Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

What Do Investors Need To Know About The Future of LED Grow Light Technology?

NOVEMBER 16, 2018 PATRICK FLYNN

Editor’s Note: Patrick Flynn created Urbanvine.co in 2016 to help urban dwellers learn how to start urban farming without any previous experience. As the site grew, he discovered that “urban farming” was actually a general term that can include a wide variety of concepts, including grow lights and hydroponics, topics which the site now covers in depth.

The horticultural lighting market is growing, and growing rapidly. According to a September press release from Report Linker, a market research firm specializing in agribusiness, the horticultural lighting market is estimated grow from a $2.43 billion market this year to $6.21 billion in 2023.

One of the key factors driving current market sector growth is increased development of LED grow light technology. LEDs (light emitting diodes) were first developed in the 1950s as a smaller and longer-lasting source of light compared to the traditional incandescent light bulb invented by Thomas Edison in 1879.

LEDs last longer, give off less heat, and are more efficient converting energy to light compared to other types of lights, all features that can result in higher yields and profits for indoor growers.

But until recently, LEDs were only used to grow plants indoors experimentally, largely because the cost was still too high for commercial businesses. Many commercial growers still use HID (High Intensity Discharge) lights such as High Pressure Sodium, Metal Halide, and Ceramic Metal Halide; all lights that have a high power output but are less durable than LED lights, generate far more heat, and have less customizable light spectra.

Today, LEDs are fast becoming the dominant horticultural lighting solution. This is due primarily to the one-million fold decrease in fabrication cost of semiconductor chips used to make LED lights since 1954.

For investors more familiar with field-based agriculture, it can certainly be a minefield to know where LED lighting technology for horticulture is going in the future. Although it is no longer the “early days” of LED technology development, current trends are still shaping the future of LED technology.

So what does the intelligent agtech investor need to know about the current state and future of LED grow light technology?

I interviewed Jeff Mastin, director of R&D at Total Grow LED Lighting, to discuss what the future of LED grow light technology for agriculture looks like, and how investors can use current trends to their advantage in the future.

What is your background – how did you get involved in grow light technology at Total Grow?

The company behind TotalGrow is called Venntis Technologies. Venntis has, and still does, specialize in integrating touch-sensing semiconductor technologies into applications.

Most people don’t realize LEDs are semiconductors; you can also use them for touch-sensing technologies, so there’s a strong bridge to agricultural LED technology.

Some of the biggest technical challenges in utilizing LEDs effectively for agriculture include LED glaring, shadowing and color separation.

We have used our expertise in touch-sensing LEDs to expand into horticultural LEDs, and we have developed technology that addresses the above challenges better, giving better control over the spectrum that the LED makes and the directional output of the light in a way that a standard LED by itself can’t do.

My personal background is in biology. When TotalGrow started exploring the horticultural world, that’s where being a biologist was a natural fit to take a lead on the science and the research side of the development process for the product; that was about 7 years ago now.

If you were going to distill your technical focus into trends that you’re seeing in the horticultural lighting space, what are the main trends to keep an eye on?

The horticultural lighting industry is really becoming revolutionized because of LEDs. Less than 10 years ago, LEDs in the horticultural world were mainly a research tool and a novelty.

In the past, they were not efficient enough and they were definitely not affordable enough yet to really consider them an economical general commercial light source.

But that is very quickly changing. The efficiencies are going up and prices down and they are really right now hitting the tipping point where for a lot of applications, but definitely not all applications, the LED world is starting to take over horticulture and indoor agriculture.

How do you view the translation of those trends into actionable points? For investors or technology developers in the agriculture technology space, how do they make sure that the LED light technology they are investing in isn’t going to be obsolete in a year or two?

With LEDs, the key question is still cost-efficiency, and there’s only so far the technology can improve.

Why? There are physical limitations. You can’t make a 100% efficient product that turns every bit of electricity into photons of light. At this point, the efficiency level of the top of line LEDs are up over 50%.

Can we ever get up to 70 or 80%? Probably not any time soon with an end-product, not one that’s going to be affordable and economical generally speaking.

So to answer your question, it’s not a category where you’re going to say, “well this is obsolete, I can get something three times better now.” The performance improvements will be more marginal in the future.

Ten years from now the cost will be cheaper. But that again doesn’t make current LED technologies obsolete. In terms of that fear, I don’t think people have to worry about current LED light technologies becoming obsolete.

In a large commercial vertical farming set up, what is the ballpark cost of horticultural LEDs currently?

To give just an order of magnitude sort of number, you’re probably going to be someplace in the $30 per square foot number for lights for a large facility. It can be half that or it can be double that.

That’s just talking within the realm of common vertical farming plants like greens and herbs, or other plants similar in size and lighting needs.

If you start talking about tomatoes or medicinal plants, then the ability to use higher light levels and have the plants make good use of it skyrockets. You can go four times higher with some of those other plants, and for good reason.

What type of horticultural lighting applications are LEDs still not the best solution for now and in the foreseeable future?

There are at least 3 areas where LEDs still may not make sense now and in the near future.

First, if the LED lights are not used often enough. The more hours per year the lights are used, the more quickly they return on their investment from power savings and reduced maintenance. Some applications only need a few weeks of lighting per year, which makes a cheaper solution appropriate.

Second, in some greenhouse applications, LED’s may not be the best choice for some time to come. Cheaper lights like high-pressure sodium have more of a role in greenhouses where hours of use are less and higher hang heights are possible. (Many greenhouses will still benefit strongly from LEDs, but the economics and other considerations make it important to consider both options in greenhouses.)

Lastly, some plants are not the best in vertical farming styles of growing where LEDs have their most drastic advantages. At least at this point it is not common to attempt to grow larger fruiting plants like tomatoes or cucumbers totally indoors, though when attempted that is still more practical with LEDs than legacy lights.

Thanks Jeff!

To learn more about Total Grow, visit www.totalgrowlight.com

The Artist Creating Urban Farms To Feed Philadelphia

With fresh fruit and vegetables hard to come by in some of the city’s soup kitchens, Meei Ling Ng plants gardens to provide hyper-local produce to the homeless.

2018

Not many churches can boast their own Garden of Eden, but South Philadelphia’s historic Union Baptist Church (UBC) can. When Loretta Lewis and other veteran congregants of UBC opened a soup kitchen 20 years ago, they made a solemn pledge: “We just vowed that we’re not going feed people anything that we wouldn’t eat or feed our families,” she says. “The people who come are used to eating substandard food, but here they have never had substandard food.”

The soup kitchen volunteers have always prepared for the weekly Friday luncheon by shopping for and cooking food in an industrial kitchen in the church’s basement, adjacent to a dining room with cloth-covered tables, where people from nearby shelters are welcome to enjoy a free, nutritious meal.

And for the past year, sourcing fresh vegetables—often a big challenge for the church—has been easy. The soup kitchen’s pantry is now supplemented by hyper-local produce, harvested the same day from a new garden in a previously underused plot next door to the church.

Meei Ling Ng, an artist and urban grower who lives nearby, began a collaboration with the church a year and a half ago to develop what they’ve jointly called the UBC Garden of Eden. “I want to promote ‘grow food where you live,’” Ng says. “That’s always my project title, everywhere. And ‘provide fresh, healthy food to the needy, to the homeless.’ It benefits the rest of the community, too, through educating how to grow.”

Meei Ling Ng visiting with Loretta Lewis at the UBC Garden of Eden. (Photo courtesy Karen Chernick)

In essence, Ng and UBC have cooperated on of a farm-to-table soup kitchen that supports the church’s need for (often costly) produce, while simultaneously involving the community by inviting them to help tend the garden two days a week. “We were pretty much supporting the soup kitchen on our own,” says Lewis, “but with Meei Ling, even early in the [garden’s first] year, we had salad.”

Ng planted an unusual variety of crops that include black heirloom tomatoes, rainbow chard, summer squash, purple cauliflower, Asian pears, and almonds, all cultivated in raised beds and in an orchard along the church’s perimeter. In a way, she has replicated the model of her childhood home on a five-acre orchid farm in Singapore, where her family self-sustained all of its produce needs.

“We had rows and rows of vegetables and fruit trees everywhere,” Ng recalls. “I grew up in that kind of environment. Everything we picked we ate fresh.” Having lived in Philadelphia for more than two decades, Ng is undeterred by her current home’s urban density in finding places to grow food.

As a working artist, Ng considers the UBC Garden of Eden to be an extension of her multimedia installation sculptures, many of which are food- and farm-themed. Some of her past works in Philadelphia include a musical garden at SpArc Services and the Deep Roots series of installations at two of the city’s urban farms.

The UBC Garden of Eden is the second of her spontaneously developed hunger-relief urban farms; the first such project was at Sunday Breakfast Rescue Mission, Philadelphia’s largest homeless emergency shelter. There, a string of raised beds along the edge of the mission’s parking lot have provided the high-volume kitchen with fresh vegetables (such as tomatoes, salad greens, and fresh herbs) since 2015, as well as farming instruction for those overcoming homelessness.

The Sunday Breakfast Mission garden. Photo © Sang Cun

“Fresh produce is extremely hard to come by,” says Rosalyn Forbes, the director of development at Sunday Breakfast Rescue Mission. “We rely heavily on donated nonperishable food items, which means that much of the fruits and vegetables we serve are canned. The Sunday Breakfast Farm provides fresh produce that can then be served in our kitchen.”

Salads are composed of freshly harvested greens; the herb garden is thoughtfully situated outside the kitchen door so that it is easy to reach while cooking. “It has elevated the quality of the food being served at the Mission,” Forbes continues. “Too often, those experiencing homelessness also suffer from health problems related to a poor diet.”

Solving the Problem of Scale

Sourcing fresh produce—and staying within budget—is a challenge for many soup kitchens. Individual donations of perishable items are rare, so some organizations choose to work with hunger-relief nonprofits that have the logistical capability to glean fruit and vegetable gifts directly from local farmers. The Philadelphia Orchard Project, which contributed fig, almond, and Asian pear trees to the UBC Garden of Eden this year, has a fruit gleaning program. Philabundance, another local nonprofit, is known by Philadelphia-area farmers as a way to keep excess or less cosmetically attractive produce from going to waste.

Distribution of this donated produce requires complex transportation, however, and so soup kitchens must often meet certain volume criteria in order to receive deliveries. Philabundance, for example, requires that its soup-kitchen member agencies serve at least 500 monthly meals in order to qualify. For smaller-scale operations that don’t reach that number, such as UBC’s soup kitchen (which has fed around 70-80 people per week in previous years and feeds between 20-30 each week now), this usually means they have to purchase produce themselves or rely on non-perishable items.

“Produce is hard to come by [for] smaller operations, and [direct] donations of produce [by farmers] could have a major impact,” says Scott Smith, director of food acquisition at Philabundance.

By growing the produce themselves, Ng and the UBC soup kitchen volunteers are slowly sidestepping the need to seek produce donations or purchase fruits and vegetables for the program. Phil Forsyth, executive director of Philadelphia Orchard Project, praised this solution, saying, “Of course, another approach is for soup kitchens to plant their own gardens and orchards to supply themselves with the most fresh, local produce possible.”

Planter beds in the UBC Garden of Eden. (Photo courtesy Karen Chernick)

Even for larger organizations such as Sunday Breakfast Rescue Mission, which serves over 400 meals daily and qualifies for delivery from organizations such as Philabundance, the parking-lot farm developed by Ng serves an important function. “There never seems to be enough donated fresh produce to keep up with the demand,” notes Forbes, “which is why we decided to think outside the box and grow it ourselves.”

As an added benefit, Ng’s farms engage their surrounding urban communities and teach city dwellers that even figs can grow on a city block. An herb garden can flourish in a parking lot, and heirloom tomatoes can thrive in a raised bed built out of salvage materials from the demolition of a nearby growhouse.

The care Ng takes in nurturing the crops at UBC Garden of Eden matches the motivation that the church’s soup kitchen volunteers have for serving food they would feed their own families. The symbiosis has been apparent since Ng’s first harvest last summer. “I was so happy and delighted to see a green area of the plate,” Ng says. “I want to share that experience of fresh produce with people. It tastes different, because it’s so fresh.”

Top photo: Meei Ling Ng in the Sunday Breakfast Rescue Mission Farm. (Photo © Sang Cun)

iGrow News

iGrow News

iGrow News Is an online digital platform which allows individuals, companies, universities, and researchers of the urban indoor farming industry to connect, ask questions and network with other industry individuals in their field, in order to gain knowledge as well as spread knowledge.

To research topics that may be of interest, scan the industry activity and to get the latest in industry news, check out what your fellow urban farmers are doing by keeping up with the activity on iGrow News.

We have a product that allows you to connect worldwide and facilitate business like never before in the history of urban farming.

American Association of Urban & Indoor Farmers

Who Are We?

The Urban & Indoor farming movement is expanding by the minute. For this movement to live up to its potential, it needs the tools to grow and thrive. That’s where we come in.

For our community to thrive and reach our fullest potential together as professionals and consumers in a unique movement, we need to work together. We need to connect, build relationships, and create a better business environment that benefits everyone.

Connect with us on iGrow News, Join our mailing list, so that you will be notified when The American Association of Urban & Indoor Farmers will be accepting applications for membership.

We realized early on at iGrow News that we wouldn’t just be a platform for the produce industry; Just as professionals in the produce business, consumers of produce also need a reliable and informative resource in order to keep informed of the latest innovations.

We are currently developing the consumer portion of our site.

Soon you will be able to create a profile and interact with not only like-minded produce consumers but also professionals in the industry.

iGrow News is developing iGrow Funding to assist the indoor farming community with their financing requirements.

Infarm Expands Its ‘In-Store Farming’ To Paris

Steve O'Hear@sohear / November 8, 2018

Infarm, the Berlin-based startup that has developed vertical farming tech for grocery stores, restaurants and local distribution centres to bring fresh and artisan produce much closer to the consumer, is expanding to Paris.

Once again, the company is partnering with Metro in a move that will see Infarm’s “in-store farming” platform installed in the retailer’s flagship store in the French capital city later this month. The 80 metre square “vertical farm” will produce approximately 4 tonnes of premium quality herbs, leafy greens, and microgreens annually, and means that Metro will become completely self-sufficient in its herb production with its own in-store farm.

Founded in 2013 by Osnat Michaeli, and brothers Erez and Guy Galonska, Infarm has developed an “indoor vertical farming” system capable of growing anything from herbs, lettuce and other vegetables, and even fruit. It then places these modular farms in a variety of customer-facing city locations, such as grocery stores, restaurants, shopping malls, and schools, thus enabling the end-customer to actually pick the produce themselves.

The distributed system is designed to be infinitely scalable — you simply add more modules, space permitting — whilst the whole thing is cloud-based, meaning the farms can be monitored and controlled from Infarm’s central control centre. It’s data-driven: a combination of IoT, Big Data and cloud analytics akin to “Farming-as-a-Service”.

The idea isn’t just to produce fresher and better tasting produce and re-introduce forgotten or rare varieties, but to disrupt the supply chain as a whole, which remains inefficient and produces a lot of waste.

“Many before have tried to solve the deficiencies in the current supply chain, we wanted to redesign the entire chain from start to finish; Instead of building large-scale farms outside of the city, optimising on a specific yield and then distributing the produce, we decided it would be more effective to distribute the farms themselves and farm directly where people live and eat,” explains Erez Galonska, co-founder and CEO of Infarm, in a statement.

Meanwhile, the move into France follows $25 million in Series A funding raised by Infarm at the start of the year and is part of an expansion plan that has already seen one hundred farms powered by the Infarm platform launch. Other recent installations include Edeka locations in Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, Stuttgart, and Hannover. Further expansion into Zurich, Amsterdam, and London is said to be planned over the coming months.

“One thousand in-store farms are being rolled out in Germany alone,” adds Infarm’s Osnat Michaeli. “We are expanding to other European markets each and every day, partnering with leading supermarket chains and planning our North America expansion program for 2019. Recognising the requirements of our customers we have recently launched a new product; DC farm – a ‘Seed to Package’ production facility tailored to the needs of retail chains’ distribution centres. We’ve just installed our very first ‘DC farm’ in EDEKA’s distribution center”.

Indoor Neon-Lit Mushroom Farms Are New York's Hottest New Food Trend

Pink oyster mushrooms grown in a ‘mini farm’ unit. Photograph: Hannah Shufro

Written by: Laura Pitcher

Diners at the Bunker, a Vietnamese restaurant in Brooklyn, may not realise that the mushrooms in their bánh mì were grown in a blue-tinted, spaceship-looking “mini farm” underneath their seats. But it’s just one of a growing number of plug-in fungi farms mushrooming in New York City.

Smallhold, the company that created the idea, grows around 100 pounds of various mushroom types a week, then distributes them three-quarters grown to climate-controlled, do-it-yourself mini “farms” around the city. The mushrooms finish growing within the automated units, while a remote technician adjusts humidity, airflow and temperature, offering chefs on-the-spot, fresh and self-replenishing batches of a food item that has a short shelf-life.

The units could also work for perishables such as lettuce and herbs but the company is currently focused on catching the rising fashion for exotic mushrooms. “Mushrooms are amazing. Mushrooms are the future,” co-founder Andrew Carter gushed to the Guardian. “When you usually find them, they tend to be really gross looking on the shelves because they’ve been sitting in trucks. This way, we can give them [the customers] a brand-new experience with mushrooms.”

They currently sell nine mushroom varieties, including oyster, lion’s mane, shiitake and pioppino.

Smallhold ‘farm’ unit at a Whole Foods store containing mushrooms. Photograph: Hannah Shufro

Smallhold has been distributing their farms through partner restaurants and markets, including Manhattan’s Mission Chinese restaurant, Kimchee Market in Greenpoint and a Whole Foods store in Bridgewater, New Jersey.

Smallhold farms also happen to look very pretty, with weird mushroom formations glowing under nightclub-style lighting. Danny Bowien, the chef and owner of Mission Chinese Food, told Vogue in an interview that many of his customers think the units in his restaurant are art. The launch of the first unit in the Whole Foods store saw a similar reaction. Confused shoppers crowded four-deep around the mushrooms.

Blue oyster mushrooms. Photograph: Andrew Carter

But Carter and his co-founder and college friend Adam DeMartino insist it’s more than just an aesthetic trend. They argue the cultivation process is more sustainable than traditional mushroom farms, using about 96% less water, creating 40 times the output per square foot and less food waste.

The organic material the mushrooms grow in is also sustainable, made from recycled materials such as sawdust, coffee grounds and wheat berries.

Setting up a mini-farm is not cheap, prices start at $3,500, and there are cheaper generic indoor grow units available. Home Depot currently sells a small cardboard miniature organic mushroom farm for $39.99 per box.

The pair acknowledge they may soon face competition, but for now they appear to be something of a status symbol. As one local blogger put it, it’s like they’ve created the “vegan version of the lobster tank”.

This article contains affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if a reader clicks through and makes a purchase. All our journalism is independent and is in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative.

The links are powered by Skimlinks. By clicking on an affiliate link, you accept that Skimlinks cookies will be set. More information.

Urban Crop Solutions Offers A Glowing And Growing Global Future For Indoor Farming

A start-up that engineers and builds fully automated indoor vertical farms inside shipping containers and buildings.

by S. Virani

25 September 2018

“Imagine yourself standing inside a climate-controlled, high-ceiling warehouse. In front of you stands a tower with 8 irrigated levels, on each of which lettuces, herbs, micro greens, and baby greens grow under LED lights. Robotics move trays with young plants from outside this grow room into the right position in the grow tower, while on the other end fully grown crops are taken out, ready to be harvested. Can you see it? You are standing in Urban Crop Solutions' Plant Factory — the state-of-the-art in indoor vertical farming technology. A highly engineered manufacturing plant producing not goods, but crops.” — Urban Crop Solutions.

Meet Urban Crop Solutions: A start-up that engineers and builds fully automated indoor vertical farms inside shipping containers and buildings. They also provide clients that have bought a system with carefully selected and tested seeds, substrates, nutrients and comprehensive software grow recipes. The result: year-round production of fresh and healthy crops.

The start-up’s goal is to create an optimum environment for plants to grow, with the right combination of climate, lighting and nutrients throughout their growth cycle.

From left, Frederic Bulcaen, co-founder and chairman at Urban Crop Solutions, with Brecht Stubbe, global sales director and Maarten Vandecruys, co-founder and CEO with at European FoodNexus Award Ceremony

Headquartered in Belgium, with regional offices in Miami (USA) and Osaka (Japan) as well as a network of sales agents in various territories, Urban Crop Solutions will take part in the World Agri-Tech Innovation Summit to be held from October 16-17 in London, selected as one of the 13 start-ups to present their innovative solutions.

Produce Business UK sat down with Brecht Stubbe, global sales director of Urban Crop Solutions, to understand the technology that the start-up has developed, as well the growth of the vertical farming market in general, challenges that farmers face now and will face in the future, and Urban Crop Solutions’ formulas to combat food shortage in the future.

How did the Urban Crop Solution concept come about?

By 2050, more than 70 per cent of all people will live in cities. The population will grow from 2.5 billion to over 9.8 billion, leading to a need to produce 70 per cent more food. In 2012, 80 per cent of the land suitable for agriculture was already in use. Due to these facts, it was safe to say that something needed to change.

That is when our co-founder (Maarten Vandecruys) started thinking: “What if we could use technology to grow any plant, year-round and independent of local climate? What if we could do this using 95 per cent less fresh water? What if we could do this using zero pesticides and herbicides?” Together with Frédéric Bulcaen, the other co-founder who acted as a business angel, they set out to explore this further.

With the above goals in mind, modular solutions were developed at Urban Crop Solutions: A fully controlled and automated resolution that can be placed anywhere and which can grow any plant. Imagine a closed box or warehouse with crisp white walls in which plants are grown using LED lights, as well as without soil.

In lieu of the Agri-Innovation Summit, where you will present alongside a dozen or so other start-ups, what is it about your technology that stands out and set up apart? Essentially what is your unique selling point?

Urban Crop Solutions has a total turnkey solution, as well the latest technology in terms of indoor farming systems. A big difference with other competitors is the fact that we have plant scientists that develop recipes for more than 180 crop varieties. We also offer all the consumables — seeds, substrates, nutrients — to help you grow your crops.

Finally, we have experience all over the globe, from Belgium to Japan to Miami.

So when we look at our unique selling propositions, these would be the consistent high quality of produce combined with our biological know-how of how to grow them, as well as the use of automation to bring down labour costs.

Let’s talk about your clientele and the sorts of industries that you have worked with? Furthermore, would you say there has been a growth in demand for this over the years?

A first category of clients are the entrepreneurs, people who see the opportunity this technology offers and plan to start from scratch. For example, those who want to build a produce brand growing vertically and indoors.

Another category are R&D institutions and corporate departments as well as crop science companies that use our technology to conduct relevant research while being able to manage all variables precisely to their needs.

A third important category is the existing vertical farmers who are looking for a high-quality, third-party solution provider to help them scale.

We would also include the category of existing traditional farmers that are looking to capture the new market this technology offers by complementing their existing production methods. For example, open-field and greenhouse farming.

Do you see other start-ups competing in this space?

Not really. There are a lot of vertical farmers focused on growing and integrating technology themselves. However, they are not any qualitative total solution providers like Urban Crop Solutions, that have the ability to design and build a tailored, fully automated efficient solution the world over.

We just did a piece about the new Emirates Airlines vertical farm. It provides an example of how other industries can apply and utilize the vertical farm. What are your thoughts on that?

This is a good example of disruptive new business opportunities and vertical integration into supply chains. Zooming out, the broader definition of this case can be defined as food catering companies (a subcategory of food processing companies) integrating produce farming into their business. The technology allows them to capture an additional margin by adding the value themselves as opposed to buying the produce from a third party and enables them to perform just-in-time production with reductions in waste and certainty of ability to deliver.

You have various solutions on your website: The Farmflex Container, The Farmpro Container? The Plant Factory. What are the main differences between all of them?

We have two different product categories:

Off-the-shelve product

This includes our FarmPro & FarmFlex container. These are mainly used as a first stepping stone/proof of concept for companies that would like to grow commercially or conduct research on a larger scale in the future.

FarmPro container: The Urban Crop Solutions FarmPro is a 40-foot, fully automated freight container with a state-of-the-art leafy green growing system. This system gives a four-layer growing solution. Its design is primarily focused on growing lettuce and individual herbs.

FarmFlex container: This system has a state-of-the-art leafy green growing rack setup. It gives a fully automated, four-layer growing solution with maximum flexibility as to what you can grow. For this reason, educational and research institutions have the highest demand for this product, as it allows growth of almost anything: lettuce, herbs, micro greens, baby greens and more.

Then we have custom-made large-scale solutions:

PlantFactory: Our Urban Crop Solutions PlantFactory allows you to grow in any available space, whether it is a basement or a warehouse. This way, you can produce leafy greens year-round on an industrial scale or set up complex large-scale R&D infrastructure.

In an Urban Crop Solutions PlantFactory, everything is designed and engineered according to the available space, as well as to the customers’ needs. For example, the cultivation area, our innovative LED growing technology, ingenious irrigation systems and climate control.

In terms of industries, what industries do you work with, and what would you say are the industries most relevant for now in 2018?

Agricultural food production and crop science research are the most relevant industries for 2018 based on the demand they produce for us.

As a B2B publication focused on produce, we are interested in how vertical farming truly can affect the industry as a whole. What are some predictions you might have about the effect of vertical farming on produce? Are there particular fruits or vegetables that will thrive in this environment and produce higher yields?

There exists a distinction between what we can grow from a technical standpoint (almost everything – even strawberries, cucumbers, tomatoes, peppers, etc.) Then, however, there is the commercial standpoint. The latter is more limited because obviously one needs a positive cash flow. The capital-investment cost and substantial operational costs (e.g. electricity) require that one selects a crop that has a short grow cycle, high density and harvests the full biomass created.

As a result, the current commercially viable food production crops are the leafy greens such as lettuce, herbs, baby greens and micro greens.

Just how good, just how efficient are these farms?

The farms can be tailored to include carefully selected and tested seeds, substrates, nutrients and a comprehensive software tool automatically providing the plants with the right combination of climate, lighting and nutrients throughout their growth cycle. Our solution leads to higher yields, higher nutritional value, food safety and security, higher water efficiency. This can actually be up to 95 per cent less than open-field farming.

On your home page, you make the following claim: “Urban Crop Solutions envisions to become the global independent reference of the fast-emerging vertical farming industry." How would you say this is possible?

At this time, vertical farmers are trying to juggle two widely different business plans: on the one hand, they spend capital developing and integrating an engineered solution and the biological corresponding know-how. On the other hand, they then apply this research to construct a vertical farm, operate it as farmers, and earn back the investment not only of the infrastructure, but also of the R&D that precedes it, as well as continues afterwards. In our opinion, this is a poor business plan because they have to earn back their R&D and their operational infrastructure investment with the sale of crops.

If we look at the more mature greenhouse industry, we get a sense of where the sector of vertical farming will eventually evolve. A greenhouse tomato grower that wants to set up a new production facility will not develop his own technology, but instead turn to the 15 best greenhouse project developers, ask for quotes, and select the one he feels most confident about. In that setup, we see technology companies focusing on providing systems, and growers focusing on farming. We start seeing a change in the mindset of vertical farmers along those lines today as well.

Let’s talk briefly about the upcoming World Agri-Tech Innovation Summit. What will you be presenting there?

We will begin with a company introduction, present our unique selling points, newest technology, projects and achievements.

While creating all these solutions, there indeed have to be challenges that need solutions. What would you then say are some of the actual challenges that farmers face today?

Traditional farmers are combating unreliable climate conditions, increased labor costs, crop diseases, crop pests, soil degradation and much more. Our solutions provide reliable alternatives to all of these concerns.

Existing vertical farmers from their end are struggling with the high labor costs associated with running non-automated vertical farms — requiring scissor lifts or stairs to harvest the higher levels of crop cultivation areas — as well as inconsistent quality in their production due to poor control of the different variables. Our fully automated and well-engineered system reduces labour costs and deviations from the ideal settings, respectively.

The vertical farm model is certainly a rising trend amongst start-ups. How did this movement come about?

Well, it’s like I said from the beginning. By 2050, more than 70 per cent of all people will live in cities. Added to that, in 2017 almost 300 million USD has been invested in vertical farming, creating more and more momentum.

To put things into perspective globally, which regions would you say have the biggest influence on the vertical farm boom?

In North America and South East Asia, we see the most vertical farms. In South East Asia, there is a lack of land to farm on and a variety of food safety issues. In North America, there are a lot of business opportunities with vertical farming technology due to the willingness of consumers to pay a premium for locally produced healthy crops.

City Roots Owners Talk About Their Decision To Downsize

Urban Farm Gets Back to Its Roots.

By Bach Pham

Sep 26, 2018

Bach Pham

There was a sense of calm between City Roots owners Robbie and Eric McClam as they worked on the field at the farm last week, preparing for the Glass Half Full Festival. After a busy first half of the year, the quiet moment was a welcome turn for the father and son.

The change came by choice.

Founded more than a decade ago, City Roots occupies a few acres in Columbia’s Rosewood neighborhood, near the Hamilton-Owens Airport. But recently, the community-minded urban farm began growing faster, expanding production at a second site.

“This past winter and spring we were scaling the farm from three acres to about an additional 30 acres to which we were planting a dozen or so acres of vegetables,” says Eric McClam. “We basically had five farms: a microgreen farm, a mushroom farm, a flower farm, a vegetable farm, and an agrotourism farm spread across two locations, 15-20 minutes apart. That was fun and exciting, but had its own new set of challenges.”

The size and scope of the changes was immediately felt. City Roots was branching in several directions with production, and struggling to make it all connect.

“We had over 200 different things we were growing between the farms,” Eric says. “No one can do 200 things well.”

The complexity of the farm’s rapid growth brought as many technical issues as it did benefits. City Roots was doing everything: growing, processing and delivering to local restaurants in Columbia and food hubs in Atlanta, Greenville and Charleston nearly every day of the week.

“We had three deliveries going on a day at one time on some occasions,” Robbie says. “We had vans in the shop, car repairs all the time.”

The breaking point hit over the summer when Eric fell ill and was forced to take some time off.

“What precipitated the scaling back and hard look at everything was I literally got shingles from stress this summer and had to stay home for a period of time,” says Eric. “While at home, I had time to take a hard look at what was holding that stress and recognizing that it was the diversity and scale of the farm. Everybody has a grounding moment in their life and says, ‘OK, what is important to me?’ The farm and family are important.

“So after making the hard decisions, we scaled it back to fit what works well for the farm. We recognized that getting better at what we do well and letting go of things that were painful to let go, especially reducing staff — some of whom had been here for many years — was something necessary for the direction of the business.”

Eric calls the decision to lay off employees “the hardest decision.” The farm went from 23 employees to about 15.

“We hope we are still in a good place with everyone. We just didn’t have the ability to retain them. We had to be nimble and change course. My role as the head farmer is to steer the ship. We were heading for a ditch, and we needed to get back on course.”

The McClams made several major changes in the past few months. Production at their second site was halted, and the community supported agriculture (CSA) program was cut.

“When we first started, the CSA was exciting and a good business model for us,” says Eric. “We never could quite get the volume of CSA we needed to make that diversified larger scale work, though. … We realized that we’re better suited to do a variety of things and bringing those to market and doing it that way.”

While the field side of the farm struggled to find the right identity, two parts of the farm actually have grown over the years: microgreen and mushroom production.

Microgreens went from being a small portion of the farm in the beginning to quickly becoming the biggest component of City Roots, seen not just in Columbia, but everywhere in the South from menus in Charleston to shelves in every Whole Foods in the Southeast.

“A lot of people grow organic vegetables, but not a lot of people grow microgreens and mushrooms,” says Eric. “Those are what we’re most known for, that’s our niche market and what works really well for us.”

City Roots plans to shift their focus to sharpening their microgreen and mushroom production, maintaining some small-scale flower production, and simply putting more time into the urban farm itself.

“We’re going to be putting more landscaping around the farm, more shrubs and trees, making the farm a prettier place and improving it as an event venue,” Eric says. “I’m excited about putting more emphasis here at the home farm and getting back to the roots at City Roots.”

Eric still plans to maintain the educational aspect of the farm. This year they doubled the number of school tours from last year, and plan to continue finding ways to share the farm with the community. They have also been exploring pickling, dedicating a portion of the farm to growing root vegetables and plants like ginger to contribute towards different recipes to sell at the farm.

There is still hope to do some large-scale gardening, especially with one particular product that has become a much-talked about agricultural item: hemp. The farm applied for the industrial hemp pilot program run by the South Carolina Department of Agriculture and is currently in the running to be one of the 40 farms certified to grow hemp in South Carolina.

“We are excited about that potential,” says Eric. “It’s a new niche market that we see a lot of potential for growth.”

Economics of Urban Ag

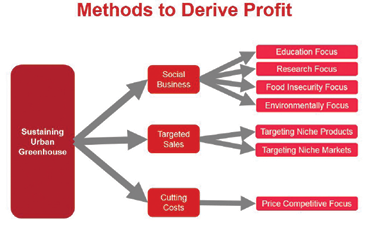

Targeting high-value, niche markets or products, and adapting a social business model can help urban greenhouses derive profit.

September 27, 2018

Robin G. Brumfield and Charlotte Singer

Editor's note: This article series is from the Resource Management in Commercial Greenhouse Production Multistate Research Project.

Urbanized agriculture is gaining momentum in response to increasing demands for locally produced fresh vegetables. Greenhouse or indoor vegetable production to meet local demands is the backbone for this evolving scenario. The viability of various indoor crop cultivation options demands proper documentation to guide appropriate recommendations that fit different production circumstances for growers.

Brooklyn Grange’s Brooklyn Naval Yard Farm

Photo courtesy of Brooklyn Grange

Recently a popular trend toward eating local, deemed being a locavore, evidenced by a growing social movement, has evolved (Osteen, et al., 2012). While the benefits of buying food locally are debated due to the economics of comparative advantages, consumer groups support urban agriculture for a number of reasons, such as to support local farmers; to provide local, fresh food in inner city deserts; to buy fresh food; to know from where their food is coming; and to respect the environment (Peterson, et al., 2015). Specifically, one study found that 66 percent of those surveyed welcomed more local food options because local food supports local economies (Scharber and Dancs, 2015).

Many consumers also cite environmental impacts as a reason to buy local, evidenced by one study finding that environmental factors were an important reason to buy locally grown food for 61 percent of those surveyed (Scharber and Dancs, 2015; Reisman, 2012). Another popular reason is to reduce food insecurity. USDA defines food insecurity as “a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food” (USDA ERS, 2017). Buying locally grown food can reduce food insecurity in that having local farms provides consumers who might not have previously had access to fresh produce the opportunity to purchase it. Some urban farms make a point of targeting food insecurity, and having local farms allows a city to rely less heavily on external markets to feed its population. Despite debate of realized benefits, consumers eat local food to feel good about it (Scharber and Dancs, 2015).

High capital costs

The low supply of special varieties such as these microgreens can drive a higher price to help cover the high costs of running a greenhouse.

Photo courtesy of Robin G. Brumfield

Regardless of the strength of their consumer base, the number of urban farms is still low due to the high costs that urban farmers face compared to rural farmers. Not only is the land more expensive, but also the limited plot size and probable contamination of the land with lead and toxins essentially necessitates the use of a greenhouse with high investment costs. Cost challenges that many urban greenhouse farmers face include securing funding, finding economies of scale, and facing high capital and operating costs. The energy necessary to heat a greenhouse through the winter makes utility costs high, the most productive greenhouse technologies are expensive, and land is of much higher value in cities than in rural areas (Reisman, 2012). Not to mention, the initial infrastructure cost involved in building a greenhouse is much higher than the costs that farmers growing in a field face. The costs of urban greenhouses vary greatly depending on size and type. The construction of, for example, a hydroponic greenhouse entails costs for site preparation, construction, heating and cooling equipment, thermostats and controls, an irrigation system, a nutrient tank, and a growing system (Filion, et al., 2015).

Another problem with growing in cities is shade from tall buildings and skyscrapers. Jenn Frymark, chief greenhouse officer at Gotham Greens, cites this as the primary reason that the business built rooftop greenhouses. This creates its own set of problems and increases costs compared to standard greenhouses on the ground. Other urban producers address the shade problem in cities by producing in buildings using vertical agriculture and artificial lights. However, this increases the costs even further because of the need for light all year. These high costs keep the number of urban farms small.

Marketing: quality optimization, high-value plant products, year-round production

Due to these high costs, urban greenhouses must derive profit in creative ways, such as targeting high-value niche products or markets, and producing year-round. Targeting niche products and markets allows urban farmers to charge a premium that covers the added costs of operating in the city. Targeting a niche product could entail producing special varieties of vegetables, like how Brooklyn Grange, a successful New York City-based greenhouse, grows microgreens and heirloom tomatoes. The low supply of these special varieties can drive a higher price to help cover the high costs of the greenhouse. To increase profitability, farmers can also find a high-end market (Sace, 2015).

Targeting a niche market could entail selling produce to high-end restaurants and supermarkets, such as Whole Foods, whose customers are already expecting to pay a premium price, or it could entail marketing produce specifically to locavores. In fact, one study found that, for example, consumers were willing to pay a $1.06 price premium on one pound of locally grown, organic tomatoes. In the same study, the researchers also found that urban consumers were more likely to buy locally grown produce, compared with rural consumers (Yue and Tong, 2009). The high costs associated with living in a large city means that cities have a high concentration of people who can afford to eat local in this way, and the demographics of large cities translate to a high concentration of people who also see value in eating locally produced food. Together, these create a market of locavores willing and able to pay a premium for locally grown produce.

By targeting niche products and markets, urban greenhouse farmers can take advantage of existing high-end markets to cover their relatively high costs. Since these producers use greenhouses, and a few use indoor facilities, they can produce year-round, thus providing a constant supply and a steady demand for their products.

Harlem Grown in New York gives students the opportunity to learn about agriculture and the food system in a hands-on nature.

Photo: Instagram: @harlemgrown

Agricultural jobs in urban settings and other social values

Adapting a social business model can open urban farmers up to alternate sources of funding. They may want to provide jobs to disadvantaged groups such as low-income inner-city dwellers, or people with autism. Some of these businesses have reduced labor costs through volunteerism, as individuals may be willing to volunteer on a farm that supports a social issue (Reisman, 2012). Some examples of causes that urban greenhouse social businesses focus on include education, research, the environment and food security. Harlem Grown in New York adds an educational component to the greenhouse, namely the opportunity for students to learn about agriculture and the food system in a hands-on nature, allowing the greenhouse to become eligible for funding from schools, governmental programs or donors particularly interested in education.

Targeting niche markets or products, adopting a social business model and finding inexpensive plots of land can help urban greenhouses derive profit.

Graphic: Charlotte Singer

Other urban greenhouses can, for example, pitch themselves to city dwellers as an environmentally friendly alternative to commercial farms, using less fuel for transportation and fewer chemicals. This could again render the greenhouse eligible to new sources of funding. AeroFarms in Newark, New Jersey, has adapted a combination of the previous two models. It uses environmentally friendly techniques and collaborate with Philip’s Academy Charter School (Boehm, 2016).

Greenhouses can additionally focus their business models on alleviating food insecurity by providing fresh produce to urban food deserts (US. New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, 2013). Unlike the previous cases, greenhouses that choose to focus on alleviating food insecurity would not be able to additionally use the method of targeting high-end markets, unless they make an effort to use the high-end markets to subsidize the cost of providing their produce to food deserts. An example of an urban farm targeting food insecurity is World Hunger Relief Inc. in Waco, Texas, which brings produce grown in its greenhouse to food deserts in the City of Waco at a market or discount cost. What these three options share is a business model that incorporates multiple bottom lines, which allows them access to new funding and volunteer labor to reduce costs.

As consumers increasingly look to eat locally produced food, for reasons such as to support the local economy, to protect the environment, to change food deserts and to understand better where food is coming from, urban agriculture is becoming a growing trend. Targeting high-value, niche markets or products, and adopting a social business model to provide agricultural jobs in urban areas, constitute some of the ways urban greenhouses to derive profit in a capital-intensive industry. By utilizing these techniques, individuals looking to start their own urban greenhouses can add value to their business and derive profit.

Farming The Cities: An Excerpt From Nourished Planet

Worldwide, there are nearly a billion urban farmers, and many are having the greatest impact in communities where hunger and poverty are most acute.

The following is an excerpt from Nourished Planet: Sustainability in the Global Food System, published by Island Press in June of 2018. Nourished Planet was edited by Danielle Nierenberg, president of Food Tank, and produced with support from the Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition.

By 2050, 70 percent of the world’s people are expected to live in urban areas, and if we’re going to feed all those people, we’ll need to continue to make cities and towns into centers of food production as well as consumption. Worldwide, there are nearly a billion urban farmers, and many are having the greatest impact in communities where hunger and poverty are most acute. For example, the Kibera Slum in Nairobi, Kenya, is believed to be the largest slum in sub-Saharan Africa, with somewhere between 700,000 and a million people. In Kibera, urban farmers have developed what they call vertical gardens, growing vegetables, such as kale or spinach, in tall empty rice and maize sacks, growing different crops on different levels of the bags. At harvest time they sell part of their produce to their neighbors and keep the rest for themselves.

The value of these sacks shouldn’t be underestimated. During the riots that occurred in Nairobi in 2007 and 2008, when the normal flow of food into Kibera was interrupted, these urban “sack” farmers were credited with helping to keep thousands of women, men, and children from starving.

The role urban farmers played in saving lives in Kibera is probably only a precursor of things to come. In large parts of the less developed world, as much as 80 percent of a family’s income can be spent on food. In countries where wars and instability can disrupt the food system and where the cost of food can skyrocket overnight, urban agriculture can play a fundamental role in helping prevent food riots and large-scale hunger. In that respect, promoting urban agriculture isn’t only morally right or environmentally smart, it’s necessary for regional stability.

But urban agriculture isn’t important only in sub-Saharan Africa or other parts of the developing world. In the United States, AeroFarms runs the world’s largest indoor vertical farm in Newark, New Jersey, where it grows greens and herbs without sunlight, soil, or pesticides for local communities in the New York area that have limited access to greens and herbs. Another group, the Green Bronx Machine, which is based in New York City’s South Bronx neighborhood, is an after-school program that aims to build healthy, equitable, and resilient communities by engaging students in hands-on garden education.

Across the Atlantic, in Berlin, Germany, a group called Nomadic Green grows produce in burlap sacks and other portable, reusable containers. These containers can be set up in unused space anywhere, ready to move should the space be sold, rented, or become otherwise unavailable. In Tel Aviv, Israel, Green in the City is collaborating on a project with LivinGreen, a hydroponics and aquaponics company, and the Dizengoff Center, the first shopping mall built in Israel. This collaboration provides urban farmers with space on the top of the Dizengoff Center to grow vegetables in water, without pesticides or even soil. Green in the City also provides urban farming workshops and training in the use of individual hydroponic systems.

Farm Family: Ernessi Farms

(Midwest Farm Weekly/WFRV)

Harvest season will come to a close in a matter of weeks, but not for one Ripon, WI farm. They do not rely on mother nature to dictate seasons. In fact, it is always spring at Ernessi Farms.

The weather is always perfect at Ernessi Farms to grow everything year round because they are able to control the entire growing environment from the lighting, to the temperature, and even the nutrients. Ernessi does all of this the basement of a Watson Street business and they do it hydroponically.

Bryan Ernst, owner of Ernessi Farms says that “because we're able to control everything down to the wavelength of the light of the plants receive we can fine-tune every single plant so that way they grow their optimum size.

Visit ErnessiFarms.com to learn more about the products they offer!

Chapter 11: Urban Farming In Tokyo

Toward an urban-rural hybrid city.

Linked by Michael Levenston

By Toru Terada, Makoto Yokohari, and Mamoru Amemiya

From Green Asia: Ecocultures, Sustainable Lifestyles, and Ethical Consumption

Edited by Tania Lewis Routledge, NewYork

Excerpt:

Cities are places of both consumption and production. There is actually a city that had already realized this future vision of Japan in which agro- activities are incorporated into society. It is Tokyo’s predecessor, Edo. Edo, one of a handful of the world’s megacities that had a population of more than 1 million at the beginning of the eighteenth century, was a garden city with numerous farms integrated into the city. Fujii, Yokohari, and Watanabe (2002) reconstructed the land use in Edo in the mid-nineteenth century based on historical documents and maps.

They found that, at the time, a little more than 40 per cent of land in Edo was used for agriculture and that numerous farms were interspersed in the urban area radiating outward for a distance of 4 and 6 km from the Edo Castle. Local production and local consumption were thoroughly enforced, with vegetables produced on farms within the city being consumed within the city. Meanwhile, Edo maintained an outstanding sanitary environment that was unmatched by any other megacity in the world at the time, whereby human waste generated in the city was returned to the farms. Describing it in modern terms, Edo was a smart city with relatively little environmental burden and high-quality amenities. The coexistence of city and farms was a manifestation of Edo’s advanced environment.

See book here.

Israeli Companies Promoting Urban Agriculture Techs

Dubi Raz, agronomy director of Israeli drip irrigation giant Netafim Global.

Source: Xinhua| 2018-10-13 03:09:37|Editor: yan

by Nick Kolyohin

JERUSALEM, Oct. 12 (Xinhua) -- Israeli companies and experts are part of a global effort to promote and develop urban agriculture technologies. They believe urban farming is the way to secure food supply around the world.

"There are three main technological ways to do urban agriculture, and we are involved in all of them by working with most of startups and companies in these field around the world," Dubi Raz, agronomy director of Israeli drip irrigation giant Netafim Global, said in an interview with Xinhua.

The technology which makes urban agriculture possible is the ability to grow crops without the need for land and sun. It is a revolutionary technology which makes it possible to produce food anywhere in the universe.

Instead of the sunlight, there is a special artificial light which is designed and adjusted to crop individually. This modification ensures perfect growing conditions.

The second revolutionary part of urban farming is the use of water or special substrate instead of soil to grow vegetables and fruits. These technologies make it possible to grow crops on walls or vertical layers.

Although the technology exists, it is still an expensive practice in most cases.

"Because it is costly to grow crops inside the city. It doesn't make sense to produce sample wheat, tomatoes or any other plants, which consume lots of expensive energy to provide the artificial conditions," Raz said.

"That's why most of the urban agriculture is applied to leafy vegetables with really short growing cycle," Raz explained.

However, not everyone takes economic factors as top priority.

Tagit Klimor is a founding partner of Knafo Klimor Architects and a senior lecturer at the Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning at the Israeli Technion Institution.

Knafo Klimor Architects designed a huge vertical productive wall at Expo 2015 exhibition in Italy, showing the world the possibility of growing wheat, rice and corn in building walls.

"In a sustainable economy, we need to put into consideration the damage to the nature, pollution, energy consumption and so on," said Klimor.

"In urban agriculture, we are giving exact amount of water and ingredients the crops need ... for example, all the water are coming from the growing facility usage," Klimor added.

For health issues, urban agriculture products are more fresh with more nutrition ingredients.

However, Israeli government wants to encourage local farmers to grow crops in the countryside instead of cities.

"There are only a handful of urban agriculture places in Israel, and they are pretty lame," Avigail Heller, head of Urban Agriculture Community Branch at the Israeli Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, told Xinhua.

Heller said that the Israeli government is not encouraging the urban farming. Taxes on urban farmers are higher than traditional agriculture farmers.

"Israel is a small country where the farm fields are a half-hour drive from the cities. So there is no initiative to grow crops in cities where the land is much more expensive," said Zvi Alon, director general of Israel Plants Board.

"Our mission is to continue to lead and improve our techniques of making more crops by using less water and soil. It is the real solution to the food shortage crisis," concluded Alon.

State Grant Program Offers Money, And Legitimacy, For Urban Agriculture

By Taryn Phaneuf | 10/09/2018

MinnPost file photo by Ibrahim Hirsi

Michael Chaney, a long-time advocate from north Minneapolis who founded Project Sweetie Pie, a grant recipient, said he approached lawmakers with the idea about four years ago.

Urban farming in Minnesota reached a milestone this summer, when the state announced the first round of grants for agriculture education and development projects in cities.

It’s the first time the state has allocated money specifically for urban agriculture, and it took several tries to get the legislation passed. Michael Chaney, a long-time advocate from north Minneapolis who founded Project Sweetie Pie, a grant recipient, said he approached lawmakers with the idea about four years ago. At the time, he saw plenty of interest in urban agriculture — but not the kind of financial support that exists for rural farmers. “I was disenchanted and discouraged,” Chaney said.

Advocates said state investment is crucial because it lends credibility to what Chaney calls the “changing face of agriculture.” Such state funding, even a small amount, can usher in a shift toward seeing urban areas as potential farms and their residents as fellow food producers.

That shift can also bring education and economic opportunities that are often more associated with rural areas. “Agriculture has been deemed corporate ag with rural roots and conventional farming techniques,” Chaney said. “What we’re proposing with urban farming is a whole reconfiguring. … What’s the role of urban communities in growing food?”

Rep. Karen Clark, DFL-Minneapolis, authored the bill, which called for $10 million annually to fund urban ag projects in cities throughout the state. The legislation prioritizes poor communities of color and Native American communities. Clark kept the idea alive at the state level for years, and finally made headway when legislators commissioned a study of urban agriculture that defined its scope and the purpose and identified policy recommendations.

The study cost $250,000, the same amount the Legislature eventually earmarked for urban ag grants for each year in the current budget. It’s far less than program advocates wanted, but it maintained the original intent, said Erin Connell, who administers the grants for the Minnesota Department of Agriculture. Eligible groups include for-profit businesses, local governments, tribal communities, nonprofits, or schools in cities of more than 10,000 people. Cities with between 5,000 and 10,000 people are also eligible if 10 percent of residents live at or below 200 percent of the poverty line, or where 10 percent of residents are people of color or Native American.

“It’s exciting for me so see the acceptance of urban ag as a new standard for ag production,” said Connell, who grew up in the Twin Cities metro area and didn’t discover her interest in ag until she started studying food systems at the University of Minnesota.

Urban agriculture’s impact

Growing food in the city is partly about improving residents’ diets and food security, but it also extends to building wealth, culture, and independence. “Community members were very vocal about wanting to bring the benefits of ag into various urban areas,” Connell said.

Jolene Jones, president and interim CEO of the Little Earth Residents Association, said the community received a grant for nearly $45,000, which they’ll use to teach more children to help in their gardens by creating a storybook that shows them how indigenous people farm in the city.

This fall, they’re learning to construct a hoop house that will extend their growing season, and learn how to grow the four medicines – sage, cedar, sweetgrass, and tobacco. “To actually be able to grow them, it will be awesome for them,” Jones said. “Culture is very sustainable. … the way to put culture in agriculture is to teach children the traditional value of their plants.”

A local food system – which includes everything from growing food to processing it to buying and consuming it – also creates jobs, income, and infrastructure. That’s the mindset used to justify public spending on agriculture development in Greater Minnesota, like one that helps farmers modernize their livestock operations by, say, expanding their facilities to hold more animals. That has visible impact, Peterson said, by providing more work for veterinarians and feed companies.

That’s exactly the kind of ripple effect local food advocates imagine in places like north Minneapolis. Project Sweetie Pie, for example, will put its grant toward establishing a greenhouse that will belong to a broad coalition of groups, who will use it to operate year-round, Chaney said. It’s another step forward in their vision to grow their local food economy.

The fight for funding

Urban agriculture joins a suite of initiatives funded through the Agricultural Growth, Research, and Innovation program (known as AGRI), which supports the state’s agricultural and renewable energy industries through various grants and loans.

AGRI was an important win for Minnesota agriculture when it was established in 2009. At the time, the state subsidized ethanol production. “When those payments were going to end, we got concerned we were going to lose investment into agriculture,” said Thom Peterson, who lobbies the state government with the Minnesota Farmers Union.

Advocates convinced the state to establish AGRI, and the program will allocate a little more than $13 million a year for fiscal years 2018 and 2019, according to the most recent report.

The Farmers Union backed the bill to add grants for urban ag to the AGRI program, Peterson said. And he sees its addition as a chance to expand public support for state ag funding as a whole. “There’s agriculture all over the state, including in the metro areas,” he said.

He credits Clark, who is leaving the Legislature at the end of her term, with pushing the matter forward for years, until Rep. Rod Hamilton, a Republican from Southwest Minnesota who heads the House Agriculture Finance Committee, got on board. “Urban ag is going to need a new champion at the legislature now that Karen Clark is gone,” Peterson said.

Connell repeated the concern, saying the top question facing the urban ag grant program is whether funding will continue past 2019. She said communities that benefit from urban farming, especially from the grants handed out these two years, will need to show up when 2020-2021 budget talks begin.

“Getting the funding this first time is very difficult,” Connell said. “I also feel like after you get that first round of funding, some people who may have been very passionate may get less interested. They might get comfortable in a sense. Every two years, we’re going to get a new budget. Every two years you’re going to have to fight to continue that funding until it’s been there long enough that it’s assumed it goes in the budget.”

Urban Farming 2nd Edition

From Introduction: “As Michael Levenston from City Farmer in Vancouver, Canada, notes, urban agriculture has gone from back page news to front page news.”

Linked by Michael Levenston

By Thomas Fox

CompanionHouse Books

2 edition (November 14, 2018)

Thomas Fox is a graduate of Fordham University and Fordham University School of Law.

Excerpt:

Comprehensive Guide to the Urban Farm Movement It doesn’t take a farm to have the heart of a farmer. Thanks to the burgeoning sustainable-living movement, you don’t have to own acreage to fulfill your dream of raising your own food. Urban Farming 2nd Edition walks every city and suburban dweller down the path of self-sustainability. It offers practical advice and inspiration for gardening and farming from a high-rise apartment, participating in a community garden, vertical farming, and converting terraces and other small city spaces into fruitful, vegetableful real estate.

This comprehensive guide to urban food growing will answer every up-and-coming urban farmer’s questions about how, what, where and why?a new green book for the dedicated citizen seeking to reduce his carbon footprint and grocery bill. Winner of the Benjamin Franklin Award in Home & Garden from the Independent Book Publishers Association (IBPA). Inside Urban Farming 2nd Edition Portraits of successful urban farmers DIY projects for container gardening Instructions for creating a garden calendar Recommendations for the most foolproof multi-zone plants Plans for companion gardening Time-saving advice about planting, seed starting, and harvesting City-hall survival tips for navigating your town’s ordinances Zone map and extensive resource guide

Read the complete article here.

Green Life Farms Hires Elayne Dudley as Sales Director

Green Life Farms, a hydroponic farm currently under construction in Boynton Beach, FL, hired Elayne Dudley as its Sales Director, marking a major milestone as the project continues working toward commercial operations in April 2019.

Hydroponic farm under construction taps experienced sales veteran for new role

Boynton Beach, FL (November 1, 2018) – Green Life Farms, a hydroponic farm currently under construction in Boynton Beach, FL, hired Elayne Dudley as its Sales Director, marking a major milestone as the project continues working toward commercial operations in April 2019. Dudley will spearhead bringing Green Life Farms’ fresh and local leafy baby greens to supermarkets, restaurants, and other distributors throughout South Florida.

“Elayne comes to us with deep knowledge of the produce industry and vast experience in sales and marketing,” said Mike Ferree, Vice President, Green Life Farms. “She will be an important asset as we continue to grow and prepare for commercial operations to begin early next year.”

Dudley has more than 20 years of experience in marketing and sales, helping to grow business at several companies, including CVS Health, Loyalty Builders and Inside Sales Group. She brings expertise in strategic customer relationship building and business development in both business-to-business and business-to-consumer settings. Dudley is passionate about providing both outstanding customer service to Green Life Farms’ supermarket and restaurant accounts, and providing consumers with the freshest, cleanest, tastiest baby leafy greens on the market.

For people who expect more out of the food that goes into their bodies, by demanding less of what goes into producing it, Green Life Farms produce will set a new standard. The produce will be grown locally, using farming practices that keep produce free from harmful additives, so customers are free to enjoy it all without worry or waste.

Green Life Farms, a hydroponic farm currently under construction in Boynton Beach, FL, hired Elayne Dudley as its Sales Director, marking a major milestone as the project continues working towardcommercial operations in April 2019. Dudley will spearhead bringing Green Life Farms’ fresh and local leafy baby greens to supermarkets, restaurants, and other distributors throughout South Florida.

About Green Life Farms

Green Life Farms is constructing a 100,000 square-foot state-of-the-art hydroponic greenhouse in Boynton Beach, Florida, with additional expansion planned in Florida and beyond. Commercial operation is expected to begin in April 2019. Green Life Farms will provide consumers year-round with premium-quality, fresh, local, flavorful and clean baby leafy greens that are good for their bodies, families, communities and planet.

# # #

Could the Future of Farming be Vertical?

Vertical farming is greener and more efficient than traditional agriculture, writes Natalie Mouyal

Photo: BrightAgrotech, Pixabay

Vertical farming promises a more sustainable future for growing fruit and vegetables. Instead of planting a single layer of crops over a large land area, stacks of crops grow without soil or sunlight.

The nascent technology enables farmers to grow more food on less land. Among the benefits, it reduces the environmental impact of transportation by moving production from the countryside to the cities, where most people live.

Dilapidated warehouses and factories around the globe are being transformed into urban farms to grow salads and other leafy greens at a rate that surpasses traditional farming techniques. LEDs provide the lighting plants need to grow, while sensors measure temperature and humidity levels. Robots harvest and package produce.

At one vertical farm in Japan, lettuce can be harvested within 40 days of seed being sown. And within two towers measuring 900 m2 each (actual cultivation area of 10 800 m2 and 14 400 m2), the factory can produce 21 000 heads of lettuce each day.

Indoor farming is not a new concept, as greenhouses have long demonstrated. It has existed since Roman times and can be found in various parts of the world.

Greenhouses are described in a historic Korean text on husbandry dating from the 15th century and were popular in Europe during the 17th century. In modern times they have enabled the Netherlands to become the world’s second largest food exporter.

Vertical farming offers a new take on indoor farming. Popularized by the academic Dickson Despommier, its proponents believe that vertical farming can feed millions of people while reducing some of the negative aspects associated with current agricultural practices: carbon-emitting transportation, deforestation and an over-reliance on chemical fertilizers.

Vertical farming is defined as the production of food in vertically stacked layers within a building, such as a skyscraper or warehouse in a city, without using any natural light or soil. Produce is grown in a controlled environment where elements including light, humidity, and temperature are carefully monitored.

The result provides urban dwellers with year-round access to fresh vegetables since they can be grown regardless of weather conditions, without the need for pesticides and have only a short distance to cover, from farm to plate.

Initially conceived by Despommier with his graduate students as a solution to the challenge of feeding the residents of New York City, vertical farming has since taken off around the world, most notably in the United States and Japan. According to the research company Statista, the vertical farming market is expected to be worth USD 6,4 billion by 2023.

High-tech farming

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, food production worldwide will need to increase by 70% by 2050 to feed a projected global population of 9,1 billion. Vertical farming seeks to address the dual challenges of feeding a growing population that, increasingly, will live in urban centres.

By repurposing warehouses and skyscrapers, these ‘high-tech’ greenhouses reuse existing infrastructure to maximize plant density and production. One vertical farm in the United States claims that it can achieve yields up to 350 times greater than from open fields but using just one percent of the water traditional techniques require.

In general, two methods for vertical farming are used: aeroponics and hydroponics.

Both are water-based with plants either sprayed with water and nutrients (aeroponics) or grown in a nutrient-rich basin of water (hydroponics). Both exhibit a reliance on advanced technology to ensure that growing conditions are ideal for maximizing production.

So as to produce a harvest every month, vertical farms need to control the elements that affect plant growth. These include temperature, requisite nutrients, humidity, oxygen levels, airflow and water.

The intensity and frequency of the LED lights can be adjusted according to the needs of the plant. A network of sensors and cameras collects data with detailed information about the plants at specific points in their lifecycle as well as the environment in which they grow.

This data is not only monitored but also analyzed to enable decisions to be taken that will improve plant health, growth and yield. Data sets sent to scientists in charge of the growing environment enable decisions to be made in real-time, whether they are onsite or at a remote location.

Automation can take care of tasks such as raising seedlings, replanting and harvesting. It can also be used to provide real-time adjustments to plant care. One factory plans to automate its analytical process with machine learning algorithms so that real-time quality control can take into account a diverse range of data sets.