Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

“The Future of Agriculture”: Goochland Tech Students Get New Vertical Farms While Demand Grows At Area Food Banks

"Meredith Thomas said this kind of farming is more environmentally sustainable — it uses no soil, no pesticides and roughly 90 percent less water. She added this kind of farming is more environmentally sustainable — it uses no soil, no pesticides and roughly 90 percent less water. The nutrients and PH are controlled by sensors that check the water every single morning, and add nutrients, or PH balancing solution, or even water,” Thomas said."

GOOCHLAND COUNTY, Va. (WRIC) — Farm to table has a whole new meaning.

“It’s literally grown, sometimes even harvested and consumed in the same room,” said Meredith Thomas with Babylon Micro-Farms.

Vertical Farming is one of the fastest growing trends in food production. Some call it the future of agriculture. Now, students at Goochland Tech will get the chance to learn all about it while their local community reaps the benefits.

In a new partnership between GoochlandCares and Goochland Tech, two new vertical farms have been installed at the high school. According to Babylon Micro-farms, the Charlottesville company who made the farms and installed them in early August, “a single micro-farm takes up only 15 square feet but has the productive capacity around 2,000 square feet.”

The farms are active year-round and all aspects of farming are controlled by a cell phone app.

“It’s a hydroponic farm designed to take the green thumb out of growing,” Thomas said.

She added this kind of farming is more environmentally sustainable — it uses no soil, no pesticides and roughly 90 percent less water.

“The nutrients and PH are controlled by sensors that check the water every single morning, and add nutrients, or PH balancing solution, or even water,” Thomas said.

Students will be taught about vertical farming while also supplying food to the pantry at GoochlandCares, which distributes food to neighbors in need.

“The pantry will receive both nutritious, locally grown fresh produce year-round and dishes prepared by the students with the harvests from the farms,” said Janet Matthews with Babylon Micro-Farms.

8News has witnessed long lines outside of food banks in our area for months. In Chesterfield on Friday, cars filled two lanes for over half a mile leading up to the Chesterfield Food Bank. That kind of backup has been seen on Ironbridge Road every weekend for the past several months.

Before COVID-19 spread around the world, the Chesterfield Food Bank was helping anywhere from 8,000 to 12,000 people a month. Now, they say nearly 30,000 people utilize the food bank’s distribution programs each month — with 200 to 400 volunteers offering their help every week.

Chesterfield Food Bank averaging a million meals per month during the pandemic, triples in donations

“The recent COVID-19 pandemic has shown us the weak links in our country’s food distribution system, affecting everyone especially those who are most vulnerable. We hope that this partnership will be a model for many other food pantries to have a reliable in-house resource to provide fresh food,” said Sally Graham, Executive Director of Goochland Cares.

On Wednesday, the food pantry’s manager, Terri Ebright, said her team is “ecstatic” about the food that will be coming in. She said the demand for food has also grown at her pantry during the pandemic. “Our clients are relying on us even more.”

Goochland Tech Culinary Arts instructor David Booth said the new farms are a big deal for students.

“Right now I’ve got five different lettuces in there that I know half my students have never seen or tasted before,” he said. “It’s one of those things you don’t even really have to design a lesson plan around,”

“I just see it as a boundless opportunity. I really do,” Booth said.

You can learn more about how vertical farming works here.

By Alex Thorson

Posted: Sep 16, 2020 / 09:01 PM EDT - Updated: Sep 16, 2020 / 09:19 PM EDT

US Farming Is Tasteless, Toxic And Cruel

and its monstrous practices have no place here: Radio 4’s veteran food presenter Sheila Dillon decries ministers’ dangerous plans

By SHEILA DILLON FOR THE DAILY MAIL

19 September 2020

And its monstrous practices have no place here: Radio 4’s veteran food presenter Sheila Dillon decries ministers’ dangerous plans

British farming and food production are a remarkable success story. In recent years, this sector has been at the forefront of a revolution that’s transformed the quality of our food — and acted as a guardian of our countryside.

Through the vision and dedication of our farmers, Britain is increasingly a global leader in animal welfare, environmental protection, and high standards of produce. Now all these achievements are at mortal risk. As we prepare to leave the European Union at the end of this year, our impressive agricultural system could soon be wrecked by ruthless competition and a flood of cheap imports.

The most serious threat comes from the U.S., whose vast and unwieldy farming industry is far less regulated than ours.

In the name of efficiency, it has built a highly mechanised, intensive, and shockingly cruel approach which keeps animals in conditions so appalling it’s hard for us in the UK to grasp. Meanwhile, an arsenal of chemicals that are banned here are also deployed on these poor creatures.

It is not the sort of produce that should be allowed to swamp our own. When Brexit supporters spoke of ‘taking back control’, they did not envisage the destruction of British farming caused by mass-produced goods soaked in chlorine and cruelty.

In an attempt to prevent this grim eventuality, a last-ditch battle is under way at Westminster aiming to establish essential safeguards in post-Brexit Britain.

As the Agriculture Bill — which sets out a new domestic, post-Brexit alternative to the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy — makes its way through Parliament, MPs in the Commons and peers in the Lords have tried to impose amendments to keep Britain’s high standards of animal husbandry and environmental care. So far the Government has rejected all such proposals. Desperate to reach a trade deal, ministers seem unwilling to block the hugely influential U.S. food and agriculture lobby from gaining access to our market.

Their argument is that, in the brave new world of deregulation, consumers will enjoy more choice and, crucially, will have access to ‘cheap’ food. But cheapness will come at a huge cost to our health, our countryside, our rural economy, and our animals.

The reality is that choice will be restricted — because British farmers and producers will find it impossible to compete. From the supermarkets to takeaways, this ugly juggernaut of American food will sweep all before it.

The Agriculture Bill is about to go to the final stage of its passage through Parliament. There is one last chance for legislators to stop a free-for-all from which our agriculture would emerge the loser.

As someone who has covered the food industry for 20 years presenting The Food Programme on BBC Radio 4, I am deeply alarmed at the prospect of the advances British food has made in recent decades going into reverse.

Before COVID, British food was flourishing as never before. I think of the surge in high-quality bakeries, of our farmhouse cheeses beating rivals across the world — we produce more than France.

Even McDonald’s UK now uses free-range eggs and organic milk and recently won an RSPCA award for its animal welfare standards. I need hardly say it’s not how McDonald’s operates in the U.S.

It’s all part of Britain’s deep and enduring compassion for animals. We have 25 million free-range hens here, more than any other country — and more free-range pigs than anywhere in Europe.

In frequent talks with farmers, I have been struck by how they see themselves, not just as producers, but as custodians of the land, a vital role they fill with imaginativeness in an age of mounting concern about climate change.

The U.S. farming model is completely different. Its aim is not to work with nature but to dominate it. Industrialised and chemicalised, the entire system is a monument to the denial of biology.

I am not in any way anti-American — I’ve lived across that wonderful country in Indiana, California, Massachusetts, and New York. I’m married to an American: my son and his family live in Pennsylvania.

It’s precisely because I visit regularly, and have seen at first hand the harshness of U.S. food production, that I feel so strongly.

The ‘chlorinated chicken’ has rightly become a symbol of U.S. farming at its worst, but few ask why poultry has to be washed in chlorine before it can be sold. It is because the birds are kept in such over-crowded squalor and so pumped with chemicals during their brief, unfortunate lives.

The same applies throughout American industry. Even the British Government’s farming Secretary George Eustice has admitted U.S. animal welfare law is ‘woefully deficient’. Pigs are reared in grotesquely inhumane battery farms. More than 60 million are treated with the antibiotic Carbadox, which promotes growth and is rightly banned in the UK.

Similarly, U.S. cattle are fed steroid hormones to speed growth by 20 percent — the use of such chemicals has been illegal in Britain and the EU since 1989. And as the cattle are kept in vast confined feeding pens, they need regular antibiotics.

Incredibly, some staff processing carcasses at huge meatpacking plants wear nappies because they are not allowed time off to go to the lavatory. In arable production, pesticides are used on a scale far beyond anything in Britain. In recent decades, the U.S. has banned or controlled just 11 chemicals in food, cosmetics, and cleaning products — the EU has banned 1,300.

Polar opposites: Cows in a British field, and in beef pens in Texas

In U.S. farming there’s almost no effort to mitigate climate change yet here the National Farmers’ Union is committed to achieving zero carbon production by 2040. What will happen to that commitment if cheap U.S. food floods in?

The U.S. genetically modified crops to be resistant to Roundup weedkiller — but after weeds grew resistant to Roundup and flourished, one U.S. farmer told me proudly crops were now engineered to be resistant to the infamous Agent Orange, a defoliant used by the U.S. military to kill vegetation in the Vietnam War.

Environmental devastation and health problems — including disabilities to as many as a million people — were caused in Vietnam by Agent Orange. Is this a road we want to go down in Britain?

The so-called cheapness of American produce is a delusion. These farming methods carry a heavy price in quality and health. A battery chicken is tasteless compared to an organic one, just as factory-farmed salmon has nothing of the flavour of wild.

Cheap, low-quality foods have brought with them disturbing health problems including obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

The coronavirus crisis proved the need for resilient supply lines. But that cannot be achieved if we ruin our own domestic agricultural system and become reliant on imported food.

In World War II, when the survival of the nation was imperilled, the Government attached huge importance to domestic food output, reflected in the propaganda campaign ‘Dig for Victory’ and the Women’s Land Army. We need that collective spirit today.

It would be stupidity beyond measure to obliterate our farming industry for a short-term, unbalanced trade deal with the U.S.

A trade deal without agricultural safeguards would be a calamity for British farming and our prosperity. One in eight jobs in Britain is in food supply, while food exports brought in £9.6 billion to the economy. All that will be lost if cut-throat competition prevails.

And a vital part of our heritage will also be lost. From the robust imagery of John Bull as a yeoman squire to William Blake’s Jerusalem, with its evocation of our ‘green and pleasant land’, the countryside has always held a central place in our national soul. It must not be sacrificed on the altar of illusory cheapness or trans-Atlantic subservience.

Lead photo: It’s all part of Britain’s deep and enduring compassion for animals. We have 25 million free-range hens here, more than any other country — and more free-range pigs than anywhere in Europe

Sheila Dillon presents BBC Radio 4’s The Food Programme.

Energy Use In Food Production

The U.S. food system uses a massive amount of energy from start to finish. In 2018, the U.S. consumed 101.1 quadrillion Btu (British thermal units) of energy. The food system makes up 10 percent of that total, landing it at about 10.11 quadrillion Btu

By The Choose Energy Team

November 26th, 2019

We use a whole lot of energy to produce our food

The U.S. food system uses a massive amount of energy from start to finish. In 2018, the U.S. consumed 101.1 quadrillion Btu (British thermal units) of energy. The food system makes up 10 percent of that total, landing it at about 10.11 quadrillion Btu.

That number might not mean much at first glance, but put another way, the U.S. consumes as much energy preparing and transporting food as France uses to power the entire country for a year.

Where does that energy come from?

Food systems around the world account for about 30 percent of the world’s total energy consumption. Since most food systems are run primarily on fossil fuels, that means they also account for 20 percent of our global greenhouse gas emissions.

These emissions take place at every step of the food chain. Manure and fertilizer give off nitrous oxide while cattle and other animals produce methane. Machinery requires diesel and gasoline, and the entire process is fueled by coal and natural gas power plants, creating carbon dioxide.

How is that energy used?

The energy in food production can be broken down into four parts: agriculture, transportation, processing, and handling.

Agriculture

Agriculture uses about 21 percent of the total U.S. food production energy. This accounts for everything involved in the growth and cultivation of food crops. 60 percent of this energy is consumed directly in the use of gasoline, diesel, electricity, and natural gas, while the rest is indirect through fertilizer and pesticide production. In total, agriculture consumes roughly 2.1 quadrillion Btu of energy each year, enough to power the entire country of Norway.

Transportation

The transportation of food from farm to table accounts for just under 14 percent of the energy that goes into producing food. Romania could power itself for a year on the 1.4 quadrillion Btu it takes to ship avocadoes from South America (among other tasty imports).

Food Processing

Food processing refers to the transformation of raw ingredients into a food product, in other words, turning raw corn into cereal and the like. This section of the system makes up about 16 percent of the total. This breaks down to about 1.6 quadrillion Btu per year, equivalent to the total energy use of Nigeria.

Food Handling

Food handling is by far the largest sector of energy in producing food, and accounts for nearly half of the energy used in food production – over 49 percent. This piece of the system includes retail, restaurants, packaging, and consumers. The energy used to package milk and keep it refrigerated in the grocery store and at home falls into this category. At 5 quadrillion Btu, the food handling sector’s total energy is more than enough to power a year of life in Taiwan.

Energy-efficient foods

Certain foods require less energy to produce than others, whether because it requires less land and water or because there are fewer industrial processes needed to produce it. The most energy-efficient foods include wheat, beans, fish, eggs, nuts, and other non-resource-intensive products.

The least energy-efficient foods are animal-based products, particularly beef, lamb, and goat. This is because beef requires up to 20 times more resources and emits 20 times more greenhouse gas emission than plant-based protein sources. Poultry and pork use slightly less energy but are still far bigger emitters than plant products.

This doesn’t mean you have to be a vegetarian to cut down energy use. Just reducing the amount of meat and dairy you eat can allow you to have a much lower impact diet. Regardless, both meat-based and vegetarian diets rely heavily on fossil fuels, so neither is sustainable long-term in the current food system.

How to reduce food system energy use

Because so much of the energy used in food production comes from non-renewable resources, it’s important to make the food system more energy efficient. A few key ways to start making a difference at home are:

Buy only as much food as you eat. One of the easiest ways to help conserve energy in food production is to waste less. It’s estimated that 40 percent of food in the U.S. goes uneaten. In 2017, that added up to 38 million tons of food waste. As a comparison, that’s the weight of 38 million polar bears, 5.5 million elephants, or nearly 300,000 blue whales.

Buy food that is locally sourced. Shop at local farmers’ markets instead of buying produce at the grocery store. You’ll be supporting local farmers and saving the energy needed to transport perishable foods from across the world.

Invest in energy-efficient food storage. Get an EnergyStar refrigerator, which use 20%-30% less energy. Also, keep your refrigerator fully stocked. If you don’t have enough food, keep containers of water in there instead. It may sound counterintuitive, but your refrigerator works most efficiently when it’s full.

Is Vertical Farming The Post-COVID Future of Food Production?

New Canadian agtech company Local Leaf Farms opens first vertical farming facility, producing fresh, safe andsustainable hyper-local produce. Barrie location is the first of 20 planned to open by the end of 2025

NEWS PROVIDED BY: Local Leaf Farms

Jun 22, 2020

New Canadian agtech company Local Leaf Farms opens first vertical farming facility, producing fresh, safe, and sustainable hyper-local produce. Barrie location is the first of 20 planned to open by the end of 2025.

BARRIE, ON, June 22, 2020,/CNW/ - New Canadian agtech company Local Leaf Farms officially opened its first vertical farming facility today, establishing itself as a company ready to transform Canada's food industry. Using vertical farming technology, Local Leaf produces hyper-local produce that's fresher, more sustainable, and fully traceable - directly addressing many of the challenges of food production highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Alongside the launch, Local Leaf also released the findings of a study conducted by IPSOS that confirmed the ways in which COVID-19 has impacted the way Canadians are making decisions about food: according to the survey, 68% of Canadians say the pandemic has made food safety more important to them and 47% say locally produced food is today their top purchase driver.

"Canadian consumers are demanding greater transparency about the food they eat. And that demand has never been more urgent," said Steve Jones, President, and CEO of Local Leaf Farms. "As we begin to consider a post-COVID reality, we need to have real discussions about the stability - and overall future - of food production in this country. Local Leaf is bringing leading-edge technology to the food sector to produce the fresh, safe, and sustainable produce that Canadians are asking for."

Today, the average package of leafy greens in Canadian grocery stores travels 3,000 km before it lands in a shopper's cart. This journey can take up to two weeks and can cause produce to lose up to 70% of its nutritional value - not to mention the impact on its taste, texture, and flavour. Local Leaf Farms' technology allows the company to reimagine the journey food takes from the farm to the store. All Local Leaf Farms produce can be at local grocery stores just hours after it was harvested, not only because of proximity but because, unlike any other produce sold in Canada, it can be 'drop shipped': delivered directly, without the need to pass through distribution centres, maximizing freshness and shelf life.

Local Leaf also offers a fully traceable food source, with instant access to information about the food from seed to shelf. The company's proprietary technology and mobile app allow retailers and consumers to know exactly where their produce comes from, including detailed information on how it was grown, when and by whom. The farm, which includes an 20,000 square foot community garden, is even open to the public once a month, allowing people to see and connect with their food.

Of particular importance in our current reality, vertical farms like Local Leaf eliminate the need to rely on migrant labour - a workforce that has faced a severe threat in the face of COVID-19.

A growing number of Canadian investors and stakeholders are recognizing the need for Canada to rebuild its capacity to produce goods through stronger innovation - and are looking to the vertical farming industry as a viable solution. Federal Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry, Navdeep Bains, is a vocal supporter of Local Leaf Farms' mission.

"It is vitally important that all Canadians have access to healthy, sustainable food," said Minister Bains. "Local Leaf Farms is taking an innovative approach to this challenge by using the latest in agricultural and digital supply chain technologies, and data-driven decision making, to produce a reliable domestic supply of nutritious food, with a smaller environmental footprint."

The IPSOS research also identified the following key insights about changing consumer perceptions:

Nearly all Canadians (96%) prefer to buy produce grown in Canada, whether in their local community (21%), their province (41%), or elsewhere in the country (34%).

There is a widespread belief (68%) that eliminating plastic from food packaging is important, and a stated preference (51%) for non-plastic, compostable, plant-based material. By contrast, just 21% would prefer produce to come packaged in recycled plastic, sometimes referred to as recycled PET.

Food safety matters: 88% of Canadians consider food safety important to their purchase decision when buying leafy greens and produce.

The top food safety concerts are hygiene-based: almost 1 in 2 Canadians are concerned about product handling safety standards and 1 in 4 called out the cleanliness of the growing environment.

Local Leaf's Barrie location services grocery stores, food service providers, and home meal kit providers within 50km of the farm. All of the produce, which is sold under the My Local Leaf brand, is pesticide- and herbicide-free, non-GMO and packaged in 100% plastic-free compostable packaging. The company is on track to open its next location in Kingston in the coming months - and has a scale goal to launch 20 locations across the country by the end of 2025.

For more information about Local Leaf Farms, visit localleaffarms.com.

SOURCE Local Leaf Farms

For further information: Julie Pieterse, Craft Public Relations, 647-282-6118 | julie@craftpublicrelations.com

CSO Pleased With Schedule For Lawsuit Asking To Restrict Supplies of Organic Foods

Lee Frankel, executive director of the CSO, stated, “The sooner growers can be sure that the rules established by Congress, the US Department of Agriculture and the National Organic Standards Board that allow for growers to use containers in their operations will remain in place, the more quickly growers can get back to focusing on providing nutritious and delicious organic fresh produce to consumers looking for ways to strengthen their immune systems during the COVID-19 outbreak.”

SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA June 12, 2020 – The Coalition for Sustainable Organics (CSO) is pleased with the schedule set by Judge Seeborg in the lawsuit seeking to strip growers of their rights to incorporate appropriate and legitimate growing techniques in their organic operations. The CSO continues to oppose the efforts of the Center for Food Safety and a handful of growers to limit the availability of fresh organic berries, tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers, leafy greens, herbs, microgreens, and mushrooms.

Lee Frankel, executive director of the CSO, stated, “The sooner growers can be sure that the rules established by Congress, the US Department of Agriculture and the National Organic Standards Board that allow for growers to use containers in their operations will remain in place, the more quickly growers can get back to focusing on providing nutritious and delicious organic fresh produce to consumers looking for ways to strengthen their immune systems during the COVID-19 outbreak.”

Under the Scheduling Order, USDA has until July 15 to provide the Administrative Record supporting its decision to deny the petition of the CFS to revoke certification of organic growers incorporating containers on their farms. A series of briefs will be filed culminating in a hearing currently scheduled for January 21, 2021, to present what will likely be the final arguments in the case prior to the judge’s decision.

The Department of Justice on behalf of the USDA stated in the case management order filed prior to the judge’s order that “The agency properly concluded that the OFPA [Organic Foods Production Act] does not prohibit hydroponic production systems. It properly determined that organic hydroponic systems cycle and conserve resources in a manner consistent with the vision for organic agriculture expressed by the OFPA, that hydroponic organic systems produce food in a way that can minimize damage to soil and water, and that hydroponic organic systems can support diverse biological communities. USDA fully explained these reasons and others in its decision denying the petition—a decision that courts review under an extremely limited and highly deferential standard.”

Frankel continued, “The CSO agrees with the USDA. We look to broaden the coalition to other producers, marketers, and retailers that support bringing healthy food to more consumers because we believe that everyone deserves organics.”

Modular Micro Farms: A New Approach To Urban Food Production?

One key tenet of the “urban resilience” idea is local food production. If fruits, veggies, and herbs are grown in cities, they’ll reduce the runoff, emissions, perishability and transport costs of produce

November 25, 2019

Nov 25, 2019,

Scott Beyer Contributor

A micro-farm installation creates farm-to-salad-bar food. BABYLON MICROFARMS

One key tenet of the “urban resilience” idea is local food production. If fruits, veggies, and herbs are grown in cities, they’ll reduce the runoff, emissions, perishability and transport costs of produce. They’ll also make cities more self-sustaining, rather than having to fully rely on food grown elsewhere.

The problem is that urban agriculture doesn’t always seem like a practical concept. Urban land is expensive, and the prospect of making it farmland - even in distressed cities - could present long-term opportunity costs if these cities later revive. Furthermore, the vertical farming idea - where structures are built to grow produce at large scales - seems premature, since this brick-and-mortar infrastructure must compete with cheap, horizontal farmland. As fellow Forbes contributor Erik Kobayashi-Solomon writes, vertical farming is still a largely untested concept that receives limited capital compared to standard farming.

An urban agriculture technique that seems more practical, though, is micro-farming, which involves fitting small farms into tight spaces, sometimes ad hoc. The website Lexicon of Food defines micro-farming as “small-scale farming that takes place in urban or suburban areas, usually on less than 5 acres of land.”

Modular micro-farming is a subset within this niche, using small, automated modular food-growing equipment, often contained within a few square feet. Modular farms are easier to use and possibly more scalable, since they can fit into almost any home or apartment.

One example of this modular approach is Babylon Micro-Farms, a startup based in my hometown of Charlottesville, VA. The company sells 32” x 66” x 96” tall machines that use controlled environment hydroponics to grow leafy greens, herbs, and edible flowers. The farms don’t have soil, sunlight or standard seeds. Instead, Babylon places seed pods onto its trays. Depending on the seed variety (Babylon has 227 of them), the machines use remotely-managed equipment to cast the appropriate water and light. This causes produce to generate significantly more per-acre yield than standard farms. Babylon’s 15sqft micro-farms are capable of producing as much produce as 2000 sqft of outdoor farmland.

Babylon's latest modular micro-farm model. BABYLON MICROFARMS

These modular farms can be connected together to create indoor farms of different scales that can work within existing buildings. Their operations are remotely managed via the cloud with real-time data collection on all aspects of the growing environment. This is an exciting development in a space that has remained out of reach for businesses and consumers due to high capital costs and complex technology with a steep learning curve.

Babylon sells these machines the way some green energy companies sell solar panels. Customers agree to a minimum 2-year lease, paying a fixed monthly fee. Babylon installs the machines, provides a subscription of growing supplies, and remotely manages the crop growth via the cloud using a proprietary software platform. This lets customers enjoy the produce without needing a “green thumb or any real expertise,” says Alexander Olesen.

Olesen co-founded the company with Graham Smith, when they were at the University of Virginia and participating in the iLab Accelerator at Darden School of Business. They incorporated in 2017, and now work in a small warehouse-style space near downtown Charlottesville. Babylon has 14 employees and $3 million in seed funding, including a grant from the National Science Foundation, and venture capital from Virginia, Washington, DC and Silicon Valley. They have dedicated these first couple years to building and testing the product, landing a few early clients for feedback. These include UVA, Dominion Energy, and some local restaurants, schools and country clubs.

But their ambitions go well beyond central Virginia. Olesen said the first major act of scaling is currently underway, with Babylon installing their farms in major corporate restaurants, cafeterias, resort hotels, and grocery stores. Because such institutions thrive on b-to-c relations, they would benefit from the experiential component of a modular farm. Rather than just saying they use organic food, they can show customers where and how it’s being grown.

“This has the additional value of being able to show your customers that you care about those things,” said Smith. “If it’s growing 10 feet from the table, that’s pretty clear.”

Babylon believes that their technology can increase the biodiversity of produce available to consumers in urban areas, so they place a lot of emphasis on the underlying plant science required to grow crops using their machines.

“One of the most exciting things about hydroponics is the amount of blue ocean space, it’s theoretically possible to grow any plant this way, yet only a handful of crops have successfully been commercialized,” said Olesen.

Babylon has a controlled environment test facility in Charlottesville where plant scientists run trials on seed varieties from around the world, dialing in tailored growth recipes to produce higher yields and consistent flavors. Their technology consists of an array of sensors and utilizes camera vision to create an automated feedback loop that analyzes the data to increase the rate at which growth recipes can be developed. In doing so, they plan to learn how to grow heirloom crop varieties and reintroduce them to the supply chain, leading to more options for chefs and consumers alike.

In the long run, Babylon plans to use their modular vertical farming platform to build larger farms capable of growing the majority of fresh produce for their clients. They envision micro-farming becoming an amenity in urban areas located in, or adjacent to, all grocery stores, foodservice operations, and food distribution hubs. These companies now get their supply from different farms nationwide, then process, package and sell it to consumers. The benefit to them of growing it onsite would be to significantly reduce perishability, which now wipes out 50% of food, much of it during the transport process, which can be over 1500 miles from farm to fork in the U.S. Not to mention the emissions generated by such a long supply chain.

Users scan crops into the farm, and Babylon remotely manages the growth cycle for them through... [+]

“Initially, we’re focused strictly on the b-to-b market, and utilizing these farms to grow food for companies with a known means of consumption or distribution,” said Olesen, while walking me through the facilities. “The next step…is creating these farms as a means for people to sell.”

This latter vision makes modular micro-farming seem like a viable future urban food source. Land owners in dense cities struggle to find the right surface lots to convert into vertical or horizontal farms. But Babylon’s 15sqft machine provides an adaptable solution that can work with existing infrastructure by slotting into unused space throughout urban areas.

Other companies have, for this reason, embraced small modular micro-farming. Ones like Cityblooms and Zipgrow focus on slightly larger, more commercialized modular units. However, small scale urban farms have faced a scalability issue; the technology that is commercially available only allows for basic automation, but lacks any feedback that would enable these farms to learn how to operate more efficiently. The most direct competitor to Babylon is InFarm, a Berlin-based startup that operates in Europe. They have created a system similar to Babylon’s, which has gathered momentum with installations in grocery stores across Europe. It’s an exciting prospect to think of indoor farms in grocery stores here in the U.S.

If any or all of these companies can make modular micro-farms a standard provider of fresh produce, it has the potential to disrupt the current supply chain - from manufacturers down to individual households. It would be an environmentally-friendly way to increase crop yields, reduce emissions, and feed people in the future. If it becomes a city phenomenon, in particular, it could be key to improving urban resilience across the U.S.

I am the owner of a media company called The Market Urbanism Report. It is meant to advance free-market policy ideas in cities. The Report features multiple articles daily, along with a video series that explains urban issues from street level. I’m also a roving urban affairs journalist who writes columns for Forbes, Governing Magazine and HousingOnline.com. For three years, I'm circling America to live for a month each in 30 cities, starting from Miami and ending in New York City. The point is to write a book about revitalizing cities through this Market Urbanism concept. But my articles cover other city subjects too. I have also written for the Wall Street Journal, Atlantic, American Interest and National Review. You can find my work at MarketUrbanismReport.com.

Building a Circular Economy in Charlotte

May 22, 2019

By Amy Aussieker

As the circular economy grows in Charlotte, our dependence on foreign imports would decrease and one area to benefit is local food production.

From growing locally both traditionally and through aquaponics/hydroponics to the reuse of organic waste – this opportunity has the possibility of transforming the food culture in Charlotte to a more sustainable, healthy, and accessible system.

Read Article

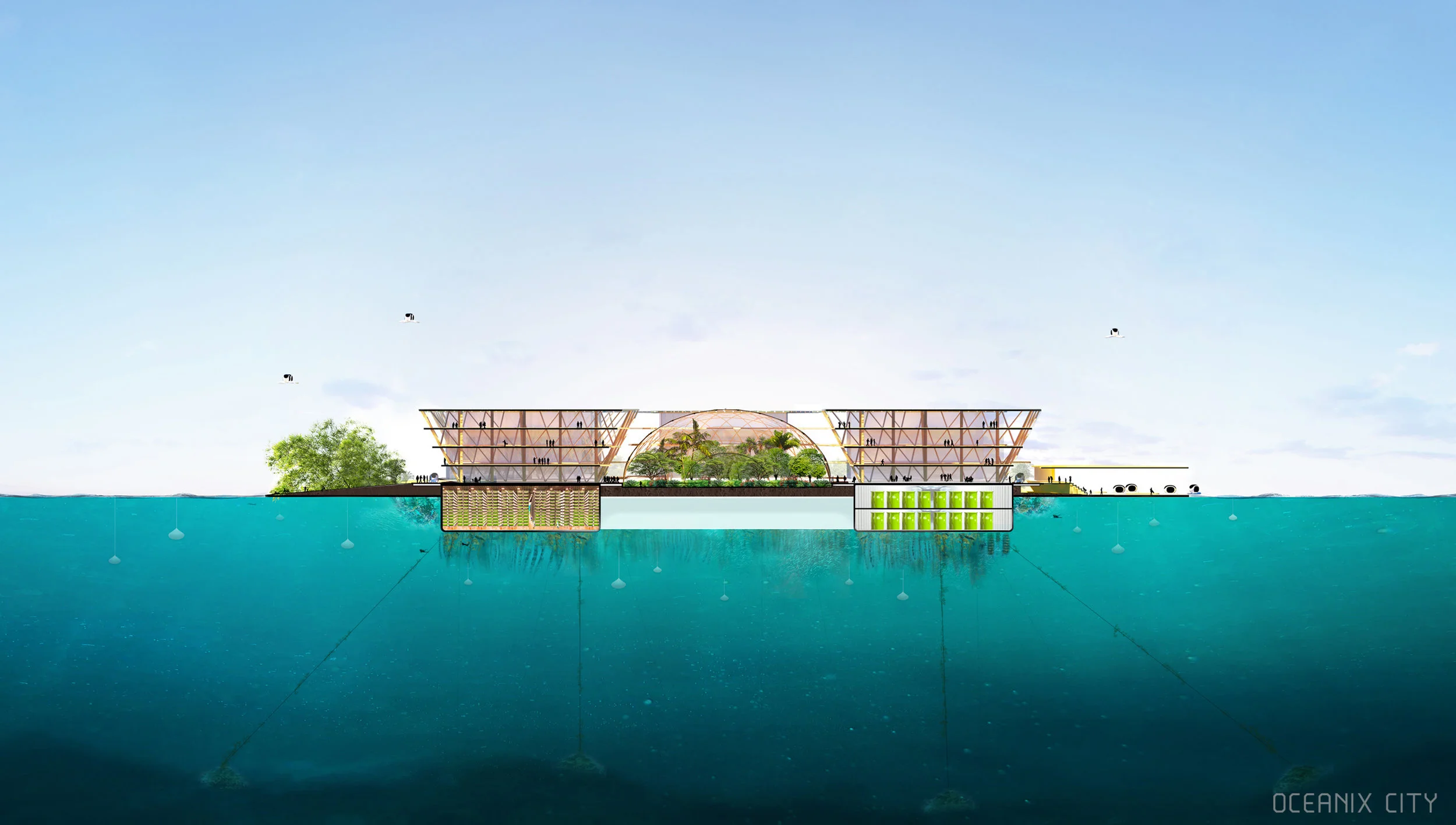

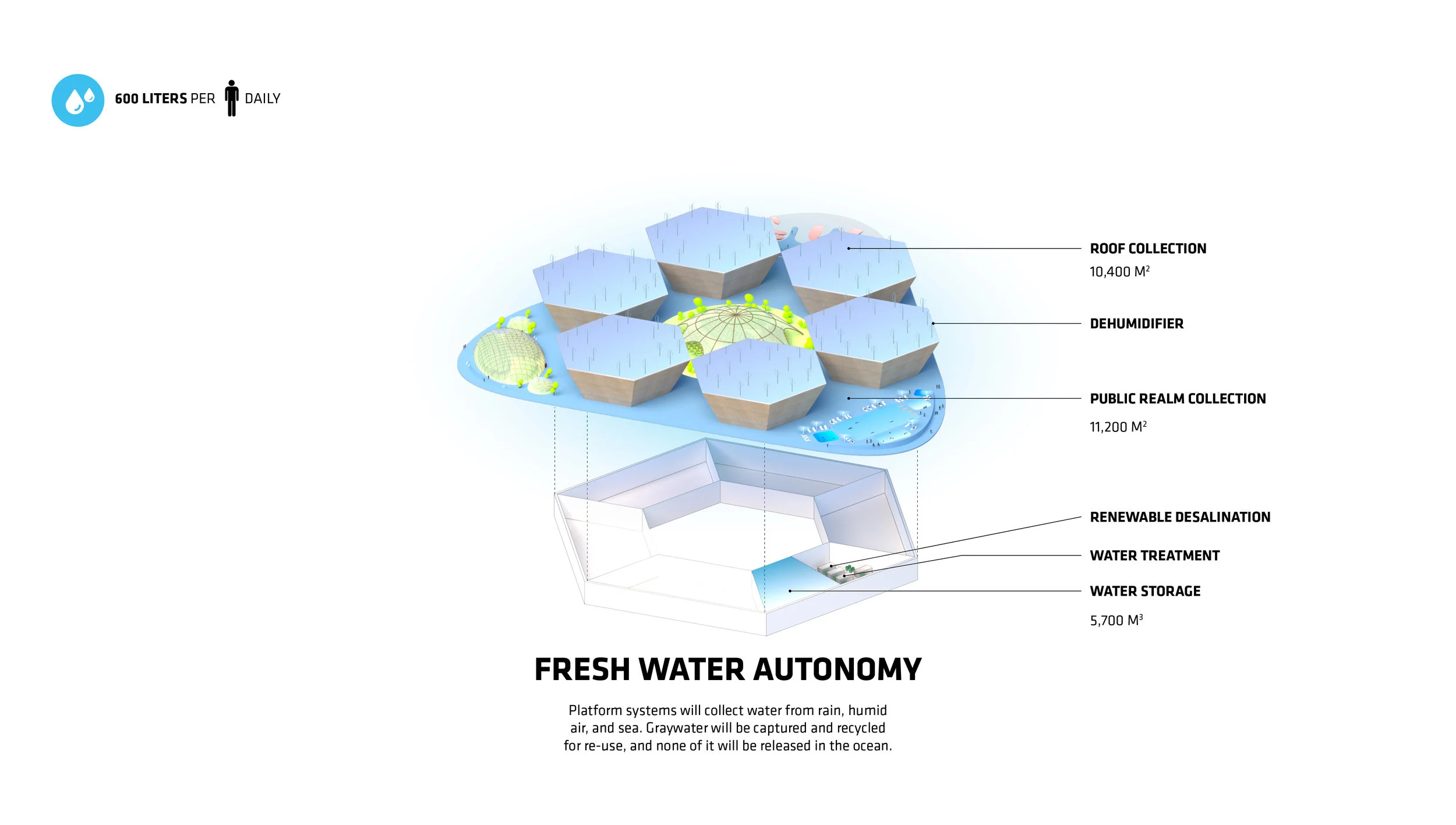

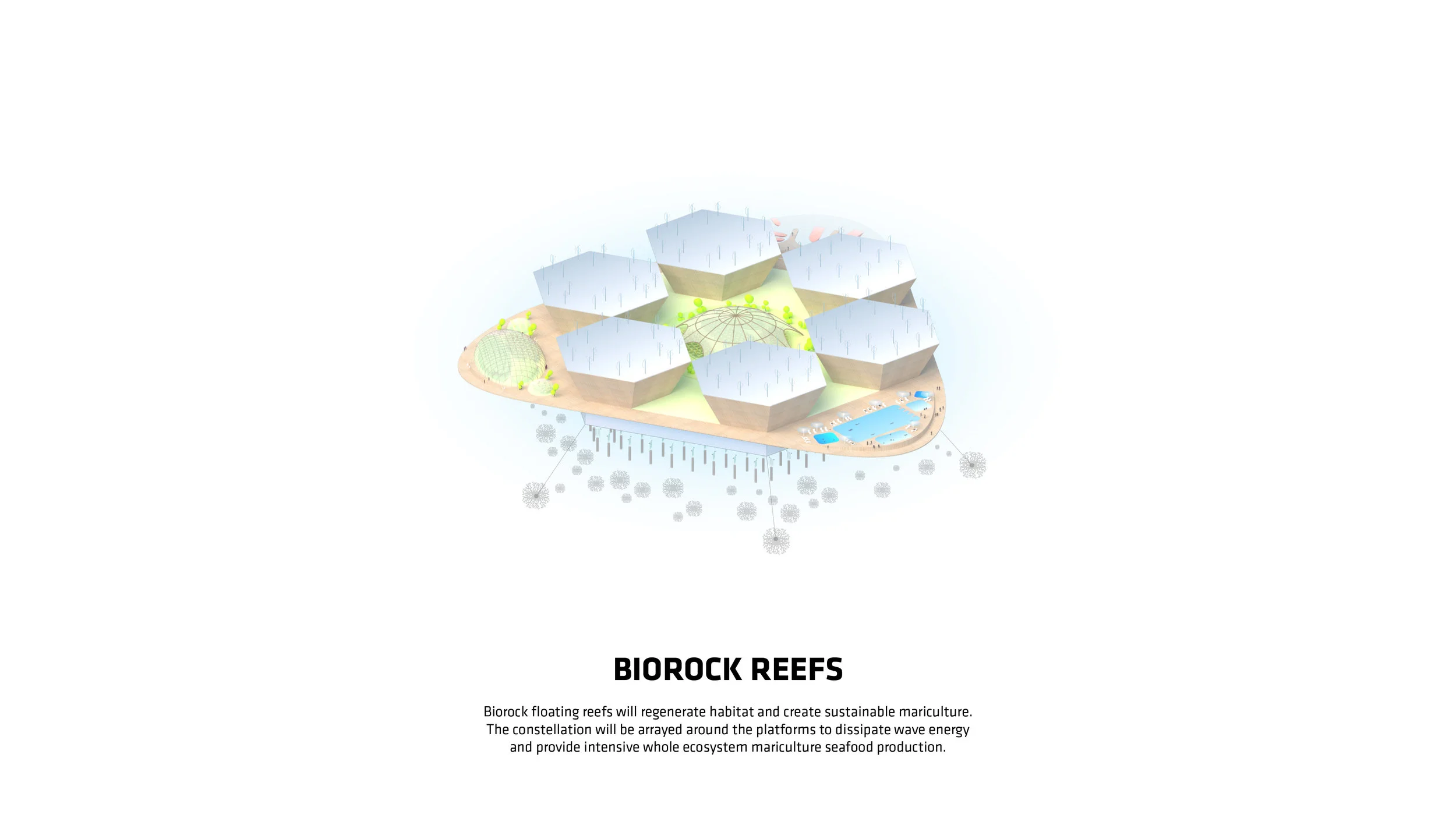

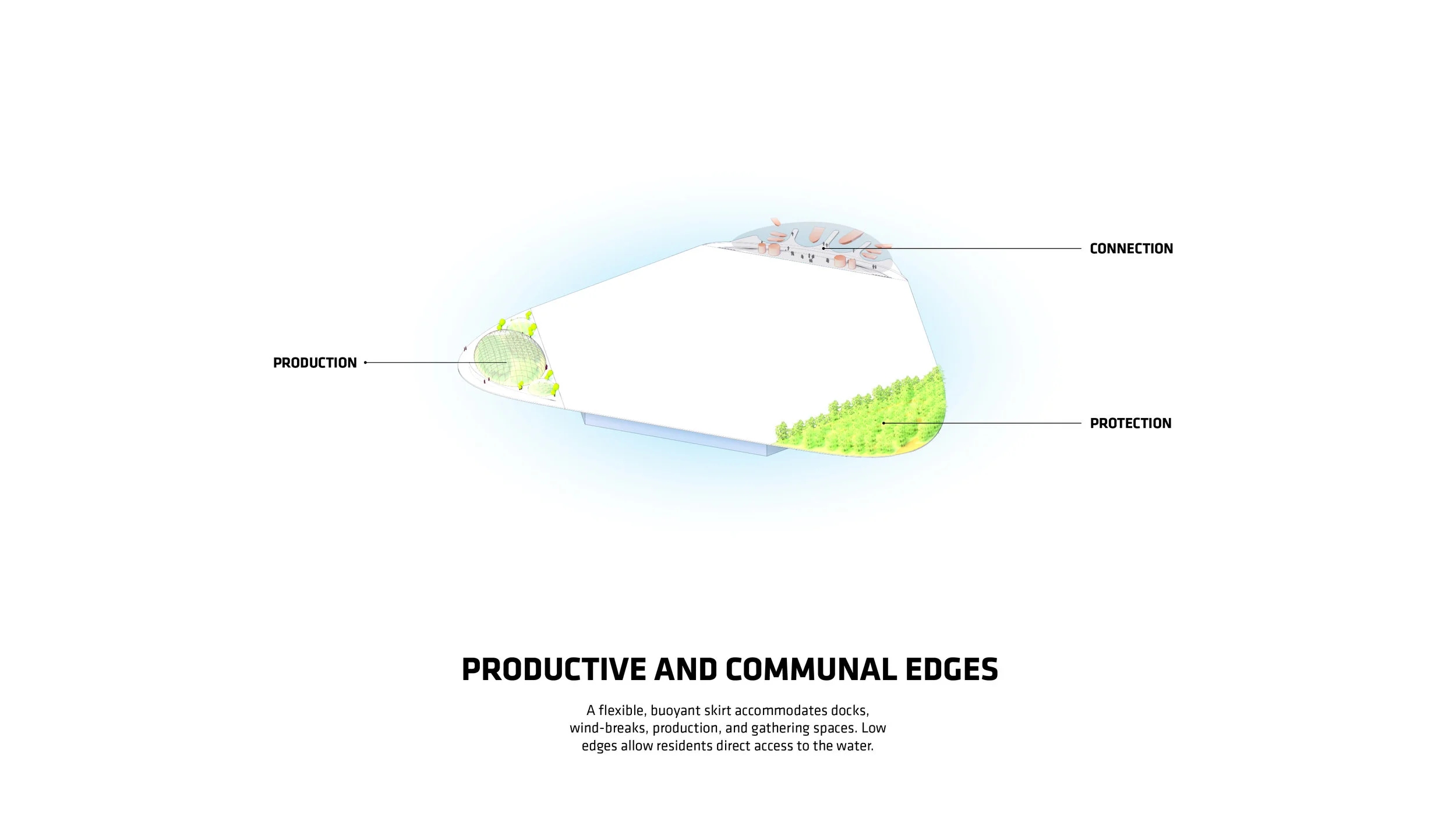

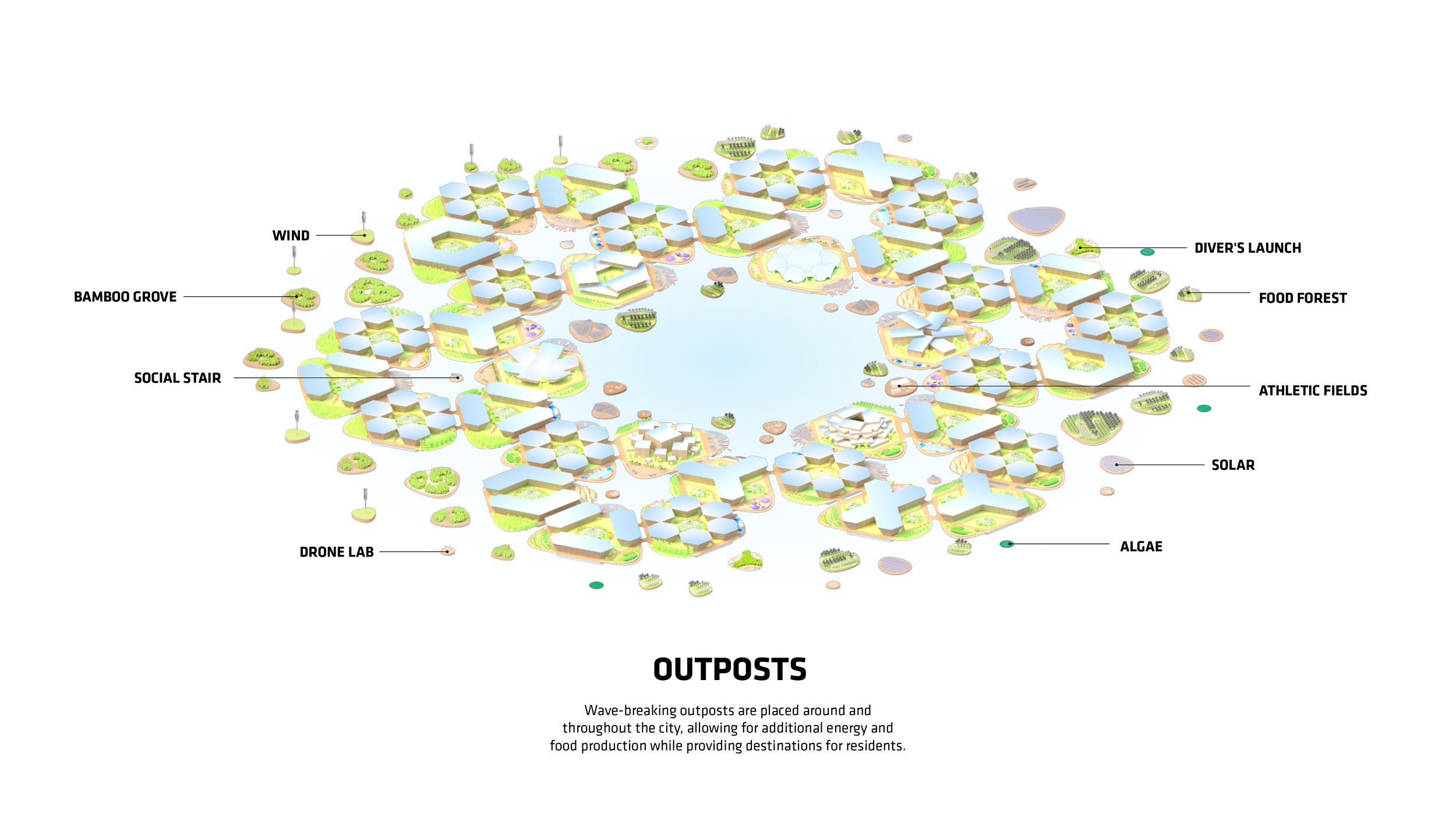

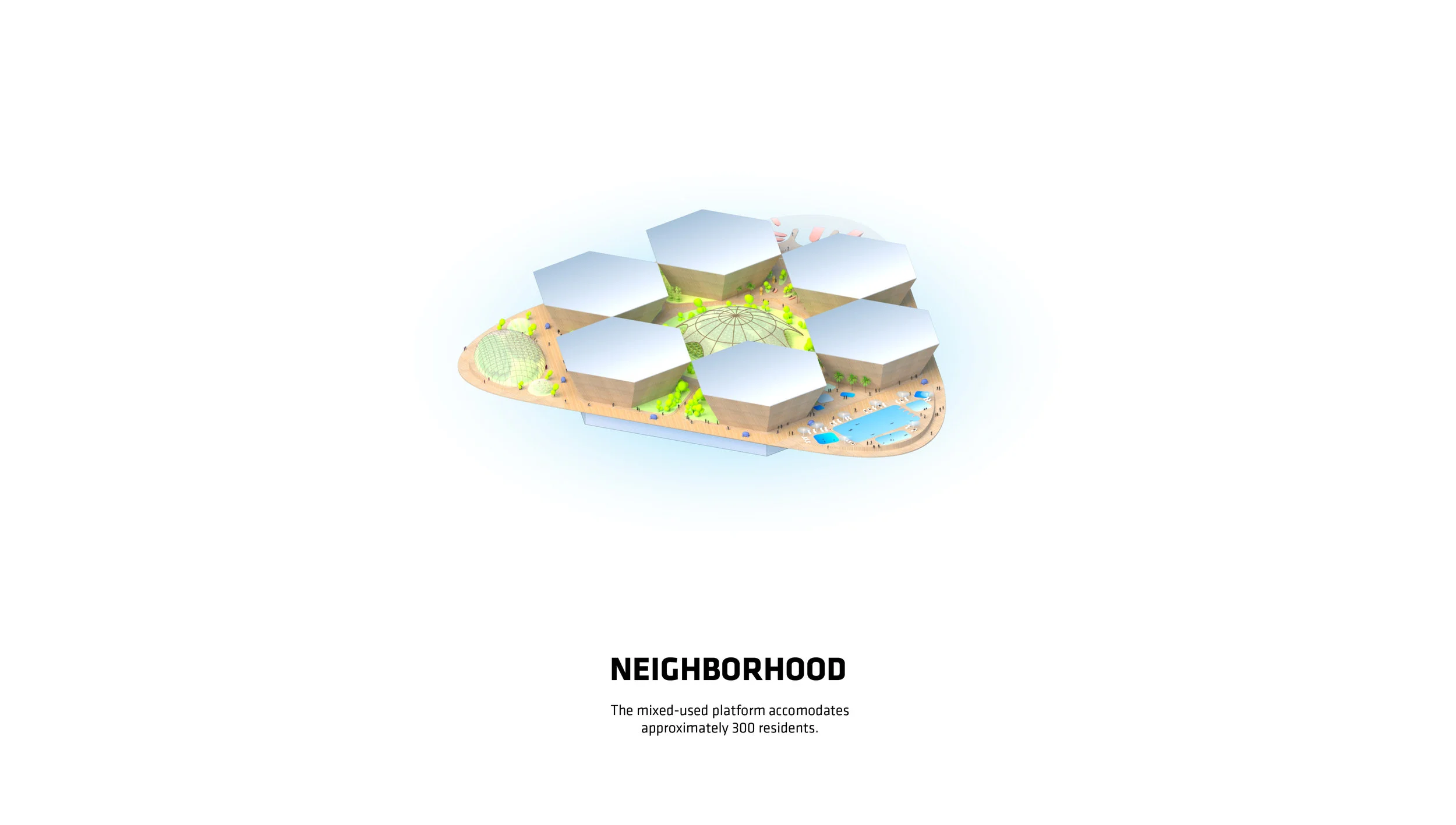

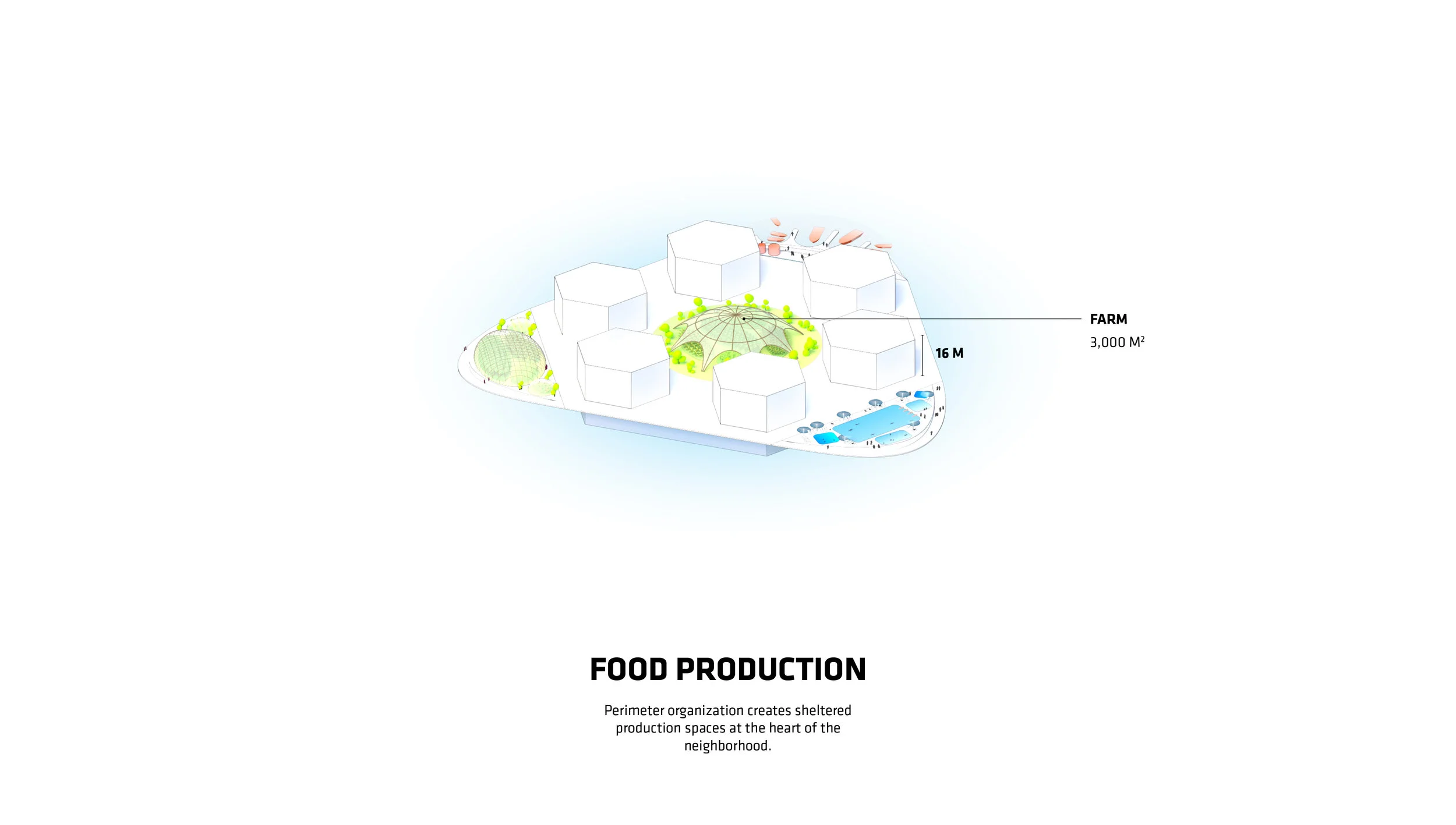

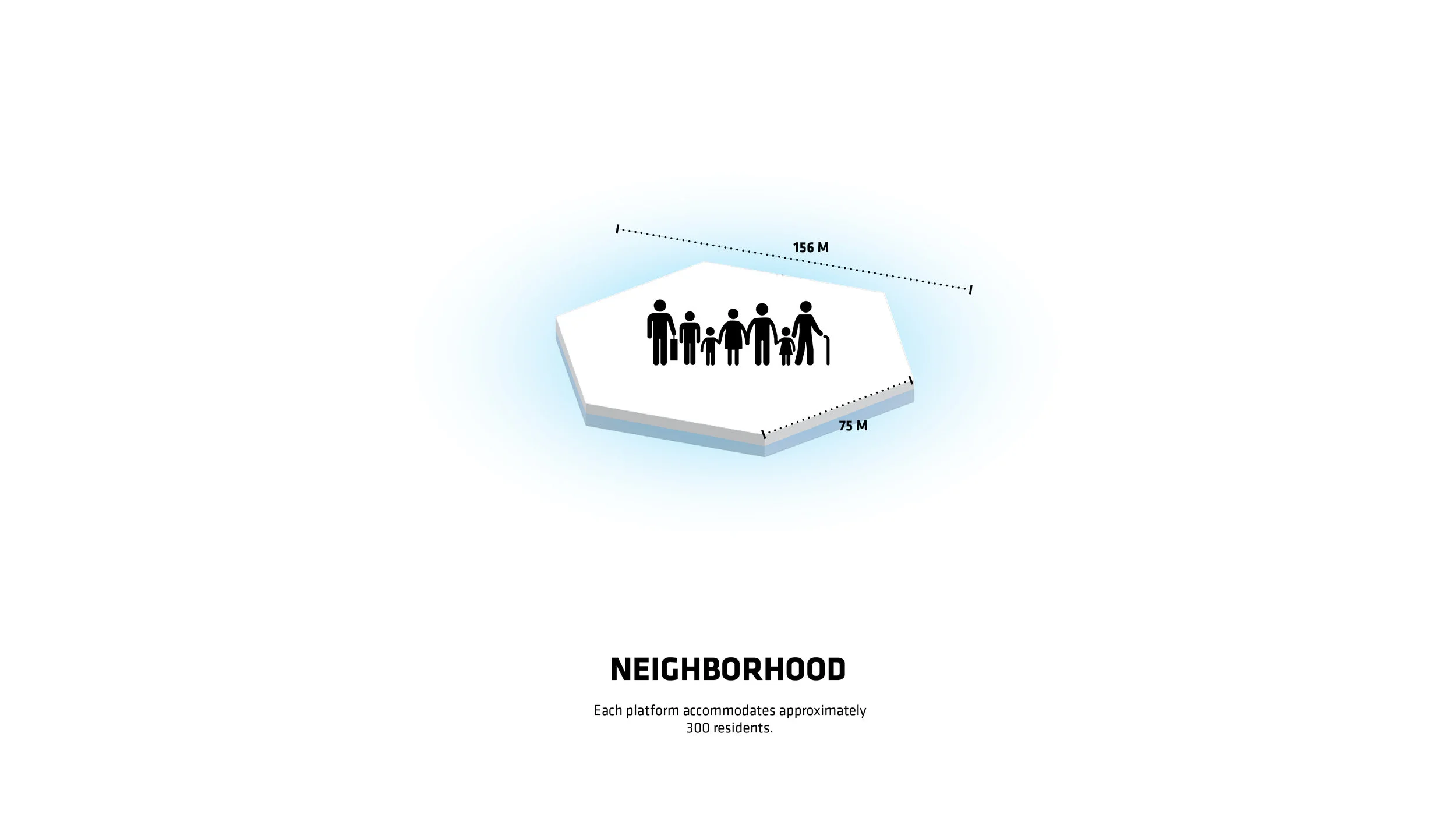

Oceanix City: This Concept Of Floating City Includes Food Production And Farming

Linked by Michael Levenston

“Every island has 3,000 square metres of outdoor agriculture that will also be designed so that it can be enjoyed as free space,” said Ingels.

By Katharine Schwab

Fast Company

Apr 4, 2019

Excerpt:

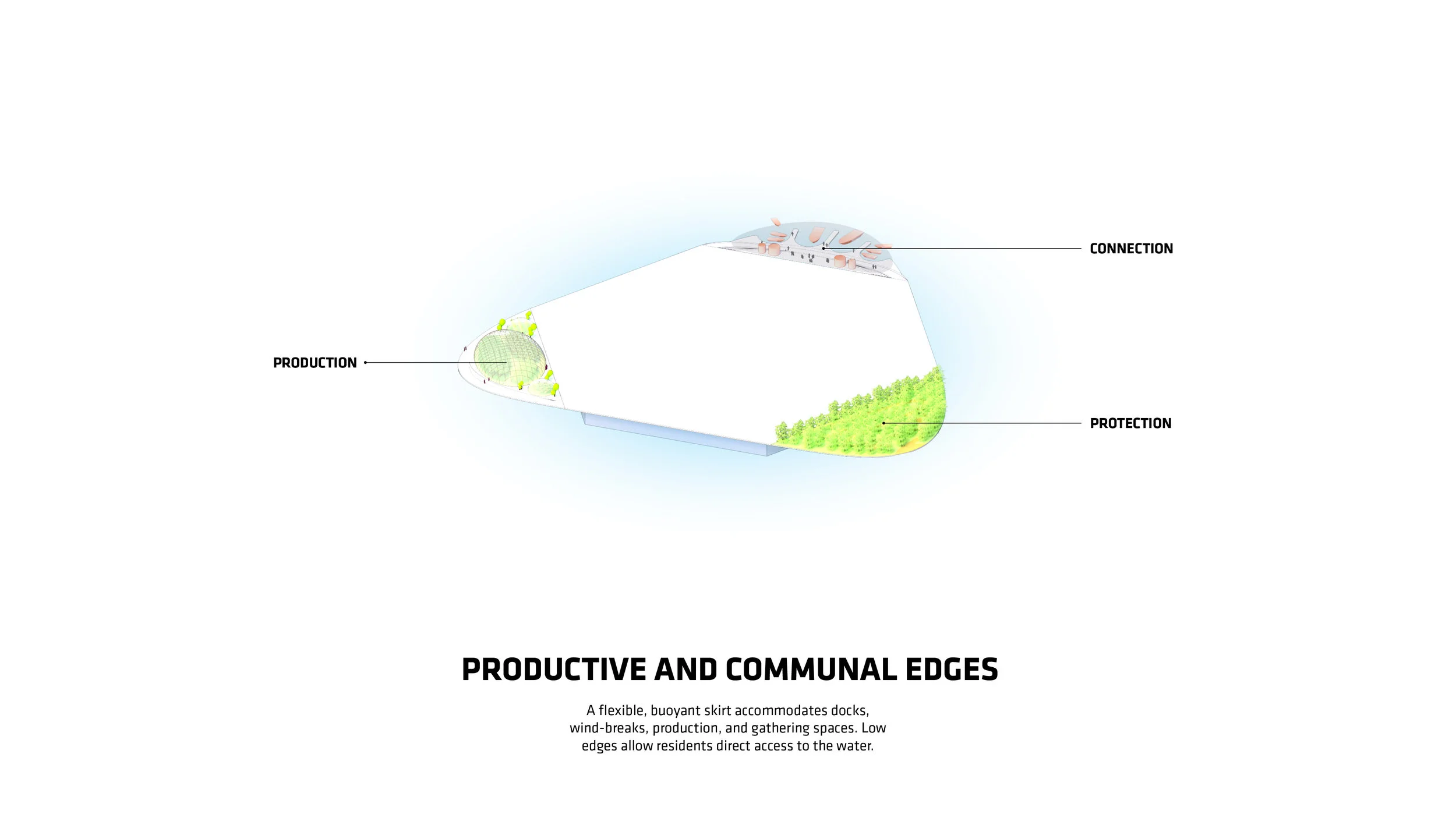

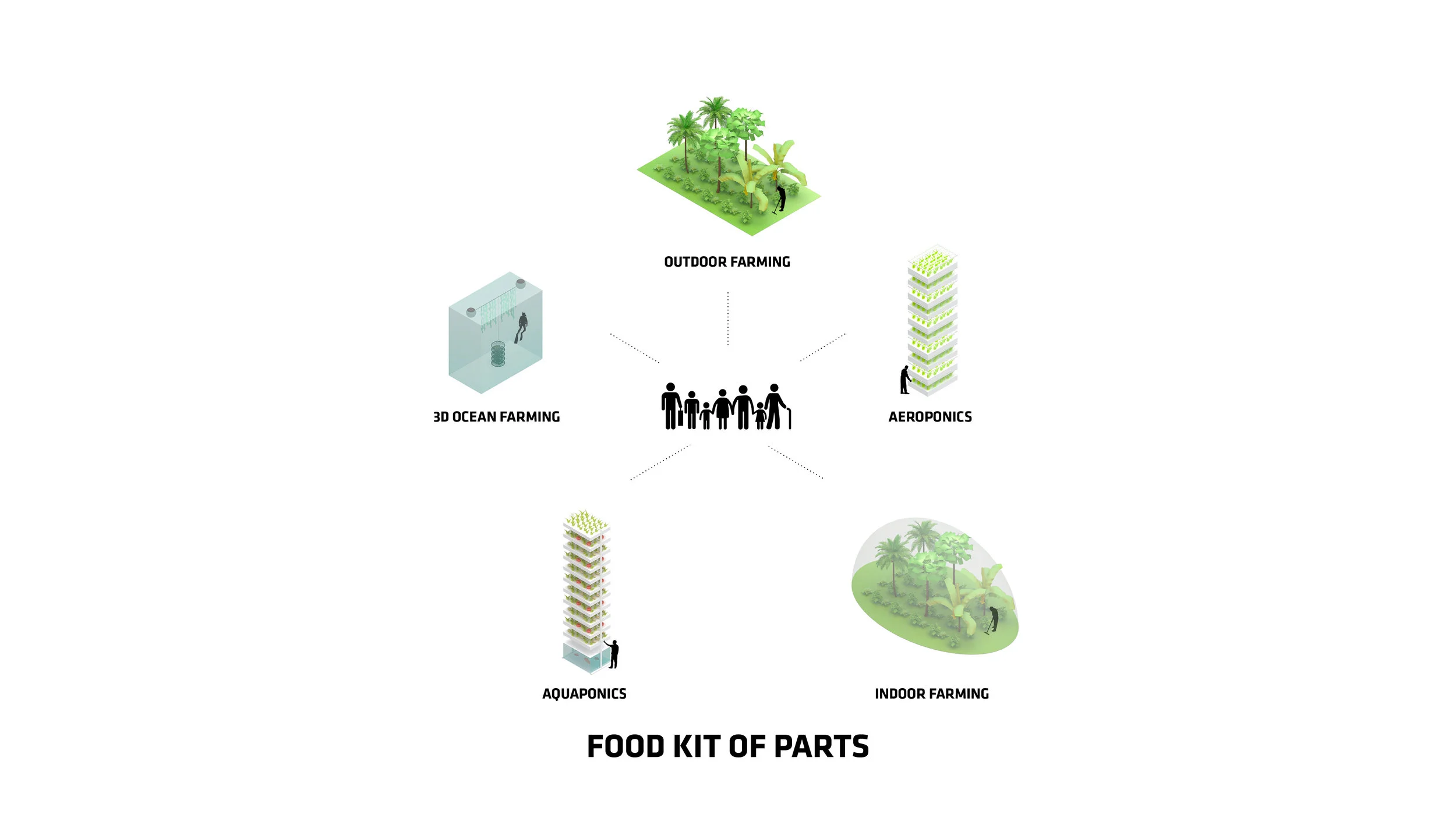

For Oceanix’s idea to work, all the food needed to feed every person living in the floating city would need to be grown there. What does that mean? There’s certainly no meat involved, mostly because beans are a far more efficient way of getting protein. Some crops would be grown outdoors–an estimated 32,000 square feet on each hexagon would be devoted to food cultivation. Much of that would be outdoors, since the sun uses the least amount of stored energy, and the crops would double as green space for residents.

But according to Clare Miflin, the cofounder of the Center for Zero Waste Design, a floating city would also need to experiment with other ways of growing food. One possibility: outdoor vertical farming for crops like lettuce. Then there’s hydroponics and aeroponics, the latter of which uses 10 times less water than traditional farming simply by spraying plant roots with mist. Aquaponics, in which plants grow hydroponically and are fertilized with fish waste, has a deep precedent–the Aztecs used aquaponic farming on their own floating agricultural islands many centuries ago.

With food comes food waste. Miflin wants to create a circular system where all food waste is turned into nutrients for the soil through composting. Food waste would go through a pneumatic system of pipes directly to an anaerobic digester to start the composting process. But there’s also the problem of packaging. Miflin believes that it would be crucial for the floating city to only use reusable food containers, with centrally located drop-off points for people to put their empty containers; from there, they could be cleaned centrally and reused.