowery’s products never travel more than 100 miles to guarantee freshness. Attracting increasing interest of new Investors, Bowery Farming has quickly become a big name in the vertical farming industry. They currently produce five leafy vegetables, including baby kale, lettuce, and arugula, and one type of herb, basil. These greens are non-GMO and do not need to be washed when taken home.

In Japan, the Pasona O2 building is yet another example of vertical farming; with 6 rooms of farms, 100,000 square meters, and growing over 100 different types of produce, this farm employs young men and woman who are struggling to find jobs or have an interest in farming. The company advocates the individual development of these men and woman, passionate about seeing them succeed in their industry. Each room at Pasona O2 houses something different: room 1 houses a flower field, room 2 is a herb field, room 3 a rice field, room 4 a fruit and vegetable field, room 5 is vegetables, and room 6 is for lettuce and the seeding room. Each room is set to the proper environmental specifications needed to grow and sustain the crops.

Unfortunately, as revolutionary as vertical farming is, the start-up costs are astronomical, which can be a problem for companies trying to expand. One company in particular, the Atlanta based PondPonics, was able to get their productions costs down lower than anyone else. Unfortunately, when offered a $25 million dollar annual contact with Kroger they could not get the funds to build the necessary facilities to grow in such volumes. Ultimately, PodPonics was forced to close their doors as the running costs became too high.

This is not the case for every company. As time moves forward we will begin to see a shift in the attitudes of investors, and interest in vertical farming will continue to grow. The future of agriculture is looking greener and greener. With vertical farming on the rise, we can expect to see a change in the industry unlike ever before.

U of T Scarborough Explores How Urban Agriculture Intersects With Social Justice

U of T Scarborough Explores How Urban Agriculture Intersects With Social Justice

March 21, 2017 | By Don Campbell

A summit hosted at U of T Scarborough this month looked at urban agriculture and the role of community gardens in Toronto

As Toronto continues to grow, urban agriculture may play a more significant role for people seeking alternative sources of nutritious and affordable food, U of T researcher Colleen Hammelman says.

Hammelman has examined urban agriculture in such cities as Medellín, Colombia, and Washington, D.C. She explored the role of urban agriculture in the GTA and social justice at a one-day conference organized at U of T Scarborough this month.

“Urban agriculture brings a lot of value to a city, especially in terms of sustainability, but a key element is how social justice also fits into the conversation,” says Hammelman.

While urban agriculture is widely practiced in many respects, it’s also misunderstood, particularly the important role it plays in migrant communities both culturally and nutritionally, notes Hammelman, who is a post-doc researcher at U of T Scarborough's Culinaria Research Centre.

From her experience, urban agriculture not only supplements food budgets by giving access to fresh food many can’t afford, but it also provides “spaces of community resilience” where residents can come together for a common purpose.

“Community gardens also provide important avenues of support for new Canadians,” she adds.

The conference featured a variety of speakers including Kristin Reynolds, author of Beyond the Kale, and Toronto Councillor Mary Fragedakis, along with members of various community organizations like Black Creek Community Farm, Toronto Urban Growers and AccessPoint Alliance. Undergraduate and graduate geography students also had a chance to meet with participants to talk about how social justice fits into the conversation around the urban agriculture movement.

There are about 200 spaces ranging in size that are designated for community gardens across Toronto where people can grow food.

“It’s an active and growing movement in the city, but there are challenges in trying to expand,” says Hammelman, pointing to resources needed for starting up a garden and finding adequate spaces and clean soil, which is no easy feat given Toronto’s industrial past.

She pointed to work being done by Malvern Action for Neighbourhood Change in supporting three community gardens and collaborating with other organizations for a project that will establish market farms in Hydro corridors as microenterprises. The work being done there in creating community gardens focuses a lot on addressing some of the food security issues in Malvern.

Hammelman sees the university playing a role in working together with community partners to help navigate some of the challenges involved in establishing opportunities for urban agriculture.

“There’s work to be done on making sure people growing food in community gardens can be adequately compensated for their labour, but also ensuring that the food being grown is still affordable for those who need it,” she says.

A summit hosted at U of T Scarborough this month looked at urban agriculture and the role of community gardens in Toronto (photo by Ken Jones)

The Future of Food

The Future of Food

MARCH 20, 2017 18:06

From computer-monitored growing chambers and vertical farms to superfoods, the increasing needs of a burgeoning population have led to technology-fuelled innovations in agriculture

If history is to be believed, the plow and seeder were invented by the Mesopotamian civilisation in 3000 BC. In 2017, if you do a Google search on technology used in farming, the results would display similar tools, with the exception of the innovations of the last century.

How does limited evolution in farming technologies fare against the challenge of feeding a population this world has never seen before? In the late 1950s, when serious food shortages occurred in developing nations across the world, efforts were made to improve the growth of major grain crops like wheat, rice and corn, by creating hybrid grains that responded well to the application of fertilisers and pesticides. This meant, especially for countries in Asia, high yields per hectare. However, the repercussions of ever-increasing use of chemicals are now visible, with many diseases being traced back to the use of chemically-grown food. A technology that was supposed to help feed the growing world has proven to be more hindrance than help. Today, more people are moving towards organic produce, but the question remains – how do we connect growing more and better with healthy and organic?

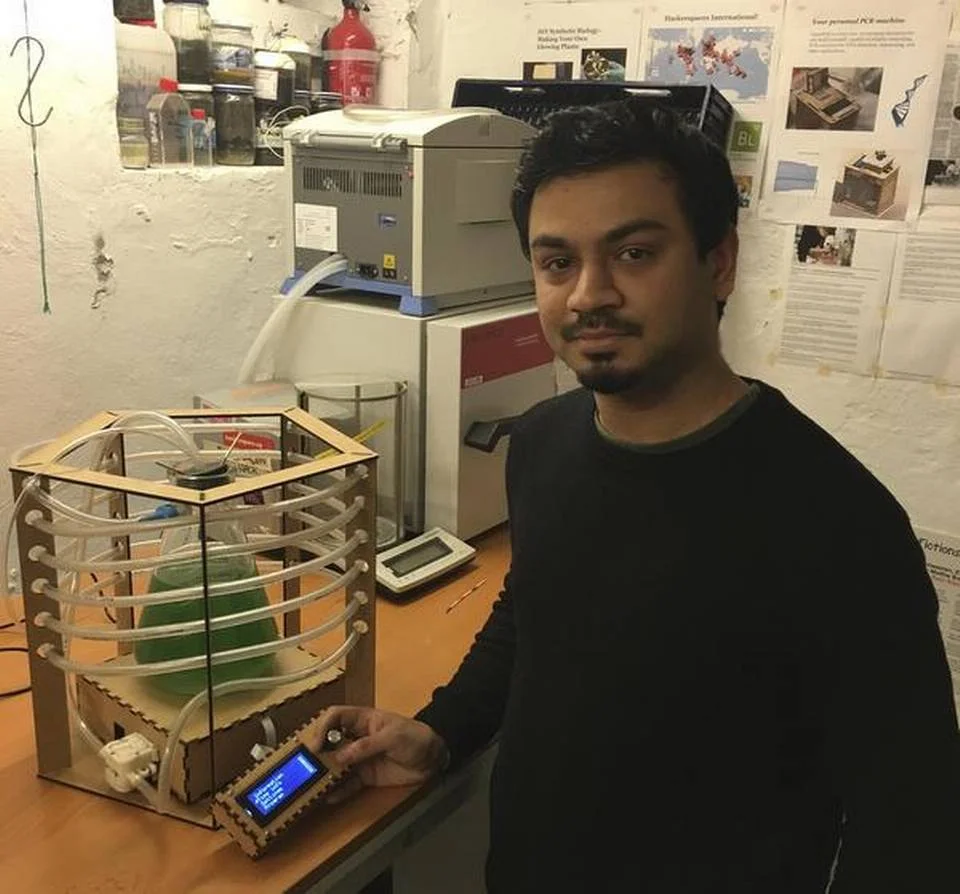

At a TED Talk in December 2015, Caleb Harper, Principal Investigator and Director of Open Agriculture Initiative at MIT Media Lab, gave a peek into the future of urban agricultural systems.

His team has created a food computer, a controlled-environment agriculture technology platform that uses robotic systems to control and monitor climate, energy, and plant growth inside a specialised growing chamber. Climate variables such as carbon dioxide, air temperature, humidity, dissolved oxygen, potential hydrogen, electrical conductivity, and root-zone temperature are among the many conditions that can be controlled and monitored within the growing chamber. While the food computer remains a research project at the moment, there are companies using technology in their current food-growing ecosystems.

Japan has been experimenting with Sandponics, a unique cultivation system that uses no soil, only sunlight and greenhouse facilities.

A small section of sand is supplied with a mix of essential nutrients, and in some cases, the same section of sand has been in use for over three decades. The first systems were developed in the 1970s and are still evolving today. They have proved to be not just efficient, but affordable and scalable too.

The 750-square-kilometre island of Singapore, feeds a population of five million by importing more than 90% of its requirement. With available farmland being low, the only way to grow food is to go vertical. This is where vertical farms and farming entrepreneurs and companies such as Sky Greens have come up with innovative solutions that are not resource-intensive.

India initiatives

India isn’t far behind in exploring urban farms either. Chennai-based Future Farms, Jaipur-based Hamari Krishi and a few others are bringing the urban farm revolution to India.

Most of the above technologies will help increase the yield in terms of quantities, but what about the nutrient value? Around the world, companies and researchers are spending time to find the next superfoods, something that our species might not be able to survive without. While some might think cricket (yes, the insect) flour is too extreme, there are those who consume it. Keenan Pinto, an engineer with a background in molecular biology and biotech, has created a bio-reactor for micro-algae after hearing that Spirulina could hold the key to fighting malnutrition. Companies such as Soylent (USA) and Onemeal (Denmark) have been making highly-engineered minimalist food powered by micro-algae, that only need water to make a liquid meal with 20% of daily nutritional value of a person.

NASA’s data has already shown evidence of drastically depleting groundwater resources in North India, and Pinto believes this makes initiatives like the Soil Health Card (a scheme launched by the Government under which farm soil is analysed and crop, nutrient and fertiliser recommendations are given to farmers in the form of a card) the need of the hour.

In the past two years, the image of agriculture and farming technologies has changed from a sickle and plough to computers and vertical farms.

As need grows, our food systems are destined to evolve, and it is our job to evolve with them.

The Scotts Miracle-Gro Foundation Announces Community Garden Grant Recipients

The Scotts Miracle-Gro Foundation Announces Community Garden Grant Recipients

By GlobeNewswire, March 20, 2017, 08:00:00 AM EDT

More Than 100 Projects to Receive Funding Through GRO1000 Grassroots Grants Program

MARYSVILLE, Ohio, March 20, 2017 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- To mark the first day of spring and celebrate the start of the community gardening season, The Scotts Miracle-Gro Foundation today announced more than 100 non-profit organizations nationwide will receive 2017 GRO1000 Grassroots Grants. The organizations awarded will use the funding to improve their communities through the development of public gardens and greenspaces.

Now in its seventh year, the GRO1000 Grassroots Grants are part of The Scotts Miracle-Gro Foundation's support to bring gardens and greenspaces to more people and communities, particularly to those in need. GRO1000 will support the creation of more than 1,000 community greenscapes by 2018, which aligns with The Scotts Miracle-Gro Company's 150th anniversary.

"Helping communities across the country experience the powerful benefits of gardening and its ability to transform lives is a privilege for The Scotts Miracle-Gro Foundation," said Foundation President and Board Member Jim King, who also serves as SVP and Chief Communications Officer for ScottsMiracle-Gro. "As we look forward to the final year of the GRO1000 program, we are committed now, more than ever, to connecting more communities to these benefits."

From children's learning gardens to pollinator habitats, urban farms to healing gardens, GRO1000 has supported over 830 community-based projects nationwide since 2011. Projects have resulted in more than 10.7 million square feet of greenspace revitalized, more than 266,000 pounds of produce donated annually and more than 65,000 youth positively impacted through hands-on experiences with nature, according to data collected from previous GRO1000 Grassroots Grants recipients. A full list of this year's recipients can be found at www.GRO1000.com.

In addition to the Grassroots Grants, The Scotts Miracle-Gro Foundation and its national partners, the U.S. Conference of Mayors, Plant A Row for the Hungry, the Garden Writers Association Foundation, KidsGardening.org, and Franklin Park Conservatory and Botanical Gardens, are building public community gardens and greenspaces in New Bedford, Mass.; New Haven, Conn.; Rochester Hills, Mich.; and Santa Monica, Calif., in 2017. More information on the GRO1000 program can be found at www.GRO1000.com.

About The Scotts Miracle-Gro Foundation

The mission of The Scotts Miracle-Gro Foundation is to inspire, connect and cultivate a community of purpose. The Foundation is deeply rooted in helping create healthier communities, empower the next generation, and preserve our planet. The Foundation is a 501(c)(3) organization that funds non-profit entities that support its core initiatives in the form of grants, endowments and multi-year capital gifts. For more information, visit www.scottsmiraclegrofoundation.org.

Contact: Molly Jennings The Scotts Miracle-Gro Company 937-681-7683 (desk) 561-350-5734 (mobile) Molly.Jennings@Scotts.com Kailyn Longoria Fahlgren Mortine 614-383-1633 (office) 646-919-1234 (mobile) kailyn.longoria@fahlgren.com

Source: The Scotts Miracle-Gro Company

Jessica Fanzo Calls For More Accountability Across the Food System

Jessica Fanzo, PhD, Director of the Global Food Ethics and Policy Program at Johns Hopkins University, is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit, “Investing in Discovery,” which will be held in collaboration with Tufts University and Oxfam America on April 1, 2017

Jessica Fanzo Calls For More Accountability Across the Food System

Jessica Fanzo, PhD, Director of the Global Food Ethics and Policy Program at Johns Hopkins University, is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit, “Investing in Discovery,” which will be held in collaboration with Tufts University and Oxfam America on April 1, 2017.

Dr. Fanzo has an extensive background in nutrition education and policy development through her work as an Assistant Professor of Nutrition in the Institute of Human Nutrition and Department of Pediatrics and as the Senior Advisor of Nutrition Policy at the Center on Globalization and Sustainable Development at Columbia University. Before her transition to academia, Jessica held positions in the United Nations World Food Programme and Bioversity International, both in Rome, Italy. Prior to her time in Rome, she was the Senior Nutrition Advisor to the Millennium Development Goal Centre at the World Agroforestry Center in Kenya. She was the first laureate of the Carasso Foundation’s Sustainable Diets Prize in 2012 for her work on sustainable food and diets for long-term human health. Jessica has a PhD in nutrition from the University of Arizona.

Dr. Jessica Fanzo urges understanding of the impact daily food, nutrition, and policy choices have around the world.

Food Tank had the chance to speak with Dr. Fanzo about her expertise in the linkages between agriculture, nutrition, health, and the environment in the context of sustainable and equitable diets and livelihoods.

Food Tank (FT): What originally inspired you to get involved with your work?

Dr. Jessica Fanzo (JF): I did all my training in nutrition—my bachelor’s, master’s, and PhD. I moved away from from nutrition and then came back to it when I started to work in Africa on food systems. I came back to nutrition to better understand the integration of agriculture, nutrition and health. So, my inspiration for doing the work is how to make food systems healthier in low-income settings.

FT: What makes you continue to want to be involved in this kind of work?

JF: I think the food system and the plethora of food environments that we are exposed to every day are incredibly complex, and largely unhealthy and inequitable at the moment. It is a complex problem that requires a complex set of solutions. It is not an easy road to take, but I think it keeps me very engaged. There are so many different actors and players that you come across when working in food systems which makes this work fascinating.

FT: Who inspired you as a kid?

JF: My parents were incredibly influential. Coming from an Italian-American working class family, food served as a central point of socializing and gathering together.

FT: What do you see as the biggest opportunity to fix the food system?

JF: A lot is happening in the area of local solutions to improve food systems. There is a lot of innovative work coming out of low-income countries that we, in high-income countries, can learn from. There is a lot of young thought leaders residing in many low income/middle-income countries who are shaping not only the food system but how their countries are governed. We are seeing this resurgence of young people wanting to disrupt the system and we need to harness the intelligence and energy that they bring to food system issues. We need to find a way to give young people the opportunity to contribute to real change. I hope we don’t miss it.

FT: Can you share a story about a food hero who inspired you?

JF: There are so many in my immediate life, and there are so many that I worked with. I have to say Danielle is amazing. She is helping to create a movement in the United States. Her ability to share information and create networks, and again, reaching a younger generation. Marion Nestle is in the prime of her career and has been a great on the ethics side – calling out conflicts of interest. I work a lot in East Timor, and there is this amazing young woman named Alda Lim. She has started this restaurant in the capital city Dili, and she only employs Timorese youth. She is teaching them all about the indigenous foods of Timor-Leste. She teaches them how to cook it, how to make excellent cuisine out of it, how to run a restaurant. She has maybe about 15 employees, of young people, who didn’t have jobs. She is spreading the word about local foods in Timor and bringing back this whole culture of Timorese taking pride in their local cuisine. It’s very cool, so she is one of my heroes too.

FT: What is the most pressing issue in food and agriculture that you would like to see solved?

JF: I think we need more accountability across the food system. Who owns the food system, or who should be the stewards of food systems? If we don’t have someone who owns it or a steward that looks after it, we have no accountability in the food system. The other huge issue that I grapple with is, do people have the right to eat wrongly? The impacts of what we eat impact climate change, and those living in low-income countries will suffer more from the decisions that we make. We all need to hold ourselves accountable at this point; we are living in a very interconnected, globalized world.

FT: What is one small change everyone can make in their daily lives to make a big difference?

JF: In high-income countries, people need to stop consuming so much. Not just food, it’s everything. We consume on a massive scale.

FT: What advice would you give to President Trump and the U.S. Congress on food and agriculture?

JF: I would advise him and the U.S. Congress to participate in the Conference of the Parties (COP) and take the science around climate change seriously. The U.S. should stay the course and not back out on the agreements made during COP21, for the future of ourselves and the planet.

McNamara: “To Fix The Food System, Move It Back Into The Hands of More People”

Brad McNamara, CEO and co-founder of Freight Farms, is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit, “Investing in Discovery,” which will be held in collaboration with Tufts University and Oxfam America on April 1, 2017.

Brad McNamara, CEO and co-founder of Freight Farms, is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit, “Investing in Discovery,” which will be held in collaboration with Tufts University and Oxfam America on April 1, 2017.

Freight Farms is an agriculture technology company that provides physical and digital solutions for creating local produce ecosystems on a global scale. Brad and his co-founder, Jon Friedman, developed the company’s flagship product, the Leafy Green Machine, to allow any business to grow a high-volume of fresh produce in any environment regardless of the climate. His hope is for Freight Farms to be scattered across the globe making a dramatic impact on how food is produced.

Food Tank had the chance to speak to Brad about his work developing Freight Farms and his vision for the future of our food system.

Brad McNamara, CEO and co-founder of Freight Farms, is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit, “Investing in Discovery.”

Food Tank (FT): What originally inspired you to get involved in your work?

Brad McNamara (BM): It was a coming together of many different factors. My co-founder, Jon, and I had worked together in the past, and we were both intrigued by the food system and how we could make a difference. Around 2009, Jon was focused on food systems and system design, and I was passionate about the purity of food and the increasing trend towards food awareness. When the two of us first reconnected over a cup of coffee (and then a beer), we got to talking about the complexity of the food system and what we could do to combine our interests. With backgrounds in design and environmental science, our goal was to research methods to allow urban agriculture to emerge as a competitive industry in food production. We mainly focused on rooftop development, then determined the criteria for success and scale to be outside the realm of possibility with agricultural installations that were already in existence. When costs and logistics soared, we turned to shipping containers (there’s Jon’s design background coming into play), and the idea for Freight Farms took off with the goal to build farms in areas that couldn’t support more traditional methods.

FT: What makes you continue to want to be involved in this kind of work?

BM: Our world and our climate are changing, and it is so apparent that there is more work to be done. According to the U.N., food production needs to increase 70 percent by 2050, to feed an ever-urbanizing population. Land and water scarcity take on even more pressing importance, as does urban agriculture. The future is so much bigger and more complex than we could have ever imagined. Over the past few years, we’ve gotten to witness the emergence of a new industry of agriculture technology, and it’s poised to make a dramatic impact on the food system. One of the most amazing things we’ve been able to watch is how many are interested in joining the movement towards a better future. Our network of freight farmers are making dramatic impacts on their local food systems every day, drastically improving food security in their community. They inspire all of us to continue this work.

FT: Can you share a story about a food hero who has inspired you?

BM: My food hero is a customer of ours. His name is Ted Katsiroubas, and he runs Katsiroubas Bros. Fruit and Produce, a wholesale produce distribution company located in the heart of the city of Boston. The business is over 100 years old and was handed down from generations before. I admire how Ted has innovated in the face of a dramatically changing food landscape. As the demand for local, fresh produce has risen, the company expanded to begin working with local farms in the region to meet demand. For those familiar with wholesale distribution, sourcing locally can be a difficult task especially when you are restricted by the growing seasons and volume constraints of small local farmers. That’s why traditionally wholesale distributors rely on shipping produce long distances from warmer climates. But Ted brings a fresh approach to an old school industry. He continues to push the envelope and propel the industry to stay on top of the latest technology through collaboration with other distributors. If anyone were to fall into the category of my food hero, it would be Ted because of his willingness to look to the future and go against the conventional wisdom of how the food industry tells him to conform.

FT: What do you see as the biggest opportunity for fix the food system?

BM: I think the biggest opportunity to fix the food system is to bring it back into the hands of the people. By transitioning to a more decentralized food system, and minimizing the gap between consumers and producers, we will take a critical step towards an environmentally and economically sustainable food system. I think all the various types of technology, the hardware, the software, and the social awareness, all point in the direction to empower the individual. So the real opportunity to fix the system is to utilize what we know to be true—when you give opportunity and power to regular people from all walks of life, that’s when you can change a whole system.

FT: What would you say is the most pressing issue in food and agriculture that you would like to see solved?

BM: There are so many people advocating for a better food system, and we all must be better at communicating and cooperating if we want to make an organized effort to challenge the way things operate currently. From small farmers and producers to organizations and companies. What has become incredibly apparent in the past couple decades is that there is no one size fits all solution. Whether it’s urban or indoor agriculture, hydroponics, aeroponics, aquaponics, or traditional soil-based farming, we all play an important role. We need to have a more holistic view of the food system and how each method can contribute to a better future. If we don’t all work together, it’s going to be difficult to disrupt BigAg. I think taking a broader view is key. There has been so much progress made in agriculture, but we still have a long way to go to create a food system that will serve future generations. It is important to continue working with and connecting with each other to empower and support the next generation of farmers.

FT: What is one small change everyone can make in their daily lives to make a difference?

BM: Maybe it is a bit cliché, but the notion of voting with your dollars. I’m sure others have said it, but it is so important. If every consumer changed 5 percent of their food shopping habits by buying more seasonal and local produce, the impact would be enormous in changing the landscape of the local grocery store.

FT: What advice can you give to President Trump and the U.S. Congress on food and agriculture?

BM: My advice is to be conscious of all the complexities present within the food and agriculture system. There are so many moving pieces that small shifts in the workforce, water use, and the climate have a massive impact throughout the entire system. It is essential to keep a holistic understanding of the relationships between all the components in our food and agricultural system and to consider the ripple effect policy decisions will have on the smaller players involved.

Click here to purchase tickets to Food Tank’s inaugural Boston Summit.

Brad McNamara, CEO and co-founder of Freight Farms, is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit, “Investing in Discovery.”

Your Relationship With Fish Is About To Change

Your Relationship With Fish Is About To Change

Monica Jain | Monica Jain leads Fish 2.0 and Manta Consulting Inc. She is passionate about oceans, impact investing, fisheries and building networks around these themes.

A wave of change is upending the seafood business as we know it. Here’s what it means for everyone from investors to fish stick aficionados.

It’s 2027, and we’re no longer gorging ourselves on shrimp. Or tuna. Or salmon. Not because they’ve disappeared from the oceans or we’re appalled by how they’re produced, but because we’re eating so many other delicious fish from land and sea — like porgy, dogfish, lionfish, barramundi, and others we’ve yet to meet.

We also know exactly what fish we’re eating and where it comes from — sometimes we even know the fishers by name — so we can make confident choices based on nutrition and sustainability factors. Fishing communities are healthier too: they serve local as well as export markets, and new seafood products boost their economic base. Unsustainable seafood just doesn’t sell: consumers walk away from it the way they avoid foods with transfats today.

This scenario might sound ridiculous to people focused on the historically slow rate of change in an industry with a complex and often low-tech global supply chain. People assume that change will continue to plod along. I don’t believe that.

The pace has already picked up dramatically. Governments, big industry players, entrepreneurs and investors are focused on seafood sustainability like never before. Several drivers are kicking in at once.

- We’re realizing that we’re going to run out of food if we don’t find alternative supplies and environmentally sound production methods. Seafood is a healthy, high-quality protein source. It tastes good and we can grow it sustainably.

- People are more interested in where their seafood comes from and what’s in it. And they increasingly see quality and sustainability as linked product attributes — I hear this from seafood buyers all the time.

- Emerging technologies that will clear up seafood’s murky supply chain or allow aquaculture to flourish are being developed by multiple players, big and small.

- Investors are realizing that the seafood market is huge, and they’re seeking opportunities to make change in it. Feed for farm-raised fish alone is a multibillion-dollar opportunity.

Over the past five years, as I’ve built the Fish 2.0 business competition, I’ve seen an overwhelming number of creative ideas bubbling up with highly qualified entrepreneurial teams behind them. Their innovations, combined with powerful social and environmental forces, are creating a new world both above and below the ocean’s surface.

How seafood is like lettuce

It’s not so unlikely that this magnitude of change will happen quickly. What happened with greens in produce is going to happen with seafood: more variety, more demand for local products, greater awareness of sustainability factors, a focus on quality, and the rise of seafood superfoods. We’re already seeing seafood follow the broader food world. The Emerging Trends to Watch in 2017 report from Rabobank’s senior analyst for consumer foods, Nicholas Fereday, calls out increased attention to food waste, more capital flowing to early-stage consumer brands that respond to unmet consumer needs, the demand for supply chain transparency and ethical sourcing, and the rise of personalized approaches to nutrition. These trends already are emerging in the seafood industry.

Considering them in light of the momentum behind solutions to seafood’s specific challenges, I see seven key changes happening in seafood over the next decade.

1. Diversity rules.

Right now, seafood is in its iceberg lettuce stage. Americans generally eatfive types of seafood: shrimp (the most popular by a wide margin), followed by tuna, salmon, tilapia, and Alaskan pollock (usually in fish sticks and the like). We’re about to grow out of that. Is lionfish the new kale? I don’t know, but I am confident that within 10 years, people will eat a much greater diversity of seafood, they will trust the people who introduce new items to them, and they’ll always be on the lookout for something new, just as we are with our greens these days.

The trends outlined below will contribute to the shift toward diverse seafood diets. We’re starting to see a glimmer of this shift with sustainability-focused chefs like Bun Lai introducing diners to invasive species or fish that used to get tossed off the boat, and companies like Love the Wild packaging sustainably farmed fish with sauces to make trying something new easier than eating the same old thing.

2. Seafood goes local.

Every place where seafood is captured will have supply chains that put local seafood in local markets. Right now, locavores often get stumped by seafood. Even if you live on the coast of a major fishery, it’s hard to get local fish outside of high-end restaurants. The supply chain simply isn’t set up for local distribution. In Monterey, for example, there’s no landing and storage facility for local seafood. And that is typical of coastal regions throughout the world. Consumer demand, combined with the need for local fishers to diversify their supply chains and earn higher prices, is changing this situation.

You can see it in the emergence of community-supported fishery (CSF) options, which apply the direct-from-the-farm (CSA) model to seafood. The Wall Street Journal counted 30 CSFs in 2014; LocalCatch.org’s Seafood Locator now lists 75 CSFs, and the organization believes there are many more. Real Good Fish sells local seafood this way in Northern California, and Catch of the Season does it in Alaska, to name just two of the many operations I know.

3. Traceability and transparency are the price of admission.

Remember when coffee was just coffee? Now we know where it’s from, who picked it, if it grew in shade or sun, and more. Ten years from now, I believe that seafood will be the same. We’ll know where our seafood came from, how it was captured, and how long it’s been out of the water. This information will become so common that there won’t be a price differential for pedigreed fish, and mystery fish just won’t have a market in the U.S.

In fact it’s already happening, as tightening government regulations, expanding consumer interest in knowing where their food comes from, and technological innovation converge. Entrepreneurs worldwide are targeting links throughout the supply chain, including TRUfish, which offers DNA testing of sample fish from batches, allowing resellers and consumers to verify that the species on offer are what the seller says they are; Salty Girl Seafood, which allows consumers to trace their preseasoned frozen or smoked fish via a code on the package; and Bangkok-based FairAgora Asia’s Verifik8 software, which tracks, manages and displays social and environmental data on seafood operations.

4. We solve the fish feed problem.

Farmed fish need food, and it’s in increasingly scarce supply. Fish eat other fish in the wild, and right now, they do in farms too. Fish meal and fish oil also turn up in foods for people and pets. With wild forage fish stocks either stable or declining, demand is outpacing supply as aquaculture grows and fish feed prices are rising. This is obviously not sustainable. The fish feed industry is a huge target for innovation, and we’re starting to see results from the hunt for nutritious fish feeds that don’t require other fish. Algae, soybeans, oil seed, insects and bacteria are all getting trials. Development is proceeding quickly enough to say that seafood produced at scale without fish-based feeds is a realistic vision for the next decade.

The result will be not only a more stable supply of feed for aquaculture, but also new opportunities for islands to diversify their economies by growing locally abundant new feeds using algae and seaweed — perhaps leading to even more nutritious seafood products on our tables.

5. Aquaculture fills more of our seafood plate.

It has to. We can’t keep drawing on wild fish stocks, and seafood is one of the few animal proteins that can we grow sustainably. The advent of new fish feeds will fuel aquaculture expansion. At the same, innovative technologies and farming approaches for scalable closed-loop aquaculture systems on land and responsible open-water systems will provide healthier, more delicious fish. Already, Acadia Harvest is selling California yellowtail, or “hiramasa,” grown on land in Maine; Kampachi Farms is pioneering sashimi-grade fish farming in the Sea of Cortez; and SabrTech’s RiverBox system, which reduces pollution from farm runoff and grows an algae-based feed from the captured wastewater, and Bangkok-based Green Innovative Biotechnology’s advanced feed supplement could remake aquaculture in Southeast Asia.

6. Waste turns into value.

Waste will drop from being about 40 percent of seafood to about 10 percent over the next 10 years. Not only will we use more of the seafood we capture, we’ll also turn today’s wasted byproducts into valuable co-products. People are making leather out of fish skins. Fish scales, which are highly conductive, could be useful in solar cells and other applications. Less exotically, seafood entrepreneurs are looking at upcycled food uses for what’s often treated as waste, such as bottarga (cured grey mullet roe) and salmon jerky made from flesh that is typically discarded.

7. Sustainability is a given.

Sustainability will become so closely associated with quality in consumers’ minds that it’s nonnegotiable. Consumer demand for organic food continues to show double-digit growth, and sustainable seafood is primed to follow that path. We’ll want sustainable seafood because it’s better. In turn, businesses will recognize that a strong sustainability profile is critical to maintaining market share. We may even cease to use the term “sustainable seafood,” because sustainability will just be intrinsic to the word seafood.

A connected industry makes this future real

The innovations we need won’t emerge from a vacuum. To make this vision real in a short time frame, partnerships are essential, just like in the tech world. In order for any of this to happen we need greater connectivity in seafood’s vast, complex global supply chain. The links in that chain — including investors — need to get to know one another. Those connections will breed product and business model innovations. Seafood will move through a distributed network instead of a fragmented supply chain. Together, we’ll spark something new.

And we’ll be able to have our fish and eat them too.

Cuba In Your Backyard: The Indian Startup Bringing Organic Farming to Your Rooftop

Cuba in your backyard: The Indian startup bringing organic farming to your rooftop

Homecrop gives you everything you need to make your own small farm at home.

- Shilpa S Ranipeta

- Tuesday, March 14, 2017 - 19:47

Before the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba was heavily dependent on the USSR for petroleum, fertilizers, pesticides and farm products. But when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, and eventually sanctions were imposed on Cuba, the country was left in the lurch. According to cubahistory.org, the country lost nearly 80% of its imports and exports and the GDP plummeted by 34%.

The effects were seen almost immediately. There was acute food shortage. Calorie intake fell to less than half of what it was before. In such a situation, Cubans had no choice but to grow food themselves. Tiny pockets of land emerged all across the country. What started as a concept called Organoponicos is now being replicated around the world as a sustainable urban farming solution.

It’s as simple as converting your terrace, backyard or balcony into a small farm. And at a time when almost every fruit and vegetable being grown is sprayed with pesticides, what if you could control what goes into growing your food? This is where 26-year old Manvitha Reddy stepped in to start Homecrop – a startup that helps you grow pesticide-free vegetables at home. Reddy has designed rooftop and backyard kits that have everything you need to make your own farm at home.

The main technique used here is square foot gardening. In areas as small as 15 square feet, Homecrop gives you a kit that includes a high intensity polystyrene trough, a leak proof support structure for trellis, a shade net, a mat for drainage, garden tools, natural growth enrichers and service from the Homecrop team.

Simple farming techniques used since ancient times are incorporated into building a home farm. For example, all of Homecrop’s farms are soil-free. Instead, Coco peat is used. This does not require much depth and it lets roots take in more nutrients and gives them more aeration. The crops are irrigated using an age-old irrigation method called Olla’s where water is filled in clay pots, which are porous enough to let water seep through. This reduces the use of water by 60-70% letting you water the plant just once in every 2-3 days. Most importantly, rooftop gardens bring down a house’s temperature by a few degrees.

Reddy launched Homecrop in January this year with an initial investment of just 5 lakh rupees. Ideation took a year under the guidance of National Academy of Agricultural Research Management (NAARM)’s incubator a-IDEA. The incubator helped her research various agricultural methods for her idea and provided her with access to vendors for the kit.

She started by catering to households and is now targeting gated communities. “There is so much unused space in a house or a gated community. The idea is to use whatever available space there is, to make edible landscapes,” Reddy says.

Homecrop currently offers two kits – the budget kit, which can be used for backyards at a cost of Rs 7500 and the premium kit, which can be used for rooftops at a cost of Rs 15,000. With operations currently only in Hyderabad, Homecrop has so far covered 400 square feet.

Once it completes 300 installations, Homecrop will look at raising additional funds.

Homecrop is now working with NAARM to standardise the process. It is also coming up with kits for balconies in a month and a half. This will be a vertical self-watering tower on which one can grow up to 18 plants in an area as less as two square feet. Post this, Homecrop will launch do-it-yourself kits and expand operations nationally.

And if all of Homecrop’s efforts bear fruits, or vegetables, it hopes to break even in the next one year

New Technologies Are Creating New Ways To Grow Fresh Produce

New Technologies Are Creating New Ways To Grow Fresh Produce

Vertical farming operations are popping up everywhere and this new technology can complement traditional agriculture

AF Columnist

Published: March 13, 2017

Opinion

We were in Holland and our group stood in amazement at the growing capabilities of Koppert Cress.

Owner Rob Baan, a policeman’s son turned world entrepreneur, was emphatic that neither soil nor light is needed to grow food — only heat. And all of those components could be provided by technology, he said.

In a large glasshouse Baan grew microgreens in cellulose under LED lights. In the vast kitchen on site, we tasted the bounty and I remember it still: an absolute bursting of flavour and texture exploding on the palate.

The Business Plan Was Simple.

Take the product to the chef first, ask them what they liked, disliked, and were looking for in food trends. Go home, turn on some LED lights, and grow what the chef wants. Baan’s global empire (Koppert Cress distributes microgreens across Europe and has a U.S. division) is proof that fresh food can be grown inside. It is the ultimate urban farm.

Later, in a cooking class in Canada, I noted that chefs had microgreen boxes or microgreen appliances in the kitchen. Again, no natural light and no soil were present, and the greens were grown in stacked trays. But it made a huge difference to a dish when that fresh green top was pruned off the tray from the inside of that black box. A variety of these are now available for home kitchens. Retail stores in the U.K. introduced living vegetable aisles where the food was grown on site and the customer picked it from the vertical display.

And in travel, I’ve found hotels now boast rooftop gardens and restaurants are quick to highlight their little herb patch. That’s good news because it means we have a movement to grow food that has been unmatched in recent history. How far we go is really limited only by imagination. We can grow food in a field or black box, and both will metabolize similarly.

European scientists have long been curious about food produced in a black box. Their quest for perfection demands vegetables and fruit be fresh and without blemish. Not only must the shape and colour be right, but so must the degree of ripeness. Just as the Chinese form the square watermelon in a box, growing food in black boxes allows for the perfect product every time.

Why is This So Important To Traditional Farmers? And Why is it a Threat?

While it is true that farming is truly evolving on many technical platforms, the idea of food production indoors and without soil or light is leaping ahead in the area of vegetable and biomedical production. The yield is 20 to 30 times that of a conventional field, variety dependent, and the crop is not under weather distress as the environment can be remotely controlled. Lufa Farms, headquartered in Montreal, started the rooftop movement now popular around the world. But it was Vancouver that got folks thinking about filling the space on every floor with food all the way to the roof. Canada started thinking about going vertical.

As cities develop, food policies and municipalities enacted bylaws restricting chemical usage, the natural progression has been to move farms in and up. Touring the Delta area of British Columbia and the Golden Horseshoe in Ontario are jaw-dropping farming experiences. The agricultural output is staggering.

Vertical farming goes a little further and takes those huge flat areas often seen in greenhouses and tiers them with suspending boxes that grow food, particularly leafy greens. These products are often organic, or at least chemical free, saving that production cost while responding to consumer demand.

Some of the designs I researched took advantage of the moderate climate and were glass structures that allowed for natural light. None used soil and either had a growing medium or were hydroponic. A new structure in Canada based out of Truro, Nova Scotia is a closed system based on LED lighting that was built on the premise of food that is nutrient dense, fresh to use in the culinary world, and the structure itself can be built almost anywhere.

One of the challenges in this vast nation is the development of a delivery system that can get perishable, nutrient-dense foods to rural and remote communities. Vertical farming offers a solution to these issues — and creates jobs for the local people, attracts local distributors, and makes good food affordable.

A sack of seed could feed a village and that is an important consideration as we move forward in food policy. Another area of interest for me is the biomedical component as it complements natural health and there is an assurance of purity that we cannot confirm from imported product.

Vertical farming does not threaten agriculture, but it does change it. New technologies will continue to enhance farms in Canada, secure food in urban spaces, and allow our nation to be a world leader in terms of technology and health.

Hong Kong's Skyline Farmers

The Bank of America skyscraper farm was the first in Hong Kong’s commercial district, and a critical proof of concept for Rooftop Republic

HONG KONG’S SKYLINE FARMERS

By Bonnie Tsui

March 13, 2017

It was a breezy afternoon in Hong Kong’s central business district, and the view from the roof of the Bank of America Tower, thirty-nine floors up, was especially fine—a panorama of Victoria Harbour, still misty from the previous day’s rain, bookended on either side by dizzying skyline. Andrew Tsui nodded at the billion-dollar vista—“no railings,” he said—but he was thinking of the harvest. Specifically, he was examining a bumper crop of bok choy, butter lettuce, and mustard leaf, all grown here, at one of the most prestigious business addresses in the city. Spade in hand, Tsui scraped at the electric-green moss that had begun to sprout on the sides of the black plastic grow boxes—a result, he said, of the damp sea air off the harbor. “I really like this work,” he told me, still scraping. “It’s soothing, like popping bubble wrap.” A faint breeze ruffled the lettuces.

Tsui is a local boy, born in Beijing and raised in Hong Kong. Two years ago, with Pol Fàbrega and Michelle Hong, he founded Rooftop Republic, the company behind the Bank of America farm and nineteen others around the city. Though Hong Kong now imports ninety per cent of what it eats—mostly from mainland China—Tsui will remind you that, only half a century ago, sixty per cent of the supply was homegrown. “We are not trying to go back to growing everything here—that’s impossible,” he said. “But city people are pretty vulnerable when it comes to food.” Recently, Tsui noted, concerns over safety and contamination—milk and baby formula tainted with toxic melamine; pigs illegally fed growth-enhancing asthma drugs—have driven residents to look more closely at the regional food chain. A decade ago, organic farms in Hong Kong’s rural New Territories were nearly nonexistent; now there are more than four hundred and fifty of them. Meanwhile, Hong said, demand for Rooftop Republic’s urban-farming classes and projects has spiked. “Food labelling and organic certifications may not be clear or fully transparent here, so many people have become keen to grow their own food, at least in part,” she told me.

The Bank of America skyscraper farm was the first in Hong Kong’s commercial district, and a critical proof of concept for Rooftop Republic. It is situated on a decommissioned helicopter landing pad—the “rooftop of all rooftops,” Tsui called it. When I visited, in November, he and his colleagues had just finished harvesting some Chinese vegetables, which would be trucked off to a local food bank, cooked, and packed into lunch boxes for the poor. Tsui picked a mustard leaf and handed it to me. It was bracingly peppery and spicy, with a wasabi finish—indiscernible, in other words, from mustard grown on terra firma. And this was no small accomplishment. The helipad site is windy, and when Rooftop Republic got started there it also lacked water access. Undeterred, Tsui and Fàbrega set the beds low on the roof, so they wouldn’t blow away during typhoon season, and installed pumps and an automatic irrigation system. They rotated crops with the seasons—amaranth, Chinese spinach, and sweet potatoes in summer; romaine lettuce, radishes, and kale in winter. Dedicated farmers come every one or two weeks to tend the crops. “This batch of soil—we know it now,” Hong said.

Each project that Rooftop Republic designs is equally site- and client-specific. At its farm atop Cathay Pacific’s headquarters, near Hong Kong International Airport, airline employees perform the labor. They choose the crops they want to grow, harvest the produce, and take it home. At the EAST Hotel, in the Tai Koo area, Rooftop Republic helped set up a small garden on a long, skinny deck near the fourth-floor swimming pool. The week I visited, the hotel employees had just harvested their first okra, which would go into the restaurant’s vegetarian curries, and green beans and peppers were beginning to sprout. Jonathan Wallace, EAST’s manager, said there are plans to expand. “Our rooftop doesn’t do much outside of housing a window-cleaning gondola,” he told me. Indeed, outdoor space all around Hong Kong tends to be underutilized. Aside from satellite dishes, cooling vents, and the odd deck, many rooftops are empty.

This has left Rooftop Republic with plenty of room to grow. In the past two years, the company has averaged one new farm a month; by the end of 2017, it expects to have set up about fifty farms and transformed forty-five thousand square feet of skyline into urban farmland. And its influence goes beyond Hong Kong. Recently, the city of Seoul invited the group to an agricultural conference; Tsui and Fàbrega are also consulting with organizations in Beijing and Singapore. Their priority now is to train more personnel, including through a certification course created jointly with an N.G.O. called Silence, which focusses on the hearing-impaired. “We’re not short on weekend farmers, but we need to find more skilled full-time farmers,” Tsui told me. “At the same time, there’s no shortage of disadvantaged people in Hong Kong.” It’s a stabilizing thing to create that workforce, he said. And the rooftops could soon need them.

Bonnie Tsui is the author of “American Chinatown.” She is writing a book about swimming for Algonquin.

A rooftop farm at the Hong Kong Fringe Club, in Central District.PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY ROOFTOP REPUBLIC / THE HONG KONG FRINGE CLUB

Two Ranchi Women Turn Rooftops Into Organic Farm

Two Ranchi Women Turn Rooftops Into Organic Farm

TNN | Mar 11, 2017, 06.00 AM IST

Ranchi: Fifty-year-old Shobha Kumari doesn't need to visit the market to buy vegetables anymore. All she does is climb up to her terrace and pick some.

Krishna Singh's (49) friends go green with envy every time they see her terrace while her own heart swells with pride.

Green love is blooming on the rooftops of these two residents of Ranchi, who have taken out time from their daily life to grow lush, fresh and pesticide-free vegetables, fruits and flowers on the rooftops of their houses.

The urban terrace gardens not only cut a pretty picture but does its bit in conserving nature and supplying healthy produce that goes into the dishes prepared in these two homes.

Both Shobha, a resident of Nivaranpur near Main Road Overbridge, and Krishna (49), who lives in Friends Colony in Pandra, use vermi-compost and cow dung as manure to grow vegetables, fruits and flowers in pots, drums and cement sacs.

Every day, they devote two hours to nurturing the plants with much love and care, the job acting as the perfect stress-buster for them. And as they watch the saplings grow, all tall, lush and beautiful, their joy knows no bound.

"A few days ago, I had grown 2.5kg beans. This apart, my terrace has tomatoes, chillies, brinjals, coriander leaves and other vegetables. I also grow oranges, guavas, litchis, pomegranates and strawberries, besides roses and marigold. I have altogether 250 pots," said a very proud Shobha, whose rooftop garden sprawls across 2,500sqft.

The widow with a green thumb consciously chose to grow her own veggies in 2012 after realising that vegetables available in the market were not only expensive but also harmful because of use of pesticides.

"We cannot ignore the health hazards just like this. Nothing can beat the feeling of seeing my family members relishing my labour of love when they eat dishes prepared with the vegetables I have grown. It's really amazing to nurture these plants. In return, I get satisfaction," Shobha said.

Krishna's rooftop garden spreads across 5,000sqft, which she had reared with equal love and dedication for the past eight years.

"Earlier I used to grow flowers like roses, sunflowers and petunia in small pots. Then, I developed a passion for growing veggies in cement sacs. For manure I stick to cow dung, karanj and neem twigs to protect the plants from insects. I felt elated after preparing vegetables picked from my own garden. Thereafter, there was no looking back," she said.

This 49-year-old is a proud owner of 300 pots, bearing tomatoes, coriander, brinjal, methi, green chillies and radish. "My three children are based outside now, but I click photographs of my rooftop garden and send them. I am excited about preparing vegetable dishes for them when they will come in December. The vegetables are grown without use of pesticides, they are very natural and healthy," the homemaker, whose husband works in AIR, Ranchi, said.

Every day, she uses some vegetables like tomatoes in cooking. "I had grown 10kg tomatoes, one kg coriander leaves and 10kg green onions, which I distributed among my friends," she added, proudly.

Krishna starts growing the vegetables from October every year. "These are winter veggies, which will continue to blossom till March. This is the perfect time for gardening," she signed off.

Urban Farming Insider: Understanding Organic Hydroponics With Tinia Pina

Tinia Pina is the founder and CEO of Renuble, a company started in 2011 that develops hydroponic fertilizer 100% derived from organic food waste inputs.

Renuble helps hydroponic growers increase yields with a wide variety of urban farming crops grown hydroponically in large metropolitan areas like New York City, where Renuble is based.

Urban Farming Insider: Understanding Organic Hydroponics With Tinia Pina

Tinia Pina is the founder and CEO of Renuble, a company started in 2011 that develops hydroponic fertilizer 100% derived from organic food waste inputs.

Renuble helps hydroponic growers increase yields with a wide variety of urban farming crops grown hydroponically in large metropolitan areas like New York City, where Renuble is based.

We interviewed Tinia to discuss:

- the basics of organic hydroponic fertilizer for beginning urban farmers

- some brand names she hears often for lighting, growing medium, common urban farming products

- and more!

___

Introduction

UV: Can you start off by talking about Re-Nuble and how it started? What's your mission?

Tinia: I founded Re-Nuble in 2011, the whole premise behind that was to try to increase access to more nutritious options, primarily in cities, because I saw that's were the trend was as far as macroeconomics of people migrating towards (cities).

So, how can we make food, especially nutrient dense food, more affordable, and by doing that, making use of the abundant food waste in New York City and more efficiently serve the needs of food production.

My vision to achieve that was re-purpose or up-cycle the reclaimed nutrients from food waste and at the time New York City was spending 33 million dollars (per year) to export its food waste.

We thought that by manufacturing value added, organic liquid fertilizers, primarily within the hydroponic industry, because there was definitely, and still is, a demand to grow with organic inputs, it is challenging... but we've proven that you can achieve comparable grow results.

Granted, the nutrient management side still takes a bit of a learning curve to adopt, before (using this type of fertilizer is really seamless.

So the goal is to indirectly increase food production in cities so that we can cover the crisis of food with more supply.

UV: You mentioned the learning curve for hydroponics, can you talk about what that entails? Obviously, with the company being around since 2011, you have a really good perspective on how hydroponics have been trending in the urban farming setting since then. What's your perspective on that?

Tinia: We started in 2011 with a different business model, we pivoted into hydroponics because the problem was more prevalent with using organic fertilizer and meeting that demand, (the pivot was) only as of 2015.

The challenge with organics or anything that's biologically derived is because it's so natural, you can't have the precision that you have with a synthetic fertilizer where it's already in its ionic form and readily available to the plant.

(With synthetic fertilizer), you know exactly to the parts per million what ionic nitrogen or phosphate or mineral is available to the plant.

With biologicals, a lot of the decomposed matter, for example, in ours, we have organic certified produce waste, that decomposed matter still goes through a degradation when it is subjected to a hydroponic reservoir (unlike synthetic fertilizer).

So (biological fertilizer) is still decomposing when you're in a hydroponic reservoir, and that lessens the ability to have precision and know exactly how much your pH or EC will be, especially within the first 1 or 2 weeks of growing, and that tends to stabilize after that.

UV: When you say "the first 1 to 2 weeks" what is that 1-2 weeks referring to? Is it to after application of the fertilizer?

Tinia: When the fertilizer is bottled, we're guaranteeing, a six month shelf life, so it is pH stable (pre application), and then when you dilute it in your hydroponic reservoir, it does go through a natural decomposition because the microbes are active again, so to answer your question, the pH and EC swing after application into the hydroponic solution due to microbe activity, so you're unable to say "you can expect with certainty a pH of 6.5 within the first 2 weeks simply because biological fertilizer has to normalize.

We've shown historically, it's at that two week mark, that your EC swings, anywhere from .8 to 3, then tends to normalize, and that's only for hydroponic reservoirs.

In soil, because you have the soil and you have a medium that diffuses, the microbes act differently in the soil medium, just like they would in rockwool or similarly in coco coir. How the organic fertilizers act in those substrates has less effect on your EC and your pH.

UV: You touched on a ballpark EC range, what is a range for pH (for hydroponic mediums)? Does it depend on the crops you're growing?

Tinia: So what we do with our product line, we have an Away We Grow, which is a grow formula, True Bloom, for flowering, and fruiting crop formula, and a supplement which does really well with microgreens but it's a supplement at the end of the day.

So we advise (pH level in hydroponics) on a benchmark. With biologicals (fertilizers) you aren't able read EC technically because there are no mineral salts, but we show based on our own trials that EC of 1.8 for butterhead leafy lettuce for example, it will be optimal to maintain that EC for the 4 or 5 week duration that you're actually cultivating it for.

Then we prescribe a pH range (only) if you were using synthetics.

UV: To clarify, the reason why you can generate this data on EC and others can't is because your essentially doing some type of simulation? Is that a fair way to say how you derive your EC benchmark of 1.8? You essentially said with the EC that you can't technically measure it, then you said is you guys do project it for the edification of the customer. What are you doing that the customer can't do as far as simulating EC?

Tinia: The customer should already be measuring their hydroponic solution for pH and EC, the only big difference is, say (For example), you often have a pH stick that also measures for EC, if you were to subject it to a reservoir that has our nutrients in it (organic fertilizer), it's going to "dial" or measure an EC value, but, there really is no salts that are in the solution, so the (reading) isn't accurate.

So what we do is project the EC so that we can tell you what to look our for, but (at first), there isn't a true measurement because technically there's no salt's in there at the end of the day.

UV: SO this at the end of the day, is a very technical aspect of hydroponic nutrients?

Tinia: Yes. With organics in general, it can be grown just as effective, as far as leaf size and harvest weight, it can take a little more time to get the same harvest weight compared to synthetics, and that's expected because it's a slower uptake process.

But you can grow with organic fertilizer just as you can grow with synthetic fertilizer. This same reason is why Re-Nuble has gotten so much interest - people want to have a more viable alternative to synthetic hydroponic fertilizer, it's the same with food and medicine, it speaks to the same cause (to not rely on synthetics).

UV: For people who are looking at the unit economics, cost and benefit analysis, maybe they're thinking about starting their own urban farming hydroponic operation, what do you look at when you're looking at the cost of say, a biologic fertilizer compared to say, a synthetic one?

When crops are grown and harvested, what do you typically see as the mark-up for the organic hydroponic produce you're typically helping your customers grow?

Tinia: We've seen to date that just organic or natural branded crops tend to command a ~44% pricing premium.

That mainly pertains to metropolitan areas, we've done less testing with rural, traditional farmland areas.

Now, (on the unit cost side), you will notice that with organic hydroponics you will typically need more applied fertilizer than with synthetic fertilizer.

As I mentioned earlier, this is because synthetic fertilizers already provide the nutrients in ionic form, which just means it's readily available for the plant to pick up, whereas with organics, there's still a requirement for the plant to convert (the organic waste based fertilizer) into a form that can be picked up.

So what that essentially means is that you will need more organic fertilizer to get to the same needed concentration, compared to synthetic fertilizer.

I typically estimate you will need 20% more of the organic fertilizer than with synthetics, but if you're selling the (organic) urban farmed produce, and you can sell it higher, it's typically worth the cost!

UV: So you're applying 20% more, on a unit basis does organic hydroponic fertilizer cost the same amount as synthetic hydroponic fertilizer? How does it compare?

Tinia: It depends on the production scale, the water, the temperature. It does become technical to answer that question because all of these variables, water, temperature, the crop type sometimes, the moisture, the air in the actual grow space, can slightly increase or slightly decrease the nutrient consumption.

So I can't give a (generalized) baseline for unit cost unfortunately.

UV: Another thing I get asked about is, especially for setting up a hydroponic system, is regarding the most commonly used / popular brands, I'm not asking you to talk as much about the fertilizer but when you're interacting with customers, what are some of the common names you see them using for the actual hydroponic system, for the tanks, for lighting, what are some of the popular names that you're hearing about more often?

Tinia: What I'm hearing from people, anywhere in between New York City, Florida, DC, and a couple people on the west coast, for lighting I've heard Lumigrow. They tend to be a popular brand on the commercial side as well as hobbyists.

For the organic base (hydroponic nutrient fertilizer / "grow formula"), depending on what you're growing, people have said Pure Blend, which is part of Botanicare, that's a brand that we directly compete with, and we've shown better yields for some crops for Botanicare, the main differentiation between Runuble and Botanicare is that Renuble has 100% organic certified inputs whereas they say they have an organic base but they do incorporate synthetics into their (fertilizer) formulation.

On the medium side, I hear Growdan (rockwool cubes) a lot, with hydroponics, surprisingly users taking a blend of perlite and mixing it with cocoa coir, kind of a hybrid set up, on the soil side, what's been popular is Batch 64, depending on what your growing, they have Batch 64 and then Waste Farmers.

The reason why I'm speaking (about) these brands is because they (the brands above) are for people interested in sustainable grows, and those that have more of an organic alignment.

UV: I like to finish up with some rapid fire questions. What's a company in the urban farming space that your excited about / that you think is onto something, that you've been following, maybe a CEO that you've been following in the space?

Tinia: One is called Farm.One. Instead of the retrofitted shipping containers they take microfarms and they provide specialized growing services but focusing on really exotic herbs. So they're really taking an angle of (growing for) culinary art to a whole other level and not just producing your typical commodity crop.

UV: The next question would be what's your favorite fruit or vegetable?

Tinia: Strawberries.

UV: What's your favorite book relating to urban farming? I know that's specific and there may not be that many books, so if you don't have an idea for that what's one of your favorite books in general, one that is most gifted or that you most recommend.

Tinia: I have quite a few! There are books on my bookshelf that I haven't even read yet but I'm wanting to. But answer your question, "The Vertical Farm", by Dickson Despommier, which is cliche now.

UV: The last question is, what's something you disagree with or think there's a misconception about in the urban farming industry or hydroponic industry that is generally accepted as being true?

Tinia: It's less of the hydroponic industry but more of the agricultural industry in general, but I'm not sure if you know, but this April 17th, anything hydroponically or aquaponically grown that wants to obtain organic certification is being voted as to whether it can obtain that certification.

So the contention that I want to bring up is that hydroponics and aquaponics, anything in the controlled environment industry, can be successfully synergistic with conventional ag. I think right now, because there is a market, it does impact a lot of people's bottom line. If they open up the organic certification process, I think a lot of people think they have to be competitive and contentious but they can very much complement each other (conventionally organic grown produce vs controlled environment organic agriculture) very much.

Thanks Tinia!

Are Indoor Farms The Next Step In The Evolution of Agriculture?

You’ve probably heard of farm-to-table, or even farm-to-fork, agricultural movements that emphasize the connection between producers and consumers. But what about factory farm-to-table?

Are Indoor Farms The Next Step In The Evolution of Agriculture?

SPECIAL TO THE JAPAN TIMES

MAR 10, 2017

You’ve probably heard of farm-to-table, or even farm-to-fork, agricultural movements that emphasize the connection between producers and consumers. But what about factory farm-to-table?

Spread, a giant factory farm that grows lettuce in Kameoka, Kyoto Prefecture, is just one of more than 200 “plant factories” in Japan capable of harvesting 20,000 heads of lettuce every day. Their lettuce, which includes frilly and pleated varieties, is grown in a totally sterile environment: There’s no soil or sunlight, no wind nor rain.