Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

For Earth Day, A Look Back At Some of The Best Green Building Designs

For Earth Day, A Look Back At Some of The Best Green Building Designs

April 22, 2017 04:00PM

It’s Earth Day, and there are plenty of ways to celebrate across the city. But while we’ve got you here, why not have a look back at some the most interesting green developments out there?

1. A proposed vertical farm on the High Line

This mixed-use concept at the Rem Koolhaas parcel at 511 West 18th Street would include residences, an art gallery and the kicker: 10 levels of indoor farming terraces. You can read more about the project here.

2. A “net-zero” public school

In 2015, city built a 444-seat Staten Island elementary school that runs solely on the energy it produces, in a project the developer calls a “laboratory for ideas for future construction.” Learn more here.

3. Green architecture

The infamous New York architect Robert Scarano, once banned from building in NYC after making false statements to the city to dodge zoning laws, is back and now he is building green. In 2014, his Brighton Beach project attempted to become the first multifamily structure to score a Living Building certification.

4. Hipster farmers

Eight floors above the ground at Barclays Center in downtown Brooklyn, workers at the condo building at 550 Vanderbilt Avenue are installing plots of soil on a south-facing terrace. The plots will allow residents to grow their own vegetables.

5. Design for modular green skyscraper wins competition

A conceptual high-rise intended for use in sub-Saharan Africa would taking farming vertical and help eliminate hunger. Now, the architects behind the tower, Pawel Lipiński and Mateusz Frankowski, have won the the eVolo Skyscraper Competition for their design. Check it out here.

6. A Parisian garden on top of an old car plant

Parc André Citroën opened for public use in 1992 and was built atop the old André Citroën car manufacturing plant, which functioned from 1915 to 1970. A large lawn anchors the park, while smaller structures like gardens, greenhouses, and meditative spaces act as the park’s border. It’s really beautiful as well.

7. A wooden skyscraper in London

London Mayor Boris Johnson just received a proposal to solve London’s eco-crisis: an 80-story eco-friendly skyscraper made of wood. The project would house hundreds of units of low-cost housing while becoming the second-tallest building in London behind the Shard.

8. A sustainable home within a greenhouse

Stockholm residents Marie Granmar and Charles Sacilotto live in what they call Naturhus – an environmentally friendly house built within a functioning greenhouse.

Houston’s Hope Farms Breaks Ground

Houston’s Hope Farms Breaks Ground

Linked by Michael Levenston

Recipe for Success Foundation celebrated Earth Day 2016 by officially breaking ground on Hope Farms.

Houston’s New Urban Farming Project Will Provide Fresh Produce, Farmer Training, Nutrition Education and Community Gathering Space in Historic Sunnyside

By Jovanna David

Press Release

Apr 22, 2016

Excerpt:

Located on seven acres in the heart of Houston’s historic Sunnyside neighborhood, the new Hope Farms will use organic methods to generate significant food crops in the midst of one of the city’s largest food deserts, while training military veterans to become successful agri-entrepreneurs.

Hope Farms is a critical component in achieving Recipe for Success Foundation’s mission to change the way children understand, appreciate and eat their food and to mobilize the community to provide healthier diets for children.

Visitors got a sneak peak of the Rolling Green Market that will operate from Hope Farms and deliver significantly reduced priced fresh fruits and vegetables directly to families who live in the food insecure neighborhoods of Houston. The Rolling Green Market is an innovative solution to help overcome food insecurity and access issues. Through its mobile outreach and education efforts it will serve as a dynamic, unifying element to Recipe for Success Foundation’s Seed-to-Plate Nutrition Education™ Program and the new Hope Farms.

Shanghai Planning Huge Vertical Farm, Looking to change The Way It Feeds Its 24 Million Residents

Shanghai Planning Huge Vertical Farm, Looking to change The Way It Feeds Its 24 Million Residents

BY ALEX LINDER IN NEWS ON APR 21, 2017 3:30 PM

As Shanghai continues to expand outward, replacing agriculture with urbanization, a US-based design firm is looking to reimagine the way that Shanghai grows food to feed its 24 million people.

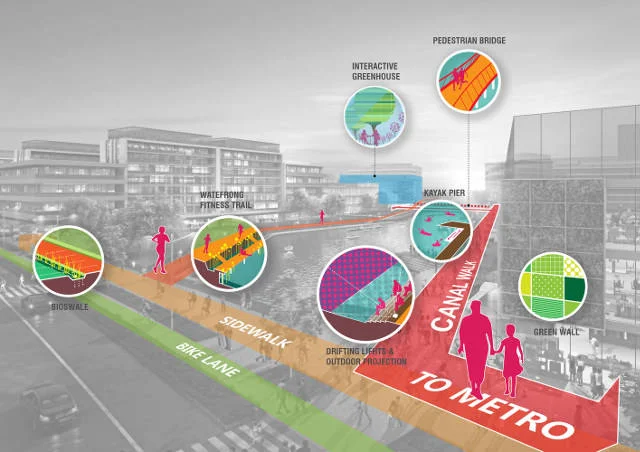

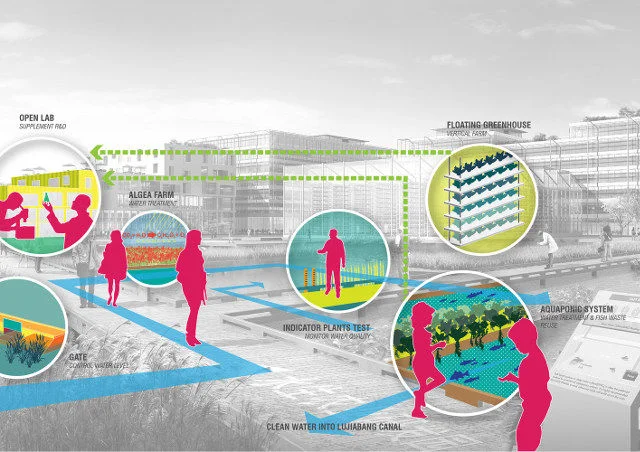

The Sasaki planning and urban design firm is turning heads with its masterplan for a 250-acre urban agricultural district in Pudong called Sunqiao, which will include, most spectacularly, towering vertical farms that grow lots of leafy vegetables

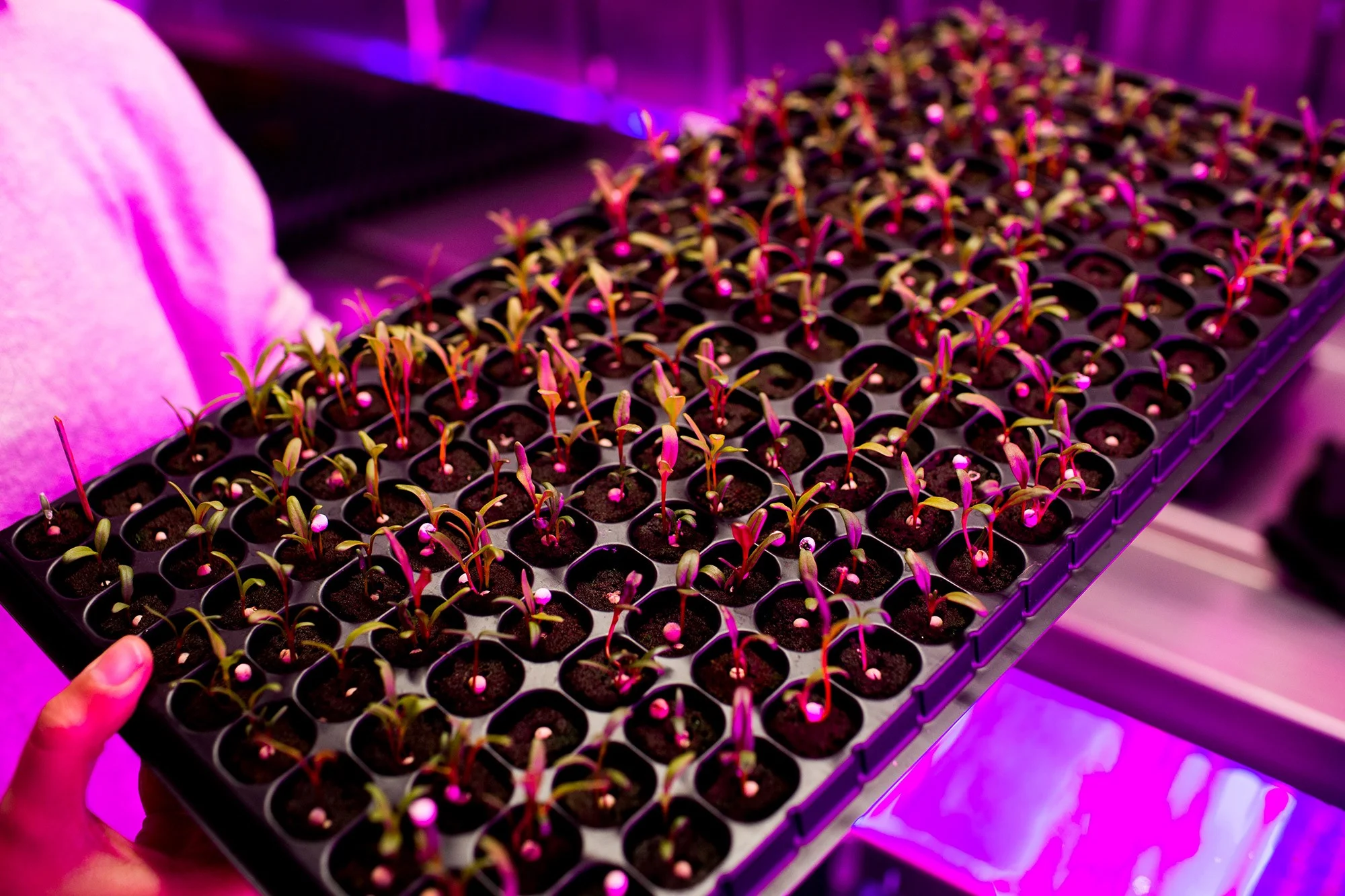

Sunqiao will include residential, commercial and public spaces integrated with an urban farm spread out across several buildings that will hydroponically produce spinach, kale, bok choi and watercress under LED lights and nutrient-rich water. Those veggies will then be sold to local grocers and restaurants.

Michael Grove, a principal at Sasaki, told Business Insider that the firm expects to break ground on the project by 2018, though there is no timeline yet. Grove said that the biggest problem they will face will be designing buildings that block out as little sun as possible.

While this project may seem ambitious, it's not quite on the level of Italian architect Stefano Boeri who wants to cover China with "forest cities" starting with the smoggy Hebei capital of Shijiazhuang

For China, the future certainly looks green.

[Images via Sasaki]

This 100-Hectare Vertical Urban Farm Will Feed 24 Million People

Shanghai is planning an urban vertical farm that will feed millions. The centre aims to educate people on the benefits of food sustainability. Sasaki Architects will create the 100-acre farm that will be interactive and hands-on. The population of Shanghai is 24 million and the company aims to feed every one of them.

This 100-Hectare Vertical Urban Farm Will Feed 24 Million People

SHAWNTAE HARRIS APRIL 20, 2017

BY: SHAWNTAE HARRIS

Shanghai is planning an urban vertical farm that will feed millions. The centre aims to educate people on the benefits of food sustainability.

Sasaki Architects will create the 100-acre farm that will be interactive and hands-on. The population of Shanghai is 24 million and the company aims to feed every one of them.

The biggest city in China lost a lot of green space due to the urbanization of the city. The city lost almost “123,000 square kilometers of farmland to urbanization – a land area equivalent to nearly the entire state of Iowa,” wrote Sasaki. The green space will fit in between the chaos of the big city and tall buildings.

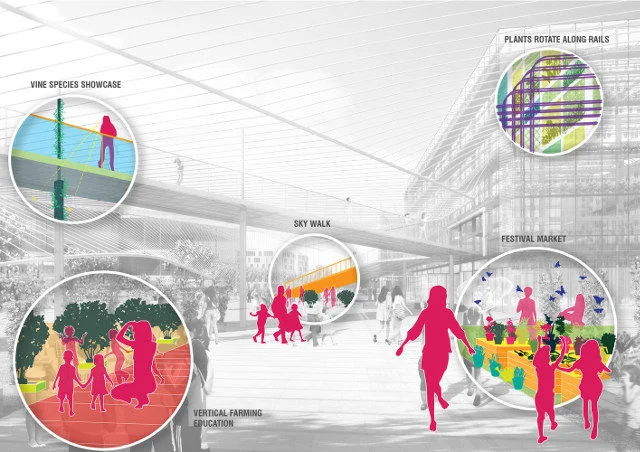

The layout will include growing centers like algae farms, floating greenhouses, vertical walls and seed libraries. “As cities continue to expand, we must continue to challenge the dichotomy between what is urban and what is rural. Sunqiao seeks to prove that you can have your kale and eat it too,” explained Sasaki to Inhabitat.

“This approach actively supports a more sustainable food network while increasing the quality of life in the city through a community program of restaurants, markets, a culinary academy and pick-your-own experience.”

The food sustainability will educate on large scale food production. There will be family-friendly events that will be held to teach kids about the values and importance of food supply.

A tour of the interactive greenhouses and a science museum will be held. As well as a tour of the sea life and plant growth to stimulate the water.

Shanghai needs more hands on food education. In recent years residents of Shanghai have turned creative to create green spaces. Many have built little gardens on their balconies or rooftop to create organic, fresh foods. Without the proper education, Shanghai food sustainability will not prosper.

Shanghai Recently Changed Food Laws

On March 20th Shanghai implemented a new restaurant food safety law, and in the last month the food hotline received over 14,000 calls. This is a 47 per cent increase from last year.

“Some businesses are trying hard to cover up violations. And tip-offs from insiders really save us a lot of time in investigation,” saidShen Ruoqing, head of the Center of Complaints and Reports at the Shanghai FDA. “The recent scandal of the famous bakery Farine is such an example.”

A reported insider told Shen one particular business was hiding expired food in a residential complex, in order to not get caught. Stricter rules will be implemented by the government soon.

In the meantime, the residents of Shanghai can look forward to the new urban farm and the benefits that it will bring to the health and well being of the community.

How Freight Farms Is Taking Off From Boston To Canada

SEB EGERTON-READ · APRIL 19, 2017

Freight Farms sell a solution where 40’ x 8’ x 9.5’ shipping containers are outfitted innovative tools and technologies to produce consistent, high-volume harvests of leafy greens, herbs and a number of other select crops 365 days per year. Based in South Boston, this highly innovative idea was derived by co-founders Jon Friedman and Ben McNamara partly when they discovered that New England, despite its wealth and prosperity, relied on imports from outside the region for close to 90% of its food, while nearly 15% of all households reported not having enough to eat.

Using solar energy to provide the majority of the electricity required to grow crops, the containers are designed to be self-sustaining and are sold to individuals, not necessarily farmers by trade, but people who want to grow food for themselves and/or their community. The freight farm containers are small enough to be squeezed between buildings, placed at the end of parking lots, or almost anywhere in urban terrains.

The Freight Farm equipment set offers a hydroponic system, which they call the Leafy Green Machine, a soil-free growing method that utilised recirculated water with nutrient levels to grow plants. LED lights are optimised for each growing cycle, while a smartphone app called Farmhand allows the container owners to manage conditions remotely and connect with live cameras to monitor the plants.

The idea was simple. Give individuals a base and template to enable a distributed food growing network in cities. Boston may not be the obvious ‘hub’ for farming activity, but Freight Farms has spread across the north-east USA and into Canada, and there are now more than 100 of the company’s containers operating in the US alone.

The container’s growing conditions are controlled via a mobile app. Credit: Freight Farms

Investing and owning a Leafy Green Machine isn’t an inexpensive proposition, rather it’s an entrepreneurial investment opportunity. Purchasing one of the containers reportedly costs a business up to $85,000, while annual operating costs may reach $13,000. However, in a New England context where demand for locally grown food is increasing (close to 150 farmer markets operate in the state of Massachusetts alone), which offers significant business potential for new local growers, especially if they can run on low operating costs with minimal demand for land, water and chemical fertilisers.

In Boston in particular, enabling policy support has been a factor, where a recent mayor legally expanded zoning laws within the city to allow farming in freights, on rooftops and in other specific ground-level open spaces. One of the most overt examples the city’s positive stance on urban farming is at the iconic Fenway Park, where Green City Growers run the 5000-sq ft Fenway Farms above the iconic home of the Boston Red Sox.

There are legitimate questions about the role of urban farming, in particular hydroponic techniques, in the future of food. Will urban farming ever be able to grow the volume and variety needed to account for a significant percentage of the consumption of the city’s inhabitants? The answer to that question is, at best, unknown. However, there’s no doubt that hydroponic, aquaponic and aeroponic urban farming methods are gaining traction because they speak to a new way of thinking about how food is grown, distributed and consumed. In a context where land and water is scarce, and where people are increasingly inquisitive for information about what they eat, it seems increasingly likely that at least some portion of the food consumed within urban areas will be grown by a distributed network across the city in containers, warehouses and rooftops. The story of Freight Farms, and their growth across the north-east USA and Canada is just another hint in that direction.

Innovative, Efficient Indoor Farm In New Jersey

Innovative, Efficient Indoor Farm In New Jersey

By: ALISON MORRIS

POSTED: APR 18 2017 05:41 PM EDT

NEW YORK (FOX 5 NEWS) - Could the answer to the global food crisis be hidden in a warehouse in New Jersey? A local indoor farming startup is producing affordable crops there year-round, independent of the weather.

And food safety is paramount. That means outside clothes or jewelry can't come in. A visit to Bowery's farm starts with a uniform and some hand sanitizer. This vertically integrated farm in Kearny, New Jersey, is producing some seriously clean greens.

CEO and co-founder Irving Fain describes the farm as "post-organic" and says it is completely chemical free: no pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, or insecticides. Fain says it is the purest produce you could possibly get.

Innovative, efficient indoor farm in New Jersey

He founded the farm a few years ago along with David Golden and Brian Falther. They've brought in $7.5 million in funding from some rock star investors, including Top Chef Tom Colicchio.

The farm is now producing crops 365 days a year regardless of the weather, using a lot less water. Fain says it is 100 times more productive than the same square footage of outdoor land. The farm grows twice as fast as the field, with more crop cycles every year, more yield in every crop cycle, and uses 95 percent less water.

Their hope is to help solve the global food crisis. Fain says the planet's population will be 9 billion to 10 billion by 2050, so it will need 50 percent to 70 percent more food to feed everyone.

While that change is happening, 70 to 80 percent of people are living in cities. They saw that urbanization and became obsessed with the question: how do you provide fresh food to urban environments in a more efficient and sustainable way? The answer: start with LED lights. Fain says the lights they use mimic the sun, so it's as if the plant is growing in the absolute healthiest environment for its entire life. He says that the price of those lights dropped while their efficiency went up about 5 years ago, making indoor growing commercially viable.

Fain says Bowery sells 5-ounce clamshells for $3.99 or even $3.49, which is pretty standard, if not lower, than what you find out in the field. Throw in the Bowery Operating System, which creates optimal growing conditions, and Bowery is able to churn out fresh, affordable, and delicious greens.

And the farm is growing. Fain says they're already experimenting with different types of crops and other SKUs outside of the leafy green category.

Right now you can find Bowery lettuce and basil in tri-state Whole Foods and in Foragers Market in New York City. The lettuce you'll find there has often been harvested the same day it hits the shelves.

Urban Gardening Kit Has Everything You Need To Grow Your Own Food

From Ikea’s indoor gardening offerings to a shipping container community farm in Brooklyn, New York,urban agriculture is having quite the moment. Now, GrowKit, billed as an “Urban Agriculture Kit for Beginners,” wants to make farming accessible to city dwellers starved for space.

Urban Gardening Kit Has Everything You Need To Grow Your Own Food

Small spaces welcome

BY SELINA CHEAH APR 18, 2017, 4:17PM EDT

From Ikea’s indoor gardening offerings to a shipping container community farm in Brooklyn, New York, urban agriculture is having quite the moment. Now, GrowKit, billed as an “Urban Agriculture Kit for Beginners,” wants to make farming accessible to city dwellers starved for space.

Developed by Porto, Portugal-based startup Noocity, the kit gives city residents a chance to grow and harvest their own food, even if they don’t have any experience with farming. The compact and portable package includes everything needed to begin an organic, edible garden—from a Growbag with all the necessary equipment and potting soil to a Growpack with the plants and fertilizer. There’s also a set of audio guides, detailing step-by-step instructions.

This garden uses up to 80 percent less water than a conventional vegetable patch because of its sub-irrigation system, which provides water to the plants’ roots. It also has a water reservoir, so the garden can self-water for up to three weeks.

Noocity, which debuted a larger self-watering gardening system called Growbed in 2015, is currently running an Indiegogo campaign for Growkit. One Growkit is going for $74. Here’s the demo video.

Bolloré Logistics Korea Installs Urban Farm

Bolloré Logistics Korea Installs Urban Farm

The company installed an urban farm on its office rooftop building in Seoul, South Korea, as part of the Bolloré’s initiative to promoting “Green Projects” and protecting biodiversity.

April 18, 2017 By Denice Cabel

Bolloré Logistics Korea recently installed an urban farm on its office rooftop building in Seoul, South Korea, as part of the Group’s initiative to promoting “Green Projects” and protecting biodiversity.

Urban farming is a practice of growing your own food in the city, with limited space. Bolloré Logistics Korea has transformed the available rooftop space of its 6-floor office building into an urban farm, optimising current available space resources. This urban farm is split into four parcels and covers a total space of 264 sqm.

Bolloré Logistics Korea signed an agreement with Pajeori, a non-profitable organization, to maintain the farm with volunteers from the nearby neighborhood in order to cultivate each a small parcel of the Urban Garden, therefore making it a community base project as well.

The urban farm is growing organic fruits and vegetables as only natural fertilisers mostly made from rice bran are and will be used. Bolloré Logistics Korea also plans to grow traditional Korean fruits and vegetables which are not always found anymore in big retail stores, as they are difficult to grow and conserve since they require a wide range of unique resources for food and agriculture.

Some honey plants will also be planted in order to attract pollinators. Back in 2016, Bolloré Logistics Korea sponsored a wooden beehive structure (“Honey Factory”) to create awareness of the vital role of bees in our lives as they are a crucial component of food production and are responsible for a third of the food that we eat.

Bolloré Logistics Korea looks forward to harvesting the very first crops in the upcoming months. Fully in line with the biodiversity action plan put into effect within the Group, Bolloré Logistics’ biodiversity strategy has three fundamental pillars based on the ARC concept (Avoid / Reduce / Compensate):

– Embracing biodiversity as one of the company’s environmental concerns;

– Working with customers and suppliers on biodiversity issues and the impact of our activities;

– Make our sites models for biodiversity, all over the world.

Urban Rooftop Farm Powered by Rainwater and Composted Food Waste

#LAUNCHFood innovators Marc Noyce and Brendan Condon of Biofilta shared their closed loop urban rooftop garden concept at the LAUNCH Food forum at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. The video shows a rendering of their closed loop – water, space, and time efficient rooftop concept.

Urban Rooftop Farm Powered by Rainwater and Composted Food Waste

18 APRIL 2017

#LAUNCHFood innovators Marc Noyce and Brendan Condon of Biofilta shared their closed loop urban rooftop garden concept at the LAUNCH Food forum at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. The video shows a rendering of their closed loop – water, space, and time efficient rooftop concept. “We are so excited to share the Foodwall and Foodcube garden design here, amongst some of the world’s leading innovators who are working to transform our global food system to be fairer, healthier, more nutritious and resilient,” says Biofilta’s Marc Noyce.

The system is low tech and uses rooftop rainwater and composted food waste to grow food. The two innovators hope to transform city rooftops into low cost, high yield, water efficient, ergonomic gardens for city dwellers around the world. Biofilta is bringing this system to market in the coming months, and is interested in partnering with the global housing industry in closing the loop and advancing urban farmers.

“We think with good food architecture in cities, we can repurpose food waste and rainwater runoff, and flip cities into becoming food growing powerhouses,” says Brendan Condon also of Biofilta.

With the LAUNCH Food challenge, we called for supply- or demand-side innovations with the potential to improve health outcomes by enabling people to make healthy food choices. 280 innovators from 74 countries answered our call for applications, and our panel of expert reviewers helped us choose 11 of the most promising innovations. Follow the hashtag #LAUNCHFood on Twitter and Facebook to learn about all our innovators.

LAUNCH Food is a partnership with the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s innovationXchange, the U.S. Agency for International Development, and a broad cross-sector network of key opinion leaders and industry players. We take a people-centered approach to action across the whole of the food system.

Sourced with permission from Huffington Post and @idavar

@Biofilta

Elon Musk’s Brother Is Disrupting Farming—One Sprig of Hyperlocal Microgreen At A Time

04.17.17 | 3 HOURS AGO

Elon Musk’s Brother Is Disrupting Farming—One Sprig of Hyperlocal Microgreen At A Time

Elon Musk's brother, Kimbal, cofounded a high-tech company for a very low-tech product—spinach. And also chard and mustard greens and anything else that can be grown in an old shipping container outfitted with $85,000 worth of high-tech farming equipment. Called Square Roots, the idea could shake up the way we think about farming and food production. Its genesis comes from an unlikely source: weed. "Cannabis is to indoor growing as porn was to the internet," says its CEO and cofounder, Tobias Peggs.

Backchannel takes a close look at the new startup that takes the guess work out of growing food. It lets wannabe farmers grow artisanal lettuce in the so-called "nano-climate" of an old shipping container that makes the farms impervious to weather and capable of being run almost entirely via iPhone. The nano-climate has a few other perks, too, including something straight out The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: the ability to design a specific taste in a crop thanks to tech that can precisely control growth factors like light and temperature. Check out the full story here while munching on your hyper-local bag of freshly picked microgreens.

Is Boston The Next Urban Farming Paradise?

The city’s healthy startup culture is contributing to Boston’s rapidly growing reputation as a haven for organic food and urban farming initiatives

The inspiration for Boston-based Freight Farms was launched after co-founders and friends Jon Friedman and Ben McNamara realized that New England currently gets almost 90% of its food from outside the region. Photograph: Freight Farms

Sunday 16 April 2017 10.00 EDT | Oset Babur

For those seeking mild, year-round temperatures and affordable plots of land, Boston, with its long winters and dense population, isn’t the first city that comes to mind.

But graduates of the city’s nearly 35 colleges and universities are contributing to the area’s growing reputation as a haven for startups challenging and transforming age-old industries, from furniture to political fundraising. The city’s strong entrepreneurial spirit, combined with progressive legislation like the passing of Article 89, has also turned Boston into one of the nation’s hubs for urban agriculture.

The inspiration for Freight Farms, an urban farming business headquartered in South Boston, was launched after co-founders and friends Jon Friedman and Ben McNamara realized that New England currently gets almost 90% of its food from outside the region, yet 10-15% of households still report that they don’t have enough to eat. The over reliance on imported produce drove Friedman and McNamara to launch a Kickstarter campaign in 2011 for their farming business, which sells freight containers to would-be farmers, many of whom aren’t necessarily farmers by trade, but are interested in contributing to sustainable living. A Freight Farms container is designed to be largely self sustained, and uses solar energy to provide the majority of electricity required to grow the crops. Julia Pope, who works in farmer education and support at the organization, says people can find the freight containers squeezed between two buildings, in a parking lot, under an overpass, or virtually anywhere in the modern urban terrain.

Freight Farms has spread north from Boston to Canada, and Pope says there are over just over 100 of the company’s container farms operating in the US alone. The company outfits each 40-ft container with the equipment for the entire farming cycle, from germination to harvest. This set of equipment, which the company calls Leafy Green Machine (LGM), creates a hydroponic system, a soil-free growing method that uses recirculated water with higher nutrient levels to help plants grow. Vertical growing towers line the inside of the shipping container, with LED lights optimized for each stage of the growing cycle. Farmers can manage conditions remotely using a smartphone app called Farmhand, which connects to live cameras inside the container.

Freight Farms has spread north from Boston to Canada, and Pope says there are over just over 100 of the company’s container farms operating in the US alone. Photograph: Freight Farms

Pope says that of customers who have purchased the LGM, over 50 have started small businesses, each consistently producing two acres worth of food year-round. One of these businesses is Corner Stalk Farm, which sells locally grown leafy greens – including kale, mint and arugula, as well as over twenty varieties of lettuce, to cater to demand at various farmers markets in Boston and Somerville, the city’s landmark Boston Public Market, and through orders from produce delivery services (such as Amazon Fresh) that are increasingly popular in cities. It’s no small feat to own and operate the LGM: purchasing one of the containers will run an aspiring business $85,000, with operating costs adding up to another estimated $13,000 per year.

Luckily, steady consumer demand, evidenced by over 139 farmers markets across the state of Massachusetts alone, help to offset the high costs to starting and running an urban farm. Hannah Brown, a resident of Boston’s North End, regularly shops at the Boston Public Market, which sells locally sourced goods from over thirty small businesses. “There aren’t many stores with really fresh produce in the immediate area, so it’s definitely filled a need for me,” she says. Brown also finds the small business owners who sell their produce at the market to be an invaluable resource: “It’s great to be able to talk with the people working the produce stands, because they can recommend what’s freshest and how to prepare it.” As a result, she says she’s taken to only buying produce that’s in season and adjusting her habits to align with what’s available to her locally.

The growing popularity of urban farming owes much to a former mayor, Thomas Menino, and one of his final acts while in office. He signed into law Article 89, expanded zoning laws to permit farming in freight containers, on rooftops, and in larger ground-level farms. Article 89 made it possible for those practitioners to sell their locally grown food within city limits.

One business that has taken advantage of Article 89 is Green City Growers, which runs Fenway Farms, is a 5,000-sq ft rooftop farm above Fenway Park. The rooftop is lined with plants grown in stackable milk crate containers, which are equipped with a weather sensitive drip irrigation system that monitors the moisture of the soil in the crates to make sure plants get just the right amount of water. Although the farm isn’t open to the general public, it is visible to fans from the baseball park, and a stop on the Fenway Park tour.

In late 2013, the landscape for urban agriculture in Boston got a lot greener with the passing of Article 89, which made it possible for those practitioners to sell their locally grown food within city limits. Photograph: Freight Farms

Boston is far from alone in passing legislation that makes farming a possibility for city-dwellers. In Sacramento, there are even tax incentives for property owners who agree to put their vacant plots of land to active agricultural use for at least five years, while the city council of San Antonio voted just last year to pass legislation that makes urban farming legal throughout city limits. And while Boston boasts home to various agricultural startups and nonprofits, entrepreneurs in other parts of the country are contributing to a national farming movement in their own ways: Kimbal Musk, brother of Tesla and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk, recently set up a container farm in an old Pfizer factory in Brooklyn, while Local Roots Farms is turning shipping containers into urban farms (using the same hydroponic method that the LGM uses) across the Los Angeles area.

As Bostonians now find themselves with a slew of new options to grow and profit from fresh produce on rooftops and in alleyways, some nonprofit organizations are looking to use urban farming as an educational asset. CitySprouts was born in Cambridge in 2001 after executive director Jane Hirschi identified what she calls “an immense need for children to understand where their food was coming from”. CitySprouts teams up with educators to set aside class time for students to cultivate gardens on school property that they can grow their own food in. There are now over 20 public schools using CitySprouts gardens in the Boston area, and more than 300 public school teachers participating in the fresh food program.

Caitlin O’Donnell, who teaches first grade at Fletcher Maynard Academy in nearby Cambridge, says the program does a great job of giving urban kids the opportunity to interact with their environment in ways they wouldn’t have otherwise, she adds. “Whether students are digging for worms, sketching roots structures, crushing apples for cider, or sampling chives and basil, their hands are busy and their senses are engaged ...what makes City Sprouts most effective (and exceptional) is that it is collaborative and flexible by design.”

Boston’s rise in the national urban farming movement also has helped to make locally grown produce more available to low-income residents. Leah Shafer recalls that she was able to use food stamps at a farmer’s market to receive half-off of her purchases of kale, blueberries, and more.

“It made it possible for me to buy organic, local produce that I otherwise just wouldn’t have been able to afford. I don’t think I would have been able to support local farmers without that discount,” she says.

Kimbal Musk's Tech Revolution Starts With Mustard Greens

A leafy green grows in Brooklyn. (Photo by Natalie Keyssar)

The other Musk is leading a band of hipster Brooklyn farmers on a mission to overthrow Big Ag.

Farmers have always had a tough time. They have faced rapacious bankers, destructive pests, catastrophic weather, and relentless pressure to cut prices to serve huge grocery suppliers.

And now they must compete with Brooklyn hipsters. Hipsters with high-tech farms squeezed into 40-foot containers that sit in parking lots and require no soil, and can ignore bad weather and even winter.

Follow Backchannel: Facebook | Twitter

No, the 10 young entrepreneurs of the “urban farming accelerator” Square Roots and their ilk aren’t going to overthrow big agribusiness — yet. Each of them has only the equivalent of a two-acre plot of land, stuffed inside a container truck in a parking lot. And the food they grow is decidedly artisanal, sold to high-end restaurants and office workers who are amenable to snacking on Asian Greens instead of Doritos. But they are indicative of an ag tech movement that’s growing faster than Nebraska corn in July. What’s more, they are only a single degree of separation from world-class disrupters Tesla and SpaceX: Square Roots is co-founded by Kimbal Musk, sibling to Elon and board member of those two visionary tech firms.

Kimbal’s passion is food, specifically “real” food — not tainted by overuse of pesticides or adulterated with sugar or additives. His group of restaurants, named The Kitchen after its Boulder, Colorado, flagship, promotes healthy meals; a sister foundation creates agricultural classrooms that center a teaching curriculum around modular gardens that allow kids to experience and measure the growing process. More recently, he has been on a crusade to change the eating habits of the piggiest American cities, beginning with Memphis.

“This is the dawn of real food,” says Musk. “Food you can trust. Good for the body. Good for farmers.”

Square Roots is an urban farming initiative which allows “entrepreneurs” to grow organic, local vegetables indoors at its new site in Bed Stuy, Brooklyn. (Photo by Natalie Keyssar)

Square Roots is one more attempt to extend the “impact footprint” of The Kitchen, says its CEO and co-founder Tobias Peggs, a longtime friend of Musk’s. (Musk himself is executive chair.) Peggs is a lithe Brit with a doctorate in AI who has periodically been involved in businesses with Musk, along with some other ventures, and wound up working with him on food initiatives. Both he and Musk claim to sense that we’re at a moment when a demand for real food is “not just a Brooklyn hipster food thing,” but rather a national phenomenon rising out of a deep and wide distrust of the industrial food system, a triplet that Peggs enunciates with disdain. People want local food, he says. And when he and Musk talk about this onstage, there are often young people in the audience who agree with them but don’t know how to do something about it. “In tech, if I have an idea for a mobile app, I get a developer in the Ukraine, get an angel investor to give me 100k for showing up, and I launch a company,” Peggs says. “In the world of real food, there’s no easy path.”

The company is headquartered in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant, right next to the Marcy Projects, which were the early stomping grounds of Jay Z. It’s one of over 40 food-related startups housed in a former Pfizer chemicals factory, which at one time produced a good chunk of the nation’s ammonia. (Consider its current role as a hub of crunchy food goodness as a form of penance.) Though Peggs’ office and a communal area and kitchen are in the building, the real action at Square Roots is in the parking lot. That’s where the company has plunked down ten huge shipping containers, the kind you try to swerve around when they’re dragged by honking 18-wheel trucks. These are the farms: $85,000 high-tech growing chambers pre-loaded with sensors, exotic lighting, precision plumbing for irrigation, vertical growing towers, a climate control system, and, now, leafy greens.

Musk and Peggs (center) with the Brooklyn growers. (Photo by Steven Levy)

Each of these containers is tended by an individual entrepreneur, chosen from a call for applicants last summer that drew 500 candidates for the 10 available slots. Musk and Peggs selected the winners by passion and grit as opposed to agricultural acumen. Indeed, the resumes of these urban farmers reveal side gigs like musician, yoga teacher, and Indian dance fanatic. (The company does have a full-time farming expert and other resources to help with the growing stuff.) After all, the idea of Square Roots is not about developing farm technology, but rather about training people to make a business impact by distributing, marketing, and profiting off healthy food. “You can put this business in a box — it’s not complicated,” says Musk. “The really hard part is how to be an entrepreneur.”

Peggs gave me a tour late last year as the first crops were maturing. The farmers themselves were not in attendance. Every season is growing season in the ag tech world, but once you’ve planted and until you harvest, your farms can generally be run on an iPhone, and virtually all the operations are cloud-based. Peggs unlocked the back of a truck and lifted up the sliding door to reveal racks of some sort of leafy greens. Everything was bathed in a hot pink light, making it look like a set of a generic sci-fi movie. (That’s because the plants need only the red-blue part of the color spectrum for photosynthesis.) Also, the baby plants seemed to be growing sideways. “Imagine you’re on a two-dimensional field and you then tip the field on its side and hang the seedlings off,” Peggs says. “That means you’re able to squeeze the equivalent of a two-acre outdoor field inside a 40-foot shipping container.”

Square Roots didn’t have to invent this technology: You can pretty much buy off-the-shelf indoor farming operations. We owe this circumstance to what once was the dominant driver of inside-the-box ag tech: the cultivation of marijuana. The advances concocted by high-end weed wizards are now poised to power a food revolution. “Cannabis is to indoor growing as porn was to the internet,” says Pegg.

Using light, temperature, and other factors easily controlled in the nano-climate of a container farm, it’s even possible to design taste. If you know the conditions in various regions at a given time, you can replicate the flavors of a crop grown at a specific time and place. “If the best basil you ever tasted was in Italy in the summer of 2006, I can recreate that here,” Peggs says.

So far, the Square Roots entrepreneurs haven’t achieved that level of precision—but they have jiggered the controls to make tasty flora. And they’ve used imagination in selling their crops. One business model that’s taken off has the farmers hand-delivering $7 single-portion bags of greens to office workers at their desks, so the buyers can nibble on them during the day, like they would potato chips. Others supply high-end restaurants. Occasionally Square Roots will run its version of a farmer’s market at the Flushing Avenue headquarters or other locations, such as restaurants in off hours.

The prices are higher than you’d find in an average supermarket, or even at Whole Foods. Peggs doesn’t have to reach far for an analogy — the cost of the first Teslas, two-seaters whose six-figure pricetags proved no obstacle for eager buyers. “Think of it as the roadster of lettuce,” he says. Later, Musk himself will elaborate: “The passion the entrepreneurs put into it makes the food taste 10 times better.”

One selling point of the food is its hyperlocal-ness — grown in the neighborhood where it’s consumed. The Square Roots urban growers often transport their harvest not by truck but subway. While this circumstance does piggyback on the recent mania for crops grown in local terroir, I wonder aloud to Peggs whether food produced in a high-tech container in a dense urban neighborhood, even if it’s a few blocks away, has the same appeal as fresh-off-the-farm crops that are grown on actual farms. In, like, dirt. Can you tell by a grape’s taste if it came from Williamsburg or Crown Heights? I’m having a bit of trouble with that.

Peggs brushes off my objection. Local is local. It’s about transparency and connectedness. “Here’s what I know,” he says. “Consumers are disconnected from the food, disconnected from the people who grow it. We’re putting a farm four stops on the subway from SoHo, where you can know your farmer, meet your farmer. You can hang out and see them harvest. So whether the grower is a no-till soil-based rural farmer or a 23-year or dream-big entrepreneur in a refurbished shipping container, both are on the same side, fighting a common enemy, which is the industrial food system.”

Plants grow in Nabeela Lakhani’s container. (Photo by Natalie Keyssar)

Square Roots is far from the only operation signing on to an incipient boom in indoor agriculture. Indeed, ag tech is now a hot field for investors — maybe not so much that founders can get $100k for just showing up, but big enough that some very influential billionaires have ponied up their dollars. I spoke recently to Matt Barnard, the CEO of a company called Plenty. His investors include funds backed by Eric Schmidt and Jeff Bezos. In its test facility in a South San Francisco warehouse, Plenty is developing techniques that it hopes will bring high-tech agriculture to the shelves of the Walmarts of the world.

In Barnard’s view, indoor agriculture is the only way we will feed the billions of new humans predicted to further crowd our planet. “We have no choice,” he says. “We are out of acreage [of productive land] in many places. In the US, the percentage of imported produce keeps growing.”

Going indoors and using technology, he says, will not only give us more food, but also better food, “beyond organic quality.”

As its name implies, Plenty wants to scale into a huge company that will feed millions. Barnard, who previously built technology infrastructure for the likes of Verizon and Comcast, has a vision of hundreds of distribution hubs — think Amazon or Walmart, near every population center, putting perhaps 85 percent of the world’s population within a short drive of a center. Without having to optimize crops so they can be driven thousands of miles from farm to grocery store, almost all food will be local. “We’ll have food for people, not for trucks,” he says. “This enables us to grow from libraries of seeds that have never been grown commercially, that will taste awesome. These will be the strawberries that beforehand, you only got from your grandmother’s yard.”

As far as that goal goes — better-than-organic crops grown near where you consume them — Plenty is aligned with Square Roots. But Barnard insists that the key element in ag tech will be scale. “Growing food inside is the easy part,” says Barnard. The hardest part is to make food that seven billion people can eat, at prices that fit in everybody’s grocery budget.”

Green Acres? Try Pink Acres! Pictured here, Square Roots farms — and in background is Jay Z’s boyhood home, the Marcy Projects. (Photo by Natalie Keyssar)

Peggs and Musk themselves are interested in scale. They see Square Roots as grass roots — seedlings of a movement that will blossom into a profusion of food entrepreneurs who subscribe to their vision of authentic, healthy chow grown locally.

Earlier this year, Musk dropped by Square Roots to show it off to investors and friends, and then to give a pep talk over lunch to the entrepreneurs. Midway through their year at Square Roots, these urban ag tech pioneers were still enthusiastic as they described their wares. Nabeela Lakhani, who studied nutrition and public health at NYU, described how her distinctive variety of spicy mustard greens had gained a local following. “People lose their minds over this,” she says. Electra Jarvis, who hails from the Bronx, has done a land-office business in selling 2.5-ounce packages of her Asian Greens for $7 each to office workers. (That’s almost $50 a pound.) Maxwell Carmack, describing himself as a lover of nature and technology, packages a variety of his “strong spinach.”

After a tour of the parking lot — the 21st century lower forty — the guests leave and Musk schools the farmer-entrepreneurs as they feast on a spread of sandwiches and salads featuring their recently harvested products. It’s a special treat to hear from the cofounder, as he not only has that famous surname, but also is himself a superstar in the healthy food movement, as well as an entrepreneur who’s done well in his own right. And unlike his brother, who can sometime be dour, Kimbal is a social animal who lights up as he engages people on his favorite subjects.

“Are you making money?” he asks them. Most of them nod affirmatively. Only recently, they have discovered that the “Farmer2Office” program — the one that essentially sells tasty rabbit food for caviar prices — can be a big revenue generator, with 40 corporate customers so far. Peggs guesses that by the end of the year some of the farmers might be generating a $100,000-a-year run rate (the entrepreneurs pay operating expenses and share revenue with the company). But of course, because Square Roots is covering the capital costs of the farms themselves, it’s hard to claim they’re reaping huge profits.

Musk, in cowboy hat, gets back to his roots. Peggs is standing behind him. (Photo by Steven Levy)

“It’s a grind building a business,” Musk tells them. “It’s like chewing glass. If you don’t like a glass sandwich, stop right now.” The young ag tech growers stare at him, their forks frozen in mid-air until he continues. “But you choose your destiny, choose the people around you,” Musk continues.

And then he speaks of the opportunity for Square Roots. This year may only be the first of many cycles where he and Peggs pick 10 new farmers. Within a few years, he will have a small army of real-food entrepreneurs, devoted to disrupting the industry with authentic crops, grown locally. “The real problem is how to reach everybody,” he says. “We’re not going to solve that problem at Square Roots. But there are so many ways you can impact the world when you’re out of here.”

“Whole Foods is stuck in bricks and mortar,” he continues. “We can become the Amazon of real food. If not us, one of you guys. But someone is going to solve that problem.”

The urban farmers look energized. Lunch continues. The salad, fresh from the parking lot, is delicious.

Steven LevyFollow

Editor of Backchannel. Also, I write stuff. Apr 14,2017

Creative Art Direction by Redindhi Studio

Photography by Natalie Keyssar / Steven Levy

Lifelong Farmer Looks East: CEA Farms Wants to Bring Indoor Farm to Eastern Loudoun

Don Virts in his hydroponic greenhouse at CEA Farms in Purcellville. CEA stands for Controlled Environment Agriculture, and Virts says it yields much more produce for much less water, fertilizer, and pesticide. (Renss Greene/Loudoun Now)

Lifelong Farmer Looks East: CEA Farms Wants to Bring Indoor Farm to Eastern Loudoun

2017-04-14 Renss Greene 0 Comment

Don Virts is a new type of farmer.

His family has worked the land in Loudoun for generations, growing beef and produce. But things have changed now. The old ways aren’t sustainable for a small farm anymore, especially with Loudoun’s pricey land values.

In fact, according to the United States Department of Agriculture, farm households bringing in less than $350,000 annually make far more from off-farm income. Although the USDA has very broad definitions for what makes a farm. Perhaps more telling, large-scale farms bringing in more than $1 million a year make up only 2.9 percent of farms, but 42 percent of farm production.

Don Virts saw that his family’s farming business wouldn’t survive without adapting, and in 2015 he started one of the county’s first commercial hydroponic greenhouses. There, he says he gets ten times the yield from his plants, year-round, using 50 percent less fertilizer, 50-80 percent less water, 99 percent less pesticide and fungicide, and zero herbicide. He says if he could afford to build a higher-tech greenhouse, he could do away with pesticide and fungicide altogether.

“I have no desire to be certified organic, because I fully believe that this is better than organic,” Virts said. “Anything grown organically outdoors, you throw a lot of stuff on it to control those problems. It might be approved for organic use, but that doesn’t mean it’s safe.” He said that every year, more and more chemical treatments are approved for organic use.

His greenhouse has a much higher up-front cost than a traditional patch of tomatoes, but after that, costs are lower and production is much higher, on a much smaller footprint.

And he says he can do it in Loudoun’s increasingly urbanized east.

“I had to ask myself, what does Loudoun offer that I can take advantage of?” Virts said. “And what it boils down to is, the same thing that’s putting me out of business is going to turn around to be the thing that’s going to keep me in business.”

By that he means Loudoun’s booming, highly educated, high-income population. He says he can’t keep up with the demand at his CEA Farms Market and Grill in Purcellville, and thinks he can set up another one in the east, bringing the produce closer to the consumer.

“What I’m trying to do is place these things all over the place, and then we have these islands of food production,” Virts said. Instead of the traditional model of produce packed and shipped in from far away, even other hemispheres, Virts wants people eating food picked that morning only a stone’s throw away. So far, it’s working at his greenhouse in Purcellville.

“I built this as a proof of concept, so people would come out there and see this, and see I don’t have a crazy vision,” Virts said. “It’s practical.” He said he knows a landowner in eastern Loudoun who is “very interested” providing him space for a growth facility but hasn’t signed a contract yet.

It’s not just an evolution of how food is grown, but an evolution of the business of growing food.

“This is something one small family farmer cannot do by himself,” Virts said. “I don’t have the resources. I don’t know the restaurant business, I don’t know the renewable energy business.”

The USDA calculated that in 2015, for every dollar spent on food, only 8.6 cents went to the farmer. For every dollar spent in a restaurant, only 3 cents went to the farmer.

Source: USDA Economic Research Service

Virts figures that by growing food close to where it’s eaten, using renewable energy, and cutting out middlemen, he can reclaim most of the money spent on food processing, packaging, transportation, wholesale and retail trading, and energy to bring food to the plate. Those account for 47.6 cents every dollar spent on food.

All that may add up to helping offset the high cost of land in eastern Loudoun. It would give consumers certainty about where their food came from.

His idea would also keep almost all the money spent on food in the local economy, and by cutting down on long-distance transportation and using renewable sources of energy, he can do his part to combat global warming. He has a farmer’s practical, pragmatic outlook on that topic—it has made it more difficult for him, with changing weather patterns and more intense storms.

“I’ve witnessed it on this farm,” Virts said. “When I was kid in high school, we used to take our pickup trucks on this pond [on his farm.] I haven’t been able to go ice skating there in years.”

Along with his other ideas—such as a restaurant with tiered seating overlooking his existing greenhouse—Virts is trying out all kinds of ways to make his family farm work.

“At some point, everybody has to wake up and think about this: Could you do your job, could anybody out there do their job, if they were hungry?” Virts said. “And that’s what it all boils down to, so somebody’s got to figure out that these five acres are worth more money in the long run with a self-sustaining business like this, producing something that everybody needs two or three times a day, than to build townhouses or apartments on it.”

Ultimately, if he can get food production up and running somewhere in eastern Loudoun, it will be another proof-of-concept for the future of small scale agriculture.

“As we get bigger and better, as we build our first one,” Virts said, “there’s going to be some lessons learned there.”

Restaurant Visit: An Innovative Micro Farm at Olmsted in Brooklyn

A buzzy new restaurant in Brooklyn is condensing today’s biggest food trends (farm-to-table, sustainability, no-waste) into a tiny backyard garden. At Olmsted, named for the famous landscape architect who designed nearby Prospect Park, chef Greg Baxtrom (formerly at Per Se and Blue Hill at Stone Barns) and farmer Ian Rothman (the former horticulturist at New York’s Atera restaurant) have cultivated a self-sustaining micro-farm—complete with an aquaponics system in a clawfoot bathtub

Restaurant Visit: An Innovative Micro Farm at Olmsted in Brooklyn

Annie Quigley September 15, 2016

A buzzy new restaurant in Brooklyn is condensing today’s biggest food trends (farm-to-table, sustainability, no-waste) into a tiny backyard garden. At Olmsted, named for the famous landscape architect who designed nearby Prospect Park, chef Greg Baxtrom (formerly at Per Se and Blue Hill at Stone Barns) and farmer Ian Rothman (the former horticulturist at New York’s Atera restaurant) have cultivated a self-sustaining micro-farm—complete with an aquaponics system in a clawfoot bathtub. Plus: The space transforms into an oasis in which to sip garden-fresh cocktails, every dish on the menu is under $24, and a donation is made to nonprofit GrowNYC for every meal eaten. Here, a look inside this clever kitchen garden.

Photography by Evan Sung for Gardenista.

Above: The restaurant, located in the Prospect Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, has a gardening history: The space was once a flower shop.

Above: Baxtrom and Rothman built the backyard micro-farm themselves. The garden is centered on a horseshoe-shaped pine planter surrounded by a perimeter of beds. “We wanted one area that was pretty and would display examples from the menu, and one area that could function as an annual rotation,” says Baxtrom. In the way that an open kitchen might provide a behind-the-scenes view of dinner being cooked, the central bed provides an up-close-and-personal view of dinner being grown. A wood stove in the corner warms the space on cool nights

Above: Gardening in a Brooklyn backyard comes with challenges. To account for shade from buildings and trees, Rothman “identified the shady areas of the garden and chose plant varieties that are better suited for those areas,” including orpine, violets, nettles, ramps, hostas, and pawpaw, says Baxtrom. While there is a small shed for storing tools, the team has to cart soil and supplies through the restaurant to deposit them out back.

Above: The garden provides more than 80 varieties of herbs, vegetables, and other plants for dishes and cocktails on the menu. “We just planted our fall kale rotation,” Baxtrom says. “There is some standard stuff like mint and lemon balm, but also some fun, weird stuff our friends have dropped off for us, like wasabi and white asparagus.” The lemon balm is featured in dishes like a radish top gazpacho, while nasturtium leaves flavor a gin cocktail. (Check back tomorrow for the recipe.)

Above: A pair of quails, mascots of sorts for Olmsted, watch over the garden and provide eggs. A well-worn shovel is a reminder that this is a working farm as well as a restaurant.

Above: To transform the garden into an extension of the restaurant, Rothman and Baxtrom’s father built benches and tables that fit over the planters. The benches are permanently affixed to the beds, but the small tabletops can be removed and used by waitstaff as serving trays. With this space-saving innovation, guests can sit in the garden and enjoy a cocktail—or a cup of tea from the extensive tea menu.

Above: One of the more curious features of the garden is a clawfoot tub-turned-aquaponics system. “We found the tub under the Bronx-Queens Expressway during the buildout,” says Baxtrom. “We wanted the sound of running water in the garden, and somehow the idea evolved to having fish.” The team cleaned out the tub and installed a closed-cycle pump and a filter (“Nothing fancy,” says Baxtrom). The bath now forms a symbiotic and efficient system: The waste from the fish provides manure for water-loving plants, and the plants in turn purify the water.

Above: Watercress and other plants grow alongside crayfish. In another ingenious detail of Olmsted’s closed-loop sustainability system, the team feeds leaves from a tucked-away compost bin to soldier fly larvae which, when grown, are fed to the crayfish.

Above: During dinner, workers dash out to the garden to snip fresh herbs and leaves for the kitchen.

Above: Inside the 50-seat restaurant, a living wall overflows with non-edible plants, and may become an interactive food source in the future. “We have discussed a 2.0 version, like a strawberry or cherry wall,” Baxtrom says, from which guests can pick their own fruit to add to their cocktail.

Above: At night, with lights strung above the space and cushions laid out on the benches, the space transforms from working farm to trendy hangout. As the weather cools, Baxtrom and Rothman are preparing for their first fall and winter at Olmsted: The restaurant will install a hoop house and add heat lamps so diners can enjoy evenings in the garden even after the weather turns cool.

N.B.: For more restaurants with backyard dining, see Outdoor Dining at SF’S Souvla NoPa, Starry String Lights Included.

Vancouver Community Gardens A Gift From Developers Who Get Tax Bre

Vancouver Community Gardens A Gift From Developers Who Get Tax Break

DENISE RYAN

More from Denise Ryan

Published on: April 14, 2017 | Last Updated: April 14, 2017 2:32 PM PDT

Chris Reid is the executive director at Shifting Growth, which sets up community gardens in undeveloped properties throughout the Lower Mainland. Reid is pictured Saturday, April 8, 2017 at the Alma community garden in Vancouver, B.C. JASON PAYNE / PNG

Driving rain couldn’t keep a steady stream of urban gardeners from showing up to claim their plots at a new, temporary community garden at the corner of 10th and Alma in Vancouver last Saturday.

The transformation of a gravel lot on the site of a long-shuttered gas station was spearheaded by Shifting Growth, a Vancouver non-profit that bridges the gap between commercial property owners and urbanites eager to grow their own food.

For a modest buy-in fee of $15, gardeners at one of Shifting Growth’s urban gardens get a 4′ x 3.3′ raised box, already assembled, filled with good soil and access to water. Unlike collective community gardens governed by boards, Shifting Growth gardeners don’t have to deal with the politics of a group or commit hours to site maintenance.

“We take care of all the management. There are no work party requirements, where a lot of the complications come in,” said Chris Reid, executive director of Shifting Growth. “Most people don’t want to be responsible for a non-profit, they just want to grow food, and we let them do that.”

The 100 raised beds at Alma and 10th are on land owned by Landa Global Properties.

“The site has been empty for many years and we thought this would be a great way to give back to the community and do something useful while we go through the development process,” said Kevin Cheung, Landa’s CEO in a statement.

Shifting Growth doesn’t solicit developers because there are enough developers willing to assume the risk and responsibility for the garden projects in exchange for a tax break from the B.C. Assessment Authority. If a vacant lot houses a temporary community garden it will be taxed at a lower rate than on a business site.

Reid said the situation is a win for both the community and developer. “We try to keep it really local, so we put up a notice right by the property, in the hopes that we will get people from the neighbourhood who might live in condos or basement suites, who don’t have another option to grow their own food.”

Young plants ready for planting Saturday, April 8, 2017 at the Alma community garden in Vancouver, BC. JASON PAYNE / PNG

Reid said their land use agreements with corporations range from one to five years. “If we can get one season out of it, it’s a great engagement piece for the community. It’s a great engagement piece for the community.”

Shifting Growth has over 600 garden beds on seven properties from Dunbar to East Vancouver, False Creek to North Vancouver. Vacant residential lots don’t qualify for the same benefit through the B.C. Assessment Authority.

Shifting Growth began with a start-up grant from Vancity Credit Union.

“We had to work against some preconceived notions about community gardens, and the associated risks. We had to prove there was a model that would work,” Reid said.

An unexpected offshoot of the initiative is the success of their pre-fab raised garden boxes, which are set on pallets for drainage, which they now sell through their website shiftinggrowth.com

Reid said Shifting Growth researched and found a German community gardener making use of a hinged shipping industry box that lies flat when not in use. “We import the hinges, buy local untreated cedar and assemble them by hand in Vancouver. It unfolds in about a minute, you fill it with soil and you’re ready to go.”

Beavercreek Veteran Looks To Change Farming Practices

Beavercreek Veteran Looks To Change Farming Practices

Published: April 13, 2017, 6:40 pm

BEAVERCREEK, Ohio (WDTN) – The owner of Oasis Aqua Farm told 2 NEWS he’s trying to make farming more sustainable.

His unconventional farming method started when his mother-in-law wanted to get rid of some fish.

‘She said, hey! Do you guys want fish? And I said well..I work full-time on base, I’ve got two dogs and three kids,” said Kimball Osborne.

Turns out, they got the fish. What does a busy former veteran do with fish?

Kimball decided to try a method of farming he had long been interested in: Aquaponics.

Unlike most farms, the Osborne’s don’t use everyday fertilizer. Their 2,500 square foot facility relies on three key things: heat, dirt and 1,700 fish.

In short, the fish give nutrients to the plants and the plants clean the water for the fish.

“This is our fertilizer factory. We feed them, they feed our plants,” said Mr. Osborne.

The farm is fairly new and once they reach full operation, they expect to feed 100 people per week.

It’s Mr. Osborne’s childhood love of gardening that made him pursue Aquaponics.

“I’ve always done it. I’ve always had a garden. I’m also a cost analyst, I had millions of questions,” said Osborne.

After countless phone calls and classes, Osborne is ready and so is his community.

“Everyone has been extremely supportive. In fact one lady bought a share and said she has a garden, but just wanted to support us.”

If you would like to learn more about Oasis Aqua Farm, click here.

A Brooklyn Rooftop, Condo Owners Will Be Able To Sign Up For Plots To Harvest Edible Crops

A Brooklyn Rooftop, Condo Owners Will Be Able To Sign Up For Plots To Harvest Edible Crops

Wednesday, April 12, 2017 17:25

Under construction.

Rooftop view of 550 Vanderbilt in Brooklyn, where tenants will be able to grow crops. Photo: Peter J. Smith For The Wall Street Journal

Do-it-yourself farmers who can afford condos priced at an average of $1,500 a square foot, with one-bedroom units starting at $890,000 and two-bedrooms at $1.495 million.

By Josh Barbanel - Wall St Journal

April 5, 2017

Excerpts:

On a large south-facing terrace on the eighth floor of 550 Vanderbilt Ave., an 18-story brick and concrete building near the Barclays Center in downtown Brooklyn, crews are erecting three large metal boxes and filling them with soil suitable for high-altitude farming.

Condo owners will be able to sign up for a small plot to grow their own vegetables there, alongside Ian Rothman, a farmer and co-owner of Olmsted, a trendy farm-to-table restaurant a few blocks away.

Mr. Rothman has been promised a large subdivision of the plots, and is planning an initial crop of hot peppers for the restaurant’s home-made aji dulce sauce served with oysters. The restaurant is named for Frederick Law Olmsted, the landscape architect who designed the nearby Prospect Park.

“We plan to develop a substantial amount of our space to peppers,” Mr. Rothman said. It will augment the restaurant’s modest rear yard, where he grows garlic, radishes, herbs and edible flowers.

550 Vanderbilt is providing a terrace for do-it-yourself farmers who can afford condos priced at an average of $1,500 a square foot, with one-bedroom units starting at $890,000 and two-bedrooms at $1.495 million. The building is being developed by a joint venture between Greenland USA, a subsidiary of Shanghai-based Greenland Group Co., and Forest City Ratner Cos., a subsidiary of Forest City Realty Trust Inc.

Condo owners will be able to sign up each season for plots of at least 7 feet by 10 feet in the 1,600 square-foot farm, enough to harvest a significant edible crop, said Ashley Cotton, executive vice president for external affairs at Forest City Ratner Cos. The largest farm bed will be about 39 feet by 21 feet and will be divided by plank walkways.

Mr. Rothman founded a boutique farm in Massachusetts and then raised herbs, vegetables and edible flowers in a subterranean garden beneath Atera, a Tribeca tasting-menu restaurant that charges $275 per person, not including beverages.

The idea for the 550 Vanderbilt Ave. vegetable garden came from COOKFOX Architects, which designed the building. The firm follows a principle it calls “biophilic design,” or the creation of spaces that promote human well being by enhancing the connection between people and nature, said architect Brandon Specketer, who worked on the building.

Shanghai is Planning a Massive 100-Hectare Vertical Farm to Feed 24 Million People

Shanghai is Planning a Massive 100-Hectare Vertical Farm to Feed 24 Million People

International architecture firm Sasaki just unveiled plans for a spectacular 100-hectare urban farm set amidst the soaring skyscapers of Shanghai. The project is a mega farming laboratory that will meet the food needs of almost 24 million people while serving as a center for innovation, interaction, and education within the world of urban agriculture.

The Sunqiao Urban Agricultural District is composed of vertical farms that fit in nicely between the city’s many towers, adding a welcomed green counterpart to the shiny metal and glass cityscape. In a city like Shanghai, where real estate prices make vertical building more affordable, the urban farm layout counts on a number of separate buildings that will have various growing platforms such as algae farms, floating greenhouses, vertical walls and even seed libraries. The project incorporates several different farming methods including hydroponic and aquaponic systems.

The masterplan was designed to provide large-scale food production as well as education. Sunqiao will focus on sustainable agriculture as a key component for urban growth. “This approach actively supports a more sustainable food network while increasing the quality of life in the city through a community program of restaurants, markets, a culinary academy, and pick-your-own experience” explained Sasaki. “As cities continue to expand, we must continue to challenge the dichotomy between what is urban and what is rural. Sunqiao seeks to prove that you can have your kale and eat it too.”

Visitors to the complex will be able to tour the interactive greenhouses, a science museum, and aquaponics systems, all of which are geared to showcase the various technologies which can help keep a large urban population healthy. Additionally, there will be family-friendly events and workshops to educate children about various agricultural techniques.

Via Archdaily

Upping The Ante on Urban Agriculture Research

Upping The Ante on Urban Agriculture Research

In addition to his work studying recycled nutrients in the soil of the community garden, professor Chip Small studies the same phenomenon in hydroponics, where the waste from fish is used to feed aquatic plants. (Photo by Mike Ekern '02)

Jordan Osterman '11

April 5, 2017

It’s easy to assume everything is ready to continue smoothly in the growing field of urban agriculture: Urban home and community gardens pop up more and more, and the evidence of sustainability and social benefits continues to grow. More of a good thing is a good thing, right?

Well, hold that thought. As is often the case with the complexities of modern life, there’s a bit more to the picture. Freshly armed with a $500,000 grant over five years from the National Science Foundation, St. Thomas biology faculty Chip Small and Adam Kay, and their students, are primed to contribute some much-needed science: They will be studying what effects recycled nutrients have in the soils of community gardens, which could greatly help shape the future of how urban ecosystems handle food.

“The main focal point of the grant is on the use of nutrients and how to recycle them efficiently. That’s such a general issue for an expanding population,” Kay said. “We know the stats of how 40-some percent of food is wasted in the agriculture system, so thinking about how the human civilization collectively can operate more efficiently, we’re going to need that moving forward.”

Small, who secured the funding as an early career grant, has been studying nutrient recycling in different ecosystems since his Ph.D. research and recently has shifted his lens to urban ecosystems.

“I’ve been asking questions about how efficiently we can recycle nutrients from food waste into new food through composting, coupled with urban agriculture,” Small said. “Something like nearly half the food imported into cities ends up as waste, and we compost maybe 5 percent of that waste. Theoretically that could be scaled up and provide lots of nutrients for urban agriculture.”

Of course, scaling anything up means increasing the amount of everything in play and, when it comes to growing food, that means increasing the amount of phosphorus.

“There’s sort of a nutrient mismatch between compost and what crops need. Compost, food waste, manure tend to have a lot of phosphorus relative to nitrogen,” Small said. “What we’re seeing is a lot of urban gardens that … are leeching out phosphorus. We have laws in Minnesota that you can’t just put phosphorus fertilizer on your yard because we’re concerned about water pollution and phosphorus going into lakes. But, you can put as much compost as you want in your garden and you might have the same effect. Nobody has really looked at that. That’s the research question.”

Finding their niche

Over the past six years Kay and his students have worked to develop a physical infrastructure that will be more crucial than ever for this expanding research: St. Thomas’ on-campus sustainability garden and two community gardens in St. Paul have been – and will continue to be – fertile grounds for experiments.

“There have been many students who have … worked long days, going above and beyond to establish these sites on campus, at community centers, and making everything run professionally, building up goodwill with neighbors, community members, government officials, local organizations,” Kay said. “Putting themselves out to make this work, and now it feels like the gamble paid off.”

Having such a strong base of gardens to experiment with is a rare resource for a university, which definitely helped secure this new funding, Small said. Another aspect was how under-researched urban agriculture has been to this point, meaning Small, Kay and their students are wading into relatively uncharted waters.

“This is kind of outside-the-box stuff we’re doing; it’s a niche that I think is really good for us,” Small said. “Obviously land grant universities are good at doing big-scale agriculture stuff, but urban agriculture is a totally different thing, different scale, different management processes. There’s gotten to be some good social science surrounding this … but there just has not been much of this [kind of] science at all. There are some interesting science questions here.”

Small said they have worked with leaders in Minneapolis and St. Paul, including city councils, to better understand what information could be most beneficial for shaping how food is treated within their cities.

“We’ve gotten a pretty good feel for what some of the relevant questions that cities are asking,” he said. “The information we can provide with this research will be very applicable and we’ll make it readily available. … We want to make this as accessible as possible for the whole community.”

Watering St. Thomas’ scholarly model

Another aspect of the grant Small said St. Thomas was suited for was an emphasis on integrating students’ research with teaching. That “works perfectly here,” Small said. “I’ve already got research incorporated into the courses I teach and we can keep building off that.”

“This award not only recognizes the importance of the research itself, but is also a testament to our commitment to the teacher-scholar model,” said Biology Department chair Jayna Ditty. “This award reflects how much we as a community value the integration of education and research, and I am excited to see what Chip, Adam and their students are able to accomplish in the next five years.”

Senior Katherine Connelly – who’s taking Small’s Urban Ecosystem Ecology course and will stay on this summer to help with research – said her experience already has expanded her ideas about agriculture after growing up on a large family farm in Burnsville, Minnesota.

“Cities depend on rural areas for their food, but now we see that cities are constantly expanding and are only going to get bigger. With the increasing size you have more need for food in these areas, so urban agriculture is a way for cities to have more food independence,” she said. “Urban agriculture won’t necessarily be able to feed everyone, but it has a lot of other benefits – economic, community benefits – that we can potentially take more advantage of.”

With more and more students like Connelly having the opportunity to contribute thanks to the NSF’s additional funding, there’s increasing optimism about the contributions they will make toward the community’s common good.

“The thing that’s most gratifying is that it did seem to emerge from the commitment to making the world a better place. It wasn’t just an abstract, scientific pursuit … it was people realizing there were broader social benefits that come out of this,” Kay said. “That’s a real inspiration and something I hope people can see, how there’s ways of having people have their scholarship be connected to our mission and broader goals, and still be viable in your field.

“We use the food we produce for farmers markets, for generating enthusiasm about nutrition on campus and for all the work we do in communities like with Brightside Produce … the work at the community centers where students are ambassadors for the projects, working with small children. All these projects are possible because of the nature of food production in these settings,” Kay added. “This resonates with a lot of people.”