Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

A Small Missouri Company Has Big Plans For Idle Elevators To Serve As Vertical Farms

A Small Missouri Company Has Big Plans For Idle Elevators To Serve As Vertical Farms

August 7, 2017

Vertical Innovations’ first vertical farm is planned for this elevator. Photos courtesy of Vertical Innovations.

By Ronald Ahrens

Jim Kerns and David Geisler called up the other day from Springfield, Missouri, to ask a question of our readers: Are you aware of any municipally owned, abandoned grain elevators?

Kerns and Geisler run Vertical Innovations, an enterprise formed in December of 2014 to repurpose old elevators, making them into incredibly productive vertical farms for growing leafy green vegetables. They have developed a patent-pending method of hydroponic production, a “structure-driven design” that adapts to the circular shapes.

“The silos tell us what to do,” said Kerns, who has a background in organic farming and leads the company’s innovation, design and construction efforts. “I see them as giant environmental control structures, giant concrete radiators.”

Significant energy savings can result from implementation of circular shapes, which among other things require far less lighting and the corresponding energy use, he said.

Jim Kerns explores elevator guts.

David Geisler, CEO and general counsel, has worked out a lease for a disused elevator in downtown Springfield.

For its next steps, the company has targeted an available elevator in South Hutchinson, Kan., and approached the owner of Tillotson Construction Co.’s Vinton Street elevator in Omaha.

“What an awesome facility,” Geisler wrote in a follow-up email, thinking of Vinton Street.

Geisler and Kerns have cast their eyes far beyond the Midwest, though, from big terminals in Buffalo, N.Y., to San Francisco’s threatened Pier 92.

“We really need to save that facility if it’s structurally sound,” Kerns said. “It could put out about 50 million pounds of green leafy vegetables per year.”

Their most unique discovery source is YouTube videos posted by those who have flown drones around elevators.

But word-of-mouth works, too, and Kerns issues this appeal to readers: “Submit to us pictures and locations of concrete grain terminals in good condition all across the United States, sea to shining sea, north to south.”

Vertical Innovations can be contacted through its website.

Food Security Issues & Innovations on the Table at September Urban Agri Summit in Johannesburg

Food Security Issues & Innovations on the Table at September Urban Agri Summit in Johannesburg

Press release from: Magenta Global Pte Ltd

Urban Agri Summit to be held in Johannesburg, South Africa on 7-8 September 2017

Africa's increasing concerns for food security to feed its growing populations and sustain economic development are to be tackled head-on by the region's foremost experts, regulatory authorities and various agriculture industry stakeholders at the Urban Agri Summit 2017 happening on September 7-8 in Johannesburg.

Several agri-sector leaders herald emerging innovative solutions such as vertical farming to address the continent's increasing need for an adequate and sustainable food supply.

"Vertical Farming will inevitably be Africa`s future pathway to food security and environmental sustainability," said Aliyu Abdulhameed, Managing Director for the Nigeria Incentive-Based Risk Sharing System for Agricultural Lending (NIRSAL). "NIRSAL`s participation in Urban Agri Summit 2017 will open new frontiers to better address the multidimensional needs of agricultural value chains in competitive urban agribusiness and food industry."

Prof Michael Rudolph, Director of the Siyakhana Multipurpose Cooperative, explained: "Vertical farming is becoming an important intervention for African cities as an innovative solution to supplying food, mitigating against air and noise pollution, applying water and energy conservation and combating urban food insecurity. Vertical farming will offer inner city children, youth and adults a chance to reconnect with nature and promote better environment health in the city. The Urban Agri Summit could not have come at a better time for Johannesburg as the city looks for innovative effective and efficient ways for addressing food and nutrition security as well as an environmentally healthy place to live. I look forward to robust discussions and networking with a wide range of key stakeholders during the Summit."

Mlibo Bantwini, Executive of the Dube AgriZone, added: "The agribusiness sector in Africa has tremendous potential to contribute to economic development and assist in ensuring food security. The use of methods such as vertical faming complemented with other methods of production can play a vital role in ensuring that this potential is fulfilled. We are excited to be part of the Summit. As this will be our first participation at the Summit, we hope to interact with many stakeholders and learn from their insights and build relationships with industry players."

Various initiatives have already been undertaken by South Africa to spur innovation in its agriculture sector. Together with other Sub-Saharan African cities in Nigeria and Kenya, South African metropolises are joining the footsteps of many global cities to introduce sustainable urban indoor farming. A key to sustainability, however, requires farms streamlining operations and reducing resource wastage.

"Food-producing agriculture value chains must undergo innovation to increase efficiency and yields, enhance variety, and meet the dietary demands of the growing population worldwide. To do so sustainably they must reduce waste and pollution, better manage and conserve water resources, and must be powered by renewable energy and energy efficient systems." said Nicole Algio, Regional Secretariat Manager for REEEP Clean Energy. She added: "REEEP as an endorsing partner to the Urban Agri Summit 2017, has a deep understanding of specialized research and analysis into the water-energy-food nexus and agrifood value chains globally, and supports climate smart innovation in agriculture such as vertical farming that applies the use of renewable energy and energy efficiency to reduce overall energy consumption of fossil fuels."

Angel Adelaja, Founder/CEO of Fresh Direct Produce & Agro-Allied Services, takes a fresh approach: “What if Africa no longer needed to import most of its food products, and agricultural value chains were strengthened, profitable, and were able to meet local demands for food without being environmentally tasking? This is my goal for my company Fresh Direct Nigeria and for African Agriculture. With increased urbanization, we need to secure our food systems not only rural agriculture, but with a complement of urban agriculture through technology and community. I'm excited that the Urban Agri Summit will be a gateway to unlock Africa's potentials through outside the box thinking.”

Urban Agri Summit 2017's is partnered by Gold Sponsor Nigeria Incentive-Based Risk Sharing System for Agricultural Lending (NIRSAL), and is supported by the Association for Vertical Farming (AVF) and by the Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Partnership (REEEP).

The two-day Summit will be held at the Sunnyside Park Hotel in Parktown, Johannesburg. For more details, contact Jose at +65 6846 2366 or email jose@magenta-global.com.sg.

Magenta Global is a premier independent multi-disciplinary business media company. We are committed to providing specialist, pragmatic and high-value information and knowledge to business executives and professionals worldwide. Helmed by a team with a combined industry experience of more than 50 years, Magenta Global is dedicated to equip businesses with research information, events, trade exhibitions, training solutions and peer-to-peer executive programs. We serve clients with a global portfolio of more than 100 events covering various verticals and geographies. Key focus areas are: Energy & Renewables; Telecoms & IT; Pharmaceuticals and Healthcare; Banking and Insurance; Business Management & Strategy; Agribusiness & Softs; Mining & Metals; Infrastructure & Investment; and Maritime & Trade.

In each of the sectors, Magenta Global organises training courses, specialist business forums and international conferences & exhibitions. Working in close partnership with both industry and governments, these events serve to provide cutting-edge information and a networking platform, acting as vehicles to promote investments, commerce and technology transfer.

Magenta Global Pte Ltd

Block 53 Sims Place

#01-150

Singapore 380053

Full Automation From Planning To Control For Indoor Farms Is Here

Full Automation From Planning To Control For Indoor Farms Is Here

Montreal, Canada | August 10, 2017

Two leading agtech companies have joined forces to offer award-winning automation software and hardware to indoor farms.

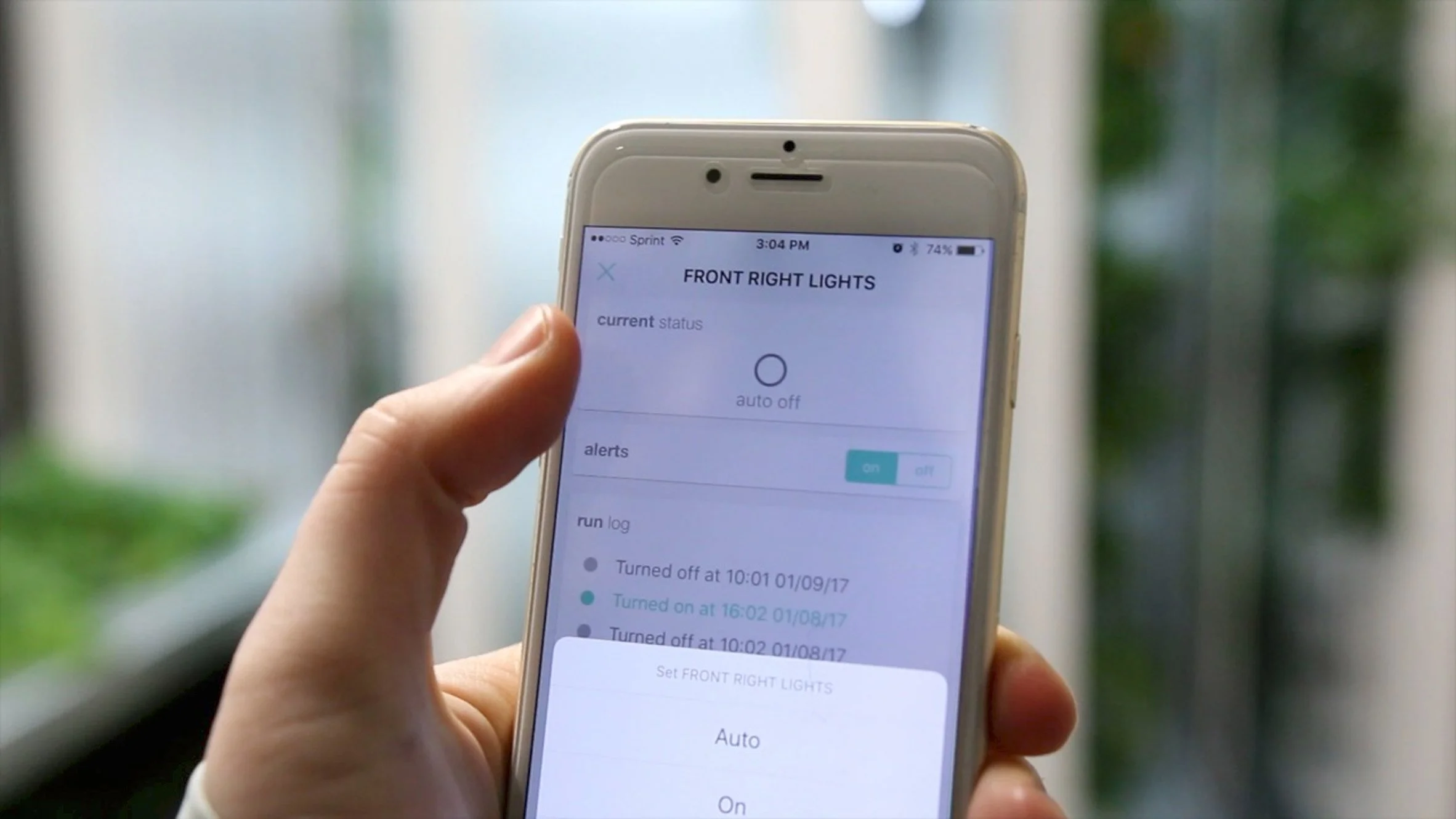

For the first time ever, growers will be able to use technology to automate processes that have previously been decided based on incomplete data.

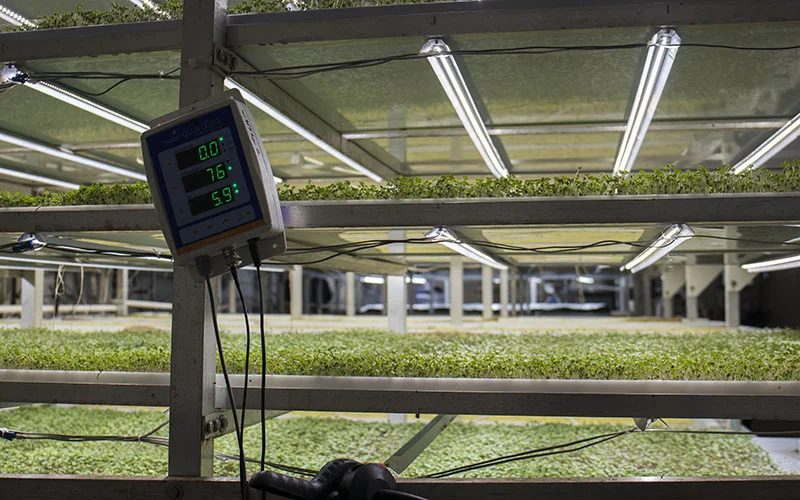

Motorleaf, based in Montreal, is the market leader in IoT, plug-and-play sensor, and controls hardware and software for hydroponic and greenhouse automation.

Agrilyst, based in Brooklyn, is the market leader in farm management and automation

software for indoor farms. It is now possible to connect Motorleaf devices to Agrilyst’s platform. Growers can visualize all of their climate and nutrient information real-time and alongside

their crop yield data.

“The customer is the most important piece of the puzzle, and facilitating easy

access to critical information in an intuitive and plug-and-play environment are

two of the things that both Agrilyst and Motorleaf customers already experience.

Now for the first time they can do this with both companies working together on

their behalf. Welcome to the new way agtech should work for all customers,”

says Ally Monk, Motorleaf Co-Founder and CEO.

“We believe the open exchange of data between systems is critical for farm

success and have always been committed to helping farmers access and utilize

their data in better ways. We’re excited to work with Motorleaf, who is quickly

becoming a key player in advanced indoor controls technology. Connecting to

top-of-the line devices will help our customers get the best insights into their

operations possible,” says Allison Kopf, Agrilyst Founder and CEO.

For a limited time, growers who sign up for an annual commercial farm

subscription with Agrilyst will receive two free hardware units from Motorleaf worth over $1400 USD.

Growers who are interested in taking the next step in data and automation can

sign up at: https://www.agrilyst.com/motorleaf

About Motorleaf

Motorleaf turns any greenhouse and indoor farm, into a smart connected

operation. From a hobby grower to 100+ acres of greenhouse; Motorleaf has a

suite of hardware and software to allow the Monitoring, Automation, and

AI/Machine Learning enabled discovery to flourish. Motorleaf allows all farmers to

‘Sleep Well <while plants> Grow Well.’Sleep well, grow well,

About Agrilyst

Agrilyst is the virtual agronomist powering the horticulture industry. The company

was founded in 2015 and is based in Brooklyn, NY. The subscription-based

software helps growers automate labor-intensive processes like production

planning, crop scheduling, and task management and drive higher revenues on

the farm. Agrilyst is committed to helping every indoor farmer reach profitability.The Motorleaf Team!

Contact: Alastair Monk - Motorleaf CEO | monk@motorleaf.com

The Heartland Is Fertile For Ag Tech, But California Is Still King

Last month, San Francisco-based indoor farming startup Plenty scored a win for the California ag tech scene when it secured a $200 million investment from SoftBank’s Vision Fund, one of the largest rounds ever for an ag tech startup.

Image Credit: Pixabay

The Heartland Is Fertile For Ag Tech, But California Is Still King

ANNA HENSEL@AHHENSEL AUGUST 10, 2017 10:30 AM

Last month, San Francisco-based indoor farming startup Plenty scored a win for the California ag tech scene when it secured a $200 million investment from SoftBank’s Vision Fund, one of the largest rounds ever for an ag tech startup. With $2 billion invested in California ag tech startups since 2010, it’s not surprising that California is the most promising place for ag tech — it’s the state with the largest agriculture sector by cash receipts, according to the USDA. But new data from Pitchbook indicates that other states with strong farming sectors are still having trouble cashing in on ag tech.

The good news: Among the 10 states that receive the most ag tech funding are Heartland states like Missouri, Michigan, and Illinois. The bad news: Ag tech startups in California received more funding from January 2010 to June 30, 2017 than all ag tech startups in the other top 10 states for ag tech combined during that same time period. And states like Iowa, Nebraska, and Minnesota — the states with the second, third, and fifth largest agriculture sectors respectively — are nowhere to be seen.

Rob Leclerc, the cofounder and CEO of Agfunder, an online investment platform for ag tech startups, explains that just as in any other sector, ag tech startups have to consider what city will put them in close proximity to their customers, venture capitalists, and good talent before deciding where to place their headquarters. Though states like Iowa and Nebraska have larger agriculture sectors and thus offer ag tech startups closer proximity to more customers, states with smaller, yet still prominent, agriculture sectors like Illinois and Michigan are home to more large universities and cities — and thus larger talent pools, as well as more corporations to potentially partner with.

Jesse Vollmar, the cofounder and CEO of FarmLogs, a startup that provides crop management software to farmers, decided to set up its headquarters in Ann Arbor, Michigan after participating in Y Combinator’s accelerator program in 2012. They settled on Michigan because both Vollmar and his cofounder, Brad Koch, are from there. Additionally, Ann Arbor, home to the University of Michigan, offered FarmLogs close proximity to talent, as well as a major airport that Vollmar and Koch could reach quickly.

“We considered Chicago, but we just didn’t have an established network there,” Vollmar says. “It’s not located in as close proximity to farmers.”

While a high concentration of ag tech funding in California is great for the state, one concern is that it could lead to a lack of diversity in the types of problems that new ag tech startups look to solve.

“If you look at California, there’s a lot of local talent that allows you to solve sort of different types of problems — problems around robotics, around automation. The problems that farmers here often have are specifically around labor,” Leclerc explains. “If you go to the Midwest, what you’re dealing with is much much larger farms; the farms are often so big that you can’t possible go and survey them all entirely, so you really have a big data problem.”

While ag tech startups in places like Iowa and Nebraska may be lacking funding, there’s still plenty of enthusiasm to cultivate a large ag tech sector there. Last year marked the opening of a new ag tech accelerator in Iowa, called the Iowa AgriTech Accelerator, which secured investments from companies such as John Deere and DuPont.

Urban Farm Grows Ugly Greens In Brooklyn, NY

Urban Farm Grows Ugly Greens In Brooklyn, NY

Good greens don’t have to ‘look’ pretty. Even ‘ugly’ produce is just as delicious. This is something Gotham Greens has discovered through its recent Ugly Greens movement. What may have once been considered unmarketable produce was enjoyed by the staff at work or home instead. “We’d enjoy them as part of a team meal and staff would take them home to eat,” explains CEO, Viraj Puri. “But we realized there was an opportunity to sell them while helping to bring attention to the issue of food waste. The amount of food waste in this country is staggering and the NRDC estimates that as much as 50% of produce is thrown out between the farm and the fork.” They’re hoping to show people that slightly blemished greens can be perfectly nutritious, fresh and local despite their cosmetic flaws. “By embracing cosmetically-challenged produce as beautiful, we’re hoping to play a small role in reducing food waste,” he adds.

Food is wasted for cosmetic reasons

Food waste is a concerning issue for consumers, something all retailers and growers should keep top of mind. Puri says that in the US over 70 billion pounds of food is wasted each year which amounts to 250 pounds per person. “Much of what’s discarded is done merely for cosmetic reasons or as a result of long distance transportation. This negatively impacts farmers, retailers and ultimately consumers.” Changing consumer’s preferences towards slightly blemished or imperfect fruits and vegetables is an additional way to address the issue. Feedback on Gotham’s program has been overwhelming, according to Puri and even though it’s a small part of their production and overall business, they’re excited to see the positive feedback.

Current greens being grown and harvested include about a dozen varieties of leafy greens, arugula, and basil. And, supply is good. “Our current production is very strong,” he says. “We’re able to offer our customers a very reliable and consistent supply of greens all year round.”

Year-round availability

Gotham Greens stands by its model of urban agriculture, something Puri says is appreciated by chefs and retail produce buyers. “We grow premium quality local produce in high tech, climate controlled greenhouses, year round. That means, even in the dead of winter, we provide our customers— supermarkets, restaurants, caterers—with fresh produce within a couple of hours of harvest.” Produce is pesticide-free, grown using ecologically sustainable methods in 100% clean, electricity-powered greenhouses. He says this also results in providing precision plant nutrition and optimal growing conditions for the plants. “Hydroponic farming, when practiced effectively, can be very efficient, using a fraction of the amount of resources as traditional farming practices. This enables us to use one tenth the amount of water as traditional soil based practices, while also eliminating all agricultural runoff.”

There may be plans of expansion in the works. Gotham Greens has several new projects planned which could bring urban farming to other cities across the US and globally. “We have several new projects in the works and look forward to sharing more information about them in the coming months.”

For more information: Viraj Puri | Gotham Greens

Publication date: 8/8/2017

Author: Rebecca D Dumais

Copyright: www.freshplaza.com

Urban Hydroponic Farms Offer Sustainable Water Solutions

Urban Hydroponic Farms Offer Sustainable Water Solutions

At Local Goods in California, Ron Mitchell’s monitoring system checks the plants’ water supplies for temperature, pH levels and electric conductivity. (Photo by Jackie Wang/News21)

By Nicole Tyau | News21 Tuesday, July 11, 2017

BERKELEY, Calif. – Tucked behind a Whole Foods in a corner warehouse unit, Ron and Faye Mitchell grow 8,000 pounds of food each month without using any soil, and they recycle the water their plants don’t use.

Hydroponic farming grows crops without soil. Instead, farmers add nutrients to the water the plants use. This method can produce a wide variety of plants, from leafy greens to dwarf fruit trees.

According to a study by the Arizona State University School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, hydroponic lettuce farming used about one-tenth of the water that conventional lettuce farming did in Yuma, Ariz. A similar study from the University of Nevada, Reno, found that growing strawberries hydroponically in a greenhouse environment also used significantly less water than conventional methods.

(Video by Jackie Wang/News21)

The Mitchells started production of Local Greens in February 2014. They primarily grow microgreens such as kale, kohlrabi and sprouted beans while using the same amount of water as two average households and the same amount of electricity as three in a month, they said.

“Who knows what you’re getting when you’re using soil?” Faye said. “Hydroponics is a fully contained system, so we know exactly what’s in our water, what we want in it and what we don’t want in it, and we can control that.”

Ron installed a water filtration system he customized. He removes fluoride, a common additive in municipal water, and chlorine, a common disinfection byproduct, before adding oxygen and other plant-specific nutrients.

At Local Greens, Ron and Faye Mitchell mostly cultivate microgreens, which grow to about 10 inches before they are cut and sold in the area. (Photo by Jackie Wang/News21)

To make use of the warehouse’s tall ceilings, the Mitchells stack six trays of microgreen seeds on top of each other. At one end, an irrigation spout controls the amount and type of water sent through the trays.

“Some plants don’t need or want nutrients because they have it in their seed,” Ron said. He explained that pea shoots don’t need any additives, but sunflowers require copious amounts of nutrients to grow quickly.

Ron Mitchell, 67, said the stacked trays inside his hydroponic farming facility in California allow them to grow twice as much. (Photo by Jackie Wang/News21)

The water the plants don’t use is captured at the other end of the tray and reused for the next watering, with the nutrients replenished as needed. The additional nutrients in the water are organic and naturally-occurring since they don’t have to spray pesticides or herbicides in their controlled warehouse environment, Faye said.

The number of greenhouse farms has more than doubled since 2007, according to the 2012 U.S. Department of Agriculture Census of Agriculture. Some hydroponics advocates see the practice as a solution to a global food and water crisis.

“I don’t think it could take over the farming industry entirely because of the types of plants and vegetables people want to eat,” Faye said. “But I definitely think it could make a dent in the farming industry and make its place and replace certain types of farms for a more efficient and, in some cases, less expensive system.

Editor’s note: This story was produced for Cronkite News in collaboration with the Walter Cronkite School-based Carnegie-Knight News21 “Troubled Water” national reporting project scheduled for publication in August. Check out the project’s blog here.

Downtown Restaurants Growing Ingredients Right On-Site

Downtown Restaurants Growing Ingredients Right On-Site

By Todd Lihou | August 10, 2017

Michael Baird, left, of ESCA Gourmet Pizza + Bar, and Eric Lang of Zipgrow Canada, in front of the farm wall located on the ESCA patio.

CORNWALL, Ontario – A pair of downtown restaurants have partnered with a local firm to offer fresh products grown right on-site for hungry customers.

That’s right – the food is being grown on-site…in some cases right beside your table.

Truffles Burger Bar and ESCA Gourmet Pizza + Bar have partnered with Zipgrow Canada and installed a farm wall at each location.

The self-contained vertical gardens are currently growing kale and basil, which is used in food-preparation at both restaurants.

So far the response from patrons has been two thumbs up.

“Our kitchen love it, the staff love it and when we pick from it customers ask about it on the patio,” said ESCA’s Michale Baird. “And it’s fresh.

“The first pesto we made with it, the response was incredible. And it was stuff that grew 20 feet away from where it was being prepared.”

Eric Lang of Zipgrow Canada said his company, which specializes in small systems to grow in your home as well as full-scale commercial farms for warehouses, said the items grown in the farm walls can be customized and tailored depending on the time of year and foodstuffs being prepared.

“We can put in some of the vegetables that like it a little cooler. We can go right up until it is frosty,” he said. “We sell all over the world, but we are from Cornwall and we love these kinds of partnerships locally.”

Stop by Truffles and ESCA this summer and fall to enjoy some delicious offerings made with products grown right on-site.

Freight Farms Allows Crops To Be Grown Inside Shipping Containers

Freight Farms, a startup that has found a way to grow crops inside shipping containers, features in the latest video in our Dezeen x MINI Living series.

Calum Lindsay | Published 08-11-17

Freight Farms, a startup that has found a way to grow crops inside shipping containers, features in the latest video in our Dezeen x MINI Living series.

The organisation has developed a hydroponic farming system called The Leafy Green Machine. It uses this hi-tech growing technology to transform discarded freight vessels into mobile farm units.

Each farm occupies 320 square metres of space, but Freight Farms claims that each one can produce as much food as a two-acre plot of land.

Inside, seeds are planted in trays and exposed to LED grow lights until they sprout. The seedlings are then transplanted into vertical hydroponic planters, and fed nutrient-rich water from ceiling spigots that flow into artificial root systems.

In order to monitor and manage conditions inside the farm, Freight Farms has produced a smartphone app called Farmhand. Lighting, temperature, humidity and carbon dioxide levels inside the farm can be controlled remotely using this app.

This technology-based approach towards food production is known as controlled-environment agriculture (CEA). The benefit of this approach it that isn't affected by climatic and seasonal factors – one of the biggest limitations on traditional farming.

Freight Farms claims that its system enables food to be produced throughout the year in any location, as the outdoor climate has no impact on the conditions inside the shipping container.

The project taps into the growing trend for urban farming, which has seen an influx of investment and innovation in recent years, and is set to continue, as the proportion of people living in cities is growing exponentially.

According to Freight Farms, CEA systems could become commonplace in urban areas. City farmers would be able to expect plentiful harvests from a year-round growing-season, which would benefit urban communities lacking access to fresh local produce.

Freight Farms also claims that its fusion of technology with vertical farming has the ability to reduce the ecological footprint of food production, as its farms are able to produce food on a considerably smaller plot than is required by traditional crops.

Some restaurants, like B Good in Boston, have already installed Leafy Green Machines on-site, giving them immediate access to fresh and inexpensive produce.

Meanwhile, NASA has offered a grant to Freight Farms and Clemson University to develop off-the-grid farming systems using renewable energy, so that the space agency would eventually be able to adapt the technology to provide life support on Mars.

This movie is part of Dezeen x MINI Living Initiative, a year-long collaboration with MINI exploring how architecture and design can contribute to a brighter urban future through a series of videos and talks.

Read more

This Company Wants to Bring Soil-Free Farming to Restaurant Kitchens

Hydroponics have allowed garden vegetables to grow in novel places—from a pillar inside a Berlin grocery store to a veritable skyscraper of plants in Singapore.

This Company Wants to Bring Soil-Free Farming to Restaurant Kitchens

by Cathy Erway • 2017

Hydroponics have allowed garden vegetables to grow in novel places—from a pillar inside a Berlin grocery store to a veritable skyscraper of plants in Singapore. The fast-growing, soil-free farming method has been well-embraced in urban areas to produce crops using less water and space, since the plants are grown in a nutrient water solution, rather than in-ground. But rarely is it done within some of the buzziest places for the farm-to-table movement: a restaurant.

The team behind Farmshelf hopes that will soon change, and recently debuted three indoor hydroponic growing units at Grand Central Station’s Great Northern Food Hall. There, the chefs at the busy food market’s Scandinavian restaurant Meyers Bageri reach into the glass-walled cubicles to pick lemon basil for a garnish on their zucchini flatbread, and nearly a dozen varieties of baby lettuces are plucked for salads at the neighboring Almanak vegetable-driven café. And, as it would appear on recent visits, curious bystanders peer through the glass, agape at the billowy mixture of herbs and greens, illuminated by a ceiling of LEDs. Unbeknownst to the casual observer, the units are also outfitted with five cameras along every shelf, so that the Farmshelf team can monitor the plants’ progress from afar and adjust the system via a web application.

“The more plants we grow, the smarter we are about plants,” said Jean-Paul Kyrillos, Farmshelf’s Chief Revenue Officer. He explained that through their data collection, Farmshelf can optimize the growth and flavor of any plants that a client may want. “This is for someone who doesn’t want to be a botanist, or farmer. The system is automatic.”

“Plants can grow two to three times as fast using 90% less water than traditional in-ground farming”

That’s why Farmshelf hopes its units will be a boon for restaurants serving greens galore. Founded in 2016 by CEO Andrew Shearer, Farmshelf is just planting its roots in the New York City restaurant industry with its first partner, Meyers USA hospitality group. The startup was in the inaugural lineup of the Urban-X accelerator and is part of the Urban Tech program at New Lab. The company is looking to partner with more restaurants soon, and Kyrillos mentioned a restaurateur who was excited about the idea of placing a Farmshelf unit right in the dining room, as a partition.

Distribution is the last challenge of getting local food onto plates, and Farmshelf eliminates that entire process—no middleman, forager, or schleps to Union Square Greenmarket. Kyrillos is hopeful that the efficiency of hydroponics—where plants can grow two to three times as fast using 90% less water than traditional in-ground farming—will also convince restaurants of the value of placing such a system on-site. Then, there is the potential of growing ingredients that you could never get locally, like citrus; or mimicking the terroir of, say, Italy, through a special blend of nutrients and conditions within the units.

Green City Growers in Cleveland, OH, has a 3.25-acre hydroponic greenhouse. Photo by Flickr/Horticulture Group

With hydroponics, you can grow a plethora of vegetables, even root vegetables like turnips, carrots, radishes, but these take much longer, and thus not suited to the fast-paced restaurant environment Farmshelf is trying to service. Crops that take up a lot of space, like watermelon and pole beans, are also not ideal, as the point is for these systems to use space efficiently (though future designs of hydroponic units might be able to tackle this challenge). It's most cost-effective to grow delicate, highly perishable, expensive leafy greens than roots, which are quick to grow and easy to ship and store.

The possibilities seem endless. But, in an age when the small family farm is rapidly disappearing in the US—and faces further threat from a recent White House budget proposal that would eliminate crop insurance—would this technology take away business from local farms, which restaurants might otherwise buy from?

Hydroponics—The Future of Farming in Detroit?by Lindsay-Jean Hard

Kyrillos doesn’t see Farmshelf as a replacement for the local farmer. There are some six to eight months of the year where traditional farms can’t grow too many crops, so restaurants would buy leafy greens and other warm-season produce elsewhere. If anything, Kyrillos posited that it might chip away at business from some of the bigger food distributors.

But time will have to tell what best works for the soon-to-be users of Farmshelf. Right now, the company is hoping to sell restaurants at least three growing units to make a significant enough impact on its kitchen orders. Rather than leaving it at that, Farmshelf wants to work with restaurants through a sort of subscription-based service, supplying seeds for crops that the restaurant would like to grow and monitoring the growing process consistently. Could a chef go rogue, and use the unit to plant and harvest whatever, whenever he pleased? Perhaps—but that wouldn’t really be taking advantage of the full product, which the team estimates might cost around $7,000 per unit (a medium-sized restaurant might need three units, at $21,000), which would pay off in ingredient costs.

And how about home chefs? When will average consumers be able to place Farmshelf inside our cramped, outdoor space-free apartments? That’s in the vision for Farmshelf someday. Not just homes, but school classrooms or cafeterias could be future sites of these hydroponic shelves, Kyrillos suggested, offering an easy, indoor way to connect youngsters to the food on their plates. “Imagine children were watching food grow, all the time.”

TAGS: HYDROPONICS, TECHNOLOGY, ENVIRONMENT, GRAND CENTRAL

Shenandoah Growers Opens Texas Indoor Production Facility

Shenandoah Growers Opens Texas Indoor Production Facility

July 13 , 2017

Virginia-based organic culinary herb grower and producer Shenandoah Growers (SGI) claims it is “set to transform the distribution of highly perishable produce”.

Through a proprietary combination of automated greenhouses and indoor LED vertical grow rooms to produce more than 30 million certified organic plants per year, SGI has now brought a third indoor growing facility online.

The new facility, located in Texas, is the latest component of SGI’s innovative hub-and-spoke farming and distribution system, and only the most recent step in the company’s three-year, multi-million-dollar nationwide expansion of indoor farming.

The group claims the system is quickly scalable for market growth, allowing Shenandoah Growers to “locally deliver certified organic superior flavor and shelf life at a fraction of the capital cost of other indoor farms”.

“This indoor farm, and the two others in our system, are critical elements of how Shenandoah Growers is transforming the way perishable produce is grown and distributed,” SGI CEO Timothy Heydon said in a release.

“With the integration of our modular indoor growing technology into our existing national footprint, we can grow amazing certified organic produce that delivers fresh flavor to consumers in a sustainable way, minimizing inputs of water, bio-media, land resources, and food miles.

“We are proud to be a part of transforming agriculture production and distribution for the future.”

SGI’s Rockingham, Virginia farm complex serves as the eastern hub of a nationwide growing system, and with a farming and supply chain platform spanning the country, the group claims its indoor farms cover the Mid-Atlantic, Midwest and South Central market.

The group continues the expansion of its farms, greenhouses and the implementation of an indoor farming hub and spoke system on the West Coast, with completion expected in 2018.

Farming Module Provides Locally Produced Food All Year Round

By Thomas Tapio Press Release 2017-06-22

Farming Module Provides Locally Produced Food All Year Round

A new, unique solution enables profitable ecological cultivation in urban environments

Exsilio, a Finnish enterprise, has developed a high-tech solution for cultivating salad and herbs, among others, in urban environments. The solution comprises a renovated container, where ecological local food can be cultivated efficiently. “Our solution is ideal for example for restaurants and institutional kitchens wanting to produce their own ingredients. The modules also serve as an excellent option for farmers to replace their traditional greenhouses with”, explains Thomas Tapio, CEO of Exsilio.

The 13-metre long farming module, known as EkoFARMER, is a unique market novelty. The unit forms a closed system, which needs only electricity and water to function. This means that the level of humidity, water, and carbon dioxide can be controlled efficiently in order to produce the optimal yield and the best possible flavour. Unlike the majority of other similar systems, EkoFARMER does not use any other nutrients than the ecological cultivation soil developed by Kekkilä.

Exsilio is currently on the lookout for co-operation partners who are interested in developing the farming modules further with the enterprise. In addition to restaurants and farmers, Tapio also envisions various other prospective user groups for the modules.

“EkoFARMER is an excellent option for business fields in need of salads, herbs or medicinal plants, for example. The social aspect of urban farming is also prominent. For this reason, our solution is suitable for associations wanting to earn some extra income, or societies wanting to offer meaningful activities for the unemployed, for example. This is an opportunity to create new micro-enterprises”, says Tapio.

The module can be placed almost anywhere, it does not occupy much space, and it is also transferable.

Making horticulture profitable in urban environments can be challenging, but according to Exsilio’s calculations it is still possible, if the execution is efficient enough. “Our module can produce approximately 55,000 pots of salad per year. The yield will be at least three times the amount produced in a greenhouse, since the cultivated plants are located on multiple floors. Therefore, plants can be cultivated all year round and the cultivation period can be shortened, as the amount of light and humidity can be controlled perfectly.”

The final price of the modules has not yet been determined, but according to Tapio’s calculations, it is likely to be slightly over 100,000 euros. The enterprise has also developed a leasing model, which allows customers to use EkoFARMER with a monthly payment of a few thousand euros.

More information:

Thomas Tapio, CEO, Exsilio, +358 44 9809682

www.ekofarmer.fi

www.exsilio.fi

Vertical farms: "Making Nature Better"

Vertical farms: "Making Nature Better"

PORTAGE, Indiana -- Do not be confused by the drab facade of the warehouse in this Northwest Indiana industrial park. It's a farm... and it could well be the future. They're called "vertical farms" -- The entire operation is indoors, and it's a trend that could turn urban areas into agricultural hotbeds.

Workers at the Green Sense Farms warehouse in Portage, Indiana.

CBS NEWS

You'll find arugula and parsley, basil, kale and other greens that grace our plates.

"We are growing nine varieties of lettuces,'' said Robert Colangelo, the founder of Green Sense Farms.

Or you could call him Mr. Salad.

Bob Colangelo CBS NEWS

"I guess. I'll take that. I could be called worse," says Colangelo.

This is how he does it, with a pink light from a light-emitting diode, or LED

"It gives you a very concentrated amount of light and burns much cooler. And it's much more energy efficient," says Colangelo.

No sun? No problem.

Researchers believe plants respond best to the blue and red colors of the spectrum, so the densely-packed plants are bathed in a pink and purple haze. They're moistened by recycled water; bolstered by nutrients; and anchored in a special mix of ground Sri Lankan coconut husks.

"We take weather out of the equation," says Colangelo. "We can grow year round and we can harvest year-round."

This abundance keeps the prices consistent year-round at local groceries.

Scott Hinkle, a local chef, says the sunless harvest tastes great. Hinkle shows off a "blossom salad" he serves which can include watercress, micro-arugula or kale.

With less water and fertilizer, fewer workers and no gasoline, it's more economical to grow greens this way than on a traditional farm.

Since there are no bugs, there's no need for pesticides. No weeds, so no need for herbicides.

And Colangelo really knows his plants. He says workers play classical music to create happy vibes for the flora.

Is there a composer the plants prefer? If it's Metallica, we don't want to eat it.

As to whether he's cheating nature...

"We're making nature better," says Colangelo.

High-Tech Indoor Farm Nabs $20 Million in New Funding

Bowery, an indoor farming company that deploys a lot of high-tech solutions – including propriety software systems, robotics and monitoring plants via machine learning – announces it has secured a Series A funding round of $20 million from several investors, including General Catalyst, GGV and GV.

High-Tech Indoor Farm Nabs $20 Million in New Funding

JUNE 14, 2017 09:02 AM

Bowery’s crops are planted indoors in vertical rows and meticulously monitored, “capturing a tremendous amount of data along the way,” according to the company’s website.

© Bowery

By Ben Potter

AgWeb.com

Bowery, an indoor farming company that deploys a lot of high-tech solutions – including propriety software systems, robotics and monitoring plants via machine learning – announces it has secured a Series A funding round of $20 million from several investors, including General Catalyst, GGV and GV.

“Shaping the future of food requires re-imagining the food supply chain from seed to store,” according to Spencer Lazar, partner with General Catalyst. “The Bowery team is pioneering technology that will move the entire agriculture industry forward. We are proud to be in their corner.”

Bowery uses hydroponics practices it says uses 95% less water and is more than a hundred times more productive comparable to the same footprint of land of traditional agriculture. The company also calls the leafy greens it grows “post-organic” – that is, pesticide-free and grown in a completely controlled environment.

Perhaps most importantly – the food tastes good, Lazar says.

“Their produce tastes delightful,” he says. “Their farm economics are exciting, and the conscientiousness of their approach is inspiring.”

Bowery’s crops are planted indoors in vertical rows and meticulously monitored, “capturing a tremendous amount of data along the way,” according to the company’s website. “We’re able to remove the age old reliance on ‘eyeballing.’ We can give our crops exactly what they need and nothing more -- from nutrients and water to light.”

The company sells its produce to nearby restaurants and Whole Foods stores in and around New York City.

Bowery’s CEO, Irving Fain, says he’s thrilled by the level of support the company has received so far. In February, the company announced a separate $7.5 million in total venture funding had also been raised.

The vertical farming market has proven a lucrative one in recent years. According to one market research report, the global vertical farming market is expected to grow to $5.8 billion by 2022, with an annual growth rate of nearly 25% between 2016 and 2022.

Scotland's First Vertical Indoor Farm To Be Operational by Autumn

2017 |Arable,Crops and Cereals,News

Scotland's First Vertical Indoor Farm To Be Operational by Autumn

Scotland’s first vertical indoor farm to be operational by Autumn 2017

An indoor vertical farm in Scotland will be completed in the next few months, the company behind the project has said.Intelligent Growth Solutions (IGS), the Dundee-based company, says it will make vertical farming - the process of producing food on vertically stacked layers indoors - commercially viable through reduced power and labour costs.The modern ideas of vertical farming use indoor farming techniques and controlled-environment agriculture (CEA) technology, where all environmental factors can be controlled.These facilities utilise artificial control of light and environmental control, such as humidity, temperature and gases."Vertical farming allows us to provide the exact environmental conditions necessary for optimal plant growth," said Harry Aykroyd, the CEO of IGS."

By adopting the principles of Total Controlled Environment Agriculture (TCEA), a system in which all aspects of the growing environment can be controlled, it is possible to eliminate variations in the growing environment, enabling the grower to produce consistent, high quality crops with minimal wastage, in any location, all year round."'Most advanced technology'Omron, an automation company collaborating in the project, said it uses the most advanced technology to solve humanitarian needs.Their Field Sales Engineer Kassim Okera said: "Omron's unique integrated product offering and Sysmac platform combined with extensive market experience, underpin the most innovative vertical farm in the UK which has the potential to be the first vertical farm in the world that is economically viable."Professor Colin Campbell, Chief Executive of the James Hutton Institute commented: "

We are delighted to see how well the work on IGS' indoors growth facility at our Dundee site is progressing."This initiative combines our world-leading knowledge of plant science at the James Hutton Institute and IGS’ entrepreneurship to develop efficient ways of growing plants on a small footprint with low energy and water input.

"Singapore is also considering a huge vertical farm. The city is planning a 250-acre agricultural district, which will function as a space to work, live, shop, and farm food.

The Opportunities and Challenges of Building a Rural Agtech Startup

Startup activity in the US is typically concentrated on the two coasts, particularly in California, New York, and Massachusetts, and agtech startups are no different. In 2016, agtech startups in those three states raised 73% of all investment dollars during the year. There are, however, several startups cropping up in America’s rural regions, which can make a lot of sense considering where many of their customers will be

The Opportunities and Challenges of Building a Rural Agtech Startup

JUNE 21, 2017 LOUISA BURWOOD-TAYLOR

Startup activity in the US is typically concentrated on the two coasts, particularly in California, New York, and Massachusetts, and agtech startups are no different. In 2016, agtech startups in those three states raised 73% of all investment dollars during the year. There are, however, several startups cropping up in America’s rural regions, which can make a lot of sense considering where many of their customers will be. And there are some leading investors moving away from Silicon Valley to find investments, such as AOL founder Steve Case who’s staking a claim on rural entrepreneurs with a new $525 million fund focused on investing outside of New York and San Francisco.

Lisa Benson from the Farm Bureau introduced me to three rural agtech startup entrepreneurs that took part in the Farm Bureau’s Rural Entrepreneurship Challenge last year: Dan Perpich of Vertical Harvest Hydroponics, which is an indoor agricultural startup based in Anchorage, Alaska; Martin Bremmer from Windcall Manufacturing in Venango, Nebraska, who has developed a miniaturized grain combine called the Grain Goat; and Albert Wilde, from Wild Valley Farms in Croyden, Utah, who is producing sheep wool fertilizer from waste wool.

Applications are now open for the 2018 Challenge with a deadline of June 30, 2017, and the opportunity to win $145,000 worth of prizes. You can find out more and apply here.

In this week’s podcast, I speak to the three rural agtech startup entrepreneurs to find out more about the challenges they face launching agtech products from their respective rural bases.

Here’s an abridged transcription of the podcast.

AgFunderNews

The Opportunities and Challenges of Building a Rural Agtech Startup

Dan Perpich: I am the founder of Vertical Harvest, and we are based in Anchorage, Alaska. We started two and a half years ago, and we started designing and producing and marketing commercial hydroponic systems installed in 40-foot shipping containers, and the reason we did that is because food prices in Alaska and Canada and the North, the Arctic, are out of control. And we thought there was an opportunity to give people the means to farm locally and produce their own food locally and that would be a good market and a valuable product to people. And here we are two and a half years later, and we’re just happy to still be here.

Albert Wilde: I live in Croydon, Utah, and the company that I’ve started is called Wild Valley Farms. We do all sorts of compost, soils, landscaping materials and that, but the product we’ve developed is a natural organic fertilizer that will fertilize for a whole season, and it’ll retain water, reducing the amount of watering by about 25%, and it’s made from waste wool from sheep.

I’m a sheep rancher, and we have 2,800 sheep and 300 head of cows, which is why we started with doing the compost to be able to manage animal waste and make a value-added product for consumers for their gardening and what not. And then when we found that wool was so high in nitrogen that we started working towards trying to make the wool a useable product for an end consumer. So we pelletized it, and we’ve been selling the wool pellets to nurseries and greenhouses and for commercial use. They take the wool pellets and mix it in with their hanging baskets or potted plants that they’re selling to consumers. And then we also bag up the wool pellets and sell directly to consumers and through distribution channels.

Martin Bremmer: I’m in Southwestern Nebraska, and our company’s called Windcall Manufacturing and our first product is called the Grain Goat. It’s essentially a grain combine that’s handheld because it’s very tiny. The purpose of this combine is so that you can sample small amounts of grain, small varieties, rapidly, and then use the onboard moisture meter to tell you what the moisture content of the grain is, enabling you to determine whether or not that field that you just sampled is ready to harvest.

LBT: Thinking about all the startup activity that’s taking place in agtech in San Francisco and New York that you’re all aware of, how do you think building a startup in a rural region compares?

Bremmer: That’s a tough question, but what I’m familiar with in terms of raising raising capital is that there’s always more zeroes attached to the project [on the coasts]. And so there’s different [investor] groups that seem to be targeted by the startups, and the VC groups are pretty well established and have great reputations. They do some incredible due diligence, and when I think about my own personal experience, when we’re doing fundraising for Wind Call Manufacturing, it’s scaled back quite a little bit.

The same process goes on it’s just scaled back in the scope of expectations, which is a huge advantage for us because early stage funding is a little more easily accomplished because there’s more understanding of the dynamic with small companies like ours: our investors understand that the zeroes are going to be smaller, the growth is going to be slower, and they don’t have these rapid slingshot unicorn dreams of what’s going to happen with your company, they get that this is, I don’t want to call it a niche market, but it’s an ag market, so it’s not a mainstream US market. And so I’m not having to redirect their focus and expectations, they already understand that.

Wilde: Most ag startups are building more of a legacy business. They’re focusing on, “I’m gonna build something that helps with the industry that I know and love, and I’m gonna keep this,” more. Whereas a lot of I think the tech side of things, people get into it and there’s not a homegrown part of it. So I guess it’s just, I came up with this technology, and I’m putting it out there, and I don’t care who buys it or how fast and it can go. It can go away from me.

And I think from what I’ve seen with a lot of ag startups is they feel more like they’re building this because they saw a need for something that they love and they want to grow and keep it that way.

And so with different investors, they have to know what your end goal is before they invest in you, and as Martin said, the expectation with a legacy company is much, much lower. The profit, returns… because you’re not looking to come up with an idea and just sell it. You’re looking to come up with an idea and build it.

LBT: Are your investor bases generally local investors, or have you attracted investment from across the country or even the globe?

Wilde: We have a huge potential for growth, and we have some very large companies that are looking to license our product that’ll put it out to a wide distribution for consumers, but all of the investment came from myself or family or partners. And the reason is, I’ve got two partners that have put in $2 million worth of assets, and then for myself I’ve got a ranch and farm, so I’ve received an ag loan from this lender at a 3.8% interest, which I mean is really cheap, but that’s because I have some ag assets that they’re willing to loan that sort of money on. Most investors like a venture capitalist, you tell them that you’ve got funding at 3.8% or 5% or whatever, they know that you’re not interested.

LBT: Dan, how have you funded Vertical Harvest?

Perpich: We’re self-funded, so we put our own money in to start our company, and as we’ve started growing revenue we’ve been able to reinvest and continue development. We’ve been very lucky in that regard. Going back to your first question Louisa, it’s important to remember that farmers are by definition entrepreneurs; a farmer owns and operates his own business, and they may start by getting family loans or owner-funded farms by younger farmers, but I think it’s quite important to remember that. Up here in Alaska, I’d say we’re probably one of the more rural places in the US — some would argue quite remote — and I think it does complicate fundraising a little bit, but there’s still money in the system and I think we’ve got a lot of benefits from the connectivity of today’s world. I may not be able to go down to the row of offices if I’m fundraising but we’ve got email, we’ve got Skype, we’ve got conference calls. I think that stuff has value to us and also has value to our customers.

LBT: If you were to seek external capital where do you think you’d go first? Would you look for local Alaskan investors as the first point of call?

Perpich: My thoughts are that we need to get a strategic benefit out of any investment that we take. If we want just money, we can go to a lot of different places just for money, but we look at what our goals are that we’re trying to accomplish; operationally how do they fit in, can they connect with customers, can they lead a round and bring people to the table?

Just to frame it, we’re in the process of putting together what we’re calling a Series A to grow our workforce, so all those questions are really near to us right now. When we talk to investors we ask them, are you going to bring us sales people, are you gonna bring us customers, are you going to bring us other investors?

I think it’s important that we don’t just go and take the first guy that’s got money because from my experience the geography isn’t just limited to the West Coast, the geography is North America, the world. And there are quite a few people out there, and so if we just go to the guy down the street and he connects me to more people in Alaska, what value does that bring to me?

Bremmer: I’ve got a question for you Dan, just because where you live you could attract Canadian investors just as easily as US investors, so does that throw an added layer of complexity if you pulled in some Canadian interest?

Perpich: You know it does, but that’s all a solvable problem. If a guy from Canada wants to invest in my business, there are some questions such as are we gonna open an office there? Are we gonna do the investment in Canadian dollars or US dollars? You know, he’d have to answer some questions about mitigating currency risk because the Canadian dollar goes up and down against the US dollar. So there are questions but I think those are all solvable problems and quite frankly, if you know a guy who’s Canadian and wants to invest in me, I mean, you want to shoot us an email and connect us? [laughs]

Bremmer: I’ll send him your way. [laughs]

LBT: So, what would you say have been the main challenges that you’ve faced in launching your businesses and getting them to where they are today? And, what do you foresee as being the challenges going forward, if those challenges shift and change?

Wilde: So I think the most difficult part of being an ag startup is actually developing the product itself. I mean, I think each of us has a product that has to be manufactured, a physical thing that you’re actually building, and for myself, like I said my partners had invested $2 million, which is all in the equipment to be able to produce the product that I have. That’s a little different than, like, other tech things, startups, where it’s more of a technology and not just a physical product itself.

And so trying to get people to believe in you, or to believe in your product or even to know why it’s better or why it’s going to help before you have a real prototype, makes it very challenging that way. And I think that’s probably one of the most challenging for an early, early stage ag startup. Then, once you get your prototype and you start to build those prototypes, it’s being able to put it into more of a mass production and then like Dan mentioned, the salesforce; trying to get a salesforce out there to be able to sell your product so you can take in the materials you need to build you product but also have someone out there selling it so that your inventory doesn’t eat you alive.

LBT: What would you say are the benefits to you being based in Croydon, Utah? Are you near your customer base, or is it near the source of your product?

Wilde: I don’t know if there’s all that much advantage to it, [except] being connected through agriculture. As a sheep producer, I’ve been invited to a number of the different wool grower conventions around the country to inform them, the other sheep producers, about my product and what I’m doing in actually buying waste wool from them and entering a value added product. And that’s a huge benefit over anyone else [that might produce this product], the greenhouses or whatever, they’re like, “Oh, we really like this product, maybe we could do it,” and I’m like, well, okay, but for them they’re gonna have to go to a wool warehouse where the cost is going to be much more expensive, and I can go directly to buy the materials. So that’s a huge advantage just being in ag in that way.

Bremmer: There are two main challenges that jump into my forethoughts. One is because we’re a new product with a new market, we really have to push hard and shovel a lot of coal into the fire for what we call educational outreach – most folks would just call it flat-out marketing – we need to get our product in the mind of all our potential customers just because we don’t have competing products, and so we’ve spent a lot of our time educating farmers as to the advantage and the asset of purchasing our product to make their world a little bit easier and make some savings actually happen on their balance sheet. And so the huge challenge there is just because of the time, the energy, and the dollars it takes to execute that effort.

And then our number two challenge is keeping our cost of goods down. Because we’re manufacturing a mechanical device, the cost of goods can always come down a little bit. And it’s nice where we live; we’re in Nebraska so we can take advantage of the multitude of manufacturers in Nebraska, Kansas, and Colorado, where we can actually make them compete against each other to keep our cost of goods down when we’re subbing out a lot of parts. So that’s a huge asset to us because we live in a low cost of living part of the US and so the manufacturers in a 500-mile circle from our home base actually turn out quality products for much, much less than if we were on either coast and using the same skill set manufacturers. So huge advantage there but still driving that cost of goods down in a big deal for us; being a startup, we cannot make purchases in volumes that would really make a difference, not yet at least. And so as soon as we drive some sales further and faster, then maybe we can take advantage of that.

LBT: To go back to your first point Martin — the bit about the adoption rate — this is something that I think a lot of investors look at as being particularly challenging in agriculture, because with a lot of products you’ve only got one growing season a year, so one time for the farmers to test the product or even for you to iterate on the development of your product.

I’m also wondering how much behavioral change is required for them to adopt your technology and use that in the field, before harvest. What is your sense on that and how quickly that could happen?

Bremmer: Behavioral change is paramount for what we’re trying to sell, because we’re actually asking grain farmers to change their harvesting habits and I have to kind of draw out farmers in general, but especially grain farmers because that’s who I’m familiar with; that’s an unusual market on a good day.

Because we’ve got a group of smart people, sometimes they’re highly educated, sometimes they’re not, but they’re very traditional, and they’re very family-based businesses, and so we have lot of customers who run multi-million dollar family corporations with very little marketing education and business marketing education or just overall most farmers aren’t MBAs. And they like it that way, so they do everything by the gut, or they do everything traditionally. And so it’s a bit of a bullish kind of audience, where we have to show up at the trade show and get these folks to open their minds a bit and say, “You need to change a habit that you’ve had for the last 30 years, to improve your balance sheet.” And I can watch their eyes glaze over for a minute, and then once I get past that, they start thinking a little bit and then their business mind, their common-sense mind, kicks in, and then I have them because they start to realize oh, there is a change.

But it’s funny how you can split that demographic down into age, because anybody 55 and older, they’re pretty resistant to it. But between 30-55, they’re open to it, and they think about it, but younger than that they haven’t really had enough experience on the family farm to really understand the impact of a tool like what we are selling.

LBT: What is it that suddenly gets through to them? Are you throwing figures at them and saying that you’ll actually help them increase their revenues by x percent, or whatever?

Bremmer: The way I crack through that force field that they’ve got is by using their Achilles heel. The one thing that you can appeal to a farmer with is, what are their expenses, and is there a way that you can minimize their expense?. So that’s our biggest asset from a marketing point of view; we’re able to get the farmer to actually recount to us a story where they wasted a lot of time or a lot of money on a particular season, and by using our tool they would have eliminated that entire scenario, and that’s what gets me in the front door of their mind so that they can realize, oh my gosh yeah, maybe this is kind of an arcane method that we’ve been doing for years. Maybe there’s a new tool like the Grain Goat that avoids that risk. And so now we’ve got the cost savings that makes them go okay, I can see the value of this.

LBT: Dan, tell me about your challenges in getting Vertical Harvest Hydroponics set up?

Perpich: Oh, man, Louisa, I don’t even know where to start on that question [laughs]. You know I’ve got to say I figure if you google, “Basic entrepreneur mistakes,” we’ll probably put a checkmark next to just about every single one of them.

There a lot of pitfalls that you can just jump into, a lot of black holes and time wasting. I think our biggest challenge is that our product is sort of in a lot of ways a new paradigm shift. A lot of people are used to the idea of food being grown outside of Alaska, far away, and so to have technology that can do it at places where – I mean we’ve got the first hydroponic farm above the Arctic Circle, and it was growing food successfully for the market at 50 below zero this year. Kudos to our customers for being the first people to bring the technology out there because it’s a risky and daunting task. And I think the challenges show the customers that not only is it possible, it’s not only something you read about in a science publication or a science magazine, but it’s actually real and you can do it.

The challenge I guess is showing people to the point where they don’t just see it and think, “Wow that’s a cool thing,” but to the point where they see it, and they say, “That’s a cool thing, and I want it, and I want to do that, and that’s how I want to support my family.”

It’s definitely one of our challenges for sure. And going back to what I think Martin had mentioned about when you hit a certain age demographic, a lot of the farmers are maybe not as interested. We’ve definitely seen that as well, sort of the older farmers that we’ve dealt with, the guys in their 50s and 60s, their sort of note is, “That’s very cool, and I think it is the future, but at my age, I’m not up for an adventure.” And so we’ve definitely seen most interest from the younger farmers, the next generation of farmers. And if there was anything that I could make a very brash pitch about, I’d say what would be helpful for those guys is if they had access to cheaper money, because what we’ve seen with our technologies is that they’re very new, and the low-risk institutions like banks, traditional financing sources, don’t want to finance them yet, so they’re left with more expensive sources of money. And that’s gonna change, we hope, but we’d like it to change faster of course.

LBT: So who are your main customers?

Perpich: Right now they’re either current farmers and people that want to be farmers. And a lot of what we’ve found in Alaska anyway is the people that want to be farmers are corporations that have employees in these communities and want to grow their revenue streams, or they have a local interest in the community, and they’re willing to take the risk because of the benefits to the communities. Definitely, people are on the lower edge of the age demographic; I’d say 20s-40s in that range.

LBT: And is the fact that how you’re growing the produce indoors, organically, or non-GMO or pesticide free, etc: is that a big draw do you think for some of the farmers? To be able to get some of those price premiums?

Perpich: You know, it’s very attractive to farmers in the lower 48 – just as a side note lower 48 is what we call all of you guys. But what you’ve gotta understand is that a lot of these guys, they’re seeing just lettuce, for example, that’s three weeks old, it’s four weeks old, it’s well on its way to spoilage, and it gets sold in these communities, and it’s all they have. I mean they don’t have anything else.

So, for them, they like the idea that it’s organic or that it’s non-GMO or that it’s hydroponic, but they really care that it’s fresh and that they know the farmer personally. I mean these are communities of a couple of thousand people, and it’s not uncommon for them to knock on the door and ask for a tour and normally the farmer will give them a tour because he’s known them for 20 years.

I’d say that’s more of the big selling point for the customers in Alaska anyway.

LBT: How many of your containers are out there now?

Perpich: We’ve sold six, so, we’re young. We’re early stage.

Listen to the rest of the podcast to find out what these entrepreneurs’ goals are over the next few years, and for more insights from the conversation.

Indoor Farming Start-Up Plenty Secures $200m In Funding

Indoor Farming Start-Up Plenty Secures $200m In Funding

Posted By: News Deskon: July 19, 2017In: Agriculture, Environment, Food, Industries, Uncategorized

US indoor farming start-up Plenty has obtained $200 million in funding led by the SoftBank Vision Fund as it expands its agriculture model.

Plenty claims to be developing patented technologies to build a ‘new kind of indoor farm’ that uses LED lighting and micro sensor technology to deliver higher quality produce.

The company said the investment will boost its global farm network and support its mission of ‘making fresh produce available and affordable for people everywhere’.

As part of the deal, SoftBank Vision Fund’s managing director Jeffrey Housenbold will join the Plenty board of directors.

SoftBank Group Corp chairman Masayoshi Son said: “By combining technology with optimal agriculture methods, Plenty is working to make ultra-fresh, nutrient-rich food accessible to everyone in an always-local way that minimises wastage from transport.

“We believe that Plenty’s team will remake the current food system to improve people’s quality of life.”

Based in San Francisco, Plenty plans to build its farms near the world’s major population centres to produce GMO and pesticide-free produce while minimising water use.

Plenty CEO and founder Matt Barnard said: “Fruits and vegetables grown conventionally spend days, weeks, and thousands of miles on freeways and in storage, keeping us all from what we crave and deserve — food as irresistible and nutritious as what we used to eat out of our grandparents’ gardens.

“The world is out of land in the places it’s most economical to grow these crops.”

He concluded: “We’re now ready to build out our farm network and serve communities around the globe.

BIG Envisions Multi-Purpose Biomass Power Plant in Sweden

BIG Envisions Multi-Purpose Biomass Power Plant in Sweden

As you find yourself filled with curiosity, peering through the windows of a geodesic dome, its aesthetic value goes unchallenged. However, its level of functionality in relation to indoor agriculture remains questionable. Amidst the uncertainty on the validity of such structures, Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) envisioned their scheme for a “biomass cogeneration plant” within a geodesic dome for the city of Uppsala, Sweden. During the colder months, the power plant will employ technologies with the potential to generate energy by converting biomass waste into heat, electricity, and biofuels through combustion or other conversion methods. It will serve to entertain in the summertime.

The transparency of the enclosure is an inviting aspect of the power plant that is typically nonexistent in this kind of facility - it communicates a rare level of public education and community engagement for this typology. Although still in the idea phase, it’s an exciting vision of how future energy production might look.

The city of Uppsala invited BIG to design a biomass cogeneration plant that would offset its peak energy loads throughout the fall, winter and spring as part of an international competition (ultimately won by Liljewall Arkitekter). Home to Scandinavia’s oldest university and landmark Uppsala cathedral, the plant proposal’s biggest challenge was to respect the city’s historic skyline.

Considering the project’s proposed seasonal use, BIG envisioned a dual-use power plant that transcends the public perception; in the summer months, the “crystalline” proposal was designed to transform into a venue for festivals during the peak of tourism.

“By harnessing the economies of scale associated with greenhouse structures it is possible to provide a 100% transparent enclosure to provide the future massive silhouette on Uppsala’s skyline with an unprecedented lightness while allowing the citizens to enjoy educational glimpses of what happens within. Rather than the conventional, alienating hermetic envelope of traditional power plants, the crystalline volume serves as an invitation for exploration and education. The next generation of creative energy.”

“BIG’s design proposal fuses two conventional industrial archetypes into an unconventional hybrid: the plant and the greenhouse. Both have been developed to provide a rational and efficient form of enclosure to massive industrial facilities: for manufacturing and agriculture respectively,” stated the practice in a press release.

CONTENT SOURCE FROM HERE ARCHDAILY

Tagged: #greenhouse #dome #geodesic dome #biomass #power plant #bjarkeinglesgroup #sweden #cogeneration #venue #festivals #energy production #sustainability #hybrid #architecture #bjarke ingels

Urban Aquaponic Farmer and Chef Redefines Local Food in Orange County, CA

Urban Aquaponic Farmer and Chef Redefines Local Food in Orange County, CA

Heads of lettuce gain their sustenance through aquaponics channels at Future Foods Farms in Brea. Photo courtesy Barbie Wheatley/Future Foods Farms.

In a county named for its former abundance of orange groves, chef and farmer Adam Navidi is on the forefront of redefining local food and agriculture through his restaurant, farm, and catering business.

Navidi is executive chef of Oceans & Earth restaurant in Yorba Linda, runs Chef Adam Navidi Catering and operates Future Foods Farms in Brea, an organic aquaponic farm that comprises 25 acres and several greenhouses.

Navidi’s road to farming was shaped by one of his mentors, the late legendary chef Jean-Louis Palladin.

“Palladin said chefs would be known for their relationships with farmers,” Navidi says.

He still remembers his teacher’s words, and now as a farmer himself, supplies produce and other ingredients to a variety of clients as well as his restaurant and catering company.

Navidi’s journey toward aquaponics began when he was at the pinnacle of his catering business, serving multi-course meals to discerning diners in Orange County. Their high standards for food matched his own.

“My clients wanted the best produce they could get,” he says. “They didn’t want lettuce that came in a box.”

So after experimenting with growing lettuce in his backyard, he ventured into hydroponics. Later, he learned of aquaponics. Now, aquaponics is one of the primary ways Navidi grows food. As part of this system he raises Tilapia, which is served at his restaurant and by his catering enterprise.

Just like aquaponics helps farmers in cold-weather climes grow their produce year-round, the reverse is true for growers in arid, hot and drought-prone southern California.

“Nobody grows lettuce in the summer when it’s 110 degrees,” Navidi says.

But thanks to aquaponics, Navidi does.

Navidi also puts other growing methods to use at Future Foods Farms. He grows San Marzano tomatoes in a greenhouse bed containing volcanic rock (this premier variety was first grown in volcanic soil near Mount Vesuvius in Italy). Additionally, he utilizes vertical growing methods.

For Navidi, nutrient density is paramount—to this end, he takes a scientific approach in measuring the nutrition content of his produce. In the past, he and his staff used a refractometer, but now rely on a more precise tool—a Raman spectrometer. This instrument uses a laser that interacts with molecules, identifying nutritional value on a molecular level.

With a Raman spectrometer, Navidi measured the sugar content of three tomatoes—one from a grocery store, one from a high-end market, and one that he grew aquaponically. Respectively, measurements read 2.5, 4.0 and 8.5.

Navidi wants his customers to know about these nutritional differences, so he educates his Oceans & Earth diners through its menu and website. Future Foods Farms also offers internship opportunities to students from California State University, Fullerton. Interns conduct research and learn about cutting-edge ways to grow food.

Navidi believes aquaponics and other innovative growing methods can lead to a more robust local food system in Orange County. But he also sees some of southern California’s undervalued resources—namely, common weeds such as dandelion and wild mustard—helping the region become a major local foods player.

“We need more research on nutrients in weeds,” he says. “Dandelions and mustard are power weeds, and need little water.”

While these wild plants are important, they’re no substitute for policy. Navidi would like to see farmers in the county pay lower rates for water, and believes that a revised zoning code is needed for a county that is urban and becoming more so.

“Now, urban farming is happening all over,” he says. “We need changes to our zoning laws—politicians realize that.”

New zoning rules could help others in Orange County venture into aquaponics, something Navidi feels is necessary not only for the county, but for the country.

“For America to be sustainable, it needs aquaponics,” he says.

Ultimately, Navidi’s goal is to provide the best product possible, with an eye toward simplicity, health and wholesomeness.

“Any fine-dining chef is concerned with the quality of their product,” he says. “There’s nothing better than real food. I try to grow the most nutrient-dense tomato possible. Just add sea salt and black pepper—that’s all you need.”

Some Urban Farmers Are Going Vertical

In a factory parking lot in Brooklyn, a crowd of about 100 people gasped and murmured as Tobias Peggs cracked open the heavy metal doors of a white shipping container, allowing pink light to spill out from within.

Some Urban Farmers Are Going Vertical

2017