Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Danone Invests in Urban Farming Business Agricool

French dairy giant Danone has taken part in a US$28m investment round in local pesticide-free fruits and vegetable business Agricool.

By Andy Coyne | 5 December 2018

Danone - investing in French urban farming business

The investment was made through its Danone Manifesto Ventures venture fund arm.

Urban farming business Agricool said the investment will allow it to pursue its ambition to make "excellent, pesticide-free fruits and vegetables accessible to all".

The other investors in the round included Bpifrance Large Venture Fund, French businessman Antoine Arnault via Marbeuf Capital, Docker co-founder Solomon Hykes, as well as a dozen other 'business angels'.

Existing investors - which include venture-capital funds Daphni and XAnge, Xavier Niel via the Kima Ventures venture-capital firm and Henri Seydoux, the founder of civil-drone business Parrot - also participated in the new funding round.

In the past three years, Agricool's teams have developed a technology to grow local, healthy fruits and vegetables more productively and within small and controlled spaces, known as "Cooltainers" (recycled shipping containers transformed into urban farms).

Agricool said that, thanks to this new funding round, it will be able to confirm its role in the development of this new type of agriculture, while positioning itself as a key player in the segment of vertical farming in France and worldwide.

It said it plans to multiply production by a hundredfold by 2021, in Paris first, then internationally starting with Dubai, where a container has already been installed.

Agricool has ambitions to employ 200 people by 2021.

Danone Among Backers of French Urban Farming Start-Up Agricool

French urban agriculture start-up Agricool has secured $28 million in its latest funding round, including an investment from Danone’s investment arm, Danone Manifesto Ventures.

Posted By: Contributor on: December 07, 2018

French urban agriculture start-up Agricool has secured $28 million in its latest funding round, including an investment from Danone’s investment arm, Danone Manifesto Ventures.

In the past three years, Agricool has developed a technology to grow local fruits and vegetables more productively and within small and controlled spaces, known as ‘Cooltainers’ (recycled shipping containers transformed into urban farms).

The Paris-based business said it is responding to reports which suggest that by 2030 20% of products consumed worldwide will come from urban farming – compared to 5% today.

Other investors in the round – which adds to $13 million previously raised – include Bpifrance Large Venture Fund, Antoine Arnault via Marbeuf Capital, Solomon Hykes and a dozen other backers.

With the new funding, Agricool aims to position itself as a key player in the vertical farming sector. The start-up hopes to multiply its production by 100 by 2021, in Paris first, then internationally, starting in Dubai, where a container has already been installed in The Sustainable City.

Agricool said that its challenge, and that of urban farming, is to help develop the production of food for a growing urban population which wants to eat quality produce, while limiting the ecological impact of its consumption.

In a statement, the start-up said: “Agricool strawberries are harvested when perfectly ripe and contain on average 20% more sugar and 30% more vitamin C than supermarket strawberries.

“The production technique makes for strawberries which require 90% less water to grow compared to traditional agriculture, with zero pesticides, and a reduced transportation distance reduced to only a few kilometers between the place of production and point of sale.”

Agricool co-founder and CEO Guillaume Fourdinier said: “We are very excited about the idea of supporting urban farming towards massive development, and it will soon no longer be a luxury to eat exceptional fruits and vegetables in the city.”

Urban Harvest: Holyoke Freight Container Home To High-Tech Produce Farm

By GRETA JOCHEM

Staff Writer Friday, December 07, 2018

HOLYOKE — Two 40-foot shipping containers sit in an empty lot in the middle of downtown Holyoke on Race Street.

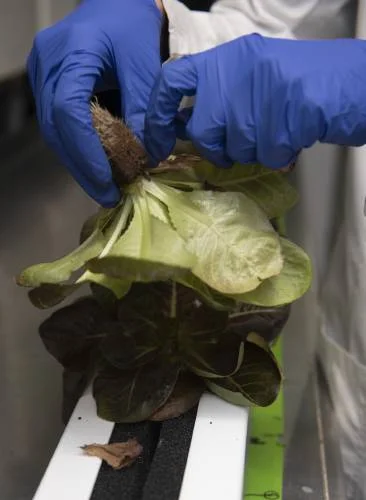

A passerby may not think twice about them, but inside one container an acre of lettuce is growing hydroponically, without the use of soil.

The inside of Holyoke Freight Farms looks more like a futuristic science lab rather than a farm. Sleek containers of romaine and butterhead greens hang vertically from the ceiling in neatly packed rows. The space is just big enough for a handful of people to stand inside with the plants.

The farmers have a lot of control: an electronic panel allows them to change the temperature and dispense nutrients, while lights can be turned on to give the plants a “daytime,” said Claire McGale, an intern with Holyoke Freight Farms and a sustainability studies student at Holyoke Community College. Inside the container she pointed out piping on the ceiling that helps deliver water to the plants.

It takes about eight weeks to grow the plants from seeds, and the container farm can produce 500 lettuce plants weekly, McGale explained.

MassDevelopment’s Transformative Development Initiative, which aims to spur economic growth in the state’s Gateway Cities, provided funding for the project. Holyoke Community College is leading the project; other partners include the City of Holyoke and the grassroots urban agriculture organization Nuestras Raíces. The refurbished shipping container is from the Boston-based company Freight Farms, which sells growing systems it has nicknamed “Leafy Green Machines” all around the world.

Some produce is sold to Gateway City Arts just down the street, and they are currently working to get more customers, said Alina Davledzarova, farm manager and a HCC alumna. Right now, she said, growing is happening in one of the two containers until demand picks up.

Roughly 10 percent of the produce will be donated to the college’s food pantry. “It’s the first time they’ve had fresh produce in the pantry,” said Insiyah Bergeron, Holyoke Innovation District manager and a fellow at MassDevelopment.

The project is also educational. “This is meant to be a training project,” Bergeron said, “to train interns from HCC and the community in the basics of hydroponic food production.”

The plan, Bergeron said, is to soon bring in a few Holyoke residents in an apprenticeship program to work in the freight containers and learn skills for a job in hydroponic growing.

“It’s also to get people to think about what farming could look like beyond the limited growing season,” she added.

In Holyoke – a city without a lot of farmland – the growing containers are useful, McGale pointed out. Plus, she added, they are not affected by erratic weather and storms. For example, farm fields have been dumped with a heavy rain this year and this fall was one of the rainiest on record for several areas around New England.

Another advantage: Greens can be grown all year.

“How many people can say that they’re farming an acre of lettuce in New England year-round and giving it to people down the street?” asked Davledzarova.

It is a lot of work though, Davledzarova and McGale agreed. The inside of the freight container needs to be kept very clean to avoid issues like algae growth and plants need to be handled with gloves and protected by hairnets.

How do the hydroponically grown greens taste? Said McGale of the lettuce: “My daughter eats spinach now … she’s seven.”

Greta Jochem can be reached at gjochem@gazettenet.com

Agricool Is 'Growing Food In The Cities Where You Live'

Agricool grows fruit in shipping containers in urban areas

Alex LedsomContributor

Agricool is a Parisian startup on a mission to grow delicious strawberries in inner city areas, at scale and for profit, which can be transported ‘from field to fork’ in just 20 km. What’s more, it’s a sustainable business that be replicated worldwide.

Agricool grows fruit in shipping containers in urban areasAGRICOOL

Agricool grows its strawberries in shipping containers using vertical farming methods; this is where food is grown in vertical shelves or on walls, to maximise the surface area used for cultivation. Founders Guillaume Fourdinier and Gonzague Gru are the sons of farmers from the north of France. As CEO Fourdinier explains, he arrived in Paris at age 20 and it wasn’t long before he was seriously missing ‘quality fruit and vegetables’ from the countryside. Strawberries are notoriously challenging to grow well, he says; they are fragile with a growing cycle and post-harvesting process which can be difficult to manage. Also, with increased urbanisation, more and more food is transported into city areas pumped with pollutants to ensure they survive the journey which usually means they are less tasty. He is convinced that ‘strawberries have got lost in the last 30 years’.

Founders Guillaume Fourdinier and Gonzague GruAGRICOOL

And so the two partners began to see if it was possible to find a way to harvest the highest quality strawberries under urban conditions. Fourdinier is keen to point out that this business didn’t start as a shipping container business — the idea to use containers was much more practical and organic. They had previously used containers on their families’ farms and once they had used up all the room in their apartment, it was ‘the easiest room to find’ and highly functional because the size is standardised, you can transport it easily, and you can scale up profitably.

The inside of a cooltainerAGRICOOL

Growing strawberries in containers is an incredibly technical process with an extraordinary amount of factors to control. The fruit has a three-month cycle; two months from the day of planting to the first harvest, and then there is one month where the fruit can be harvested every day. Climate-wise, the temperature, air humidity and carbon dioxide must all be varied in quantity over the course of the three-month cycle. Agricool uses a closed-loop water system, meaning that they fill a tank for three months and use the same water over that period, which uses 99% less water. When strawberries are grown in a field, they are planted in soil where the roots soak up moisture. Agricool uses aeroponics instead of a soil-based system, where the plants’ roots are directly exposed to the air, taking in moisture from mist sprays. Agricool doesn’t aim for having a completely bacteria-free environment — believing this to be impossible, it grows its own ‘friendly’ bacteria, putting ‘friendly fungi in the water and friendly insects into the containers’, to protect against the risk of damaging insects finding a way inside. In this sense, the containers grow their own antibodies. Finally, the lighting is key. Agricool uses LED lights, not just to regulate the intensity of light but also the spectrum of light that the strawberries receive. Fourdinier says that one of the biggest challenges for vertical farming is to get this intensity just right. And never mind the calculations for the number of bees in bee boxes required for pollination... The one drawback always levelled at vertical farming is the amount of energy it consumes but Agricool counter this argument by using renewable energy. They believe it is better to grow food locally in large cities with artificial lighting rather than transporting produce from far away, where it loses its taste and chalks up the food miles.

Harvesting strawberriesAGRICOOL

The business model is to sell directly to the customer, without a middleman and this strategy appears to be working; French customers have been abandoning poorer quality fruit and vegetables sold in some French supermarkets, and so chains have been very receptive to Agricool’s new agricultural model. The company produced its first box of strawberries in October 2015 and now have over 60 staff.

The strawberries look like artAGRICOOL

Funding came in two funding rounds from European venture capitalists. Its CEO adds that it isn’t possible to be profitable if you are not vertically integrated; that is to say, you must own and produce the products you use in your supply chain. And this has been where the real challenge lies, as to develop the best possible LED light for its containers, in the most profitable way, Agricool has had to develop its own technology. They now design and manufacture their own LEDs, which are three times more efficient for their lighting needs at the energy spectrum they require than other LEDs they could find.

A cooltainer in Bercy, ParisAGRICOOL

Urban vertical farming is incredibly on-trend. Just like like the mushroom farms in New York, people are turning to more sustainable farming in urban areas for the quality and ethos but also the urban aesthetic — under the luminous lights, this fruit looks more and more like art. The difference between Agricool and its competitors is that it believes it has the recipe to scale up. Fourdinier explains,

Indeed, Agricool already operates a container in Dubai from its French headquarters.

The end result AGRICOOL

The downsides are really the same as the upsides in that the opportunities are immense but the technology makes each stage a huge challenge. It isn’t a straightforward business; a truth highlighted by the fact that 70% of its staff are in R&D.

The harvest AGRICOOL

And the statistics are impressive for this startup aiming to ‘feed the cities of tomorrow’. Its strawberries have 30% more vitamins than conventional strawberries and contain 20% more sugar. Its containers can yield 10 times as much as a greenhouse and 120 times as much as a field. And while Agricool is keen to point out that farming today is mostly woods and rice, which are difficult to grow vertically at the moment, it believes in 30 years time, about 30% of what we grow will be farmed in cities, for cities. Today Agricool sells about 200kg of strawberries each week but in one years' time, they expect this to be 2,000kg, ten times as much. As Agricool begins to branch out into tomatoes, which are similar in complexity to strawberries, its slogan ‘we grow food where you live’ has never been more true or more deliciously tempting.

German University Conducts Research On Urban Farming In Growtainer

Mobile Greenhouse Is Financed By Gemüsering Thüringen

The Weihenstephan-Triesdorf University of Applied Sciences received a growtainer at the beginning of the year, intended for research and teaching purposes. The "Gemüsering Thüringen" company is financing the mobile greenhouse for a period of ten years. This is a fully insulated container that has been specially modified to create optimal production conditions for vertical planting systems, regardless of the environment and climate.

Since that time, the growtainer has been put into operation and is now used in particular for research projects in the field of "urban farming". Prof. Dr. Heike Mempel heads the project group of the same name, dealing with scientific questions on possible advantages and disadvantages of a closed indoor farm without sunlight.

Indoor-Farming

Horticultural engineer Ivonne Jüttner is involved in the project "Product Quality and Resource Efficiency in Plant Production in Indoor Farming Systems" with an economically and ecologically meaningful cultural selection and the development and optimization of the associated procedures in a completely closed culture area. It compiles input/output balances of all material and energy flows, evaluates them with regard to sustainability and with the overriding goal of resource conservation. The project is funded by the Bavarian Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Forestry.

Another experimental setup examines the transpirational behavior of the growing plant. In the closed environment of the container, this parameter plays a key role. The transpiration flow through the plant is the driving force for nutrient and water uptake by the roots and it affects plant growth. At the same time, perspiration leads to increased humidity in the enclosed culture area. This must be removed by technical means, after which it is returned to the irrigation system in order to maintain the water cycle. This in turn results in an important advantage of indoor farming systems: water consumption is reduced enormously. The water absorption of the plant also influences the consequent dry matter of the products and thus their quality. Ivonne Jüttner is currently working on recording and visualizing the temperature and humidity distributions, as well as the air movement caused by the two incorporated fans.

LED lighting

The culture system and the design of the container significantly affect the climate in Growtainer. The homogeneous and exactly controllable culture guidance in closed systems with LED exposure in particular is a decisive advantage over conventional culture systems. The ability to precisely adjust the climate and growth conditions influences growth and ingredients in a targeted manner. These freely adjustable conditions allow a year-round and consistent production on site. In the coming year, a scientific assessment of the functionality of the Growtainers will be created. As soon as any weak points have been identified, the technical equipment can be optimized as the project progresses.

Using modern measuring and sensor technology, data on resource consumption and plant growth are recorded over the entire project period. Despite the use of energy-saving LEDs and good insulation of indoor farms, scientific studies show that energy use is the most critical factor compared to traditional culture methods. Nevertheless, the entire resource efficiency is mainly due to a reduced use of water and pesticides as the major advantage of indoor production. A comprehensive scientific analysis of the possible uses and limitations of closed indoor farming concepts using the example Growtainer, with subsequent practical evaluation of the results, in any case will be an important prerequisite for opening up application areas and fields of activity for horticulture in this innovative segment.

Smart Greenhouse Management System

The combination of the findings from the "Process Simulation based on Plant Response (Prosibor)" project, with project results from the Growtainer trials, will make it possible to compare indoor systems against conventional greenhouse production. Through the "Prosibor" project, a sensor-based intelligent greenhouse management system will be developed in cooperation with the Humboldt University of Berlin and the company RAM from Herrsching. Ivonne Jüttner will also develop a comprehensive analysis of potential plants that could be of interest for cultivation in pure artificial light systems. A special focus will lie on the potential added value that cultivation with artificial lighting systems could offer over cultivation under glass.

The added value can be a result of the increase in desired ingredients, the year-round production of, for example, flowers or fruits, production without the use of pesticides, or other criteria. As part of the study "Substance Use of Crops for the Chemical Industry", the HSWT, together with the State Research Center for Agriculture and other project partners, had already analyzed potentials for regional cultivation of medicinal and aromatic plants and evaluated initial approaches to indoor production.

Photosynthesis

In one of the two compartments of the Growtainers, students of the 5th Horticulture semester will carry out the first plant experiments in the greenhouse module. For example, they are investigating the suitability of different LED lights for the culture of Asian lettuces. The plants are hydroponically cultivated on several layers, one above the other. The energy required for the photosynthesis of plants is provided via LED modules at each shelf level. These immerse the interior of the Growtainer in a purple light; a combination of the blue and red spectral ranges. This light combination is used very efficiently for photosynthesis by the plants. To the human eye, however, it is rather uncomfortable, which is why any activity within the Growtainer is restricted to the use of safety goggles or with the LEDs switched off. In this exposure, the leaf colors of the plants might also not be judged correctly, which complicates an assessment of the nutritional status of the plants.

Findings from the already completed project "Energy Saving and Increased Efficiency in Horticultural Production with LED Exposure Systems" also show that for most plants an even broader spectrum of light, in addition to blue and red, optimizes the product quality: a supplement of yellow and green light, for example. This spectrum then appears white to the human eye, and the plants growing under the LED lights will have a natural green color, which facilitates not only positive growth effects but also the necessary work being done in the Growtainer. The determination of the ideal light spectrum for different plant species and their stages of growth is also an important issue in the research of the Growtainer.

For more information:

Hochschule Weihenstephan-Triesdorf

Am Hofgarten 4, 85354 Freising

Tel: +49 (0)8161 71-3416

Fax: +49 (0)8161 71-4402

www.hswt.de

Publication date : 12/7/2018

France: Agricool Raises 28 Million US Dollars For Urban Farming

With the announcement of a new funding round of $28 million, in addition to the $13 million previously raised, Agricool pursues its ambition to make pesticide-free fruits and vegetables accessible to all. Through its innovative concept, the company has paved the way for a new form of urban and technological agriculture, seeking to meet the ever-increasing demand for locally produced food and the expansion of local distribution networks.

The company has raised funds from new investors including Bpifrance Large Venture Fund, Danone Manifesto Ventures, Antoine Arnault via Marbeuf Capital, Solomon Hykes, and a dozen other business angels passionate about Agricool’s mission. The existing investors, which include daphni, XAnge, Henri Seydoux and Xavier Niel via Kima Ventures, have also participated in this new funding round.

Taking the lead in a booming market

According to UN reports, in 2030, 20% of products consumed worldwide will come from urban farming (compared to 5% today). In the past 3 years, Agricool’s teams have developed a technology to grow local, healthy fruits and vegetables more productively and within small and controlled spaces, known as “Cooltainers” (recycled shipping containers transformed into urban farms). Thanks to this new funding round, Agricool will be able to confirm its role in the development of this new type of agriculture, while positioning itself as a key player in the segment of vertical farming in France and worldwide. Agricool plans to multiply by a hundred its production by 2021, in Paris first, then internationally starting with Dubai, where a container has already been installed for several months in The Sustainable City.

The emergence of a new profession with the recruitment of 200 people

The deployment of these production modules will be made possible thanks to the recruitment of over 200 people in the Paris area and around the world, from now until 2021. This will result in the emergence of a new profession: the Cooltivator - an entrepreneur and urban farmer hybrid. These “market gardeners of the future” will play an important role in producing this new type of local, healthy food made accessible to all.

Cities of tomorrow

The challenge of urban farming and for Agricool is to help develop the production of food for a growing urban population who wants to eat quality products, while limiting the ecological impact of its consumption. Agricool strawberries are harvested when ripe, and the company claims they contain on average 20% more sugar and 30% more vitamin C than supermarket strawberries.

"Paris is dreaming of itself as an agricultural city", according to the ambition of the Paris City Council, and many metropolises like London, New York and Singapore share the same approach. "We are very excited about the idea of supporting urban farming towards massive development, and it will soon no longer be a luxury to eat exceptional fruits and vegetables in the city", stresses Guillaume Fourdinier, co-founder and CEO of Agricool.

For more information:

agricool.co

www.bpifrance.fr

www.danoneventures.com

www.daphni.com

www.XAnge.fr

Publication date : 12/4/2018

Freight Farm To Grow Vegetables For Detroit Homeless

Lettuce seedlings grow under grow lights in seedling troughs in a shipping container at Cass Community Social Services on Wednesday.(Photo: Todd McInturf, The Detroit News)Buy Photo

Candice Williams, The Detroit News | . Nov. 28, 2018

A 40-foot shipping container transformed into a freight farm will be used to grow vegetables for 700,000 meals served by Cass Community Social Services each year to those in need.

The donation of the container from the Ford Motor Company Fund is part of a $250,000 grant Cass Community Social Services received through the Ford Motor Farm project.

With the use of a hydroponic system and LED lighting, the farm operates without pesticides, sunlight or soil. It also uses 90 percent less water than an outdoor garden.

“It means fresh produce all year round, which is really huge,” said Faith Fowler, executive director of Cass Community Social Services. “Homeless people have a number of issues that are exacerbated by junk food, poor nutrition. To be able to have fresh food every day. Salads and greens and herbs are good for them.”

Freight Farm assistant Charlotte Gale of Detroit inserts seeds into peat moss pods, where they start to grow, in a converted shipping container at Cass Community Social Services in Detroit. (Photo: Todd McInturf, The Detroit News)

The first crop of vegetables will be ready to harvest in two to three weeks, said Kathy Peterson, the farm freight supervisor.

Currently, red leaf and butterhead lettuce plants are in various stages of growth inside the 7.5-ton shipping container stationed inside a garage space at Cass Community Social Services on Rosa Parks Boulevard. It only takes about five days for a lettuce seed to sprout and eventually be transferred to a plant wall where it will grow before it is harvested to eat.

“We have just started this endeavor, but I do know we can produce hundreds of thousands of produce a year,” Peterson said.

The project was the idea of a “Thirty under 30” team, Ford’s philanthropic leadership program, according to Jim Vella, president of the Ford Motor Company Fund and Community Services. The group initially thought to create a farm in the bed of a Ford F-150, and that idea evolved into the idea of growing vegetables inside a shipping container.

Cass Community Social Services received earlier this year a Ford F-150 with a garden bed that uses to teach healthy eating habits at local schools. The Ford Mobile Farm runs during the spring and fall.

“It not only provides produce to the kids, but it also educates and teaches kids that maybe didn’t know that carrots came from the ground, that you can pull from the ground and eat fresh delicious food,” said Chris Craft, a member of the “Thirty under 30” team.

Lettuce grows in vertical grow columns. (Photo: Todd McInturf, The Detroit News)

“However, we realized that education was only one part of the solution and that we also needed to address systemic unemployment and also food deserts that had no availability of fresh produce.”

Craft said the team researched and found the concept of using recycled shipping containers as farms. Cass Community Social Services was selected for the grant.

Fowler said the nonprofit will also use the grant money to employ developmentally disabled adults at the freight farm.

“We anticipate hiring between three and five men and women working there as a job-training site and some potentially for long-term,” she said.

cwilliams@detroitnews.com

Twitter: @CWilliams_DN

Container Farms: A New Type of Agriculture

Innovators within the produce industry are breaking the boundaries of food production

August 20, 2018 6:00 AM, EDT

Innovators within the produce industry are breaking the boundaries of food production — by growing crops not in fields, but in recycled shipping containers.

This modern twist on farming is designed to bypass some of the challenges and restrictions that farmers traditionally have faced, such as extreme weather, pests and limited growing seasons.

By overcoming these limitations, farming operations are capable of producing more food and growing certain crops in regions that otherwise would have had to import them.

By growing this food locally, suppliers are able to cut out the long travel distances often necessary to transport these foods to certain markets.

According to Jeff Moore, vice president of sales at produce supplier Tom Lange Co., shorter travel distances provide numerous benefits, such as fresher product, reduced transportation costs, less waste and fewer empty shelves at markets.

The use of innovative farming methods also is being pushed in Canada. Grocery retailer Loblaw Companies Ltd. announced plans to spend $150 million more each year with Canadian farmers by 2025. As part of that effort, the company pledged to help farmers implement growing techniques that will enable them to produce fruits and vegetables in Canada that the country has traditionally imported.

Freight Farms and Tiger Corner Farms are two companies that are growing produce in shipping containers through the use of hydroponics and aeroponics — methods of growing plants without the use of soil.

Freight Farms is working with NASA to find ways to grow produce in space. (Freight Farms)

Both companies use nutrient-rich water as a substitute for soil, but beyond that, their container farms are quite different.

Tiger Corner Farms’ farming units consist of five shipping containers; four are used for farming and the fifth one is used as a working station where the plants germinate and as a post-harvest station.

Tiger Corner Farms, based out of Summerville, S.C., is a family company that began with the combined interest of Stefanie Swackhamer, the general manager, and her dad, Don Taylor.

Through Grow Food Carolina, a nonprofit organization focused on preserving farming in South Carolina, Tiger Corner Farms has partnered with two other companies: Vertical Roots and Boxcar Central. Tiger Corner Farms manufactures farming units from recycled shipping containers, Boxcar Central works on the automation of the hardware and software used for these container farms, and Vertical Roots deals with the production of the produce.

With Tiger Corner Farms’ shipping container farms, Vertical Roots can increase food production. Having 13 farms in total, Vertical Roots is able to produce about 40,000 heads of lettuce in about half the time it would take a traditional farm.

Vertical Roots sells its produce to grocery stores such as Whole Foods and Harris Teeter.

Vertical Roots says it can produce 40,000 heads of lettuce in about half the time of a traditional farm. (Tiger Corner Farms)

For Vertical Roots, founded by Andrew Hare and Matt Daniels, working with Tiger Corner Farms was a no-brainer.

“Providing cleaner, fresher, better access to food was something all four of us were wanting to do. They wanted to provide jobs and educate people on the importance of sustainable agriculture, and we wanted to do the same thing,” said Hare, Vertical Roots’ general manager. “We wanted to bring transparency and education and empowering our community in knowing where their food comes from and how important the freshness and quality is.”

Meanwhile, Boston-based Freight Farms offers a hydroponic “farm in a box,” dubbed the Leafy Green Machine, built entirely inside a single 40-foot shipping container.

The company, founded in 2010 by Brad McNamara and Jon Friedman, also offers a farming service and mobile app, Farmhand, to aid farmers in monitoring their farms.

Freight Farms’ customers range from individual farmers to universities and corporations.

One of those customers is Kim Curren of Shaggy Bear Farm in Bozeman, Mont., which provides local restaurants with leafy greens that aren’t grown in the region.

Someday, hydroponic farming might even play a role in space exploration and colonization.

Freight Farms is working with NASA and Clemson University to improve the efficiency of its farming units in the hopes of eventually using them in space.

Joshua Summers is one of the professors at Clemson that worked on the project. Professors Cameron Turner and John Wagner and students Doug Chickarello, Malena Agyemang and Amaninder Singh Gill also worked on the project.

Lettuce grows inside a climate-controlled container farm from Tiger Corner Farms. (Tiger Corner Farms)

In order to enable the farming units to work in space, the Clemson team is focusing on making it a closed-loop system by looking at thermal and electrical loads of the LED lights as well as the heating, ventilation and air conditioning unit.

While working on this project, there is one major issue that Summers said needs to be taken into consideration.

“One of the major issues in moving into space is gravity. As you move away from gravity, a lot of their growing patterns are based on plants growing in a specific way,” Summers said. “Now you don’t know exactly how they are going to grow, so it’s going to be a bit more random, so we have to change some of the geometric layout to make it more efficient in terms of volume.”

Clemson, NASA and Freight Farms are working on a new proposal to continue this project.

Through its work with individual farmers as well as organizations such as NASA, Freight Farms is taking steps toward its goal of empowering anyone to grow food anywhere.

Step Inside The Hydroponic Farm Supplying Greens To Legacy Hall

Sprouting up: Margot Masinter holds a flat of microgreens grown inside a recycled shipping container. Billy Surface

With Doodle Farms, Margot Masinter is ready to give North Texas something homegrown to graze on. First stop: Legacy Hall.

BY STACY GIRARD

PUBLISHED IN D MAGAZINE JULY 2018

Growing up, Margot Masinter had little interest in dresses or dance classes. Instead, when she wasn’t dodging hockey pucks shot at her by her two older brothers, you could find her outside, digging in the dirt. It’s how she earned her family nickname, Doodlebug.

It was while in high school, during her first summer job working on a farm in Asheville, North Carolina, when she considered her interest might be more than just a recreational pastime. Proof came while attending Middlebury College, pursuing a degree in environmental studies. Her passion and education were further shaped through courses in farming and food policy, and part-time jobs: growing crops at Dallas’ Eat the Yard, establishing new colonies for the Texas Honeybee Guild, and working at an apple orchard in Vermont.

Trading acres for square feet, Masinter purchased a refurbished and recycled shipping container from Dallas-based Growtainer.

In Masinter’s case, some things never change. The 23-year-old natural beauty still prefers planting to primping and faithfully answers to her pet name—a name that opportunely serves as the DBA for her urban farming start-up, Doodle Farms, which supplies local restaurants with sustainably grown produce.

“We need more small-scale farmers,” she says. She expressed her convictions to her father, Mark Masinter, a successful real estate investor and developer and a partner in the 250-acre Legacy West development. The conversation yielded the idea of an on-site hydroponic farm that would service the Legacy Hall food stalls and area restaurants.

Trading acres for square feet, Masinter purchased a refurbished and recycled shipping container from Dallas-based Growtainer to house her chemical-free greens and herbs. The 53-by-10-by-9 metal box is docked on the Hall’s second floor, overlooking the outdoor Box Garden and music stage. Outfitted with LED lights, grow racks, fertilizing tanks, an irrigation system, and an AC unit with fans that control airflow and regulate temperature, the Growtainer provides a perfectly controlled growing environment.

Before she’d harvested her first crop, Masinter had already secured business with Legacy Hall’s Whisk & Eggs, Bravazo Rotisserie, and Détour, as well as other local restaurants—Sixty Vines, Haywire, The Ranch at Las Colinas, Whiskey Cake, Shinsei, Town Hearth, and Imōto, Tracy and Kent Rathbun’s new Pan-Asian concept. And her dad is such a believer in his daughter and the container-to-table concept that he became her partner in the company. “I loved the idea and wanted to be a part of it,” he says.

Masinter’s fast-cycle microgreens and other highly perishable crops—able to be harvested every eight to 28 days—are densely planted and require very little fertilizer. Masinter admits it is not the most sustainable way to farm—“You still have to use electricity,” she says—but growing in an urban environment requires compromises. “I’ll learn a lot this year and make any changes I need to,” Masinter says. “If anything, it will be a good experiment.”

Her next sustainable urban farm, a procession of raised beds, is already planned on a Henderson Avenue plot across from Gemma. This time, she’ll be back on terra firma and doing what she loves most—digging in the dirt.

Reusing Shipping Containers: Thinking Outside The Box

Let us introduce you to some of the creative-minded people who - literally - think outside the box!

By: AJOT | Oct 04 2018 | Intermodal News

Boots are made for walking and containers are made for shipping, right? Well, not if you ask everyone! Today, we see an exhilarating creativity in the reuse of shipping containers - living spaces, hotels, bars, pop-up stores, emergency shelters, bridges, art projects, and urban farming - the list goes on. Greencarrier Liner Agency loves the idea of recycling and innovation. Let us introduce you to some of the creative-minded people who - literally - think outside the box!

Urban farming – growing crops inside shipping containers

Freight Farms has found a way to grow crops inside shipping containers. Their hydroponic farming system called The Leafy Green Machine uses hi-tech growing technology to transform discarded shipping containers into mobile farm units. Each farm can produce as much food as a two-acre plot of land on a much smaller plot than is required by traditional crops.

As the outdoor climate has no impact on the conditions inside the container, food can be produced throughout the year and in any location. The project truly taps into the growing trend for urban farming and reduces the ecological footprint of food production.

Life uncontained – living inside Evergreen Line shipping containers

For the claustrophobic reader, it is now time to cover your eyes! After spending years not knowing what to do with their lives, this couple decided to chase what made them happy. Inspired by their past road trips, the hippies of the seventies, and Elon Musk, they chose to risk everything: They sold their traditional home, quit their jobs, and moved from Florida to Texas to build their dream debt-free net zero shipping container home using a couple of Evergreen Line Shipping containers. Are you intrigued? Follow their journey on YouTube!

A piece of container artwork you just can’t take your eyes off

As a part of his project “Women are Heroes,” the French artist JR turned shipping containers into a stunning piece of floating art. The picture assembled on the containers represents the eyes of a woman called Elisabeth who lives in the Kibera slums in Nairobi. When JR met and photographed her, she said “Make my story travel with you.” Using thousands of strips of paper placed by dock workers on the sides of the containers, JR created two eyes gazing at the world while travelling the oceans – two eyes belonging to women who will never travel across those oceans – made possible by art.

Container skyscrapers to replace slum housing

CRG Architects have come up with the concept for Container Skyscraper. The idea is to provide temporary accommodation to replace slum housing in developing countries. As many cities are facing unprecedented demographic, environmental, economic, social and spatial challenges, stacking recycled shipping containers to create cylindrical-looking towers can create high-density, cost-effective housing in urban areas. This is a truly innovative idea both in terms of CSR and the environment.

Container village startup hub for young companies

Dutch architect Julius Taminiau has created a temporary startup hub in Amsterdam using shipping containers. He has turned a derelict patch of land into a low budget, temporary space for young companies. In this dynamic village, the startups will inspire, collaborate across sectors, exchange knowledge and produce unexpected and paradigm-shifting creations. As the containers are placed upon concrete tiles, everything can be reused when the village is taken apart in the future and no trace will be left – an eco-friendly and innovative solution, which we are all about at Greencarrier Liner Agency!

3 reasons for reusing shipping containers.

As exemplified above – shipping containers can be so much more than just a box to ship commodity in. The reason for reusing shipping containers for other purposes than shipping is not only that they are extremely flexible, can solve a bunch of problems and be used in such innovative, unique, creative and cool ways – there is much more to it.

When containerisation conquered the global trade, shipping containers were standardised for intermodal freight transport. The standardisation made it possible to transport larger freight volumes and use different modes of transport without having to unload or reload the goods. Today, shipping containers still serve their purpose, but also provide great advantages when used as Intermodal Steel Building Units (ISBU).

1. Shipping containers are excellent construction material

From a structural point of view, containers are excellent construction material. As they spend the majority of their lifetime outdoors, the material is ideal for exposure to the elements of nature. The steel construction and design provide protection and strength as well as structural support and a long lifespan. The corner assemblies and locking mechanism also provide stability when multiple containers are being used in the construction of a building.

2. Buying empty shipping containers can be cost-efficient

Looking at costs, the reuse of shipping containers can be cost-efficient. A shipping container’s initial purpose is to carry cargo at sea, therefore it has to be cargo worthy throughout its lifespan. Most containers are finished as shipping containers after ten years in service and they are being replaced. Even though container stock is tight for most shipping lines, there is a big aftermarket for those replaced units retired from service at sea. To use those units as building material is inexpensive compared to traditional materials, such as wood, bricks or steel.”

3. Reusing shipping containers is sustainable construction practice

Recycling of any sort is eco-friendly. This is especially true when it comes to reusing shipping containers. It is, without doubt, sustainable construction practice; recycling unused containers for construction material puts an unused product to use while at the same time cleaning up spaces such as ports and shipyards. Shipping containers are also excellent for making use of solar power and can be insulated with eco-friendly materials.

An H-E-B-Owned Central Market Location In Dallas Sells Store-Grown Produce

Fresh Starts On The Perimeter

By Carolyn Schierhorn - 2018

Whether in a rural area or an urban hub, grocery retailers today are leveraging their fresh departments to differentiate their overall brand and their individual private brands from the competition. Across all generations of consumers, but especially among millennials, fresh food has an aura of healthfulness and excitement that far surpasses the packaged food products in the center store.

But “fresh” today doesn’t just refer to the produce, deli, “grocerant,” meat, seafood, bakery and dairy departments, according to Nicole Peranick, Stamford, Conn.-based Daymon’s senior director for culinary thought leadership, who shared her insights during Store Brands’ “Power of Private Brands” webinar series last year. “Fresh has taken on an expanded meaning, and solving for this new interpretation is really imperative to capture and retain customers,” she says.

As the Daymon white paper “From Shopper to Advocate: The Power of Participation” makes clear, fresh has become “the gateway to shopper loyalty.” To win consumers’ trust, grocery retailers must succeed in engaging customers at multiple touchpoints on the store perimeter and even before they walk into store — delighting shoppers with delicious samples, a cornucopia of colors and fragrances, high-energy food prep and cooking demonstrations, access to community resources such as representatives from local businesses or nonprofits, opportunities for “co-creation” and “personalization,” and more.

Under this broader definition, fresh could apply to a health & beauty section that allows shoppers to sample various botanical skincare products and aromatherapy oils, a wellness department coordinated by a registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN) who can help customers navigate the store and shop for their unique dietary needs, an in-store exhibition showcasing the work of local artists and craftspeople, or even a 3-D printer that lets shoppers scan photos and create ceramic figurines of themselves and loved ones (available at several Asda stores in the United Kingdom).

As West Des Moines, Iowa-based Hy-Vee demonstrates, fresh can also be a portal to a company’s values. For example, customers who shop at the Midwestern chain’s more than 245 stores are assured that the sushi in the retailer’s Nori Sushi bars is 100 percent responsibly sourced as are the many species of fish, mollusks and crustaceans sold in the fresh seafood department, from barramundi to Alaskan king crab legs to oysters. Indeed, Greenpeace ranks Hy-Vee among the top grocery retailers for seafood sustainability. Going the extra mile to ensure quality and safety, Hy-Vee also voluntarily employs a full-time U.S. Department of Commerce seafood inspector at its wholly owned Perishable Distributors of Iowa (PDI) subsidiary in Ankeny, Iowa.

Hy-Vee’s produce department also reflects the company’s commitment to environmental sustainability, specifically food waste reduction. The retailer has earned recognition, including a 2017 award from Store Brands for “Best Store Brand Merchandising Idea,” for the way it champions The Misfits, cosmetically challenged produce supplied by Eden Prairie, Minn.-based Robinson Fresh, which brought the Misfits concept and brand to the United States. (The brand originated with Redhat Co-operative in Alberta, Canada.)

Hy-Vee, which has sold nearly 2 million pounds of the misshapen, off-size or slightly discolored but otherwise delicious fruits and vegetables, “is a good example of a company that has embraced the program holistically, from sustainability to a consistent eating experience,” says Craig Arneson, general manager of Robinson Fresh. “It is paramount to the success of the Misfits program to have collaboration at all levels of the organization.”

Approximately 20 SKUs of The Misfits are available at any time, with the specific choices depending on the season. “Much of the product was left in the field or destroyed in the past, so the Misfits program provides a sustainable outlet for a wider range of production,” Arneson explains. In addition, to reducing waste and providing customers with affordable produce, the program helps support growers financially.

Meeting consumer demand

Winning over shoppers in the fresh realm requires meeting consumer demand for both healthful products and on-the-go convenience, notes Jeff Oberman, vice president of trade relations for the Washington, D.C.-based United Fresh Produce Association. One retailer that excels in this domain is Lowes Foods in Winston-Salem, N.C. The retailer’s stores have a “Pick & Prep” station, allowing shoppers to select their own fresh fruits and vegetables and then drop them off for customized cutting.

“So if you want to purchase a mango but don’t know how to cut it, you can bring it to the Pick & Prep station, and a trained produce professional will cut it for you,” Oberman says. Many customers also use the service to save time while they continue to shop, specifying whether they want an item, be it an onion or a watermelon, diced, sliced or chopped. Consumers can even order this service for produce purchased online from Lowes via Instacart.

Besides convenience, contemporary consumers, especially millennials, are demanding transparency and, when feasible depending on the season and type of product, local sourcing, Oberman points out. “Consumers want to know how these products are produced and how they’re grown. They want to know that the people who harvest the crops are ethically treated,” he says. “And it’s not just with produce; it’s with everything in the store.”

Consumers, moreover, increasingly expect to find organic offerings, but the demand for organic varies widely, depending on the region and shoppers’ income levels.

In southwestern Indiana, for example, where Baesler’s Market operates three stores — in Terre Haute, Linton and Sullivan — shoppers do ask for organic items but demand is not robust, says Bob Baesler, the company’s president. Nevertheless, he maintains a 12-foot section of organic produce in the less-rural Terre Haute store, which is in a small city of approximately 61,000 people.

“We don’t sell a lot of it, but there are people who want it, so we try to have it for them,” Baesler says, noting that Baesler’s Market’s commitment to delighting customers in the fresh arena is one way the retailer differentiates itself from Dollar General, which has several stores in the communities Baesler serves.

In a rural locale with many farms, consumers are more apt to prioritize local sourcing because of the positive impact on the area’s economy; it’s not simply a trendy millennial-driven preference.

Baesler’s Market carries local corn, carrots and watermelons. “We attempt to do as much local as we can, but there is a limit to what we can do,” Baesler says. Not only does Indiana have a limited growing season, but also local producers can’t meet the retailer’s need for many items during the warmer months.

“Outside of the three mentioned items, [local farms] don’t have enough quantity to where we can just depend on them all summer for tomatoes or all summer for cucumbers,” he elaborates. Still, customers appreciate the retailer’s efforts to sell local produce, and Baesler diligently works with the area’s farmers to bring more locally grown items into the three stores. For example, Baesler’s this year partnered with a Terre Haute organic farm called The Pickery, where customers normally go to pick their own vegetables. “On a regular basis, [the owner] would bring us eggplants and other items. But the supply was such that it only lasted a couple of days,” Baesler says.

Local sourcing is a challenge everywhere, and some larger supermarket chains are helping to defray farmers’ production costs to ensure a supply of fresh products that can meet rising consumer demand, Oberman adds.

Though still in the experimental phase and not a solution to the local supply challenge, an emerging trend among grocery retailers is “hyperlocal” store-grown produce. Retailers are beginning to grow their own leafy greens and herbs in rooftop greenhouses, on the sides of stores in hydroponic vertical gardens, and — as H-E-B-owned Central Market is doing — in a mobile container just outside of a store that could be moved from one location to another.

Behind one of Central Market’s Dallas stores, a 53-foot custom-built Growtainer, made from a recycled shipping container, provides 480 square feet of climate-controlled vertical production space. The miniature farm features proprietary technology for ebb-and-flow irrigation, a water-monitoring system, and energy-efficient light-emitting diode (LED) production modules specifically designed for multilayer cultivation, according to Glenn Behrman, president of Dallas-based Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) Advisors, which developed the Growtainer specifically for Central Market.

Behrman points out that the Growtainer has been a highly successful “innovation project” for the retailer. “They can’t keep up with the demand,” he says.

The hydroponically grown leafy greens are merchandised in the store’s produce department on an attractive mobile “Store Grown Produce” display made of wood. The greens are wrapped in plastic with a label branding the product as “Central Market Store Grown Lettuces,” with 10 varieties of lettuce listed and the specific type of lettuce in the package indicated with a checkmark.

For the Growtainer to work, “you need a fast-turnover, shallow-root kind of crop” and substantial commitment from the retailer, Berhman says.

Foraying into fresh-prepared

Addressing customers’ need for convenience and their growing enthusiasm for ethnic foods, grocery retailers across the country are expanding their deli departments into “grocerants,” establishing hot bars, salad bars, signature dishes, made-to-order stations and even fast-casual and full-service restaurants.

Hy-Vee has significantly ramped up its foodservice options at its new Minnesota stores. But smaller chains are also favorably impressing customers with expanded fresh-prepared offerings. For example, since KFC left the area, Baesler’s Market has developed a big fan base for its signature fried chicken, Baesler says.

The Indiana retailer also emphasizes quality and consistency in its deli meats and salads. “Some retailers will switch suppliers, but customers get tired of things not tasting the same,” Baesler notes. “We’ve been selling the same slaw for 20-some years and the same potato salad.”

The company does take risks, though it may tread more cautiously than urban and college town grocers with a younger population base. For example, when the retailer first added a hot bar in 2015, a number of customers complained because they didn’t like the change. But the hot bar has done “exceptionally well in sales,” according to Baesler, who notes that he has expanded the number of soup wells from three to six because soup is so popular with his customers, even during the summer. The hot bar offerings at Baesler’s include Mexican, Italian and Chinese dishes as well as American comfort food such as meatloaf.

Customized convenience seems to be the watchword of another supermarket chain, Skogen’s Festival Foods, which owns 31 stores in Wisconsin. In addition to a rotating hot bar menu featuring BBQ Monday, Taco Tuesday, Stir Fry Wednesday, Italian Thursday and Supper Club Friday, the De Pere, Wis.-based chain offers a “Daily Deli Deal.”

“For instance, on Mondays we offer four large pieces of lasagna and a loaf of Italian bread for $10,” says Lars Batzel, fresh department senior director at Festival Foods. “On Tuesday, we have $6 rotisserie chickens. On Wednesday, we have $5 sushi.”

Festival Foods also provides heat-and-eat prepared meals. Shoppers can choose a protein-based entrée and one or two side dishes at different price points. “These have done very well for us,” Batzel says.

Additionally, the retailer is venturing into own-brand meal kits, which are being rolled out to more than 75 percent of the retailer’s stores. What’s more, Festival Foods is considering adding made-to-order stations at some locations, beyond the well-equipped deli service counters. “There are a lot of logistical and equipment challenges that go into this, so we’re trying to figure out the right approach for us,” Batzel says.

Find a niche

In highly competitive markets, retailers need to find a niche in fresh where they can outshine rivals. This could be a bakery department that is the go-to place for birthday cakes, holiday pastries and even wedding cakes. Or perhaps the bakery is situated near the front of the store so shoppers can enjoy the aroma of fresh-baked bread as they walk in.

The often unsung dairy department also provides opportunities for differentiation, notes Julie Quick, Plano, Texas-based Shoptology’s senior vice president for insights and strategy. Retailers can use sampling to drive trial of flavored milks, newfangled non-dairy milks, new cheeses and yogurts. Supermarkets should also tell the stories of the farms that supply the store brand milk and other products in the dairy case, she suggests.

“Dairy has to actively managed and credentialed as a fresh department,” Quick emphasizes. “Retailers need to work harder to ensure freshness and share the origins of the product. The wholesomeness and goodness of the product needs to be merchandised.”

Consumers are looking for products with protein, so buzz can be built around milk’s naturally high protein content, adds Susan Stege, senior director of category and shopper insights for Dallas-based Dean Foods. Milk is also a natural product, ideal for modern consumers who are gravitating toward less-processed foods, she says, noting that positive dairy messaging can be established through the retailer’s website and social media channels.

As Stege puts it, “You can’t get any more ‘clean label’ than milk.”

Schierhorn, the managing editor of Store Brands, can be reached at cschierhorn@ensembleiq.com.

Box Greens Hydroponics Brings Farm-In-A-Box Concept To Miami

WENDY RHODES | October 29, 2018

Imagine growing 500 heads of lettuce every week in a space smaller than your backyard. That's what sisters Lisa Merkle and Cheryl Arnold of Box Greens are doing with hydroponics.

But instead of growing greens inside stationary buildings like most hydroponic farmers do, they use portable 40-by-eight-foot shipping containers that can be placed near where the produce will be consumed.

“Climate change is a major issue, and one of the main contributors is CO2 from transporting food,” Merkle says. “Most of the produce we eat comes from very far away, like Chile, South Africa, and New Zealand. Most of the lettuce at Whole Foods comes from California.”

Box Greens is a Miami-based company that retrofits shipping containers into portable hydroponic farms that grow non-GMO produce using sustainable, environmentally friendly methods with no pesticides or herbicides.

“We have the ability to grow an abundance of fresh, nutrient-dense food without an impact on the environment like traditional produce,” Merkle says of the company’s hydroponic, farm-in-a-box concept.

“It’s really surprising because we live in one of the most beautiful and lush places, but there are very few things we eat regularly that are actually grown in South Florida,” Merkle says. “Produce is picked before it's ripe, then it sits in containers for weeks or months where it’s sprayed with gases to preserve it."

Each container produces the equivalent of 1.5 acres of land, and Merkle says that herbs, microgreens, lettuces, kale, and collards flourish the best in hydroponic environments. Unlike traditional soil farming, hydroponics use no dirt. Nutrients are injected into the plant’s root systems through the water.

“With climate change, there is not the ability to farm like people used to, but the idea of bringing farming indoors allows production 365 days a year,” Merkle says. “And that’s groundbreaking.”

Nutrients from soil are critical to optimal health, and Merkle says that while hydroponics are healthy, they are best consumed in conjunction with traditionally farmed produce. But hydroponics can help us avoid the problems associated with long-distance food transport.

“We can’t live in a bubble just growing hydroponics under lights with filtered water and nutrients,” she says. “The future of food is eating hydroponics and things that are locally grown.”

Box Greens expects to have its first containers producing by December. The containers can be placed in schools to teach children about nutrition and urban farming, or near restaurants to provide greens so fresh that they can be consumed the same day they are picked.

Merkle also hopes to place containers in some of Miami’s food deserts where people have little access to fresh produce.

“We will give on-the-job training,” she says about hiring locals to learn about hydroponic farming. “We pay fair wages and will host onsite community dinners to bring together the community in public places where people can learn about healthier eating.”

Wendy Rhodes is a lover of rock 'n' roll and all things vegan. She has witnessed a green flash, kissed a live shark, and stood atop an active volcano. She is always open to new story ideas.

Kimbal Musk Is Reinventing Food One Shipping Container At A Time

Interesting dresser, marketing pro, rich dude, brother to the most famous man in tech: Musk is changing food production, one shipping container at a time. And it's starting to work.

By Kevin Dupzyk

Oct 24, 2018

DAVID SCOTT HOLLOWAY

The low-slung building on Evans Avenue with the greenhouse roof blends into the surroundings in an uninspiring stretch of Denver, all nondescript retail and pockets of ranch homes. It’s a hydroponic farm, run by partners Jake Olson and Lauren Brettschneider. The produce is all on tables at waist height, and the plumbing is subtle and minimalist. There is no soil anywhere. From the street it’s easy to miss Rebel Farm; inside, it looks like an Apple Store hosting a farmer’s market.

One afternoon this summer, Kimbal Musk, a tall, lanky man in a cowboy hat, ducked in through the front door. He was here to see about the produce for his Denver-area restaurants. Unlike, perhaps, the average restaurateur, he’d brought a couple of assistants, who used smartphones to photograph his entrance, and his greeting with Olson and Brettschneider, and the huge smile he put on when he surveyed the farm. He’d never been to Rebel Farm before, but the operation was already providing him gem lettuce, a trendy green, and now he wanted to see what else it might offer. Olson and Brettschneider start walking him up and down the aisles. The building’s southern exposure is a heat-exchanging wall, and they start there, in the cool-climate crops.

“We just can’t get spinach to grow,” the Rebel guys say.

“Really?” Musk asks. “What about kale?”

Arugula’s easy. “The gateway green,” they all agree.

Musk surveys the farm and talks hydroponic technology in the manner you expect his older brother, Elon Musk, might approach a tour of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Like his brother, Musk is a billionaire entrepreneur, but since 2004 he’s made his living in food.

Musk tastes hydroponically-grown greens at Rebel Farm, an urban farm in Denver, CO.

DAVID SCOTT HOLLOWAY

At each new crop, Olson and Brettschneider tear off a few leaves for Musk to try, and he takes each bouquet, contemplates it, smells it deeply, eyes closed, takes a bite, and stares off into the middle distance. For a moment it’s like he is absorbing the simple life of the leaf, just sun, soil, and water, the way cannibals eat the hearts of others to imbibe their essence.

Of course, this also makes for good photos. And Instagram Live opportunities. He asks Olson and Brettschneider to do a short live video with him, and they oblige him behind a planting of sunflower sprouts on a sheet of geometric growing foam called Horticubes. An assistant gets in position with her smartphone, and as soon as they start recording, Musk comes to life, a perfect host, asking leading questions and making sure that the brands’ audience gets to know Olson and Brettschneider and their strange urban farm of delicious hydroponic crops.

Video over, tour back on, and Musk quickly turns to logistics. “Do you know how much production you do?” he asks.

Musk has a particular interest in this farm that goes beyond his restaurant chains, The Kitchen and Next Door. Musk also cofounded an urban farming startup based in Brooklyn, called Square Roots. Square Roots develops hydroponic farms housed in shipping containers that use high-tech lighting systems and offer precise, scientific control of light and every other relevant variable, like water and nutrients. Then it teaches a new breed of farmer—think Brooklyn hipster with a back-to-the-land mentality—to use them.

“Well, this is 15,000 square feet,” says Olson.

“Right, so that’s about one third of an acre,” Musk says. “At Square Roots we’re able to take a shipping container and get two acres of productivity out of it.”

“That’s some big shipping container,” Brettschneider says, not quite getting what Musk’s driving at. Musk is speaking entrepreneur, but Olson and Brettschneider are just two people who left pretty good day jobs to work the land. (As it were.)

Sprouts on a low-water growth medium. DAVID SCOTT HOLLOWAY

Musk’s goal isn’t just to produce food, or just to produce food that’s good. It’s to produce what he calls “real food”—“food you can trust to nourish your body, trust to nourish the farm, and trust to nourish the planet”—as efficiently as possible. The way he sees it, the last few decades have seen two food movements, opposites, both misguided. There’s the precious food movement, which aims to set the table only with food grown in the immediate community. The problem with that is that it’s pretty much restricted to wealthy people in fertile places.

Then there’s the feed-the-world movement, which produces more food than we need, most of it processed, unhealthy, and untasty, leading to health problems like diabetes and obesity. Musk is trying to shoot the gap, and unlike the cornucopia of restaurateurs in most midsize or larger cities these days offering local kale, he has the background and resources to implement a grander vision. Kimbal opened The Kitchen, a fine-dining restaurant, in 2004 before conceiving of Next Door, which sources ingredients with the same principles but offers food with a tad less pretention and a bit more fun, at prices—generally under $15 an entrée—that most Americans can afford. And Musk has ancillary enterprises that lay the groundwork. He founded a nonprofit, Big Green, that installs learning gardens in schools to educate kids about real food. Then there’s Square Roots. Musk points out that with shipping-container farms, which lock out all the traditional encumbrances of farming—drought, locusts, 24-hour cycles of day and night—optimization of food is possible. Unlike a traditional farmer, who may work his land for 50 years and in that time get only 50 growing seasons to experiment with, a Square Roots farmer can iterate endlessly until: spinach.

As we’re getting ready to leave, Olson and Brettschneider ask if they can show off some of their more specialized crops, and we make our way to the hot north end of the farm. They take us to a rack covered with huge serrated leaves and tangles of thick stalks. Brettschneider pulls some of the tangle away and points at a smooth purple ball from which the stalks emanate.

“What is that?!” Musk asks.

“Kohlrabi!” Olson says, uprooting one and handing it to Musk, who holds it in one of his big hands and examines it from every side. Olson launches a disquisition on all the ways you can cook up kohlrabi, and while Brettschneider says it isn’t exactly her favorite veggie, even she’s clearly pleased to be showing off their crop. Musk smiles, pondering all the uses of this strange orb, and his assistants fire up the smartphones to catch him mugging with the vegetable.

“It’s a pretty good job I have,” Musk told me earlier that day, on the way into a shopping center in a neighborhood in South Denver. “I get to go drop off food at children’s hospitals.”

Just across the street is a branch of Children’s Hospital Colorado, and we’ll be heading there soon—just as soon as we finish at this shopping center, where we’re checking out what will soon be the newest Next Door. So far it’s a plywood husk. The whole time Musk walks around the interior, he’s being photographed. He throws on a hard hat and walks slowly from room to room, exaggerating looks of surprise. The check-in is as much photo op as inspection, part of the constant hard work of building a business.

I ask him if he ever gets tired of being photographed. “Oh, with Instagram, it’s all the time,” he says, in a way that might be wistful if one could be wistful through such a radiant smile. “Not just journalists.”

DAVID SCOTT HOLLOWAY

When every conceivable angle has been captured for social, he says—cheerfully—“Let’s go meet the neighbors!” When Musk opens a new location, he likes to scout the other businesses nearby. The shopping center is a quad, with rows of stores around each of four sides. We skip the eyelash store next door to Next Door, which isn’t open yet, and go into a clothing boutique one storefront down.

Musk asks the woman behind the counter at the boutique how long they’ve been open, and how things have been going, and which tenants are in already. You know—small talk. This is the thing about Musk: Everything he does has a purpose.

The woman mentions the parking situation, which is that there isn’t enough of it. “Yes,” Musk says. “I did notice that it seems like not quite enough spaces for the businesses here.” He looks out the glass walls of the boutique, a little troubled. We proceed to the Orangetheory Fitness on the adjacent side of the quad. Musk mentions the parking, and the young man and woman working agree that, yes, it really does seem like there are a lot of cars here. Musk peeks into the last two stores on that side of the lot and then works his way back to a Starbucks on the far corner, popping his head into more shops along the way. He eyes the full lot suspiciously as he walks, first on the way into the Starbucks, and again on the way back out, cup in hand.

When we finally climb through gull-wing doors into the backseat of a white Tesla Model X, Musk looks around for a moment before pushing a button on the back of the center console to release two cup holders.

“Have you given your input into the design of the cars?” I ask. (Musk serves on Tesla’s board of directors.)

“Oh yes, I’ve been quite involved,” he says. “Once there was a design with no consideration of cup holders. That was a terrible idea.”

In 1999 Kimbal and Elon sold Zip2, the company they cofounded, to Compaq for $307 million. Elon took his and became Tony Stark; Kimbal took his and moved to New York, where he enrolled at the French Culinary Institute. He was living blocks from the World Trade Center on 9/11—close enough that he had a security pass to get into the zone around the Twin Towers that shut down for rescue and cleanup. That’s the first of the foundational stories about Musk and food: that he used that pass and the good suggestion of a Culinary Institute colleague to spend weeks feeding firefighters at Ground Zero. He opened The Kitchen in Boulder three years later. The second foundational story about Musk and food happened in 2010. At the time, Musk was still working for tech companies in addition to working in food. He was tubing in the snow with his family when his tube flipped and he broke his neck. He was paralyzed for three days, and found himself contemplating all the big things one contemplates in such circumstances. It was time to get out of tech, he realized. Food was his passion.

As we pull out of our parking space, he asks his assistant, who’s driving, to exit the shopping center between a Shake Shack and a Torchy’s Tacos, a different way than we came in. He doesn’t know Torchy’s but he’s heard it’s popular. He gets a call as we’re leaving. “The problem with this place is going to be the parking,” he says into the phone. He bobs his head down to look at the patios of the Shake Shack and the Torchy’s, which are both full of customers, and registers approval.

Musk’s finishing up the call when we pull into the parking lot at the children’s hospital. On the way in, he shakes a few hands and takes more pictures. We wind our way back to a conference room, where Hal Reynolds, Next Door’s regional operations manager, and Brad DeFurio, development chef, are rotating in fresh trays of roasted veggie quinoa bowls, ancho chile chicken bowls, curry chicken sliders, and chips and guac and hummus for hospital staff. Musk greets Colin Ness, director of operations: Parking is going to be a problem, he tells him. Musk does more photos and a TV spot and grabs some food. I ask him what he recommends. He assures me that it’s all good.

THIS IS THE THING ABOUT MUSK: EVERYTHING HE DOES HAS A PURPOSE.

“This is really great for us,” he says, pausing to chew. I expect something about what fighters the kids are, and how pleased he is to have such an admirable neighbor. Instead: “Because we’re trying to add catering, and this is a good test.”

Musk never lost the skills he honed at Zip2 and the other tech companies he worked for. At Zip2, he was director of product marketing, and he tells me he’s still a product guy at heart. He figures out what he’s selling and how to position it. He makes himself an embodiment of the brand, which these days is about food and connection. When Kimbal Musk wants to reconnoiter a shopping center, he says, “Let’s go meet the neighbors!” When he needs a test run for catering, he finds a children’s hospital.

That night Musk works the open-air upper level at Next Door Glendale, a location in another corner of suburban Denver. Next Door hosts a school fundraiser series called 504U: On certain nights, when a school brings in business to the restaurant, they get to keep 50 percent of the profit. Tonight is the pre-school-year event to rev up the educators for another season of philanthropy. Musk goes from group to group of buzzed teachers and gorged administrators and expertly makes conversation and offers hugs.

Then Ness comes over and speaks to him semiprivately, voice a hush. Musk’s eyes grow wide with amusement, and he puts his hands over his mouth. From the looks of things, some part of tonight’s itinerary has gone wrong. Musk and Ness whisper, and then Musk shrugs, and Ness dashes off to fix it. Musk goes back to work. He greets everyone like he knows them. He’s mixing and greeting and good-humoring—even when a guest, like the fanboy wearing a ball cap emblazoned with “The Boring Company,” the name of one of the many projects of Musk’s brother, doesn’t seem so interested in the fundraising as in a real-life audience with a Musk.

Soon Reynolds comes walking slowly and carefully through the crowd, gingerly carrying a bucket and some kind of cloth-covered implement, which radiates heat. Ness follows, and he gets Musk’s attention. Musk jumps up on a chair and draws in the crowd. “We call this a branding party,” he says. “And we’re going to take an actual brand, like you’d use on an animal, and put a brand on the restaurant.”

“The catch is,” he says, “the handles burned off.”

MUSK GOES FROM GROUP TO GROUP OF BUZZED TEACHERS AND GORGED ADMINISTRATORS AND EXPERTLY MAKES CONVERSATION.

Musk hops down from the chair and walks over to the bucket. The charred remnants of the brand’s dual wooden handles have been wrapped in a few layers of towel and tied fast with string. What wouldn’t Elon give to fix a problem so easily? It’s not a bad gig Kimbal’s got, having expressed the Musk curiosity and faith in technology through a product that still has the most visceral, tangible kind of accountability—Does it taste good?—and now he’s got these restaurants and he’s teaching children to eat well and he’s pursuing his own dream of a previously unimaginable future, one in which a trendy city kid says “Welcome to my farm!” and cranks open the door of a shipping container in some gritty, hollowed-out urban district and runs his hands through hanging fields of chard.

Musk grabs the towel handles with both hands and presses the brand hard into the wood frame of a large chalkboard menu hanging on the restaurant’s wall. He splays his great long legs wide to form a base of support and pushes hard. At first, nothing seems to be happening, and Musk is straining, long arms taut. Then you start to smell it. Wood. Wood burning. Musk’s body quivers with the effort. It’s been a long day. Smoke starts to rise from the brand and the smell intensifies, that burning wood smell of chips in charcoal. Musk holds the brand in place a second longer, then pulls back. A perfect “ND” is burned into the wood. “Ha!!” he shouts. He lets loose a primal scream. He smiles a big, toothy smile. He’s made his mark.

Musk has made his mark.

DAVID SCOTT HOLLOWAY

The next morning, Kimbal invited me and David Scott Holloway, a photographer, to hike his commute: from his home in a Boulder neighborhood, up the side of Mount Sanitas, and back down to the original Kitchen and Next Door in downtown Boulder.

Looking east from just above the treetops of Kimbal’s neighborhood.

Kevin Dupzyk: So Square Roots attacks the farming problem with technology. Do you think of Square Roots as more of a technology company or a food company?Kimbal Musk: I think it’s not a meaningful distinction. In order to do anything great today, you have to be a technology company. But on the food side, you’ve got to grow something that tastes great and is super-nourishing. That people trust. If they don’t like it, they don’t like it. You can’t solve a product-quality problem by talking about the technology.

KD: You said yesterday that even when you were doing tech stuff, the marketing thing was what you were really good at. Where did that come from?