Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Minnesota Looks To Expand Local Food Opportunities

Minnesota Looks To Expand Local Food Opportunities

From community gardening to developing more food distribution outlets, people in both urban and rural areas of Minnesota are expanding their involvement in the local food movement.

Minneapolis with the adjoining city of St. Paul form the Twin Cities, which is the 14th-largest metropolitan area in the United States. The cities’ metropolitan area has nearly 4 million residents.

Photo courtesy of Karl Hakanson, University of Minnesota Extension

Karl Hakanson, University of Minnesota Extension Educator for Hennepin County, of which Minneapolis is the county seat, said he has had to broaden his definition of agriculture since taking his current position in February 2014.

“Most of my career has been in conventional ag—regular farming,” Hakanson said. “I’ve had to broaden my definition to focus on food. I have been involved lately with the whole issue of food equity and the access to healthy, real food. That also involves having access to land. If people want to have community gardens or develop urban farming, just like people in rural areas, they have to have access to land, which is a big deal.”

Hakanson said the land for urban farming is expensive and hard to obtain and sometimes it’s not available even if people can afford to purchase it.

“Minneapolis has a launched a Homegrown Minneapolis website where interested parties can find available lots to lease for urban farming,” he said. “The problem is the lots may be available for a year or two. This can make it hard to have any kind of permanence. But it is getting better for people who are trying to find vacant lots to do urban gardening.”

Assisting With Urban AG Issues

Hakanson said within Minneapolis more people have gotten involved with community gardening which enables them to grow more of their own food.

“Some of these people may have gotten better at growing their own food that they consider marketing some of it,” he said. “The Homegrown Minneapolis Food Council began operating in 2012 as a resource for all of the activities involved with urban agriculture. The council deals with issues, statutes and regulations related to the city. It also offers various resources for businesses including starting a local food business and business financing. Council members include some urban farming businesses that are trying to succeed commercially including some CSAs (community-supported agriculture).”

Hakanson said the council is a good resource for all kinds of urban farming activities.

“The council was instrumental in allowing urban gardeners to tap into fire hydrants so water for gardening could be metered like it is for regular household usage,” he said. “The council also worked to have the regulations changed regarding people being able to sell their produce from leased city lots and to put up signs to advertise available produce. A recent change is that signs can now be up for 75 days.”

Finding Business Opportunities

Greg Schweser is associate director of local foods and sustainable agriculture for the Regional Sustainable Development Partnerships, a program that is part of the University of Minnesota Extension. Located in St. Paul, Schweser said the program he is involved with works with groups outside of the seven-county metro area.

Greg Schweser, associate director of local foods and sustainable agriculture for the Regional Sustainable Development Partnerships, said the program he is involved with works in the areas of sustainable agriculture and local foods, clean energy, natural resources and tourism.

Photo courtesy of Karl Hakanson, University of Minnesota Extension

“We bring university resources to community groups, organizations and individuals who have great research ideas in sustainable development,” Schweser said. “We work in the areas of sustainable agriculture and local foods, clean energy, natural resources and tourism. An example of what we do is there may be a group of people who want to do a field trial with hoop houses to see what vegetables varieties grow best. They’ll apply to get a research grant through The Regional Partnerships and we will be able to assist them with a faculty horticulturist, students and extension personnel to get those research projects up and going. A lot of the work that I do involves obtaining grants and doing grant projects focused on local food and agricultural issues.”

Schweser said about 30-40 percent of the RSDP projects are food-related. Other projects are related to natural resources, clean energy and tourism.

“A lot of small scale growers work with our group,” he said. “The farther these growers are from the metro area the less likely they are to sell into that market. Unless growers have a large scale production system, it’s not going to be easy for them to market in the metro area. For that market, growers need to have a method of transportation and storage. There are some growers who specialize in one of two things and sell directly into the metro market.”

Many of the growers Schweser works with are producing and selling in their local communities. He said more than 50 percent of small specialty crop growers are women.

“Each of the rural producers has to have a variety of different marketing streams,” he said. “Most of them do, including CSAs, farmers markets, direct-to-wholesale to a local grocery store or food co-op or school food programs. These growers don’t want to be in a situation where a farmers market closes down and that is their only customer.”

Solving Marketing Challenges

Schweser said most rural growers have their own individual marketing plan.

“There are very few systems where growers can produce a crop and not have to worry about how to sell it once it’s ready to harvest,” he said. “They have to find a place for it and that can be work. That is one of the things that a lot of producers are worried about. How to sell their products for a price that they can stay in business. Once that is figured out more people will be able to get into this local food movement.”

Photo courtesy of Greg Schweser

Schweser said RSDP has been involved with several marketing projects.

“One project in Brainerd, Minn., enabled a farmer to set up a food hub that helps around 100 farmers market locally in area counties,” he said. “RSDP has done a number of farmers markets projects helping people set up their markets and determining what is the best type of products to offer, how to display the products and how much to sell their products for to make a profit. RSDP has also worked with the Minnesota Department of Agriculture to develop local marketing labels.”

Schweser said RSDP is currently working with a group at Kansas State University on a project involving rural grocery stores.

“We are looking at how to deliver local foods into rural grocery stores in Minnesota,” he said. “We are trying to identify ways to handle the produce in a way that will make it last longer and look better. And then determine how to get more consumers into the stores to buy this kind of produce.”

For more: Karl Hakanson, University of Minnesota Extension, Hennepin County Environmental Services, (612) 596-1175; khakanso@umn.edu. Greg Schweser, University of Minnesota Extension, Regional Sustainable Development Partnerships, (612) 625-9706; schwe233@umn.edu.

David Kuack is a freelance technical writer in Fort Worth, Texas; dkuack@gmail.com.

40-foot Shipping Container Farm Can Grow 5 Acres of Food With 97% Less Water

The 40-foot containers house hydroponic farms that only draw on five to 20 gallons of water each day to grow produce like lettuce, strawberries, or kale.

40-foot Shipping Container Farm Can Grow 5 Acres of Food With 97% Less Water

by Lacy Cooke

Communities that have to ship in fresh food from far away could start getting local produce right from their parking lots or warehouses thanks to Local Roots‘ shipping container farms. The 40-foot containers house hydroponic farms that only draw on five to 20 gallons of water each day to grow produce like lettuce, strawberries, or kale. Popping up all around the United States, these scalable farms “grow far more produce than any other indoor farming solution on the market” according to co-founder Dan Kuenzi. Local Roots is even talking with SpaceX about using their farms in space.

Local Roots’ 40-foot shipping container farms, called TerraFarms, grow produce twice as fast as a traditional farm, all while using 97 percent less water and zero pesticides or herbicides. They can grow as much food as could be grown on three to five acres. They’re able to do this thanks to LED lights tuned to specific wavelengths and intensities, and sensor systems monitoring water, nutrient, and atmospheric conditions.

Related: Pop-up shipping container farm puts a full acre of lettuce in your backyard

The process from setup to first harvest takes only around four weeks. TerraFarms can be stacked and connected to the local grid. CEO Eric Ellestad said in a video 30 million Americans live in food deserts, and their farms could be placed right in communities that most need the food.

Los Angeles is already home to a farm with several shipping containers, and a similar one will be coming to Maryland this year. It could offer local food like strawberries in January.

And Local Roots’ technology could one day allow astronauts to consume fresh produce in space. Their growing systems could offer a food source on long-term, deep space missions. Ellestad told The Washington Post, “The opportunities are global and intergalactic at the same time.”

Local Urban Farmer Educates Community On How To Grow Produce Without Breaking The Bank

File photo. (Ben Smith/The Daily Iowan)

Jun 26, 2017 DI Editor

Local Urban Farmer Educates Community On How To Grow Produce Without Breaking The Bank

Iowa City community members learn about the business of urban farming.

By Autumn Diesburg | autumn-diesburg@uiowa.edu

With urban farming continuing to take hold in communities, would-be urban farmers are considering the logistics of owning and profiting from what seems to some to be an unorthodox business.

At a Practical Farmers of Iowa Field Day on June 24, members of the Iowa City community gathered to learn more about the business of urban farming. Hosted by urban farmer Jon Yagla and the Women Food and Agriculture Network program coordinator Wren Almitra, the program discussed the various facets of urban farming, including Yagla’s business plan and financing.

“Sometimes, it makes sense to grow greens and sell to restaurants,” Yagla said. “The [community-supported agriculture] worked for me.”

Yagla said his business plan relied on growing food as an extension of homesteading for community-supported agriculture, which Almitra said is a “member-based farm business.”

Members purchase either a full share for $750 or a half share for $375 in a farm, Yagla said. The program has a 30-week season lasting from the first week of May to the last week of November. Most members pay an upfront deposit in late winter or early spring, usually beginning in February or March. This allows farmers to pay for seeds and equipment in a time when, otherwise, they are producing no income, Yagla said. In return, full-share members receive a box of produce every week, and half-share members receive a box every other week.

Currently, Yagla said he has 30 members in his group, which is mostly a word-of-mouth endeavor. Potential members contact Yagla or other local community-agriculture groups, though the group does have social-media and Internet sites for outreach and promotion.

RELATED: ‘New age’ farmers grow local produce year-round

Yagla said in regards to financial planning, he recommends keeping both living and business expenses low, knowing and being a part of available markets, and having some experience with farming or homesteading. He also recommends scaling the size of community agriculture to the size of the budget.

Careful financial planning is key for Yagla, who said his only source of income is what he earns from his urban farm. In 2016, he grossed $15,000 with a net of $12,000.

“The [community-agriculture] size was based on what I thought my living expenses and my needs are and how much land I could manage,” he said. “I’m about as frugal as I can be.”

For those such as Debra Boekholder, a Practical Farmers of Iowa member and events assistant, the gains of urban farming are a good local food source.

“It is a solution to struggles with access to healthy foods,” she said. “You can grow food in town and provide it to your neighbors. You don’t have to go miles and miles.”

Still, others such as Abbie Shain, a graduate student in social work in St. Paul, Minnesota, have yet to be persuaded on the practicality of urban farms. Shain said after working on urban farms in St. Paul and Minneapolis, she would not consider starting one.

“It was not successful,” she said. “It was successful at growing vegetables but not sustaining farmers.”

Yagla, however, said owning an urban farm is profitable and a worthwhile community cause.

“The gain is that it’s meaningful work that reduces exploitation,” he said. “It’s a way for people to get food locally and honestly. I want to produce [a] local economy where goods are produced and shared among neighbors and friends.”

Please support award-winning college journalism and engagement. Click here to donate.

7 Ways Chicago Is Becoming the New Beacon of The Sustainable Food Movement

Chicago is undergoing a foodie revolution. From passing the nation’s largest soda tax to exploring new and intriguing options for local food, the Windy City is making leaps and bounds to become a beacon of sustainability.

7 Ways Chicago Is Becoming The New Beacon of The Sustainable Food Movement

JULY 5, 2017 by EMILY MONACO

Chicago is undergoing a foodie revolution. From passing the nation’s largest soda tax to exploring new and intriguing options for local food, the Windy City is making leaps and bounds to become a beacon of sustainability.

Don’t believe us? Here are seven fantastic initiatives the Windy City has undertaken to further the transition to great, sustainable food.

1. MightyVine Restores Damaged Farmland with Tomatoes

Just west of Chicago in the prairie town of Rochelle, IL, indoor tomato grower MightyVine has restored acres of farmland that had been damaged by a developer. The growers use Dutch technology comprising a special diffused glass and radiated heat to grow tomatoes 365 days a year. The super-local tomatoes are delivered to stores just a few hours away in Chicago as soon as they’ve been picked.

Sustainability is particularly important to MightyVine farmers, who have managed to provide a 90 percent water savings over field-grown tomatoes, not to mention reduced pesticide use as compared to most conventional growers.

2. Homestead on the Roof Gets Its Organic Produce Ultra-Locally

You can’t get more local than the organic produce grown on the 3,500-square-foot organic rooftop garden at Homestead on the Roof. Executive Chef Scott Shulman has his pick of herbs, chilies, tomatoes, peas, and more to concoct his versatile, seasonal menu, which is served on the 85-seat patio that sits right next to the rooftop garden, which also features two vertical hanging gardens, and dozens of planter boxes.

3. Daisies Keeps Local Produce in the Family

When Daisies opened last month, Chef Joe Frillman realized his dream of combining his passion for handmade pasta and locally sourced crops, almost all of which come from Frillman’s brother’s farm in nearby Prairie View, IL. But Frillman is taking the old trope of locally sourced ingredients to the next level, with the goal of rolling out an in-house fermentation program, too.

Daisies is also making strides in recycling cooking oil: used cooking oil is donated to be recycled for biodiesel, and the resulting profits are donated to charity.

4. Slow Food Chicago Highlights the Importance of Community Gardening

Member-supported non-profit Slow Food Chicago is one of the largest chapters of Slow Food USA, with more than 500 members. Its myriad projects include the preSERVE Garden, a project created in 2010 in cooperation with the North Lawndale Greening Committee, the Chicago Honey Co-Op, and NeighborSpace.

In 2013, the city lot harvested more than 430 pounds of food from 31 different crops, and the garden continues to grow today.

5. The Urban Canopy Attacks the Problem of Nutrition in Schools on the Local Level

Founded in 2011, the Urban Canopy comprises an indoor growing space and a two-acre community farm in the Englewood neighborhood of Chicago. But more than mere growers, the Canopy members see themselves as “educators and advocates for the urban food movement.”

Founder Alex Poltorak’s vision began while working with Chicago Public Schools as an Education Pioneer Fellow. After exploring how nutrition affects children in school, he was inspired to create the project to utilize idle urban spaces to attack this problem at the community level. Through volunteer availabilities, a Compost Club, and a CSA, the group endeavors to “make farming as easy as possible on as many unused spaces as possible.”

6. Chicago O’Hare Brings Gardening to the Gate

An unused mezzanine space of Chicago O’Hare Airport’s G terminal has been transformed into the world’s first “aeroponic” garden by Future Growing LLC. The garden, made up of a series of vertical PVC towers where herbs, greens, and tomatoes are grown, uses a mere five percent of the water normally used for farming.

The produce grown in the airport is used by local chefs, including Wolfgang Puck, who runs a restaurant in the airport.

7. Marty Travis Transforms Nutrient-Sapped Soil into Sustainable Farmland

Marty Travis is a seventh-generation Illinois farmer. As his farming community fell victim to Big Ag, Travis decided to do something about it. He created Spence Farm, a 160-acre beacon of biodiversity where he grows a variety of ancient grains and heirloom fruits and vegetables and raises heritage breed livestock, nearly all of which is sold locally to chefs in Chicago. His story of preserving the history and practice of small sustainable family farming in is told in the film Sustainable Food.

This Food Forest On A Barge In New York Floats The Idea of Fresh Food for Cities

This Food Forest On A Barge In New York Floats The Idea of Fresh Food for Cities

Swale brings free foraging to the concrete jungle

by Alessandra Potenza@ale_potenza Jul 12, 2017, 8:00am EDT

Photography by Amelia Holowaty Krales

Last week, I found myself on a 5,000-square-foot barge stuck in shallow water in the middle of the Bronx River. As a tugboat attempted to pull us out, its motor dredged up black sludge, trash, and God knows what else. The air stank of rotten eggs. As Cindy Adams always says, “Only in New York, kids!”

This wasn’t your typical barge, either. It’s an art project called Swale, which was created last year by artist Mary Mattingly as a way to grow produce in a public space. So it was a kind of floating garden filled with edible plants, including apple trees planted atop a 6-foot hill. Anyone can board the barge and pick fresh food for free. Being a barge, it can move, and so I tagged along on a trip from Brooklyn Bridge Park, where it was docked for two months, to Concrete Plant Park in the Bronx.

The idea behind Mattingly’s project is to bring foraging to the concrete jungle, where very little fresh produce is grown locally. Mostly, fresh fruits and vegetables are imported and thus expensive. There’s definitely a market for local food: New York City alone is estimated to have over $600 million worth of unmet annual demand for local food. Swale produces about 400 pounds of food per season, Mattingly says — not enough to satisfy even one person’s fruit and veggie intake in one year. So floating barges are unlikely to meet the local food demands on their own — you’d need an armada — but that’s not Swale’s goal. “We don’t see this as a solution,” says Lindsey Grothkopp, who handles external affairs for Swale. “As an art project, it’s here to just propose new models and new ideas.”

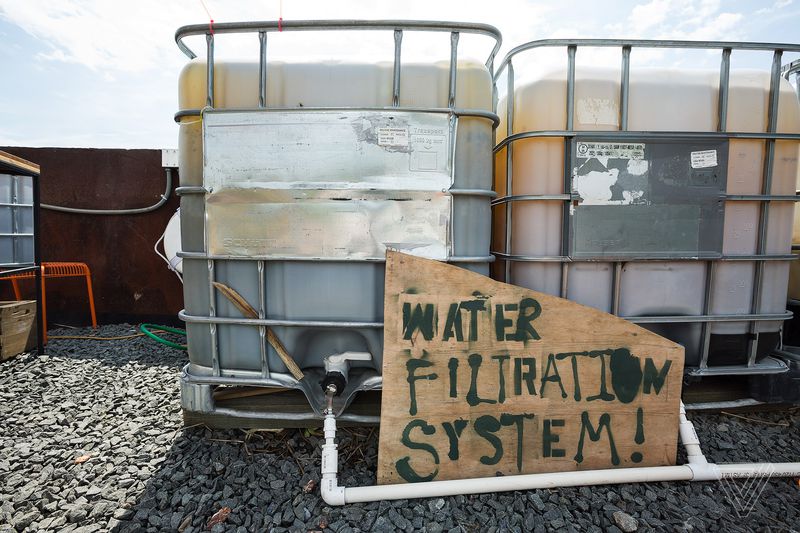

Swale is completely powered by solar panels, and it recycles its own water thanks to a system of pumps and sand filters. It also collects rainwater, and it can desalinate and purify the brackish river water if need be. The barge adds arable land in a dense urban area where land is scarce, and it can float from neighborhood to neighborhood — serving different communities from month to month. Last year, Swale was docked in the Bronx, on Governor’s Island, and then Brooklyn from May to October. (In the winter, it was stored upstate.)

The floating garden is also more accessible than community gardens and rooftop gardens, Mattingly says. On Swale, anyone can board the barge and pick whatever they want, from strawberries and blackberries to kale, lettuce, and chamomile. Most of the city dwellers who visit the floating food forest have never foraged before, says Brittany Gallahan, a college student at the University of Virginia, and Swale’s intern for the summer. They don’t even know where to start. “They’re a little starstruck,” says Gallahan. Whoever is volunteering on board shows them around the garden and gives them some herbs to try in a tea. “They come back with bags and forage,” Gallahan says.

There’s a reason people don’t know how to forage, though: New York City has about 30,000 acres of public parks, but foraging is strictly prohibited by the Parks Department. So most public land in the city can’t be used to grow food. Mattingly launched Swale as a “provocation,” she says: since the barge is floating on water, foraging is allowed there. And it might be working. She’s now partnering with the Parks Department to open the first ever edible garden in a public park in the Bronx, a few feet from where Swale is currently docked. She hopes that the Parks Department will also eventually take over Swale, and keep it docked in the Bronx permanently. That way, she could launch a second barge, doubling the city’s floating farmable area.

For that to happen, though, Mattingly needs money. Like any art project, the barge requires patrons, since it costs $5,000 a month to rent, plus $2,000 a month for insurance. Swale is docking for free, but the overall monthly budget, including rent, insurance, and paying the volunteers who give tours and classes, is about $10,000 a month, Mattingly says. Towing it from place to place costs extra. This year, the barge has been kept afloat mostly thanks to the Parks Department, which helps with rent and pays towing costs. Heineken USA's Strongbow Apple Ciders, which sponsors Swale, also helps with costs, but it’s unclear whether the sponsorship will continue next year — and where the money will come from. “We’re still figuring that out,” Grothkopp says.

For now, Swale is just an art project that is hoping to swing policymakers into growing more food in public spaces. It’s working here in New York City, and when I ask Mattingly if she thinks it could work in other cities in the US, she says yes. Barges could be tweaked to meet the demands of the city hosting them: New York has brackish water, so the garden needs a desalination system. In colder climates, the barge could host a greenhouse. But Boston, Detroit, or Chicago could host a barge only if a rich benefactor could be located to pay for it.

The water has drawbacks, too. After flawlessly floating up the East River — passing by housing projects, high rises, and iconic landmarks like the UN’s headquarters — the barge got stuck in the shallow, stinky waters of the Bronx River. I thought it was going to take hours before we could reach the pier, which was just about 70 feet away. The tugboat — square, skinny, and so tall it looked like a small wave could topple it — dragged the barge backward for a few minutes. Then, dredging up more black sludge, plastic bottles, and cans from the riverbed, it pushed the barge forward again, finally freeing it from the river’s bottom.

When we docked at Concrete Plant Park, the sun was beating down hard. But compared to the concrete pier, Swale’s blueberry bushes, sage, and apple trees provided an island of green. I tried a blackberry from the garden, as well as a bright orange daylily that Gallahan promised me was edible. (There was a little bug inside it, and I ate that, too.) The produce tasted fresh and sweet — if only it didn’t cost so much to grow.

Chicago Synagogue’s Urban Farm Thrives, Feeding Thousands

Chicago Synagogue’s Urban Farm Thrives, Feeding Thousands

July 11, 2017 CHICAGO Aimee Levitt

The farm at KAM Isaiah Israel Congregation in the Kenwood neighborhood of Chicago is very much an urban farm, with a bus line running past the side entrance, and tourists passing by to see Barack Obama’s former home across the street; so, the volunteer farmers do not feel obligated to wake up at the crack of dawn. Still, they prefer to work in the cool of a summer morning, so by 9:30 a.m. on a recent Sunday — farm day — the weekly harvest was well underway.

Half a dozen farmers crouched between the long rows of crops that run parallel to Hyde Park Boulevard, plucking large leaves of collards, kale and mustard, and small black raspberries and red serviceberries. In the synagogue vestibule, pungent with the smell of wild onions, another volunteer sorted the leafy greens and berries into boxes. The day’s yield would total about 50 pounds; later on in the season, when tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers and eggplants are ripe, the volunteers anticipate a harvest five or six times that.

Robert Nevel stood on the front steps of the synagogue, directing traffic and assigning tasks. He wore a big straw hat and a soil thermometer around his neck, which appeared to be some sort of mark of authority: He started the project nine years ago and has led it ever since.

Aimee Levitt | Some of the fruits and vegetables harvested from the KAMII farm.

“What I still find surprising is to see this” — he pointed to the farm — “next to this”; with that he pointed to the synagogue building. “It surprises and pleases me.”

The KAMII farm now comprises two 50-yard-long plots of cultivated crops and two mostly self-sustaining “food forests” — fruit and nut trees, berry bushes and other perennials that can grow without anyone around to tend them — plus two more garden plots at a nearby church and elementary school. In the past nine years, it has produced 22,000 pounds of food, most of which it has donated to shelters and public housing projects in the neighborhood.

Nevel acknowledged that it’s not a lot in the grand scheme of things, but it’s 22,000 pounds of fresh produce that would have otherwise had to have been transported hundreds of miles, costing extra time and money and incalculable damage to the environment. KAMII has a broad definition of the term “food justice”: here, it means not just providing healthy food for everyone in the community, but also helping to maintain environmental stability. KAMII farm manager Owen Needham, who previously worked at a not-for-profit urban farm in Columbus, Ohio, explained that although there are other houses of worship that run urban farms, none — at least that he’s aware of — have as large a program, which is why KAMII serves as model for other synagogues and churches across the country.

The project began in the winter of 2009, around the same time that Michelle Obama, inspired by a 1991 New York Times op-ed by Michael Pollan, announced her plan to revive the White House vegetable garden. The two events were not directly related, but Nevel had also read the Pollan article, and it fit in with ideas about buildings and environmentalism he’d been thinking about since architecture school. He joined in a committee meeting to discuss how to make the synagogue greener.

“Everyone was thinking that the inside of the house of worship was sacred while the outside was profane,” he recalled. “There were so many leftover spaces outside. I wanted everyone to think of those as significant and sacred also.”

At the time, those “leftover spaces” were covered with lawn. Nevel considered the lawn more environmentally friendly than asphalt, but less useful and energy efficient than a food-producing garden. With $700 in seed money from the synagogue’s social justice committee, he and a team of volunteers planted a modest plot in the shape of a Star of David. (“This is a very tidy neighborhood,” said Nevel, “and it was very figural.”) The first crop was rhubarb. Now there are 30 crops, and the project is funded entirely by grants and gifts. This includes operating costs, plus salaries for two staff members: the farm manager and a director of the farm school program that runs for six weeks every summer.

Aimee Levitt | The original Star of David-shaped plot at the KAMII garden.

The farm runs almost all year round, with the bulk of the work happening on Sundays. Seeds arrive every February from a supplier in Winslow, Maine, and the first planting is March 1. Until the weather gets warm, the plants incubate in a makeshift greenhouse that was once the rabbi’s study. The volunteers spend the spring preparing the beds, building trellises, turning over the soil, and installing the drip irrigation system. The first harvest usually comes in June, and the growing season continues until late October. It takes most of the month of November to dismantle the garden. Then it’s time to start planning the annual Food Justice and Sustainability Weekend, which takes place every Martin Luther King Day. And then the cycle begins again.

There are 28 core volunteers, though not all show up every Sunday. About half are KAMII congregants, while the rest come from the community. Being Jewish is not a requirement, but at least one of the volunteers, Aaron Levine, finds it a particular source of pride. “This is what we’re supposed to be doing,” he said, “feeding the community. To me, this is as Jewish as you can get.”

As soon as it began harvesting, the farm began the donation program, which it decided to limit to institutions within a mile radius of the synagogue. The circle contains portions of the Kenwood, Hyde Park, Woodlawn and Washington Park neighborhoods and pockets of both extreme wealth and extreme poverty. In eight years, said Nevel, they’ve never missed a week. “There’s an expectation from the recipients that every week they’ll be receiving fresh food on Sunday,” he explained. “If we don’t deliver, we’re reneging on an established relationship.”

On this particular Sunday, the volunteers prepared donations for the Kenneth Campbell Apartments, a public housing complex for senior citizens, and Door of Hope, a men’s shelter. Each institution would receive three large boxes of greens and six or eight small boxes of berries. Nevel was apologetic about making the deliveries by car; the two institutions were in completely different directions and it was just too difficult to carry 50 pounds of greens on foot. Plus, everything tastes better if you eat it within 90 minutes of harvesting.

Though the recipients are pleased to take whatever food KAMII is willing to provide, they have definite preferences, said Becky Callcott, the volunteer who was responsible for filling the boxes for delivery. “People like collards a lot,” she reported, “but it took a while to get them used to kale.”

At Door of Hope, Nevel spent some time in the kitchen chatting with Matthew Clock, the cook. They couldn’t remember how long they’d known each other, but guessed it was around seven or eight years. Clock grew up in a small town in Mississippi and lamented how many city people are unaware of where their food comes from. He was planning to cook up the kale for that night’s dinner; the collards were hardier and could last a few more days.

Once Nevel returned from making deliveries, he and the other volunteers ate a communal lunch inside the synagogue. Then they planned to work on the other satellite plots, at Reavis Elementary School and the Kenwood United Church of Christ. Later in the afternoon, they would visit a few of the community gardens in the neighborhood and glean the produce that hadn’t been harvested (the community gardeners signal that they’re okay with this by leaving a small white stone in a corner of their plot); they collect about 500 pounds of extra produce every year.

Though Nevel has been doing this every Sunday since the project began, and plans to continue for the foreseeable future, he still marvels over the process. “We start with a 10-pound box of seeds,” he said, “and ten months later, we have four or five thousand pounds of food. It’s a huge leap from soil, sun and water. At the end of the year, it’s really kind of amazing.”

Aimee Levitt reports regularly on Chicagoland for the Forward. Contact her at feedback@forward.com. Follow her on Twitter, @aimeelevitt.

Read more: http://forward.com/news/national/376753/chicago-synagogues-urban-farm-thrives-feeding-thousands/

Farmers For Hire Turn Backyards Into Vegetable Patches

Farmers For Hire Turn Backyards Into Vegetable Patches

By KATHERINE ROTH, ASSOCIATED PRESS | Jun 28, 2017, 3:11 PM ET

This 2016 photo provided by The Organic Gardener shows a rooftop garden in Chicago, Ill. (The Organic Gardener via AP)

Jeanne Nolan grew up in an affluent suburb of Chicago. When it came time to apply for colleges, she shocked her family by opting to skip college and become an organic farmer. Then she brought her farming skills back to the suburbs and city, installing and tending vegetable gardens at clients' homes.

The Organic Gardener Ltd., the farmer-for-hire service she and her husband, Verd, started in the Chicago area in 2005, is one of many such services that have cropped up across the country. Some of these farmers have farming backgrounds, while others are landscapers who expanded their expertise, or entrepreneurs from a range of professional backgrounds who just love gardening and the outdoors.

"If you want serious exercise, you turn to a professional trainer to help you do it right. This is like hiring a gardening coach. Some people say, 'Come over every other week for a year' so they can learn and do it themselves. And I also have a hundred clients whose gardens I've been tending for years who are not even trying to do it on their own, but simply love having it done," says Jeanne Nolan, author of "From the Ground Up: A Food Grower's Education in Life, Love, and the Movement That's Changing a Nation" (Spiegel and Grau, 2013).

Urban farming services cater to both homes and businesses that want home-grown produce but not the work involved in growing it. Clients include apartment complexes, grocery stories, schools, shopping malls, even ballparks.

"It turns out that having home-grown produce is something a lot of people really want," says Jessie Banhazl, founder and CEO of Green City Growers, in the Boston area. The company's Fenway Farms project involves planting and tending vegetable gardens atop Fenway Park, where produce is served to fans at baseball games, and a portion is donated to charity.

Many of her clients are trying to get more engaged in the growing process, she says: "There's something about seeing how food grows, at home, school or even at Fenway, and hopefully this influences dietary choices and has a positive environmental impact."

Dan Allen, CEO of Farmscape, with locations in Los Angeles and the San Francisco area, says farmers for hire have a more intimate relationship with clients than landscapers do. "There's something more personal about growing food," he says.

Hiring a farmer for your backyard isn't necessarily cheap, though (prices vary by region). The farmers admit that if saving money is your goal, it's probably cheaper to just shop organic at the grocery store. But they say the experience of growing your own produce, the learning opportunity for kids — and the bragging rights — make it worthwhile.

Another option: having a farm service visit every couple of weeks to teach growing techniques and offer tips.

"It's surprising how much food you can grow in a very small space. As urban farmers, we grow things vertically and on roofs. We know how to plant crops densely. Even in just a 4-by-4 (-foot) square planter, you can grow a lot of food," Nolan says.

Her company grows " pretty much anything you can imagine," she says. "Our most charismatic are tomatoes, peppers and eggplants. And our season runs from March through mid-December."

To provide enough produce for a family of four, Green City Growers recommends three 3-by-8-foot raised beds.

"Whether it's a median strip or a full backyard, or even containers on a balcony, a vegetable garden can happen almost anywhere," Banhazl says.

On Cleveland’s Largest Urban Farm, Refugees Gain Language and Job Skills

On Cleveland’s Largest Urban Farm, Refugees Gain Language and Job Skills

The Refugee Empowerment Agricultural Program expects to harvest 22,000 pounds of produce this year, while helping refugees find a community.

BY CHRIS HARDMAN | Faces & Visions, Urban Agriculture | 07.05.17

Across the Cuyahoga River from downtown Cleveland, men and women dressed in brightly colored clothing harvest vegetables from tidy rows of plantings. Multilingual conversations take place in Hindi, Nepali, Somali and English. With the Cleveland skyline as their backdrop, these refugee farmers nurture their connection to the land and to their new home.

In 2010, the Cleveland nonprofit The Refugee Response created The Refugee Empowerment Agricultural Program (REAP) to support resettled refugees in the Cleveland area through farming. During the year-long program, men and women from Afghanistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Burundi, Myanmar, and Somalia learn language and job skills as they work the six-acre Ohio City Farm—one of the largest urban farms in the nation.

This year, REAP expects to harvest 22,000 pounds of produce from the farm’s hoop houses and fields. The Refugee Response leases nearly five acres of the Ohio City Farm from the Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority.

Since Donald Trump took office in January, the United States has become a less friendly place for people born in other countries. But various community groups across the U.S. have long supported refugees—often through efforts focused on agriculture.

In addition to REAP in Cleveland, projects such as Plant It Forward in Houston, New Roots in San Diego, and the Refugee Urban Agriculture Initiative in Philadelphia have found that refugees and urban farming are a good fit, and despite the hostility at the federal level, they remain committed to their work.

“We did a survey, and 80 percent of people who were coming as refugees have some sort of agricultural background,” said Refugee Response Director of Agricultural Empowerment Margaret Fitzpatrick.

That makes a farm an ideal entry into the American work force. In addition, Fitzpatrick explained, people are coming from all kinds of backgrounds, often with a history of violence and trauma. Refugees find farm work comforting and therapeutic.

Lar Doe

REAP graduate Lar Doe has been working for REAP since 2012. Although he was born in Myanmar, Doe grew up in a refugee camp on the border of Myanmar and Thailand. After spending nearly 15 years there, he was granted permission to move to the U.S. in 2010. His first jobs were in Kentucky and Iowa, but then he accepted an invitation from the Refugee Response to relocate to Cleveland. He was one of REAP’s first refugee employees.

“It is a diverse city. You can find many different people from different countries,” he said. “I feel like the local people here understand about the world.”

Language and Work Skills

Cleveland has a long history of welcoming refugees; since 1983, 17,000 displaced peoplehave settled in the city. To better serve Cleveland’s increasing population of refugees, 16 organizations pooled their resources to form the Refugee Services Collaborative of Greater Cleveland in 2011. Collaborative members come from county refugee-resettlement agencies, area school systems, healthcare providers, and community and faith-based organizations.

REAP’s current cohort includes 10 refugees from Congo, South Sudan, and Myanmar.

As part of the program, trainees spend 28 hours each week on the farm and 12 hours in the classroom learning English as a Second Language. Farm work includes planting, seeding, harvesting, packing and delivery. For their farm and classroom time, they earn $9 an hour.

“The farm provides a step into employment in an area where people are comfortable (farming) with a skill set that people already have (farming),” Fitzpatrick said. Graduates of the program have gone on to work in the food service industry or been hired to work for REAP itself.

REAP also teaches participants about U.S. workplace culture. “The idea of being to work on time, calling a manager if you are sick, time sheet—those are things we take for granted being U.S. citizens, but these are skills that are not necessarily taught before they arrive,” Fitzpatrick said.

Doe talks about the differences in workplace culture: “[At home,] if you work and you get tired, you can rest, and if you feel OK, you can go back to work,” he said. “I always suggest to new refugees that they have to be patient, because the way that they work in their home country might be totally different than here.”

Integrating into the Community

Located on the west side of the city, next to public housing and across the street from the city’s oldest farmers’ market, the farm is ideally positioned to help integrate refugees into the diverse fabric of American life.

“I’m very fortunate to have this job here, because this is an opportunity that I can get involved to the community and also learn more about the people and culture,” Doe said.

Refugees have the opportunity to practice English with visitors touring the farm, with Americans volunteering on the farm, with REAP staff, with members of REAP’s 60-person CSA, and with customers at the weekly farm stand.

Before coming to Cleveland, Doe worked at a meat packing plant. “The job I used to work before, it was hard to get involved in the country,” he said. “You only go to work and come back. You may never feel like it is your home.”

The community aspect of the program also appeals to Lachuman Nopeney, a 52-year-old refugee from Bhutan who spent 20 years in a refugee camp in Nepal and came to the U.S. in 2009 with no work experience and few English skills.

He worked at a restaurant in Milwaukee, where talking wasn’t encouraged. After going through REAP in 2016, however, he was hired by The Refugee Response to work on the farm.

“I’m happy,” he said with a broad smile. With the help of Refugee Response staff and other refugees, he is learning English. He likes his job of “working, joking, talking.”

“It’s more than a job,” said Refugee Response Executive Director Patrick Kearns. “The people in the program become like family to each other.”

According to Fitzpatrick, Cleveland is a diverse city that celebrates different cultures. As a result, The Refugee Response has formed solid partnerships with area restaurants including Great Lakes Brewing Company, Urban Farmer, and The Flying Fig. In addition to buying produce, these and other local restaurants hold fundraising events, host dinners on the farm, and even employ REAP graduates. As one of the founders of the Ohio City Farm, the Great Lakes Brewing has a special interest in REAP and currently pays REAP to grow vegetables, herbs, and hops on the restaurant’s one-acre parcel of the Ohio City Farm.

“We’re very fortunate to be surrounded by a lot of local food restaurants here in Cleveland,” Fitzpatrick said.

Lar Doe says he is proud of his job. “I want to do something for the community,” he explains. As a refugee and a relatively newcomer to the country, his options to help build community may be limited. “English is the big issue for me. This [farm] is about the only thing we can do to make the city proud.”

Photos courtesy of The Refugee Response.

Farmers Grow A New Stream of Revenue Through Vertical Farming

Farmers Grow A New Stream of Revenue Through Vertical Farming

Combining hydroponic techniques with new timer control innovations

In January, the open fields of Harvard, IL, a far northwestern suburb of Chicago, are biting and bone-chilling. Inside Kirk Cashmore’s barn, it is a fair 72 degrees F, the perfect temperature for producing leafy heads of lettuce through vertical hydroponics, the practice of water-based gardening with vertically stacked shelving in a controlled environment.

Since 2011, Kirk Cashmore has been the only for-profit vertical hydroponic farmer in Northern Illinois. His pesticide- and chemical-free lettuce is served at a popular, Green-certified restaurant, Duke’s Alehouse and Kitchen, in nearby Crystal Lake, IL, and sold at biweekly basket drops along the North Shore and in the Madison, WI metro area.

“Working for my grandfather as a big acre farmer for many years taught me how things worked. I always knew I wanted to be a farmer, but wanted to take a different approach to it. I didn't have the capital or the money to buy big acres to start a traditional farm, so I went around the Midwest and looked at farms that were growing hydroponically and figured out how to start my own,” said Cashmore.

A Growing Industry

According to a recent market research report, the vertical farming market is estimated to be valued at 5.8B U.S. dollars by 2022, growing at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 24.8% between 2016 and 2022. Factors driving growth of the vertical farming market include generating high quality food without the use of pesticides, less dependency on the weather for production, a growing urban population, an increase in the year around production of crops, and reduced impact on the environment.

“The beauty of hydroponic farming is there really is no downtime… I have assets throughout the whole winter and am the only game in town when it comes to winter production of lettuce, Swiss chard, kale, and all the small greens that can be harvested hydroponically,” he remarked. None of his yield is ever wasted. Unsold, yet still edible, greens are donated to a local food pantry and wilted or damaged heads are sent to the compost bin.

Inside Cashmore’s 3,500 square foot building, three vertically stacked shelves, built from recycled materials, provide room for up to 4,000 heads of lettuce. Each shelf grows approximately 1,200 heads, or about five heads per square foot, which Cashmore reports is the number to beat in the world of vertical hydroponics. With room in his barn to still expand out- and upwards, Cashmore has the potential to harvest nearly 8,000 heads.

Plants are seeded in rockwool, a lava-like medium that allows for more oxygen than does soil or water, and an ebb and flow pumping system supplies water to the roots. Cashmore checks pH levels daily.

Winter in the Midwest means long periods of grey, cloudy skies. An electronic timer ensures lights remain on based on the amount of sun, typically 16 hours a day, 7 days a week. Relying on the timer to turn lights on and off as needed gives Cashmore – a one-man show – the freedom to tend to other business without worrying. “Timers are very important for turning lights and fans on and off,” stated Cashmore. “Having an electronic timer makes this an automated sport, so I can have more time with my family and friends. It gives me more time to not have to work.”

He also believes that ensuring a good supply of oxygen is absolutely vital to growing success. Floating rafts of lettuce -- or any system where roots are permanently soaked in water -- offer little available oxygen since the solubility of oxygen in water is remarkable low. Cashmore monitors how much oxygen his roots have and uses an ozone system to kill bacteria, control oxygenation, and keep the water sanitized. This has eliminated the need to use chemicals such as chlorine or hydrogen peroxide.

“I find that if something is worth doing, it's worth doing right. As a father of three little girls, I have no tolerance for chemicals going home and into my kids’ mouths. I want to make the best produce that I can for my family, my clients and my friends,” he explained.

Organically Grown Produce That’s Bug-Chemical-and Pesticide-Free

One of the biggest benefits of hydroponic farming is the superb quality of the produce. Plants don’t spend any time outside in the wind, dirt or the rain; they grow in a controlled environment that is bug-, chemical- and pesticide free. This creates greens with an unmatched body and texture. As more and more people buy organic and seek out locally grown produce, demand is certain to grow. Cashmore envisions remaining profitable and productive by adding more capacity to double or triple lettuce headcount and growing a variety of other vegetables in the winter.

“From school field trips to other farmers and private citizens, there’s an increasingly large interest in my hydroponics facility. I hope to see more vertical hydroponic farms popping up in the area over the next decade.”

Do you have a budding interest in vertical hydroponic farming? Learn more with an in-depth look at Kirk Cashmore’s farm.

Hydroponic Farm Puts Down Roots In Springfield's Gasoline Alley

The indoor farm, located in a section of the city known as Gasoline Alley because of the huge fuel storage tanks that dot the landscape, is one of several businesses operating out of a quirky set of buildings owned and managed by entrepreneur Joseph Sibilia.

Hydroponic Farm Puts Down Roots In Springfield's Gasoline Alley

Updated on July 5, 2017 at 7:34 AMPosted on July 5, 2017 at 7:33 AM

Gallery: Urban Artisan Farm

BY CAROLYN ROBBINS | crobbins163@gmail.com

Special to The Republican | SPRINGFIELD

Call it an island in a food desert.

That's how former chef Tony Renzulli and business partner Jack Wysocki think of their new business, Urban Artisan Farm, which uses hydroponic technology to produce 100 heads of lettuce a week in a greenhouse complex at 250 Albany St.

The indoor farm, located in a section of the city known as Gasoline Alley because of the huge fuel storage tanks that dot the landscape, is one of several businesses operating out of a quirky set of buildings owned and managed by entrepreneur Joseph Sibilia.

It may seem an unlikely spot for a hydroponic farm. But for Renzulli, whose vision is to bring fresh produce to low-income neighborhoods year-round, it's perfect. There aren't many places in the Armory-Liberty Street neighborhood where residents have easy access to fresh vegetables, he said.

Eventually, Renzulli hopes to expand the hydroponic concept to abandoned structures throughout the city with the goal of providing fresh produce and jobs to residents of low-income neighborhoods.

Wellspring Harvest breaks ground for greenhouse

The 2-acre facility means that the old Chapman Valve site in Indian Orchard is being reused.

For now, Renzulli and Wysocki are content to bring the farm's weekly yield of fresh greens to local farmer's markets, including a downtown location. They offer red and green Bibb lettuce and microgreens, which are immature but edible leaves.

They are currently building new structures at Gasoline Alley to expandtheir growing capacity. They also plan to add the cultivation of cucumbers and tomatoes to their year-round operation.

We Are Building A Farm Out of Shipping Containers in Downtown Mobile

We Are Building A Farm Out of Shipping Containers in Downtown Mobile

JULY 2, 2017

“We are building Shipshape Urban Farms, eight hydroponic farms, on St. Michael Street in downtown Mobile. The whole space is the equivalent of a 20-acre farm on less than 1/4 of an acre and over 56,000 plants can grow at once. We will harvest nearly 9,000 heads of lettuces, herbs, leafy greens, and small vegetables a week and the growing season is 365 days a year. The farm is built from repurposed shipping containers because shipping containers were developed in Mobile in the 1950’s. The first harvest will be the end of November or the first of December. We can also host garden parties and events there.

Baldwin County was all farmland when I was a kid and now it is track houses. We are creating a way to take farmland back in a very small space by growing vertically instead of horizontal and using three-dimensional space. We have also taken out environmental pressures by using LED lighting and drip irrigation systems so plants don’t have to grow in soil. Everything is dense and the root structure sits in a permeable mesh. The water recycles through, it gets to the bottom and goes back up again, so we use the equivalent of 10 gallons of water a day. That is 90 percent less water than a traditional farm. We will be non-GMO and won’t use any pesticides

We will also grow herbs on a vertical wall that is about 700 square feet. We are doing an annual CSA, which is Community Supported Agriculture, and people can buy a share of a crop. It is a way to keep food local and support farmers.

Angela and I have been working on this for nearly two years. I have a background in landscape architecture and urban planning and she has a background in horticulture and she researched hydroponics. I worked for the Bloomberg team and went to work for Auburn as an adjunct professor then we started Shipshape. I am an Iraq war vet and this will have a certification for Homegrown Heroes, certifying this farm is produced by a veteran family. Starting a business is stressful and financing is challenging. It took a while to get our first dollar and show the banks that Mobile wants this. People can support it now by signing up for the CSA.

“This farm has been the focal point of all of our conversations the last two years. We had to figure out how to do bring this to Mobile. We are lucky that our backgrounds compliment each other.”

“We plan to sell to restaurants downtown, farmers markets, and directly to the consumer through CSAs. A lot of the local restaurant owners are interested. Nothing that is worth doing comes easy. Several years ago, people thought we were crazy to live downtown, now everyone thinks it is amazing and asks how they can get an apartment. It is cool to be in Mobile at this time. We are 20 years too late to hit the big cities like Seattle and Austin but you can make a” big difference here. Downtown Mobile two years from now is going to be a very different place from where it is today. It is totally different than it was two years ago.”

“We talked about going to a big city where it would be easy to start this farm, but we wanted to stay here and bring it home. We would like to expand it to other areas on the Gulf Coast.I look forward to seeing our name on a chalkboard outside of a restaurant. It gives me chills thinking about it.”

“Science brought us together. We met in a Biology lab at Faulkner. I walked into class late and she was sitting in the front row. I sat next to her because I thought she was cute.”

“We started as study buddies. I am sure we made the people behind us want to throw up. We were taking night classes and the labs were long. We had the highest grades in the class because studying was an excuse to be together. I guess it worked.”

(You can support Shipshape Urban Farms by joining their CSA)

These Kale Farming Robots In Pittsburgh Don't Need Soil Or Even Much Water

These Kale Farming Robots In Pittsburgh Don't Need Soil Or Even Much Water

AARON AUPPERLEE | Monday, July 3, 2017, 12:09 a.m.

Brac Webb, CIO, Danny Seim, COO, Austin Webb, CEO, Austin Lawrence CTO, of RoBotany, an indoor, robotic, vertical farming company started at CMU sells their products at Whole Foods in Upper Saint Clair,

Friday, June 30, 2017.ANDREW RUSSELL | TRIBUNE-REVIEW

Robots could grow your next salad inside an old steel mill on Pittsburgh's South Side.

And the four co-founders of the robotic, indoor, vertical farming startup RoBotany could next tackle growing the potatoes for the french fries to top it.

“We're techies, but we have green thumbs,” said Austin Webb, one of the startup's co-founders.

It's hard to imagine a farm inside the former Republic Steel and later Follansbee Steel Corp. building on Bingham Street. During World War II, the plant produced steel for artillery guns and other military needs. The blueprints were still locked in a safe in a closet in the building when RoBotany moved in.

Graffiti from raves and DJ parties once held in the space still decorate the walls. There's so much space, the RoBotany team can park their cars indoors.

But in this space, Webb and the rest of the RoBotany team — his brother Brac Webb; Austin Lawrence, who grew up on a blueberry farm in Southwest Michigan; and Daniel Seim, who has pictures of his family's farm stand in Minnesota, taped to the wall above his computer — see a 20,000-square-foot farm with robots scaling racks up to 25 feet high. This farm could produce 2,000 pounds of food a day and could be replicated in warehouses across the country, putting fresh produce closer to the urban populations that need it and do it while reducing the environmental strain traditional farming puts on water and soil resources.

“It's the first step in solving a lot of these issues that are already past the breaking point,” Austin Webb said.

RoBotany is a robotics, software and analytics company aiming to bundle its expertise to make indoor, vertical farming more efficient and economical.

Webb left a job as an investment banker in Washington to attend Carnegie Mellon University's Tepper School of Business in hopes of founding a startup around food security issues. While in D.C., Webb volunteered at the Capital Area Food Bank and donated to food security causes.

At Tepper, he met Daniel Seim, an electrical and computer engineer pursuing his MBA. Seim connected with Webb on his mission. The pair teamed up with Lawrence, who left a prestigious Ph.D. program at Cornell to found RoBotany, and brought in Webb's brother, a self-described nerd who taught himself to code at age 12 and turned into a software and high tech engineering whiz.

The team speaks the same language when it comes to why they formed RoBotany. The population is growing. Traditional farming degrades soil and pollutes water. Current vertical farming takes a lot work and doesn't use labor and space efficiently.

Austin Webb said RoBotany seeks to solve all of those problems. His brother, Brac, said it must.

“This is probably one of the first problems humanity needs to solve,” Brac Webb said.

The company started in June 2016 with its first farm in a conference room at Carnegie Mellon University's Project Olympus startup accelerator in Oakland.

The first version of the farm was 50 square feet and produced about a pound of micro leafy greens or herbs a day. Once the farm was up and running, RoBotany supplied arugula and cilantro to the Whole Foods in the South Hills under the brand Pure Sky Farms. The team delivered its latest produce Friday.

“The company aligns well with our mission of providing high quality, locally grown produce and we are excited about the success of their vertical growing method for urban environments,” said Rachel Dean Wilson, a spokeswoman for Whole Foods.

In February, the company expanded, big time. The team leased 40,000 square feet of warehouse and office space from the M. Berger Land Co. on Bingham Street. Version two of the farm is taking shape in one corner of the warehouse. It will be 2,000 square feet and produce 40 pounds of food per day. Version three is in the works. The team hopes it will be 20,000 square feet and produce 2,000 pounds of food today.

“It does speak to a different form of agriculture,” Lawrence said.

In a RoBotany farm, robots move up and down high racks moving long, skinny trays of plants into different growing environments. The amount and color of LED lights can be controlled. So can the amount and make-up of the nutrient-rich mist sprayed directly onto the roots of the plants.

The plants — micro versions of leafy greens like kale, spinach and arugula and herbs like cilantro and basil — grow in a synthetic mesh rather than soil. The roots hang freely from the bottom of the trays.

Plants grow two to three times faster than outdoors, Austin Webb said. They use 95 percent less water. And they have the nutritional value and taste to rival any traditionally grown produce, he said.

The company has raised $750,000 to date and hopes to raise $10 million when it closes its first round of financing this summer to begin construction of the big farm. The team hopes to have it up and running by the winter.

Austin Webb anticipates hiring seven to 10 people to work the farm when the full version is running. Another four to 10 people will be needed to run the business end of the company and maintain the robots and software. The robots will do the dangerous work, moving around trays high in the air.

Eventually, RoBotany will expand its crops to include other fruits and vegetables.

“You can't just feed the world on lettuce,” Austin Webb said.

Aaron Aupperlee is a Tribune-Review staff writer. Reach him at aaupperlee@tribweb.com, 412-336-8448 or via Twitter @tinynotebook.

Farm On Wheels Will Deliver Fresh Produce to Indy Food Deserts

Farm On Wheels Will Deliver Fresh Produce to Indy Food Deserts

Maureen C. Gilmer , maureen.gilmer@indystar.com

Published 7:00 a.m. ET June 30, 2017 | Updated 7:09 a.m. ET June 30, 2017

Brandywine Creek Farms Rolling Harvest truck made its debut at the to serve Indy food deserts Circle Up Indy event at IPS School 51 in Indianapolis on Saturday, June 24, 2017. Michelle Pemberton/IndyStar

'I want to see more farmers come together to end hunger'

Jonathan Lawler planted a seed a year ago that has multiplied into so much goodness even he is surprised.

The Greenfield farmer decided last spring to turn a chunk of his livelihood into a nonprofit with the goal to feed the community. Brandywine Creek Farmswas a leap of faith, but its yield is poised to touch all corners of Central Indiana.

"My job as a farmer is to feed the world, and we have people going hungry in my backyard," Lawler said at that time.

Now, he has partnered with two local hospitals to take his farm on the road.

The Rolling Harvest Food Truck, sponsored by Community Health Network, will take fresh, locally produced food into communities where it is scarce, particularly on the city's east side. It will be offered at little to no cost to those it aims to serve.

"Jonathan came to us with his mission of improving access to food for those in food deserts," said Priscilla Keith, the hospital's executive director for community benefit. "But in addition to providing food, he also wants to educate the community, particularly children, about how food is grown, what kinds of food grow here and to let them know fresh food is best if you can get it."

The 30-foot trailer packed with 6,000 to 7,000 pounds of fresh produce harvested at Lawler's Greenfield farm and at an urban farm on the east side will make weekly (or more frequent) stops at four east-side locations: Community Hospital East, 1500 N. Ritter Ave.; Community Alliance of the Far East Side Farmers Market (CAFÉ), 8902 E. 38th St.; The Cupboard Pantry, 7101 Pendleton Pike; and Shepherd Community Center, 4107 E. Washington St.

Eventually, the program could be expanded to the hospital's north and south sites.

Community pitched in $25,000 for some of the pilot program's expenses, while Lawler has invested his time, his expertise and, above all, his heart.

"I've come to the conclusion that hunger is a business for some organizations, and as an American farmer, I want it to be a thing of the past in this country," said the 40-year-old father of three. "I want to see more farmers come together to end hunger because we are the ones who can do it."

Elijah Lawler from the Rolling Harvest truck and Brandywine Creek Farms gives out free tomato and pepper plants during the trucks debut during the Circle Up Indy event at IPS School 51 in Indianapolis on Saturday, June 24, 2017. The Rolling Harvest truck will make weekly stops at east side locations that are being hard-hit by Marsh closings. Michelle Pemberton/IndyStar

Lawler is working with Hancock Health on a similar program dubbed Healthy Harvest, which will travel into Hancock, Madison, Henry and Shelby counties. Hospital CEO Steve Long said the initiative is part of the Healthy 365 movement in Hancock County.

Both harvest trucks will help chip away at food access problems and point people back to the country's agrarian roots through education, Lawler said.

Inside the temperature-controlled Rolling Harvest trailer are vertical growing towers, so visitors can learn how food grows without going to the farm. An educational staffer will be on site at each stop to talk about the benefits of fresh food.

"Food is actually growing in the dirt; it's as fresh as fresh can be," he said. "The towers will be unloaded at every market, and people will be able to see their food growing and harvest it right there."

Keith said the partnership will help address some of the social determinants that affect the health of the hospital's patients and the larger community, and it advances Community's goal of treating patients more holistically.

"We are really encouraged that we have had not just one, but two health partners who now share the philosophy that real food is the best medicine," Lawler said.

Walkscore.com ranked Indianapolis last among major U.S. cities for access to healthy foods in a 2014 study. Only 5 percent of residents live within a five-minute walk of a grocery store. The lack of access to healthy food on the east side has recently become more acute with the closings of the Marsh grocery stores at 21st Street and Post Road and at Irvington Plaza.

This summer, Lawler also is working with Flanner House community center on the northwest side to establish a working urban farm to feed the neighborhood. Flanner Farms sprouted from a dream of center director Brandon Cosby and food justice coordinator Mat Davis to ease the food insecurity that threatened to rob the neighborhood residents of their independence.

"After looking at the food desert issue, we decided to encompass education more into our mission, along with distribution," Lawler said. "Almost everything our society is doing to address hunger is acting as a Band-Aid. I believe that education and local agriculture can be a solution."

More About Urban Agriculture:

This urban farm will feed an Indy food desert

How Hamilton County gardeners are helping feed their hungry neighbors

Call IndyStar reporter Maureen Gilmer at (317) 444-6879. Follow her on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Amazon's Expansive Biodomes Get Their First of 40,000 Plants

When Amazon began building its new campus five years ago, it insisted on incorporating nature in the design.

Amazon's Expansive Biodomes Get Their First of 40,000 Plants

1/8Amazon is building three spheres in downtown Seattle.NBBJ

RON GAGLIARDO JUST might have the most unusual job at Amazon. He spends most of his time tending to the thousands of plants destined for the Spheres, the 90-foot bulbous glass dome in the middle of Amazon’s sprawling campus in downtown Seattle.

Last week, Gagliardo watched as workers pulled an Australian tree fern off of an Amazon Prime truck, carried it through a particularly wide door in one of the spheres, and plopped it into the soil. Australian tree ferns are hardy, primordial plants that can reach 50 feet tall and "a favorite among greenhouse staff," says Gagliardo. This particular specimen spent three years growing in Amazon's conservatory at the edge of town. It is the first of the 40,0001or so plants destined for the domes, which open next year.

Maybe it’s all the screen time or mounting evidence that employees excel when surrounded by nature, but tech companies suddenly love plants. Airbnb installed a living wall in the lobby of its San Francisco headquarters. Apple wants a small forest of 8,000 trees at its new campus in Cupertino. Adobe incorporated biophilic design into its offices in San Jose, California. Yet they all pale compared to Amazon and its three conjoined spheres, which are both meeting rooms and conservatories that will house more than 400 species of rare (and non-rare) plants.

When Amazon began building its new campus five years ago, it insisted on incorporating nature in the design. Employees can open windows in Doppler, the 38-story tower downtown. Plazas teeming with trees dot a campus of 30 buildings. Dogs romp in a park designed just for them. And then there are those spheres, designed to bring the outdoors indoors within the confines of an office building. “The question was, how do we do this in a significant way,” says Dale Alberda, a principal architect at NBBJ, the firm behind Amazon’s new campus. “Just bringing plants into the office wasn’t going to cut it.”

The designers explored hundreds of shapes before choosing spheres. “It’s the most efficient way of enclosing volume,” Alberda says. The domes, made of glass panels on a steel frame, create enclosed biospheres that combine work and nature. That created a challenge, though, because plants and humans like different things. Plants thrive in warm, muggy environments. Humans do not. Amazon may love nature, but it still needs productive employees, so it compromised: The domes remain a pleasant 72 degrees with 60 percent humidity during the day, while at night they're a more plant-friendly 55 degrees with 85 percent humidity.

“It’s people first,” says Gagliardo. “Then we figured out what plants we could put around people.” Gagliardo started with plants found in similar climates. Mid-elevation regions like the cloud forests of Ecuador, Costa Rica, and parts of China fit the bill. A crew will carefully crane a 60-foot tree from California into the domes next month. Once gardeners and horticulturalists plant everything, the dome and its 60-foot living wall will house vegetation from more than 50 countries.

Some of those plants, like moss, ferns and calatheas, have no problem with low light. Others, like the African aloe tree, require full sun. The architects shunned the triangular panels you may know from Buckminster Fuller's famed geodesic dome in favor of the five-sided panels of a pentagonal hexecontahedron. That resulted in larger panels, which allows more sunlight into the sphere. Ninety LED fixtures with light sensors provide additional lighting when necessary.

All those plants need a lot of water, a task Gagliardo prefers to do by hand. “The collection is so diverse that putting everything on automatic sprinklers would be really difficult,” he says. Each day his team of horticulturists will wander the domes amid executives taking walking meeting and office drones doing whatever Amazon's office drones do, tending to plants and rooting around in the dirt. "It's a dream job," Gagliardo says. "I never would have thought I'd be here at Amazon doing horticulture."

1UPDATE 11:55 AM ET 05/6/2017: This story has been updated to accurately reflect the number of plants in Amazon's Spheres

A Night of Chamber Music On Brooklyn’s Floating Food Forest Showed What Cities Can Be

A Night of Chamber Music On Brooklyn’s Floating Food Forest Showed What Cities Can Be

Music platform Groupmuse brought chamber music lovers to the Brooklyn waterfront Wednesday night. It was nice.

By Tyler Woods / REPORTER

Warp Trio's Josh Henderson plays violin on Swale | (GIF by Tyler Woods).

There is something about being on top of the water, surrounded by plants and music to remind you that New York is actually a place on land on the Earth and not a mindset or abstraction.

That was the case Wednesday night, as classical music ensemble the Warp Trio played violin and piano on Swale, New York’s floating food forest, currently docked on Pier 6 at Brooklyn Bridge Park. The ensemble played Ernest Bloch, an improvisation on water, and “Estrellita (My Little Star)” by Manuel Ponce, in an event organized by the online performance platform Groupmuse.

The location was Swale, a farm located on a barge in the East River. It’s both an art piece and a urbanist project, spearheaded by the artist Mary Mattingly. Visitors to Swale are able to explore the forest of edible, perennial plants. The idea is to create a hugely collaborative project that brings together different communities working toward the same goal, and to provide a sort of minimum viable product for how to conceive of a greater system of locally grown food in big cities.

Swale won our Brooklyn Innovation Award last year as the best artist/creative group in the borough working in the innovation space.

The Warp Trio plays Swale. (Photo by Tyler Woods)

“We’re interested in hosting and being a platform for communities that gather and care about each other,” Marisa Prefer, Swale’s education manager, explained. “Groupmuse found us and we were happy to host.”

Groupmuse is a fairly new platform for hosting classical music concerts in small venues like living rooms or other small, nontraditional spaces. We covered Groupmuse, cofounded by a 27-year-old chamber music lover living in Bushwick, late last year.

“Once in a while we decide to do one in public places, but in keeping with the same ethos, which is informal and intimate,” Groupmuse’s cofounder Sam Bodkin explained.

Swale’s Marisa Prefer explains clover and nitrogen. (Photo by Tyler Woods)

As the sun set behind the statue of liberty Wednesday night and the air cooled, the 50 or so attendees on the barge nestled into the wood chips on the ground, steadied themselves on the edges of the barge, and leaned up against the apple trees on Swale.

“It’s a great way to meet new people,” explained Dennis Lin, one of those sitting on the wall of the barge. Lin is also a Groupmuse performer. He’s played living room concerts around Brooklyn and the city. “It’s being able to perform in a nontraditional way and knowing you’re introducing people to classical music who aren’t used to classical music.”

At the end of the evening, after the lights had come on in the Manhattan skyline, one of the Groupmuse organizers asked each member of the audience to shake the hand of someone near them and say one word about how they were feeling.

“Nice,” the person next to me, Elyse, said. Then the audience disembarked from the barge, walking up a metal gangplank, and went their separate ways into the Brooklyn night.

Farming Takes Root In The City

Long the domain of rural areas, commercial farming operations are now starting to take root in urban neighborhoods.

Farming Takes Root In The City

By Gerry Tuoti

Wicked Local Newsbank Editor

Posted Jun 23, 2017 at 2:13 PM | Updated Jun 23, 2017 at 3:18 PM

THE ISSUE: The state Department of Agricultural Resources is preparing to award grants to urban farming projects. THE IMPACT: In five years, the DAR has awarded nearly $1.5 million in grants for 51 projects and nearly 20 organizations.

Long the domain of rural areas, commercial farming operations are now starting to take root in urban neighborhoods.

“Demand has been really strong for this,” said Rose Arruda, urban agriculture coordinator for the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources, which has awarded approximately $1.5 million in urban farming grants over the past five years.

Perched up on rooftops, packed into greenhouses or spread across vacant lots, urban farmers grow a variety of crops to sell to customers in their communities.

High above Boston’s Seaport District, John Stoddard and Courtney Hennessey began farming the roof of the Boston Design Center in 2013. Dubbed “Higher Ground Rooftop Farm,” they lined up several Boston restaurants as customers and sold fresh produce out of kiosks on site at the Boston Design Center.

While working to fine tune his business model, Stoddard decided last year to narrow his focus to supplying smaller numbers of restaurants with fresh ingredients. This year, he’s devoting most of his attention to Boston Medical Center, which hired him to run a 2,300-square-foot rooftop farm that provides produce for the hospital’s food services program and food pantry.

“It’s great that the at the city and state level they are being supportive of trying to figure out how to make urban agriculture work and thrive,” Stoddard said.

Since it launched its urban agriculture grant program in 2012, the state has awarded funding to projects in cities across the state, including Somerville, Salem, Boston and Worcester. The Department of Agricultural Resources will begin reviewing applications for the next round of grant funding in July.

“It’s state money and we want to make sure the money we’re expending is supporting economic development in communities,” Arruda said.

Ed Davidian, president of the Massachusetts Farm Bureau Federation, said he supports the state’s investment in urban farming grants, as long as public funds aren’t being sunk into unviable enterprises.

“I think it’s a good thing, but sometimes you wonder whether the input equals the yield,” he said. “I don’t know if it works on an economic scale, but it could be good in little niche markets. I’m sure it works in some applications and not in others.”

While traditional farms often rely on machinery, it’s not practical to use tractors and other equipment on rooftop farms or in urban settings. For city farms, that means more manpower is often needed. A large portion of their operating costs, therefore, are devoted to payroll.

While community gardens have been around for decades in many cities, commercial urban agriculture is a newer trend.

“A community garden plot is really for personal use,” Arruda said. “An urban farm is a real business. It’s intensively farmed to have produce, vegetables and fruit available for sale in that community.”