Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

'Pioneering New Frontiers': Fuqua Alumni Advise 'Farm-At-Your-Table' Food Truck

Photo by Special to The Chronicle | The Chronicle

'Pioneering New Frontiers': Fuqua Alumni Advise 'Farm-At-Your-Table' Food Truck

By Noah Michaud | 09/18/2017

If you stroll down West Geer Street on a Wednesday afternoon, you may be surprised to find a farm parked in front of you.

Meet the Farmery, which Ankur Sanghi and Ryan Graven—both Fuqua ’14—recently adopted. The brainchild of CEO Ben Greene, the Farmery is a multicomponent food truck and container farm model. It cooks with what it grows—whether it is exotic mushrooms, salad greens or herbs—every morning. Greene mentioned that they even had a mini-farm, the “CropBox,” behind a portable Airstream kitchen downtown, which they hope to reinstate soon.

“The model is very cool. It checks all the boxes,” said Sanghi, an advisor to the company. “It’s a much more efficient way of enjoying food. Instead of farm-to-table, farm-at-your-table.”

The Farmery brings to that table a cuisine they call “superfood fusion”—a mix of hearty salads, gourmet wraps, bowls and melts that highlight the fresh yet unique ingredients they grow. Beyond the East by West Bowl—Sanghi’s personal favorite—customers can also taste plates like the Earth First flatbread or the Do the Chimi Chicken Melt, which features their house-made chimichurri sauce. And the best part?

“All of our food is 100 percent free of preservatives,” Greene said.

In addition, all production is 100 percent free of chemicals and based off of “organic nutrients and growing substrates,” as stated on the website. Additionally, a 40-foot indoor farm only uses as much energy as a “large produce cooler” as a result of its hybridized system of vertical farming, aquaponics—fish farming and hydroponics—and specialized LEDs.

However, the Farmery goes beyond the local endeavors of healthy food and resourceful agricultural practices. Greene and his team are also looking to extend the Farmery’s influence far beyond Durham and the Research Triangle by constructing indoor farms for other clients.

Greene also spoke of his excitement about collaborating with North Carolina State University to perform studies testing the current production capacity of his model, as well as about traveling to Costa Rica in the future to introduce the model internationally.

The company's decisions are influenced by goals to fulfill its self-proclaimed mission of “social and environmental responsibility,” or “how [we] can disrupt that distribution system," as Sanghi said.

“[We want] to refine the fast-casual type restaurant on the restaurant end, and on the business end, become a new standard for production and consumption,” Greene said.

In the meantime, Greene is satisfied with the quick progress achieved so far.

“[We’re] executing a really good system, doing something new or doing something well that hasn’t been done well before," he said. "We’re pioneering new frontiers.”

Sudbury Container Farm Producing Smart Yields For Producers

Smart Greens was founded by business partners Eric Amyot and Eric Bergeron in Cornwall in 2014. They started out with a refurbished shipping container, using hydroponics and LED lighting to create a climate-controlled environment that reduces growing hazards, such as pests and harsh weather. Eventually, they improved the design, adapted the technology, and came up with their current model.

Sudbury Container Farm Producing Smart Yields For Producers

Smart Greens-Sudbury is a new container farm that’s producing 100 pounds of kale a week. Its owners believe indoor, contained farming is the future of food production.

Steph Lanteigne harvests kale from his container farm in the Sudbury bedroom community of Chelmsford. (Lindsay Kelly photo)

At the Sudbury farmers market on a recent Thursday afternoon, Erin Rowe and Steph Lanteigne unloaded their usual 75 bags of freshly picked kale, hoping to find buyers for their harvest. Just 90 minutes later, they were completely sold out.

The crisp, leafy green has incited a fervent fanbase amongst the market’s clientele since they began cultivating the crop at their Smart Greens-Sudbury indoor hydroponic farm just outside of Sudbury in April.

“The response has been fantastic,” Rowe said. “It’s modern farming. I believe that it’s the future, especially Northern farming.”

Smart Greens was founded by business partners Eric Amyot and Eric Bergeron in Cornwall in 2014. They started out with a refurbished shipping container, using hydroponics and LED lighting to create a climate-controlled environment that reduces growing hazards, such as pests and harsh weather. Eventually, they improved the design, adapted the technology, and came up with their current model.

The Smart Greens-Sudbury container farm resembles a shipping container, but is specifically tailored to farming, using four-inch-thick structural insulated panels designd for walk-in coolers. (Lindsay Kelly photo)

Plants are cultivated from seed and then transplanted into vertical growing towers, which allows the farmers to grow up to 4,000 plants in just 400 square feet of space. The amount of water, nutrients, and light are all controlled by a programmable computerized system.

Several crops have been tested by the founders, but for Rowe and Lanteigne, kale is proving to be a hardy, quick-growing cultivar that’s high in demand. They can harvest the leaves from one plant, which regrow at a quick pace, multiple times for up to three months before a new seed has to be planted.

“What we’re finding is kale is a really unique product,” Lanteigne said. “It’s unlike anything else that’s on the market. The fact that it’s hydroponic means that it grows very quickly and it doesn’t get that bitterness, the stalkiness that you get with regular kale.”

The couple aren’t farmers by training — Rowe is a teacher, while Lanteigne has degrees in biology and applied linguistics — but they came across the idea for container farming while contemplating a return home to Canada after a 12-year stint teaching English in South Korea.

Searching out a new challenge that would let them spend more time with their four-year-old daughter, Indie, Lanteigne came upon the Smart Greens website and started an 18-month conversation with the founders to determine if it was the right move.

They bought some property, sight unseen, in the Sudbury bedroom community of Chelmsford, and got their farm on April 19. Smart Greens-Sudbury became one of six container farms in the Smart Greens network and the first in Northern Ontario.

Within eight weeks, the farm was producing its first kale. That quick turnaround, from inception to first harvest, is one of the most attractive facets of the system. And it keeps producing 52 weeks of the year, regardless of growing conditions.

“When we’re monocropping for kale, depending on how good of a job we do that week, we can get between 100 and 150 pounds a week perpetually,” Lanteigne said.

He believes there’s ample opportunity for growth in the sector, although the technology isn’t quite ready to roll out on a large scale, at least for the average farmer. A Smart Greens farm requires a huge investment — in both money and time — although it does come with full support from the parent company, including help from a master grower, technological advice and marketing assistance.

“Absolutely, the hydro bill is expensive. It's probably our number one operating cost; there's no getting around that,” Lanteigne said.

“But for every one per cent of energy cost that I increase, I'm getting one per cent increase in biomass. So, for us, the hydro costs are significantly offset by the fact that these plants grow that quickly.”

Lanteigne, in particular, has spent long days fine-tuning the levels of nutrients, water and lighting in order to find the perfect mix that will return the best yields. And yet, there’s still room for human error.

Early on in the process, one day before a harvest, the entire crop of kale nearly failed because the plants weren’t getting water: they had forgotten to turn on the valve that would deliver the water to the plants, something Lanteigne calls a “terrifying” lesson.

Since then, it’s been mostly smooth sailing. In addition to regularly selling out of their harvest at the farmers market, the couple has a number of restaurants on their client list, which is growing. They’ve even turned an early crop of basil into pesto. Demand for their kale is increasing, and there are already plans in the works for expansion.

“Our plan for the next six months to a year is farm number two: the identical system to this one, but with little tweaks here and there to make it a little bit more efficient,” Lanteigne said.

“In three to five years, we want to use the same technology, but in a warehouse.”

As they increase their output, the couple expects to hire additional staff to help with planting and harvesting, all of which is done by hand.

Financing for the second farm is already in place, said Lanteigne, who expects it to arrive in late October or early November — when other producers are shutting down for the season, they’ll actually be ramping up production and doubling their output, although which crop they’ll take on this time around is still up for debate.

“Spinach is on the table, lettuce is on the table, and quite a few restaurants want us to grow basil and mint,” Lanteigne said. “It’s a balancing act between what we can grow together, what we should be growing commercially, in terms of finances, and what people want.”

This High-Tech Vertical Farm Promises Whole Foods Quality at Walmart Prices

Before stepping into Plenty Inc.’s indoor farm on the banks of the San Francisco Bay, make sure you’re wearing pants and closed-toe shoes. Heels aren’t allowed. If you have long hair, you should probably tie it back.

Working in the Map Room, one of Plenty’s R&D rooms in South San Francisco.

PHOTOGRAPHER: JUSTIN KANEPS FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

This High-Tech Vertical Farm Promises Whole Foods Quality at Walmart Prices

SoftBank-backed Plenty is out to build massive indoor farms on the outskirts of every major city on Earth.

By Selina Wang | September 6, 2017

Before stepping into Plenty Inc.’s indoor farm on the banks of the San Francisco Bay, make sure you’re wearing pants and closed-toe shoes. Heels aren’t allowed. If you have long hair, you should probably tie it back.

Your first stop is the cleaning room. Open the door and air will whoosh behind you, removing stray dust and contaminants as the door slams shut. Slide into a white bodysuit, pull on disposable shoe covers, and don a pair of glasses with colored lenses. Wash your hands in the sink before slipping on food-safety gloves. Step into a shallow pool of clear, sterilized liquid, then open the door to what the company calls its indoor growing room, where another air bath eliminates any stray particles that collected in the cleaning room.

The growing room looks like a strange forest, with pink and purple LEDs illuminating 20-foot-tall towers of leafy vegetables that stretch as far as you can see. It smells like a forest, too, but there’s no damp earth or moss. The plants are growing sideways out of the columns, which bloom with Celtic crunch lettuce, red oak kale, sweet summer basil, and 15 other heirloom munchables. The 50,000-square-foot room, a little more than an acre, can produce some 2 million pounds of lettuce a year.

Step closer to the veggie columns, and you’ll spot one of the roughly 7,500 infrared cameras or 35,000 sensors hidden among the leaves. The sensors monitor the room’s temperature, humidity, and level of carbon dioxide, while the cameras record the plants’ growing phases. The data stream to Plenty’s botanists and artificial intelligence experts, who regularly tweak the environment to increase the farm’s productivity and enhance the food’s taste. Step even closer to the produce, and you may see a ladybug or two. They’re there to eat any pests that somehow make it past the cleaning room. “They work for free so we don’t have to eat pesticides,” says Matt Barnard, Plenty’s chief executive officer.

Barnard, 44, grew up on a 160-acre apple and cherry orchard in bucolic Door County, Wis., a place that attracts a steady stream of fruit-picking tourists. Now he and his four-year-old startup aim to radically change how we grow and eat produce. The world’s supply of fruits and vegetables falls 22 percent short of global nutritional needs, according to public-health researchers at Emory University, and that shortfall is expected to worsen. While the field is littered with the remains of companies that tried to narrow the gap over the past few years, Plenty seems the most promising of any so far, for two reasons. First is its technology, which vastly increases its farming efficiency—and, early tasters say, the quality of its food—relative to traditional farms and its venture-backed rivals. Second, but not least, is the $200 million it collected in July from Japanese telecom giant SoftBank Group, the largest agriculture technology investment in history.

Anthony Secviar, chef and member of Plenty’s culinary council.

PHOTOGRAPHER: JUSTIN KANEPS FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

With the backing of SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son, Plenty has the capital and connections to accelerate its endgame: building massive indoor farms on the outskirts of every major city on Earth, some 500 in all. In that world, food could go from farm to table in hours rather than days or weeks. Barnard says he’s been meeting with officials from some 15 governments on four continents, as well as executives from Wal-Mart Stores Inc. and Amazon.com Inc., while he plans his expansion. (Bezos Expeditions, the Amazon CEO’s personal venture fund, has also invested.) He intends to open farms abroad next year; this first one, in the Bay Area, is on track to begin making deliveries to San Francisco grocers by the end of 2017. “We’re giving people food that tastes better and is better for them,” Barnard says. He says that a lot.

Plenty acknowledges that its model is only part of the solution to the global nutrition gap, that other novel methods and conventional farming will still be needed. Barnard is careful not to frame his crusade in opposition to anyone, including the industrial farms and complex supply chain he’s trying to circumvent. He’s focused on proving that growing rooms such as the one in South San Francisco can reliably deliver Whole Foods quality at Walmart prices. Even with $200 million in hand, it won’t be easy. “You’re talking about seriously scaling,” says Sonny Ramaswamy, director of the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the investment arm of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. “The question then becomes, are things going to fall apart? Are you going to be able to maintain quality control?”

The idea of growing food indoors in unlikely places such as warehouses and rooftops has been hyped for decades. It presents a compelling solution to a series of intractable problems, including water shortages, the scarcity of arable land, and a farming population that’s graying as young people eschew the agriculture industry in greater numbers. It also promises to reduce the absurd waste built into international grocery routes. The U.S. imports some 35 percent of fruits and vegetables, according to Bain & Co., and even leafy greens, most of which are produced in California or Arizona, travel an average of 2,000 miles before reaching a retailer. In other words, vegetables that are going to be appealing and edible for two weeks or less spend an awful lot of that time in transit.

So far, though, vertical farms haven’t been able to break through. Over the past few years, early leaders in the field, including PodPonics in Atlanta, FarmedHere in Chicago, and Local Garden in Vancouver have shut down. Some had design issues, while others started too early, when hardware costs were much higher. Gotham Greens in Brooklyn, N.Y., and AeroFarms in Newark, N.J., look promising, but they haven’t raised comparable cash hoards or outlined similarly ambitious plans.

While more than one of these companies was felled by a lack of expertise in either farming or finance, Barnard’s unusual path to his Bay Area warehouse makes him especially suited for the project. He chose a different life than the orchard, frustrated with the degree to which his life could be upended by an unexpected freeze or a broken-down tractor-trailer. Eventually he became a telecommunications executive, then a partner at a private equity firm. In 2007, two decades into his white-collar life, he started his own company, one that concentrated on investing in technologies to treat and conserve water. After an investor suggested he consider putting money into vertical farming, Barnard began to research the subject and quickly found himself obsessed with shortages of food and arable land. “The length of the supply chain, the time and distance it takes,” he says, meant “we were throwing away half of the calories we grow.” He spent months chatting with farmers, distributors, grocers, and, eventually, Nate Storey.

Plenty co-founders Matt Barnard, chief executive officer, and Nate Storey, chief science officer.

PHOTOGRAPHER: JUSTIN KANEPS FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

The grandson of Montana ranchers, 36-year-old Storey spent much of his childhood planting and tending gardens with his six siblings. Their Air Force dad, who eventually retired as a lieutenant colonel, moved them to another base every few years, and the family gardened to save money on groceries. “I was always interested in ranching and family legacy but frustrated on how to do it,” Storey says. “If you’re an 18-year-old kid and you want to farm or ranch, most can’t raise $3 million to buy a farm or a ranch.”

A decade ago, as a student at the University of Wyoming, he learned about the same industry-level inefficiencies Barnard observed. He began experimenting with vertical farming for his doctoral dissertation in agronomy and crop science, and in 2009 patented a growing tower that would pack the plants more densely than other designs. He spent $13,000, then a sizable chunk of his life savings, to buy materials for the towers and started building them in a nearby garage. By the time he met Barnard in 2013, he’d sold a few thousand to hobbyist farmers and the odd commercial grower.

Storey became Barnard’s co-founder and Plenty’s chief science officer, splitting his time between Wyoming and San Francisco. Together they made Storey’s designs bigger, more efficient, and more readily automated. By 2014 they were ready to start building the farm.

Most vertical farms grow plants on horizontal shelves stacked like a tall dresser. Plenty uses tall poles from which the plants jut out horizontally. The poles are lined up about 4 inches from one another, allowing crops to grow so densely they look like a solid wall. Plenty’s setups don’t use any soil. Instead, nutrients and water are fed into the top of the poles, and gravity does much of the rest of the work. Without horizontal shelves, excess heat from the grow lights rises naturally to vents in the ceiling. “Because we work with physics, not against it, we save a lot of money,” Barnard says.

Water, too. Excess drips to the bottom of the plant towers and collects in a recyclable indoor stream, and a dehumidifier system captures the condensation produced from the cooling hardware, along with moisture released into the air by plants as they grow. All that accumulated H₂O is filtered and fed back into the farm. All told, Plenty says, its technology can yield as much as 350 times more produce in a given area as conventional farms, with 1 percent of the water. (The next-highest claim, from AeroFarms, is as much as 130 times the land efficiency of traditional models.)

Based on readings from the tens of thousands of wireless cameras and sensors, and depending on which crop it’s dealing with, Plenty’s system adjusts the LED lights, air composition, humidity, and nutrition. Along with that hardware, the company is using software to predict when plants should get certain resources. If a plant is wilting or dehydrated, for example, the software should be able to alter its lighting or water regimen to help.

Barnard, tall and lanky with a smile that crinkles his entire face, becomes giddy when he recounts the first time Plenty built an entire growing room. “It had gone from pretty sparse to a forest in about a week,” he says. “I had never seen anything like that before.”

The $200 million investment will help Plenty put a farm in every world metro area with more than 1 million residents, about 500 in all

When he and Storey started collaborating, their plan was to sell their equipment to small growers across the country. But to make a dent in the produce gap, they realized they’d need to reproduce their model farm with consistency and speed. “If it takes you two or three years to build a facility, forget about it,” Storey says. “That’s just not a pace that’s going to have any impact.” That meant they’d have to engineer the farms themselves. And that meant two things: They’d need more than their 40 staffers, and they’d need way more money.

It wasn’t easy for Barnard to get his first meeting with Son, in March. One of Plenty’s early investors had to beg the SoftBank CEO, who allotted Barnard 15 minutes. He and the investor, David Chao of DCM Ventures, jammed one of the 20-foot grow towers into Chao’s Mercedes sedan and took off for Son’s mansion in Woodside, Calif., some 30 miles from San Francisco. Son looked bewildered as they unloaded the tower, but the meeting stretched to 45 minutes, and two weeks later they flew to Tokyo for a more official discussion in SoftBank’s boardroom. The $200 million investment, announced in late July, will help Plenty put a farm in every major metro area with more than 1 million residents, according to Barnard. He says each will have a grow room of about 100,000 square feet, twice the size of the Bay Area model, and can be constructed in under 30 days.

Cutting rainbow chard.

PHOTOGRAPHER: JUSTIN KANEPS FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

Chao says SoftBank wants “to help Plenty expand very quickly, particularly in China, Japan, and the Middle East,” which all struggle with a lack of arable land. Other places on the near-term list include Canada, Denmark, and Ireland. Plenty is also in talks with insurers and institutional investors such as pension funds to bankroll its farm-building with debt. Barnard says the farms would be able to pay off investors in three to five years, vs. 20 to 40 years for traditional farms. Think of it more like a utility, he says.

Plenty, of course, isn’t as sure a bet as Consolidated Edison Inc. or Italy’s Enel SpA. The higher costs of urban real estate, and the electricity needed to run all of the company’s equipment, cut into its efficiency gains. While it’s adapting its technology for foods including strawberries and cucumbers, the complications of tree-borne fruits and rooting crops likewise neutralize the value of its technology. And Plenty has to contend with commercial farms that have spent decades building their relationships with grocers and suppliers and a system that already offers many people extremely low prices for a much wider variety of goods. “What I haven’t seen so far in vertical farm technologies is these entities getting very far beyond greens,” says Michael Hamm, a professor of sustainable agriculture at Michigan State University. “People only eat so many greens.”

Barnard says he’s saving way more on truck fuel and other logistical costs, which account for more than one-third of the retail price of produce, than he’s spending on warehousing or power. He’s also promising that the company’s farms will require long-term labor from skilled, full-time workers with benefits. About 30 people can run the South San Francisco warehouse; future models, which will be about two to five times its size, may require several hundred apiece, he says. While robots can handle some of the harvesting, planting, and logistics, experts will oversee the crop development and grocer relationships on-site.

Entering one of Plenty’s R&D rooms in South San Francisc.

PHOTOGRAPHER: JUSTIN KANEPS FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

Retailers shouldn’t need much convincing, says Mikey Vu, a partner at Bain who studies the grocery business. “Grocers would love to get another four to five days of shelf life for leafy greens,” he says. “I think it’s an attractive proposition.”

Gourmets like Plenty’s results, too. Anthony Secviar, a former sous-chef at French Laundry, a Michelin-starred restaurant in the Napa town of Yountville, says he wasn’t expecting much when he received a box of Plenty’s produce at his home in Mountain View, Calif. The deep green of the basil and chives hit him first. Each was equally lush, crisp, flavorful, and blemish-free. “I’ve never had anything of this quality,” says Secviar, who while at French Laundry cooked with vegetables grown across the street from the restaurant. He’s now on Plenty’s culinary council and is basing his next restaurant’s menu around the startup’s heirloom vegetables. “It checks every box from a chef’s perspective: quality, appearance, texture, flavor, sustainability, price,” he says.

At the South San Francisco farm—recently certified organic—the greens are fragrant and sweet, the kale is free of store-bought bitterness, and the purple rose lettuce carries a strong kick. There’s enough spice and crunch that the veggies won’t need a ton of dressing. Although Plenty bears little resemblance to a quaint family farm, the tastes bring me back to the tiny vegetable patch my grandparents planted in my childhood backyard. It’s tough to believe these spicy mustard greens and fragrant chives have been re-created in a sterile room, without soil or sun.

News And Happenings From Tiger Corner Farms Manufacturing

News and Happenings from Tiger Corner Farms Manufacturing

We are GAP CERTIFIED

Big news: As of this month, all TCF operating farms are GAP certified, meaning we've received the USDA's stamp of approval for Good Agricultural Practices. We are thrilled for what this now allows for our container customers: more opportunities to grow and expand their farming businesses. It's a win-win for all and ensures our farms are fully compliant with the U.S. food system.

Wondering how this may apply to you? We're happy to discuss.

SC Commissioner of Agriculture visits TCF

We were honored to have South Carolina's Commissioner of Agriculture, Hugh Weathers, make a recent visit to our farms. Food supply in our home state is a cause near and dear to our hearts, so it was our privilege to share our work with him and discuss these issues while showing him what our containers are all about.

#TCFLIFE

Who's feeling lush and leafy? If you're raising your hand, you're in delicious company with this bibb lettuce about ready for harvest. It was a busy month with containers moving out and in on site, and the crane game was strong. Finally, we sent intern Alex off with a (pizza) toast for a job well done and an excellent final presentation on what he's learned and accomplished with us this summer. We're excited to have him back again in the fall for his Citadel senior project. Just another solid month of the #TCFlife that you can follow onour Instagram.

This Company Is Developing Pop-Up Urban Farms for City Streets

Exsilio Oy has responded to this challenge with its EkoFARMER, a small, self-contained farming chamber containing all the necessary seeds (from greens to herbs to plants), as well as adjustment mechanisms, meaning that output will not be affected by seasonal or climate factors.

This Company Is Developing Pop-Up Urban Farms for City Streets

Exsilio Oy is making a big splash in community gardening efforts with its EkoFARMER. The little greenhouse in a box is a very creative solution to producing high yield in urban areas with limited space and limited resources.

September, 10th 2017

EkoFARMER Farming ChamberExsilio Oy

From the East Coast to the West Coast, the United States has been seeing in the last decade a kind of community garden renaissance. More people are demanding better access to fresh, organic produce, without paying the high prices associated with organic food in the US—there are advocates for and against it on both sides, and little agreement about whether it is too expensive or if the high prices are justified. The reality is, though, that not all of us have a green thumb or the time and resources to know where to begin.

Source: Exsilio Oy

Exsilio Oy has responded to this challenge with its EkoFARMER, a small, self-contained farming chamber containing all the necessary seeds (from greens to herbs to plants), as well as adjustment mechanisms, meaning that output will not be affected by seasonal or climate factors. The Finland-based company has even created an interactive video with 3D models explaining the various parts and how they all work together. The boxes use house farming technology which controls the environment and helps to increase yield.

Source: Exsilio Oy

Fighting the Tide of Food Deserts

Green activists and members of the community are combining their efforts to respond to the main two issues driving the community garden revival: price and access. For some in the community, the need is more urgent, as urban deserts—impoverished areas which face critical issues related to accessing affordable and nutritious feed—have been appearing in virtually every city in the United States in the last two decades. The issue is of such growing concern that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) officially identified the term back in 2011, creating a Food Access Research Atlas and other maps which list essential data related to charting the problem, such as population demographics and proximity to supermarkets.

Source: American Nutrition Association

Michigan State University Assistant Professor of Community, Agriculture, Recreation and Resources Studies Phil Howard—one of the most vocal academic voices about the impact of food deserts in America explains the phenomenon of food deserts:

“The term ‘food desert’ kind of implies it's a natural phenomenon...What’s really been happening in some areas described as ‘food deserts’ is that they used to have supermarkets or chain grocery stores, and those stores have been shut down as they've been opening new stores in the suburbs. It's not a natural phenomenon at all.”

A company with a strong Exsilio Oy has begun a number of initiatives with businesses and is partnering with the community through its micro-entrepreneur and business co-partnering projects and is committed to making a difference.

Howard continues: “A desert implies either there's no food, or there is food, and the reality is a lot more complicated..Often, people in [these] areas have access to a lot of food-like substances that are not very healthy. Or they may have access to [only] a few types of fresh fruit and vegetables...”

Of course, intervention and measures taken by policy makers is a key part of the process; however, the powerful initiative of urban communities will have the biggest impact. Companies like Exsilio Oy, therefore, are empowering people every day to make nutrition and wellness a high priority.

Via: Exsilio Oy, Pacific Standard, Consumer Reports

Here’s What You Need to Know About The Organic Standard Changes

Here’s What You Need to Know About The Organic Standard Changes

by Jason Arnold | Sep 7, 2017 | Business Mgt & Operations, Farm & Business Planning | 0 comments

The Organic standards could soon exclude your farm from ever being certified.

You’ve probably heard about the organic standards changing. But you might not know what’s actually happening and how it impacts your farm. Whether you’re currently an organic farmer, or if you’ve had even a fleeting thought about getting certified, changing standards can impact your ability to sell and grow great food.

In this article, we’re going to discuss what’s happening in the NOSB and USDA, and why soilless farms should have the option to get certified organic.

Here’s what’s happening

The National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) is a board of 14 people that make recommendations to the USDA regarding the organic standards – what they should be and how they should change.

Currently, the NOSB is considering a recommendation that the USDA bans hydroponic, aquaponic, aeroponic, and other container-based growing methods from the organic standards. (Currently, growers using these methods are able to receive organic certification under the USDA’s National Organic Program.)

If the USDA were to take such a recommendation, it would bar soilless farmers from ever being certified organic.

The option would be off the table – probably forever. This would put the hydroponic and aquaponic industries at a disadvantage and could even impact traditional organic farmers as well by deleting a significant portion of the organic community.

The NOSB’s upcoming recommendation will impact real farmers across the U.S.

To protect the business options of farmers and future farmers, it is critical that members of the hydroponic, aquaponic, and aeroponic community make their voices heard by the NOSB. The ultimate goal is to ensure that consumers can continue to have an ample supply of reasonably priced organic fresh produce.

How do I get involved?

There’s a lack of information regarding how hydro-, aqua-, and aeroponics work and how changed standards would impact farmers. The best way to make sure your voice is heard is to tell the NOSB how this decision will affect you and your farming business. The NOSB will take your comments into account as they prepare for a vote on October 31st.

Click here right now to make a comment.

It’s not always easy to sit down and articulate your comment, so we’ve outlined the four main issues surrounding the decision about banning growing methods. These are the primary arguments to keep organic on the table.

4 reasons to allow soilless organics

1) Soilless grown produce is robust, safe, and nutritious like consumers deserve.

The Organic label was created to signify safety, sustainability, and responsibility in food. Consumers depend on the organic label to signify that food is:

- Free of unsafe or unhealthy pesticides and fertilizers

- Resource efficient with effective cycling and recycling of inputs through the farm

- Free from harmful impacts to the air, water, and surrounding land.

- Created in humane and healthy conditions

Hydroponic and aquaponic production, like any farm, can align with these criteria.

The purpose of the Organic label is to encourage growers to grow great food, not restrict them.

One great example of how hydroponics and aquaponics support responsible resource use and nutritious food is the decrease in food miles. Hydroponic and aquaponic systems can be built indoors, enabling fresh produce to be grown close to the consumer all year round, eliminating hundreds or thousands of miles of transportation.

Locally grown fresh foods also provide better nutrients. The Harvard T.H. Chan Center for Public Health reports that “even when the highest post-harvest handling standards are met, foods grown far away spend significant time on the road, and therefore have more time to lose nutrients before reaching the marketplace.” (1)

When food is grown regionally or locally using indoor hydroponics and aquaponics, the consumer gets a richer nutritional profile, and the environment benefits from a shorter supply chain. The bottom line: hydroponics and aquaponics don’t block better food; they empower it.

2) Soilless growing contributes to the economy and strengthens food security

Modern farmers, empowered with appropriate tools and technology, are able to grow food in areas where fresh, local food has never been possible before. Doing so helps more people have access to nutritious food in previously unthinkable locations:

- Urban food deserts

- Northern latitudes

- Areas that lack abundant ground and surface water

This is helping a new generation of farmers in both urban and rural locations as they face difficult growing conditions and even more difficult economics. Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) allows more people to grow food and access markets. (3)

According to former Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack, “Urban agriculture helps strengthen the health and social fabric of communities while creating economic opportunities for farmers and neighborhoods.”

Hydroponics and aquaponics empower people to grow anywhere, all year long.

As part of the Upstart University community, you know this better than most. Your innovative spirit and commitment to your community are the beating heart of the Upstart Farmer network.

Click here to submit it this as comment to the NOSB.

3) Soilless growing doesn’t subtract the power of sun and soil; it amplifies it.

There are numerous studies about the benefits of Organic crops grown in soil with careful attention to the biological composition of the soil. Many organic farmers will claim that since we continue to learn more about the biology in organic production systems, the potential unknown benefits of producing in soil is worth excluding hydroponic and aquaponic production methods.

Unfortunately, the anti-hydroponic activists take advantage of the fact that most members of the general public do not have a degree in microbiology. By using words like “unnatural, sterile, robo-crops,” they deliberately try to to confuse the public about the realities of hydroponic or aquaponic production methods. It is up to us to set the record straight.

Indeed, studies show that Organic aquaponic and hydroponic production relies on a robust microflora in the root zone – made of the same types and numbers of bacteria and fungi that thrive in soil.

Click here to submit this as a comment to the NOSB.

4) Small farms need assistance getting to market.

Small and independently owned farms often struggle to beat the economics of the start up world and often rely on a second or third income stream to support their farm (6). The price premium that is associated with organic crops helps to support small, medium, and large farms, both locally and regionally.

Should growers using innovative approaches to produce organically be punished for doing something new?

The Organic label assists many small farmers to maintain a business.

Click here to submit this as a comment to the NOSB.

The bottom line? Organic standards should adapt to new techniques instead of dismissing them.

If the goal of the Organic label is to empower more consumers with organically grown produce, then hydroponics and aquaponics have a lot to offer. It doesn’t make sense to restrict or exclude these methods from the Organic label.

However, restriction is what will happen if farmers like you don’t speak up. Luckily, speaking up is easy; the easy way to make sure your voice is heard is to make a comment to the NOSB. The NOSB will take your comments into account as they prepare for a vote on October 15th.

Here are 4 easy way to comment:

- Go to the NOSB Organic Comments page and write a message telling the NOSB that you believe your growing methods should remain organic.

- Sign up to give a three-minute testimony at the October 24 and 26 webinars.

- Sign up to attend the Fall Meeting in person and provide in-person three-minute testimony.

- Contact your federal congressional representatives and tell them you want the NOSB to retain the organic eligibility of sustainable growing methods like aquaponics, hydroponics, and aeroponics. Click here to enter your zip code and find your representatives.

Downtown Farmer Raises Salad greens Year-Round Inside Freight Container

Harris, who sold his steel company a couple of years ago, had little experience in farming or gardening before he created Green Collar Farms , a "hydroponic vertical micro farm" located inside of a green and white re-purposed shipping container parked in a vacant lot on the city's lower West Side.

Downtown Farmer Raises Salad greens Year-Round Inside Freight Container

Updated on September 5, 2017 at 8:10 AMPosted on September 5, 2017 at 8:03 AM

GRAND RAPIDS, MI - Brian Harris is not a traditional farmer. But neither is the tender kale, spicy arugula and crispy pak choi he raises inside of a converted freight container on the edge of downtown.

Harris, who sold his steel company a couple of years ago, had little experience in farming or gardening before he created Green Collar Farms, a "hydroponic vertical micro farm" located inside of a green and white re-purposed shipping container parked in a vacant lot on the city's lower West Side.

"I'm fascinated with process and solving problems," said Harris, an engineer by training who became fascinated after a friend gave him some literature on growing vegetables indoors. "The challenge was, how do you do this indoor gardening and I could not be denied."

Harris, who also chairs the Downtown Development Authority, said he experimented with hydroponics and indoor gardening in his home's basement for several years before he got serious and bought his 350-square foot container.

The container, which once served as a refrigerated vessel for international shipping, now is lined with vertical trays in which plants are placed. Fertilized water flows through the foam in which the plants are held while ribbons of LED lamps offer just the right blend of blue and red rays to feed the plants.

The setting yields bumper crops of leafy greens and lettuces, including kale, arugula, bibb, butterhead, deer tongue, mustard, pak choi, spinach and tatsoi.

Thanks to the stress-free environment, Harris says his plants are tastier, more tender and more consistent than his field-grown competition. He's planning to add a second container to raise herbs such as basil, chives, mint, oregano and thyme.

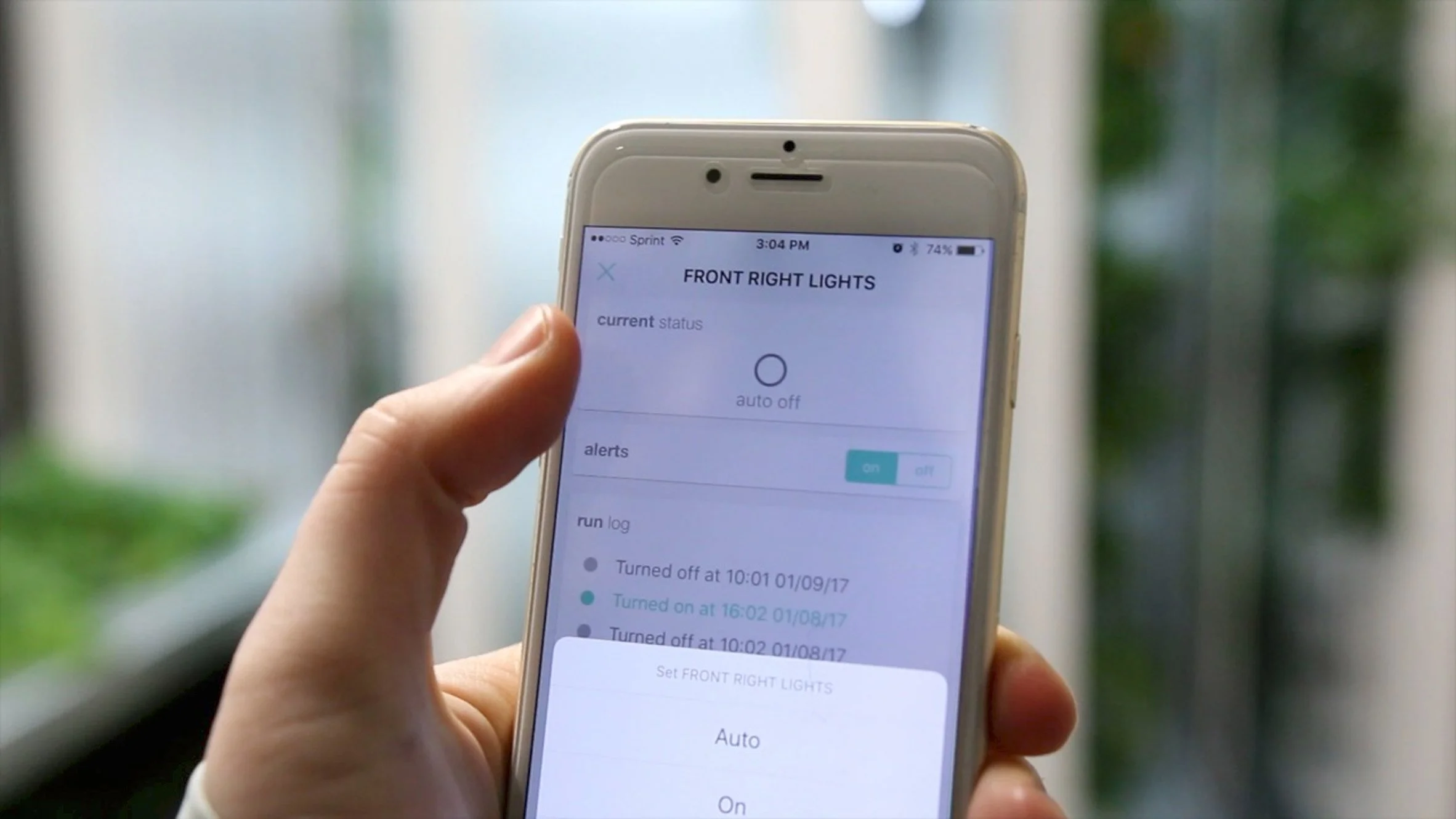

Inside the container, Harris is able to control the temperature, the humidity and the amount of light his plants are exposed to every day. The computerized controls are set up so he can control the indoor farm from his home or cell phone.

Harris germinates the plants himself from pelletized seeds he places inside water-absorbent seed plugs made of coconut husks. Placed under lights on trays, the seeds germinate within a week before they are transplanted into the vertical trays, where they get 16 hours of light every night.

The controlled environment means he does not have to treat the plans with herbicides, pesticides or fungicides. He uses just 5 percent of the water a traditional soil farmer would consume. The container also allows him to raise his crops year-round regardless of weather conditions outside.

The container, which houses white vertical trays in which he places seedlings, produces as many plants as a dirt-based farm would produce on 1.5 to 2 acres, Harris said. He estimates he will be able to produce crops on a 6-week cycle.

Harris said his $90,000 investment in container farming is being duplicated around the world as growers use "controlled environment agriculture," or CEA, to combat weather conditions that include desert heat, frozen climates, drought and flooding.

As his first crops reach maturity, Harris is now scouting for restaurants and grocers who want to stock his hyper-local and super-fresh crops.

Ultimately, Harris said he wants to find a building in the city where he can create a vertical garden in about 10,000 square feet. That will allow him to create jobs and economic opportunities in the city.

"Year-round indoor vertical farming has great potential to invigorate underutilized parts of Grand Rapids," Harris said. "We're not just trying to grow kale; we're trying to grow community vitality."

Harris also hopes Green Collar Farms will have a positive impact on young people, creating an interest in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM).

"Vertical indoor farming is a wonder to see and can spark the imaginations of young people to learn not just about STEM subjects, but also plant biology, agriculture and nutrition. This could prepare students for future careers and help them better understand where their food comes from."

The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly of Container Farms

The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly of Container Farms

Chris MichaelFollow

Chris is the CEO at Bright Agrotech — The global leaders in vertical farming equipment design and technology. Creators of ZipGrow. www.zipgrow.com

It’s time to have an honest conversation about container farming.

There’s almost nothing that rouses more cheering here at the Bright Agrotech office than seeing new farmers make their first sale.

We love seeing photos of our farmers slinging salad at a farmers’ market or selfies with their cilantro.

At the end of the day, those moments are what power us to keep doing what we do. We love it. We revel in it.

And when it doesn’t work out, we mourn just as strongly as we cheered.

When a farmer decides to quit, or when they overestimate their market, or when their equipment fails — we feel that. It’s disheartening to see someone with so much passion give up their dream.

Over the last five years, we’ve seen a lot of new growers start farms of all kinds only to shut them down a few months or a few years later. Not only is this disappointing for the farmer, but it hampers the industry through the loss of valuable farms that were helping increase access to food.

An unfortunate trend we’ve seen recently is that too many of these losses are happening in one type of farming in particular: shipping container farms.

The common killer of container farms (or any modern farm that leverages technology) is unrealistic expectations about what the tech will do for them, how much their farms can produce, and what kind of labor is required to make it all work.

Don’t forget, even technologically advanced farming is still farming!

Leveraging the modularity of containerized farms can be a very powerful way to bring better food to local communities all around the world. There’s some serious potential here and it’s exciting stuff!

However, like any new venture, modern farmers need to know what goes into being successful and what challenges they need to prepare for in the process.

To help create realistic expectations, we need to talk honestly about the potential benefits and drawbacks of shipping container farms.

In this article, we’re going to cover the main pros and cons of the (used) container form factor.

By speaking honestly about the good, the bad, and the ugly of container farms, we can help more aspiring farmers start businesses that positively impact their communities, now and in the future.

The good: What are the benefits of shipping container farms?

As of this writing, there are several hundred container farms parked in cities and backyards, parking lots and warehouses around the world.

They’ve been featured on TV, in newspapers, and by the internet’s top bloggers. Without a doubt, this type of farming has captured the interest of millions of people enchanted by the transformation of discarded containers into futuristic farms.

But does this farming form factor makes sense for farmers — those starting businesses growing and selling food?

The biggest “pros” of repurposed container farms are:

- They’re modular and easy to ship.

- They’re compact and self-contained.

- Used containers are cheap and available.

- Prices will continue to be driven down as competition increases.

Let’s dig into more details on the good side of shipping container farms.

Container farms are easy to transport

Farms built from used shipping containers are — as the name implies — easy to ship. Ideal, in fact.

The primary benefit of easy shipping is that manufacturers can set up shop where it’s cheap, then ship them directly to the farm site fully loaded and ready to grow.

There’s some serious potential there for setting up your farm quickly and starting to grow without having to worry about building a greenhouse or finding warehouse space.

Most of the benefit, however, stays with the manufacturer.

After all, why would a farmer who is establishing a farm to serve a local market need to move their farm that often? You could technically hire a crew with a crane to put in on a semi and move it across town if you felt so inclined, but why would you want to do that?

While the container farm is technically easier to move due to its form factor, we don’t advise planning a farm to be moved often.

Container farmers have a compact footprint

One benefit of growing in a container farm is that you don’t need a lot of land or a dedicated building to start.

That means modern farmers or program directors can now drop one of these behind a restaurant or in a school parking lot. In the end, the compact form opens up a lot of doors for producing food closer to where it’s consumed.

Keep in mind, however, that most container farms require a perfectly level platform to function (drainage lines need to flow in the right direction after all) and can require a cement pad.

Being able to park a farm anywhere you need food is an amazing achievement and therefore a big benefit of this form factor.

Containers are readily available

Used shipping containers are everywhere. Shipping companies have been using them for decades to ship all sorts of goods overseas, so millions of them are made.

When containers like refrigeration shipping containers break, they are often easier (and less expensive) to “retire” than to fix.

This still represents a loss for the shipping company, however, so they’re usually eager to sell whatever retired containers they can. Altogether, this makes used containers very inexpensive.

The good part for farmers is that these types of containers are cheap and available! That means for a few thousand bucks you can get the shell of your new farm to build out.

Future container farmers gain through value-based competition

Because the cost of acquiring used shipping containers is very low, there are more and more value-added companies getting into the space. The more companies there are, the more the price will decrease over time.

Obviously, a lower price point helps more aspiring farmers launch new businesses which will help to increase the supply of locally grown food around the world, which is good for everyone.

That said, investing your life savings into an inexpensive container farm may be a poor decision if you haven’t examined all the variables.

(Read on for more about the potential drawbacks of growing in a container.)

These four exciting benefits have never combined so well as in container farming. They represent an exciting area of development and accessibility to farming for people that were limited before.

The bad: What are the drawbacks of shipping container farms?

But while there are a lot of benefits to growing in a container, there are just as many drawbacks that aspiring modern farmers need to be aware of before applying for a loan or risking their 401k.

The core problem behind every drawback below is that shipping containers were not designed to grow food. And this puts growers at a disadvantage.

Because the intended purpose is absent in the fundamental design, everything required to outfit a container is a compromise.

The biggest potential drawbacks of container farms are:

- Environmental controls or lack thereof

- Structural integrity

- Antagonism between light, layout, and heat

- People and workflow issues (ergonomics)

- Misbalanced operational expense

- Low comparative output

Controlling the growing environment can be difficult in repurposed shipping containers

If managed well, there are many benefits to a controlled environment (year-round growing, more control over pests, etc.).

However, if environmental control is difficult in the facility, the same benefits become curses; conditions get out of control, humidity and heat accumulate, and pests thrive.

At any given time in an indoor farm…

- lights are generating heat.

- water is evaporating.

- plants are transpiring.

- gasses are accumulating and being exchanged.

- crop populations are fluctuating.

All the heat, humidity, and pests that result from these processes are amplified in a denser growing environment.

To make sure that controlled environment ag remains a blessing instead of a curse, environmental control must be understood and prioritized in the design of the farm.

But many container farms underestimate the complexity of controlling a growing environment consistently enough to produce a healthy crop reliably.

We’ve helped support dozens of farmers growing in repurposed containers who struggle with low productivity caused by poor environmental controls.

One farmer in particular has two containers less than a year old but have yet to reach even close to full production potential, or at least what was promised, because of humidity issues.

Insufficient lighting (constrained by heat as you’ll see below) and high humidity have resulted in low growth rates and rotting issues that are hard to compensate in the cramped space.

He’s in a very tough situation and we hate seeing this happen. Even though he’s added three new dehumidification devices, he still struggles to lower his humidity. As a result, his farm is vulnerable to disease like root rot which in a more purposefully-designed farm wouldn’t have been a problem.

That’s why it’s crucial that container farms purposefully provide adequate airflow, temperature controls, dehumidification, CO2, etc. to their units.

That’s a challenge for most repurposed shipping container farms simply because of the extreme constraints the structure provides.

Repurposed shipping containers can have structural integrity issues

An often overlooked danger of repurposed containers is the limits of their structural lifespan.

Remember, these things have been around the world a few times and battered by corrosive salt water, high winds, and many a forklift operator.

That means they were worn out well before they were made into farms.

This limits the life of the farm significantly. In extreme cases, the quality of the container can be so low that we’ve known farmers whose farms were condemned by the city — an enormous and painful blow when you’ve spent tens of thousands to start a farm.

If you go this route, please be sure you carefully inspect the structural integrity of your container! This industry will not move forward if passionate, local farmers like yourself are investing in farms that fail to function in a year or two.

Light, heat, and layout must be balanced appropriately in any indoor farm

The relationship between light and heat is a largely antagonist one.

Because light and heat are “coupled”, supplying the quality (i.e. intensity of light) needed for plants to grow to their full potential also increases the amount of heat in the growing environment.

Simply put: when light goes up, heat goes up with it. The problem is that plants like light, but they don’t like heat.

As we saw in the previous section on the importance of environmental controls, this delicate balance between light and heat is amplified in dense environments.

Because of their tight spacing, container farms face an interesting conundrum when it comes to this messy triangle. They need high-intensity lighting to grow their crops but don’t often have the space required to install adequate HVAC units to deal with the heat created by these lights.

The result? Many container farms sacrifice productivity by being forced to use less than adequate LED lights to avoid adversely affecting their plants with heat and humidity.

Thankfully, there are some container farms out there mitigating this antagonistic relationship with intent-informed design.

By building a container that’s intentionally designed and equipped to grow plants, companies like Modular Farms in Canada and several Chinese and Japanese container farm companies can manage their growing environments effectively (among other things like moving around and inspecting plants easily).

When doing your due diligence on any future indoor farming equipment, be sure to carefully inspect how the system deals with the antagonistic relationship between light and heat. If you provide the plants the proper light intensity, you’re going to be producing heat and this heat can throw your system into a tailspin if not managed effectively. Make sure you have a way to deal with it!

Remember, if you want to produce high quality crops consistently, you need high quality light. You are replacing the sun after all.

Ignoring human workflows is never a good idea

Farm environments aren’t just designed for plants. They also need to be designed for people. The problem with shipping containers is that they’re not designed for people and that poses some real issues for farmers.

There are two reasons to keep your farm labor-friendly: the first is that labor is money, and the second is that there’s nothing worse than working in a cramped, confined space for dozens of hours each week. It can be enough to drive you insane, or at the very least make you dread coming to work.

Ergonomics — or how efficiently your workplace is set up for workers — is also important, yet this isn’t something you really think about when shopping around for a farm. Our advice? Don’t neglect it!

With those two goals in mind, container farmers must ask and answer important questions about how people will interact with the container farm.

Can I see all my crops easily?”

“Could I work in here happily for several hours each day?”

“Can more than one person work comfortably in this farm?”

These are all questions to answer before making such a large investment.

The most practical way to feel out the workflow in your future farm is to visit a variety of container farms before buying one and see how they feel.

Talk to other farmers who’ve been farming for a while and get their feedback. You won’t regret it!

OPEX and CAPEX should be appropriately balanced

When it comes to starting a business, ignoring your market research or failing to fully understand your financial projections is just rolling the dice.

If you want to stay in business, you have to know you can earn a profit. (That’s why it’s critical every aspiring farmer conducts a feasibility study to assess the financial potential of your farm!)

And a major part of this research phase is understanding the right balance of capital expense and operating expense. Unfortunately, this is also where many new farmers can fall prey to being a little too frugal.

With roots in farming ourselves, we know the temptation to do things on the cheap. There’s something so seductive about scrapping a farm together with inexpensive components. But we also know that skimping on your initial investment may actually come back to bite you when it comes to the cost of running the farm.

Just remember that most of the time when you pay less upfront (CAPEX), you end up having higher costs as you run the business (OPEX). Pay more upfront, and the investment will keep operating costs lower in the future. Again, this isn’t always the case, but 9 times out of 10 it holds true.

The same goes for container farms, or any indoor farming equipment for that matter.

Container farms can be less expensive to set up than many other farms like greenhouse or warehouse operations, but the constraints of the container can drastically increase the cost of running your farm. Especially when you have to add or replace equipment that fails, and your labor costs go up because of the increased time spent performing daily tasks like inspections and harvesting.

Don’t forget you’re starting a commercial farm here, not a backyard garden, and your goal is to grow and sell good food.

If you’re starting a system that hinders productivity (both for plants and workers) and requires upgrades or expensive maintenance to operate, you’re actually hurting your ability to accomplish your goals.

At the end of the day, cheap is not actually that cheap.

Beware vanity metrics

Farmers almost always make money by selling pounds (or ounces) of produce. Rarely do they sell a number of plants rather than a weight.

That’s why it’s so dangerous to measure a system’s economic potential with metrics like “plant sites.” You may be able to grow an incredible number of plants per square foot, but if they’re small and unsalable then it’s a metric that at best is useless, and at worst is intentionally misleading. An example of this could be a microgreen tray with “1000 plant sites in 1.5 square feet!”

This means that biomass is the only truthful and non-subjective metric.

Remember, vertical farming is not about how much production you can possibly cram into a space. It’s about growing better food closer to market and maximizing your production as a function of the resources you invest, such as capital, light, water, energy, and labor.

The best way to measure the productive and economic potential of your future farm is to compare the capital expense divided by the pounds of produce. That will not only give you an idea of how much your system will yield, but will also allow you to conduct appropriate market research based on weight, not plant sites.

Again, while it’s possible some chefs or farmers’ market customers may buy a head of lettuce, the majority of your markets will want to know your price per pound or your price per ounce.

Like the simplified example used in the video above, imagine that one farm offers 2,000 lb/year of greens and costs $90k in capital expenses (i.e the price you pay for the farm, delivery, installation, and any modifications needed for it to perform when you plug it all in).

Another offers 4,000 lb/year of greens but costs $135k. The second option might take a little longer to pay off, but will be more profitable in the long run. (This is overly simplified so please do a feasibility study to get specific numbers!)

Remember, vertical farming is not about how much production you can possibly cram into a space. It’s about growing better food closer to market and maximizing your production as a function of the resources you invest, such as capital, light, water, energy, and labor.

The bottom line: Container farms can play a significant role in the future of our food system.

The world is begging for better food.

People have lost faith in labels and they’re sick of low quality food they see at the grocery store. They’re demanding fresher food, but can only get it if they have local farmers near them to supply it.

Container farms can play a significant role in solving this supply problem by helping more local farmers get started growing food much closer to market.

But not all container farms are created equal.

Repurposed containers, while a prize of pop culture, require too much compromise to be truly productive modern farming machines in the long run.

We have much more faith in custom built containers that practice intent-informed design and take a ground-up approach to environmental controls, labor workflows, and much more. They’re just much more efficient and effective at helping farmers accomplish their goals.

So while container farms have the potential to fundamentally change the game when it comes to growing better food closer to the markets that want it, these farms must survive to be impactful.

Why did we write this?

Our goal with this piece, like most of the articles we write, is to move the industry forward. Everything we do here at Bright is about helping the local farmer succeed and it pains us to see the opposite happen.

We believe that by being honest about the benefits and challenges, more farmers will start sustainable businesses and help supply the increasing demand for better food.

Do you have experience growing in a container? Do you have questions for those who do?

Note: Repurposed shipping containers and containers designed specifically for growing crops are fundamentally different. In most cases, the latter have mitigated the majority of these issues in the design phase.

This Urban Farming Accelerator Wants To Let Thousands Of New Farms Bloom

08.23.17

This Urban Farming Accelerator Wants To Let Thousands Of New Farms Bloom

Kimbal Musk’s Square Roots is giving aspiring urban farmers their own shipping containers and helping them sprout a new business, in the hopes of creating a new agricultural system.

“We are successful if the farmers are successful. So we wake up every morning thinking: how can we help the farmers be more successful?” [Photo: courtesy Square Roots]

In a parking lot outside a former pharmaceutical factory in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant, 10 entrepreneurs have spent the last nine and a half months learning how to take on the industrial food system through urban farming. Square Roots–a vertical farming accelerator co-founded by Kimbal Musk, with a campus of climate-controlled farms in shipping containers–is getting ready to graduate its first class.

With a new round of $5 million in seed funding, led by the Collaborative Fund, the accelerator is making plans to build new, larger campuses in other cities.

“Is it going to be one company that takes down the industrial food system, or is it going to be thousands of companies working together on a better food system?” [Photo: courtesy Square Roots]

In the program, each entrepreneur is temporarily given a single upgraded shipping container, filled with vertical growing towers, irrigation systems, and red and blue LED lights in a spectrum tuned to help grow greens. Then they spend roughly a year learning the skills to grow food–no prior experience is necessary–developing business plans and working with coaches and experts to improve their entrepreneurial skills. By the end, in theory, they’ll be ready to launch an urban farming business of their own.

Musk, who runs several health-focused restaurants and nonprofit school gardens (and is Elon’s brother), saw the need for a large network of well-trained young entrepreneurs who could quickly grow urban farming. “We wanted to come up with a model that scaled small urban farming, so literally every consumer of food can have a direct relationship with a farmer,” says Square Roots co-founder and CEO Tobias Peggs.

“We wanted to come up with a model that scaled small urban farming, so literally every consumer of food can have a direct relationship with a farmer.” [Photo: courtesy Square Roots]

“Is it going to be one company that takes down the industrial food system, or is it going to be thousands of companies working together on a better food system? We definitely believe the latter,” he says. “So part of the engine that we’ve created here is that by training these young people…at the end of that program, they’re armed with the tools that they need to go out and set up their own food business. The hope is there will be tens of thousands of new businesses that end up being formed.” The program offers mentorship and can help connect entrepreneurs to investors.

In a learn-by-doing model, everyone immediately starts farming. “When this first cohort joined on November 7, on that day, literally the farms were dropped from a truck onto the parking lot,” Peggs says. “Eight weeks later, we had our first farmers market in Bed-Stuy, where those people had learned to grow really tasty food. The whole system is kind of geared up to have a very fast learning curve.”

I think it’s important to expose people to urban farmers.” [Photo: courtesy Square Roots]

As they grow and sell greens during the program, the entrepreneurs make money; the accelerator keeps a portion of the profits to fund itself. “Our incentives are aligned,” he says. “We are successful if the farmers are successful. So we wake up every morning thinking: how can we help the farmers be more successful?” Even with a single shipping container farm, Peggs says that it’s possible to run a profitable business.

One pair of entrepreneurs worked together to launch a farm-to-desk delivery program that brings fresh greens to dozens of New York City offices. Another student is focused on growing greens for low-income neighborhoods. Someone else launched a business delivering produce to New Jersey while running her Square Roots farm. A former engineer is developing an improved lighting system for indoor farming and plans to launch an equipment business. Another entrepreneur used data analysis to perfect a growing recipe for heirloom basil, which he sells to restaurants and markets. (The accelerator’s layout, with modular growing containers, also allows it to study data about yield and quality and improve the technology for future students).

“What I found most valuable is you’re pretty much thrown into operating a business, and you learn as you go.”[Photo: courtesy Square Roots]

“The way that I learn is through experience and also through imitation,” says Nabeela Lakhani, one of the first class of entrepreneurs, who joined the accelerator after graduating from a public health and nutrition program. She had no prior farming experience. “What I found most valuable is you’re pretty much thrown into operating a business, and you learn as you go, which was perfect for me.”

Lakhani partnered with a SoHo restaurant, Chalk Point Kitchen, to become its “official farmer,” growing food on demand for the chef. The restaurant buys her entire yield from the shipping container, and Lakhani provides a year-round supply of produce. She also visits the restaurant once a week to wander around tables talking with customers.

[Photo: courtesy Square Roots]

“I think it’s important to expose people to urban farmers,” she says. “You should be friends with your farmer–that’s how local food should be. Just the way the chef comes out and says hi, I think it should be the norm that the farmer comes out and says hi. That builds trust between the consumer and the food system.”

The first cohort will graduate in October, and the accelerator is taking applications for its next class; in 2016, it had 500 applicants for 10 spots. In its new location in a yet-to-be announced city, it plans to have larger campuses with room for more students. The founders also hope to quickly launch in more locations. “It’s all stemming from the mission of real food for everyone,” says Peggs. “Ultimately, we want to put a Square Roots campus in every city in the U.S.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Adele Peters is a staff writer at Fast Company who focuses on solutions to some of the world's largest problems, from climate change to homelessness. Previously, she worked with GOOD, BioLite, and the Sustainable Products and Solutions program at UC Berkeley.

How Local Roots Is Helping Solve The World's Food Waste Problem With Robots and Tech

How Local Roots Is Helping Solve The World's Food Waste Problem With Robots and Tech

August 22, 2017

By 2050, the world needs to feed an expected 9 billion mouths, but agricultural inefficiencies, food waste and climate change are limiting our capacity the feed the world of tomorrow. One Los Angeles company is trying to make inroads in this complex problem.

Ellestad is the CEO of Local Roots, a vertical farming company that uses technology to grow the equivalent of five acres of food in a 40-foot shipping container. They’re part of a growing wave of indoor farmers, who are using hydroponic technologies to raise food on a massive scale, at a fraction of the land required by conventional means.

Local Roots Butterhead lettuce growing inside of our TerraFarms™ | Courtesy of Local Roots

Los Angeles may seem like an uncanny place to start an indoor farming business, with its Mediterranean climate and year-round growing season. The city of Angels is surrounded by some of the most profitable agricultural lands in the continent. Over a third of the country's vegetables and two-thirds of the country's fruits and nuts are grown in the state.

“We’re sandwiched between Salinas, the Imperial Valley, and Mexico,” Eric Ellestad says, referring to places of rich agricultural productivity. “It doesn’t get any more competitive than this.” But, he is out to prove a point.

“The reason we chose Los Angeles is because it’s really the market that you need to prove that you can compete and that you can scale anywhere,” he says.

Based in Vernon just five miles south of downtown Los Angeles, Local Roots can grow 20 to 70 thousand pounds of food in just one shipping container. The operation can be powered entirely by solar energy and uses 99 percent less water than conventional farming techniques. All of the technology, from growing algorithms down to the PVC pipes are developed in-house, which makes them unique from their competitors. This move saves them money and makes their operation easily customizable to client needs.

Eric Ellestad with on of his TerraFarms | Clarissa Wei

“We realized that we were going to get trapped in a high price market if we just bought the available parts,” Ellestad says. “So we developed all our own technology and standardized those designs.”

Local Roots specializes in, though is not limited to, leafy greens like butter lettuce, arugula and all different sorts of kale. Every variety is programmed to its own algorithm and the efficiency of that makes it so that they can harvest every 12 days (versus 36 for conventional farming methods). The entire operation is confined to a warehouse in the industrial neighborhood of Vernon and has all the hallmarks of a tech start-up.

Ellestad himself comes from a venture capitalist background and secured one million dollars in funding for the company from venture capitalists, which was launched in 2013. Today they’re a team of 30 people, mostly young scientists and coders, who work in an adjacent air-conditioned office to the warehouse. The farmers, who harvest and propagate the plants, are dressed appropriately mostly in jeans and a T-shirt.

“We’re synthesizing conventional growing practices with technology. This means higher wages for our staff and that we can move more plants in the system,” he says.

Our proprietary red and blue LED lights that help the Butterhead lettuce grow at maximum efficiency | Courtesy of Local Roots

Currently, they have three shipping containers that can hold up to 16,000 plants. Nearly four years in, their client roster includes Space X, Mendocino Farms and Tender Greens. But this is simply a start. The grand ambition is to achieve an international reach.

“Our mission is to improve global health by building a better food system,” Ellestad says. “Simply being a produce company in Los Angeles doesn’t meet that goal.”

Farms emit about 13 percent of the world’s greenhouse gases, he notes. That and a growing world population — a projected 9.7 billion people by 2050 — are his primary motivations.

“We’ll need to grow 70 percent more food by 2050,” he says.

By automating the growing process, Local Roots is able to harvest in a third of time that it takes for a conventional farm to grow food. And of course, the greens are grown sans pesticides because everything is contained in a controlled environment.

Our proprietary red and blue LED lights that help the Butterhead lettuce grow at maximum efficiency | Courtesy of Local Roots

“We develop a model for each crop, determine the set of conditions, and get the most efficient production while still optimizing what the customer wants,” he says.

The technology does have its drawbacks, however. Vertical farming technology is mostly targeted toward leafy greens. Fruit and nut trees are not ideal in shipping containers, and major carbohydrates crops like rice and wheat cannot be supported in such an environment. Because the operation is held in a closed-loop system, vertical farming, unlike other alternative forms of agriculture like no-till farming, does not contribute to soil health and biodiversity.

Still, it’s a step forward in alleviating the pressures of feeding a growing population.

Growlink Announces Strategic Partnership With Modular Farms

Growlink Announces Strategic Partnership With Modular Farms

Growlink Grow Controllers to be used in Modular Farms Container Farms

DENVER, CO (PRWEB) AUGUST 16, 2017

Modular Farms

We wanted a strong technology partner that would meet our needs for a reliable, easy-to-use farm, and Growlink provides that.

Growlink, a Denver-based technology company, announced today that it has formed a strategic partnership with Brampton, Ontario-based Modular Farms, to integrate its cloud-based grow controllers into their modular farm systems.

“We’re excited for this partnership with Modular Farms,” said Ted Tanner, CEO of Growlink. “Modular Farms has the potential to lengthen growing seasons, reduce local food insecurity, and stabilize a farmer’s income stream. We share their goals of bringing smart, fresh, local food to communities worldwide.”

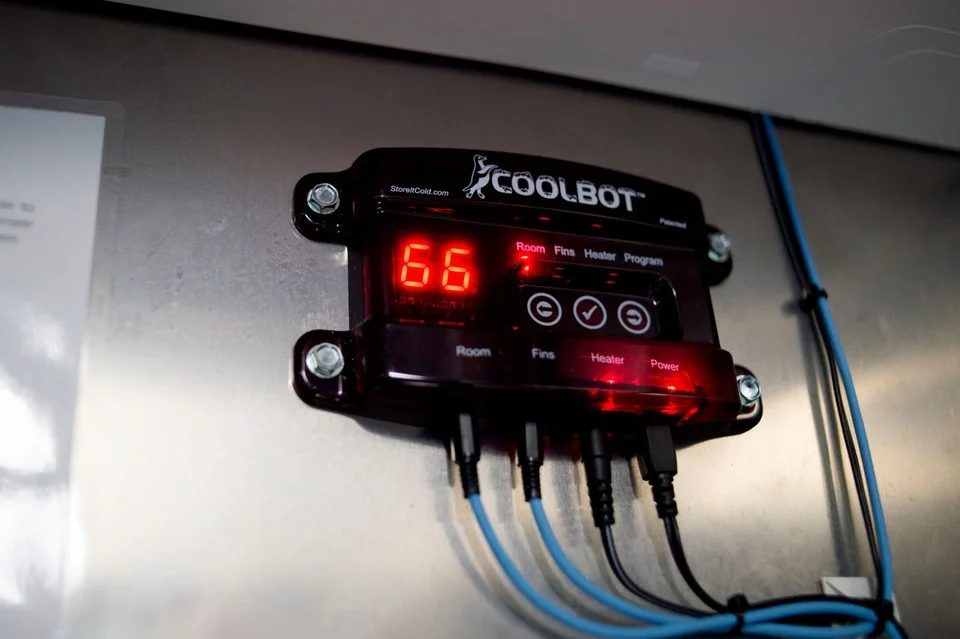

Modular Farms began selling its farm systems in November 2016. Instead of repurposing shipping containers, Modular Farm Systems are built from the ground up from composite, rust-resistant panels and are larger than traditional shipping containers at 40’ x 10’ x 10’. The larger size allows for better spacing between plans and lights and greater airflow. Every unit comes with two intensive days of training and 24/7 support.