Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Farming Food In A Freight Container

An old shipping container arrived on campus last fall. From the outside, it was an innocuous-looking, beige structure that might have fallen out of the sky. The inside, however, contains one of the most innovative farming systems in the world

An old shipping container arrived on campus last fall. From the outside, it was an innocuous-looking, beige structure that might have fallen out of the sky. The inside, however, contains one of the most innovative farming systems in the world.

The shipping container is what is called a freight farm. Produced by Freight Farms, a company founded in 2010 and headquartered in Boston, the container is 320 square feet and contains an advanced hydroponic growing system, meaning that its plants are grown in a mineral nutrient mix instead of soil. The King’s freight farm was installed behind Atair House in November and subsequently painted by students from the Middle School.

The goal of the freight farm is to maximize food production while minimizing water use and the distance between the farm and the site of consumption. At capacity, the freight farm can grow 3,000-5,000 maturing plants simultaneously — the same amount of food that could be grown on two acres of farmland. Yet the farm uses fewer than 10 gallons of water per day, a reduction of about 90 percent, according to Freight Farms Client Services Director David Harris.

Called the Leafy Green Machine by Freight Farms, the unit produces greens for the Dining Hall. “Right now, it’s producing spinach, kale, chard, and romaine,” says Director of Operations Ola Bseiso. While capable of growing other types of vegetables, the Leafy Green Machine is designed specifically to produce greens. And thanks to a staggered schedule, the farm will yield fresh greens every day.

Seeds are first placed under light for two weeks until they become sprouts. Then, during the seedling stage, the plants grow deep roots and begin to show leaves, taking three weeks to fully mature.

When mature, the vegetables are harvested in the morning and placed in the Dining Hall for consumption in the afternoon.

The freight farm’s lettuce will pair nicely with the surrounding crops. “On one side of the freight farm, there is a large fruit tree section — apples, peaches, and other fruits,” says Bseiso. “And to the left are around 25 soil beds with various plants. And the best part is: it’s all organic!”

Beyond its beneficial nutritional and environmental effects, the freight farm offers ample opportunities for learning.

“You can see the entire process of plant growth happening, from the seedling all the way to harvest,” says Harris.

Dima Kayed, head of the Physical and Life Sciences, says that teachers of chemistry and biology intend to incorporate the freight farm into their classes, including looking at the dynamics of plant growth, types of plants, lighting, testing water quality, and other elements.

In addition, the trajectory of Freight Farms offers a case study for entrepreneurial students: eight years ago, the freight farm was only an idea, and now it is a full-fledged, successful product with a presence in nearly 20 countries.

Harris is hopeful that King’s students will gravitate to the freight farm. “You should care where your food comes from, as it doesn’t just appear on your table or plate,” he says. “There’s an entire industry built around it. Students can now understand the food system from a sheltered, air-conditioned box.”

But it’s not just about looking at the food; it’s about eating it. So if you find yourself in the Dining Hall, grab some lettuce from the salad bar, because odds are it’s the freshest salad you will ever eat.

Indoor Farm Started In A Shipping Container

The Gruger Family Fungi farm has come a long way since its beginning in a metal shipping container. Today the mushroom farm is in a warehouse in an oilfield industrial park

September 26, 2019

Rachel Yadlowski shows some of the mushrooms grown in her family’s indoor farm. | Mary MacArthur photo

An Alberta family’s mushroom operation sells its produce to wholesale markets, restaurants, hotels and specialty stores

NISKU, Alta. — The Gruger Family Fungi farm has come a long way since its beginning in a metal shipping container. Today the mushroom farm is in a warehouse in an oilfield industrial park.

There may not be soil, gravel roads and quarter sections of land, but Rachel Yadlowski believes their warehouse bay is a new kind of farming.

“We are farming in a warehouse. It’s an indoor farm,” said Yadlowski, who operates the farm along with her husband, Carleton Gruger, and other family members.

“It’s a different kind of farming. It’s a different way of producing nutrition all year around.”

This farm doesn’t grow just one crop, it grows a colorful collection of tree-loving mushrooms few people have heard of, seen, or eaten.

The pink oyster mushroom has a subtle bacon flavor, while the blue oyster becomes soft and velvety when cooked. The gold oyster has “fruity notes” and the king oyster is nutty and cashew-like. The lion’s mane mushroom looks like cauliflower and tastes like lobster.

And those are just the eating mushrooms. The family grows reishi and codyceps for tinctures and creams sold for their health benefits.

For hundreds of years, mushrooms have been an important part of people’s diet as a source of protein and healing powers. Yadlowski wants to bring mushrooms back as an important part of our diet.

“We’ve lost our mushroom knowledge.”

Yadlowski has been making converts from her farmers market table and now from the grocery store promotion booth since the family fungi business started in 2015. When customers look at the strangely shaped fungi, they’re worried the mushrooms she sells are not safe to eat, or are just too strange to eat.

Almost half of their customers are vegan, buying mushrooms for their high level of protein. A growing number of chefs and home cooks want to incorporate the unique flavoured mushroom into foods. The mushrooms are now sold through wholesale markets, restaurants, hotels and specialty stores.

The process of raising mushrooms begins in the laboratory with spores grown in a petri dish.

“This is where we’re cultivating the seed for our fungi farm.”

The spores are added to jars of sugar water and then splashed into a bag of warm wheat grain to grow and expand. That bag is added to a mixture of hemp herd, hemp heart screens and mash from the nearby Rig Hand Distillery.

“It’s all nutrition for our mushrooms.”

The mycelium-rich mixture is mixed together in the mushroom mash mixing machine before it’s heated, cooled and squished into long, plastic-shaped logs and hung in one of 13 climate-controlled growing rooms.

Pink, blue and gold oyster mushrooms grow on artificial logs in special climate controlled rooms. | Mary MacArthur photo

“We are creating artificial logs.”

In two weeks the pink, gold and blue mushrooms are poking out of the bags and picking begins. It takes about three weeks before the king oyster mushrooms can be harvested.

“Keeping the rhythm on our farm is important. We always have to make sure there is good rotation.”

In 2017, growing mushrooms was still a hobby, but the demand by restaurants for a more regular supply of unique mushrooms pushed the family to jump into mushroom production on a larger scale. The first harvest at their Nisku farm was March 2018 and with more demand and improved processes, they can double production on their farm at the same location.

When the mushroom growth in the rooms slows down, the logs still filled with thousands of mycelium are sold to home gardeners, spread onto soil and the mushroom growing continues in the backyard.

“Mushrooms give back that life and invite more micro-organisms back to the soil.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mary MacArthur's recent articles

Farm puts out welcome mat for trees September 19, 2019

Alberta greenhouse closure sign of a tough business September 12, 2019

Bowery Farming's Irving Fain Pens Essay On Need For 'Scalable Solutions' In Food Production

"When I founded Bowery Farming in 2015, vertical farming certainly wasn’t new. But to many, the concept as an answer to feeding a hungry planet was far more a dream than a reality

Bowery Farming's Irving Fain | Photo courtesy of Bowery Farming

Fain, the company's founder, says Bowery and other indoor farmers have to improve but are taking the right steps, in helping to combat climate change.

In an essay posted by Bowery Farming's Medium page, company founder and CEO wrote about climate change during 2019's 'Climate Week' and noted indoor farming's role in combating climate change.

"When I founded Bowery Farming in 2015, vertical farming certainly wasn’t new. But to many, the concept as an answer to feeding a hungry planet was far more a dream than a reality. However, here we are, just four years later, and Bowery has two fully operational farms and more in development," Fain wrote. "Our controlled indoor growing environment enables us to use zero pesticides and 95% less water to grow fresh produce — all of which make it on local store shelves within just a few days of harvest, minimizing food miles and extending shelf life to reduce food waste."

Related story: Bowery Farming's Irving Fain on technology, food safety, and new products.

"However, on the first day of Climate Week, I acknowledge that indoor vertical farming still has a way to go. Our sector is in its infancy, and we too have work to do in curbing our own emissions, investing in alternative energy sources, moving away from plastic packaging, and selling beyond just leafy greens. Fortunately, these are all areas that we’re aggressively making progress toward at Bowery. We have seen meaningful gains on many of these fronts already, and I am not dissuaded by the work ahead; in fact, I’m energized by the opportunities that are still in front of us. Today, our effort is now recognized as a scalable solution tailored to our most pressing problems."

You can read Fain's full post by clicking here.

Vertical farms Urban agriculture Technology

VIDEO: What Is Vertical Farming? And What Are The Benefits?

Higher yields, fresher food, smaller carbon footprint: This is the potential of vertical farming.

World Economic Forum

Higher yields, fresher food, smaller carbon footprint: This is the potential of vertical farming.

Read more about the inspiring pioneers finding creative solutions to climate catastrophe here:

https://wef.ch/pioneersforourplanet

About the series:

Each week we’ll bring you a new video story about the people striving to restore nature and fighting climate change. In collaboration with @WWF and the team behind the Netflix documentary #OurPlanet. #ShareOurPlanet

Want to raise your #VoiceForThePlanet? Life on Earth is under threat, but you can help. People around the world are raising their voice in support of urgent action. Add yours now at www.voicefortheplanet.org

Founders Brewing Executive Named CEO of West Michigan Hydroponics Farm

John Green, who for more than a decade served as executive chairman of Founders Brewing Co., has been named CEO of Revolution Farms, an indoor hydroponic farm based in Caledonia that grows lettuce and salad greens

September 17, 2019

John Green has been named CEO of Revolution Farms. (Courtesy photo)

By Brian McVicar | bmcvicar@mlive.com

CALEDONIA, MI — John Green, who for more than a decade served as executive chairman of Founders Brewing Co., has been named CEO of Revolution Farms, an indoor hydroponic farm based in Caledonia that grows lettuce and salad greens.

Green is a founding investor in the farm and has served as acting CEO for the past three months, according to a news release. He is also chairman of its board of directors.

“We launched Revolution Farms to change the world by changing the way we grow food," he said in a statement. “Our revolution begins at home, by growing closer to where we live, more sustainably, with less water and land, and figuring out how to accomplish this in Michigan all year long.”

Revolution Farms has the capacity to produce more than 500,000 pounds of lettuce and salad greens on a yearly basis at its 85,000-square-foot indoor farm on 76th Street in Caledonia, the company says. Its products are sold at Family Fare, D&W Fresh Market and VG’s Grocery stores across Michigan.

West Michigan company's innovative salad greens now on store shelves

Revolution Farms is selling its product in 16 SpartanNash stores in Michigan.

The farm grows its products using 95 percent fewer acres and 90 percent less water than traditional farming methods, Green said. Its salad greens can be shipped to stores in one or two days, “less than half the time it takes for lettuce grown and shipped from California, Arizona, and Mexico to make it to Michigan store shelves.”

Green has worked at Founders since 2006. He will remain at the brewery while its majority ownership transitions to Spanish brewing conglomerate Mahou San Miguel. Founders announced late last month it was selling a 59 percent ownership stake in the company to Mahou.

The deal is expected to close next year and was valued at $198.8 million, according to documents filed with the Michigan Liquor Control Commission. Once completed, the deal will boost Mahou’s ownership of Founders to 90 percent. Mahou purchased a 30 percent ownership stake in Founders in 2014.

Green is among a group of Founders shareholders selling their stake in the company to Mahou. Records submitted by Founders to the liquor control commission show Green owned an 8.03 percent stake in the company. In addition, members of his family-owned an 8.36 percent stake in Founders.

In addition to his position at Revolution Farms, Green will maintain roles with Odyssey Media Group and Cirkul.

He also serves as director of the Grand Valley State University Foundation and is a founding board member of Grand Rapids Whitewater. Green also sits on the board of directors for the Grand Rapids Downtown Market.

In addition to Family Fare and other SpartanNash grocery stores, Revolution Farms sells its products through Doorganics, an organic grocery delivery service based in Grand Rapids, and Van Eerden Food Service.

Colorado: Urban Farm, Restaurant And Market Coming To Englewood

Behind that glass window will reside a hydroponic system where plants will grow on indoor towers. Hydroponics is a method of growing plants year-round in sand, gravel or liquid with added nutrients without using soil. Farms that use the hydroponic method use up to 10 times less water than traditional farms, according to the National Park Service

Grow + Gather Will Occupy The Old Bill's Auto Service Building

Monday, September 16, 2019

Joseph Rios

jrios@coloradocommunitymedia.com

George Gastis sold his tech business four years ago — a year after he packed his bags and moved to Englewood from Platt Park. Contemplating what his next move would be, he knew he always had a green thumb and a love for food.

At first, he had planned to find a property to purchase or rent where he would grow food that would be sold to grocery stores and restaurants. In the process of planning his next steps, Gastis purchased the old Bill's Auto Service building, located at 900 E. Hampden Ave.

“The idea quickly became more than just a place to grow food. There seemed to be a great opportunity to create a place where not only can we grow food, but reconnect the neighborhood and surrounding communities,” said Gastis, referring to places like Littleton, south Denver, Greenwood Village and other areas near Englewood. “Our geographic location is sort of strangely unique in the sense that we sit on the edge of some of those communities.”

After planning and talking to people from his past, Gastis realized there was an opportunity to create a hub around food at the old Bill's Auto Service building. Gastis seized the opportunity, and depending on construction, Grow + Gather will open its doors in October. The development will be a casual restaurant and a market that'll sell coffee and freshly harvested produce and foods - all grown at Grow + Gather.

“When we moved to this neighborhood, I saw the potential in this area. There wasn't a ton to do,” said Gastis. “Combined with trying to figure out what I wanted to do and recognizing the opportunity here — Englewood seemed to be in the process of reviving itself with a lot of new businesses moving in, a lot of development, certainly (Swedish Medical Center) and their role they played in the community — it seemed really interesting.”

The restaurant will be operated by chefs like Caleb Phillips, a Tennessee native who plans to bring a Southern twist to some of Grow + Gather's dishes. Phillips says the menu will be simple, but it'll center around ingredients that will come from Grow + Gather's farm. Some of its dishes will include biscuits, salads, pies, egg dishes, and grits. Beer will also be available at the restaurant, brewed from the second level of the building.

“It's just the neatest idea. I get to walk 20 yards to get fresh vegetables,” said Phillips. “The community has already been super kind and receptive. I think it's going to be a lot of fun.”

When customers walk through Grow + Gather's community room, an area designated for guests to have coffee and for classes on gardening and cooking, they'll be able to see their food being grown behind a glass window. Behind that glass window will reside a hydroponic system where plants will grow on indoor towers. Hydroponics is a method of growing plants year-round in sand, gravel or liquid with added nutrients without using soil. Farms that use the hydroponic method use up to 10 times less water than traditional farms, according to the National Park Service.

Gastis says the rooftop of the building will serve as rooftop greenhouse, where he'll grow crops like tomatoes.

“It is exciting to see a new business concept like Grow + Gather here in Englewood as well as the repurposing of the property once occupied by Bill's Auto Service. It is sure to bring new life to that area,” said David Carroll, executive director of the Greater Englewood Chamber of Commerce. The chamber works to promote its business members while engaging with new businesses in the city.

PHOTOS: COURTESY OF GEORGE GASTIS

A New Hydroponic Farm Starts A New Age For UAE farmers

A new hydroponic farm is under construction in Abu Dhabi, UAE, and it will be one of the most important model projects of Kingpeng in Abu Dhabi

A new hydroponic farm is under construction in Abu Dhabi, UAE, and it will be one of the most important model projects of Kingpeng in Abu Dhabi. The total project is 1.2 hectares and will grow leafy vegetables and fruit vegetables with hydroponic technology. This project has a leafy vegetables NFT system and hanging gutter growing system.

The owner of this project has more than 5 years of organic food growing experience and organic food production certificate. Now he will start a hydroponic farm; all products will be purchased by high-standard hotels and restaurants in the future. Meanwhile, the owner of the greenhouse will establish a new brand for his green vegetables. The idea is for it to be very famous in the market of UAE and around Gulf countries.

“Three years ago, I have visited a lot of farms with greenhouse projects in UAE, but it seems that there are not many high-standard hydroponics farms which can provide what the market wants. So, I visited Kingpeng in 2018 and we confirmed the design and project soon after several meetings. Now in UAE, my project is still on the top level and we will be one of the biggest green vegetable suppliers in Abu Dhabi after the project’s completion and we will expand the production scale soon next year”, said the owner of the greenhouse.

“We really thank Kingpeng for the good service and products and we believe it will not only be a perfect vegetable production base for me but also start a new age for UAE farmers because they will have a better choice.”

Kingpeng has been active in the Middle East for more than 12 years, and they provide one-stop service, full greenhouse solutions and also growing services for the customers after project completion.

For more information:

Beijing Kingpeng International Agriculture Corporation

7th floor, Advanced Material Building, Feng Hui Zhong Lu, Haidian District, Beijing, China, 100094

T: +86 58711536

F: +86 58711560

info@chinakingpeng.com

www.kingpengintl.com

Publication date: Thu, 26 Sep 2019

Singapore Airlines, One of The Most Ritzy Airlines In The World, Is Partnering With A High-Tech Urban Farm

AeroFarms, the company supplying the greens, is a high-tech "vertical farm," which uses a controlled climate, LED lights, and a new type of farming called aeroponics to grow crops in reclaimed urban spaces

Singapore Airlines, one of the most ritzy airlines in the world, is partnering with a high-tech urban farm to make sure it serves the best meal on every flight. Take a look inside the futuristic operation.

September 17, 2019

David Slotnick/Business Insider

Singapore Airlines is about to launch a new "farm-to-plane" dining program, using vegetables grown at a local farm in Newark, New Jersey, in dishes on board its flights from the New York City area.

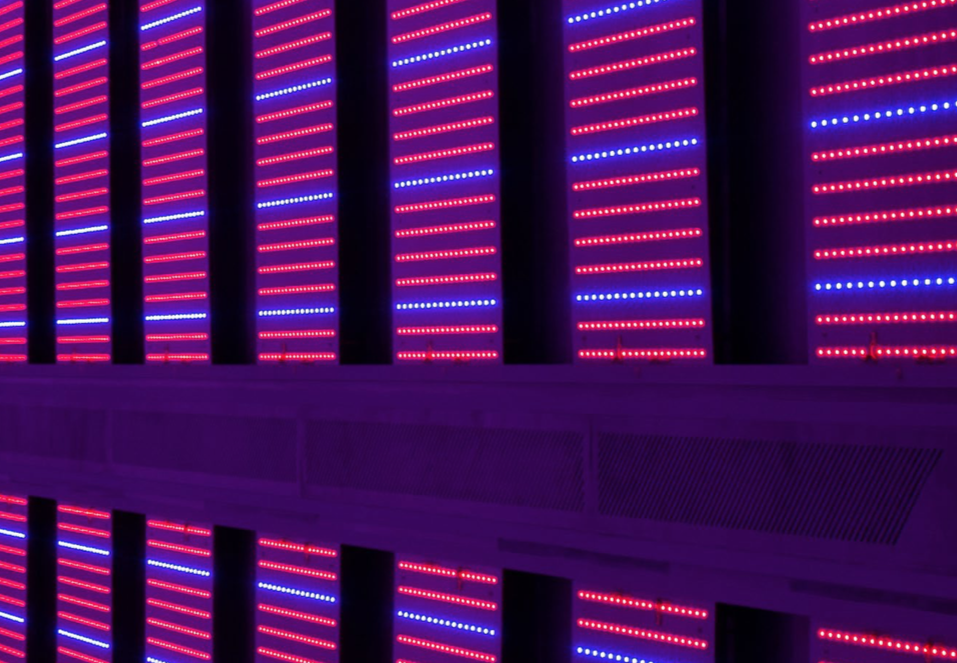

AeroFarms, the company supplying the greens, is a high-tech "vertical farm," which uses a controlled climate, LED lights, and a new type of farming called aeroponics to grow crops in reclaimed urban spaces.

Business Insider toured the AeroFarms facility to learn more about how the process works, and how things like baby kale and watercress can go from the farm to 35,000 feet in just a few short hours. Scroll down to walk through this unique urban farm.

What's the deal with airplane food?

If Singapore Airlines has anything to say about it, that classic stand-up joke will soon be a thing of the past.

The airline made headlines in 2017 when it announced a new "farm-to-plane" dining service coming to its long-haul flights, and again this spring when it announced its first sourcing partner.

Now, the locally-sourced, fine-dining initiative is about to launch on the world's longest flight.

After months of planning and preparation, the farm-to-plane service is kicking off next month on the airline's flight between the New York City-area Newark airport and Singapore.

The airline will work with AeroFarms, a unique indoor vertical farming company based in Newark, New Jersey, to source leafy greens and vegetables for several of the appetizers in its business class cabin starting in October. Meals made with the local greens will eventually be expanded to other courses and other cabins — the plane operating the flight is entirely business class and premium economy.

While the novelty of the "farm-to-table" concept in the sky, coupled with the fresh taste of the meals has an obvious appeal, the airline also touts the sustainability of both sourcing ingredients locally, and supporting eco-efficient businesses like AeroFarms with its business. It could be easy to dismiss that — the airline, after all, is an airline, and relies on fossil fuels to fly emission-generating planes around the world — but there's a twofold benefit that sourcing crops from a company like AeroFarms can provide.

Normally, while catering in the winter, "the greens for our flights from Newark had to be flown in from 3,000 miles away, from California, Mexico, or Florida," said James Boyd, Singapore's head of US communications. "This allows us to instead source our greens from less than five miles away, cutting down on shipping waste."

Additionally, Singapore is looking to expand the farm-to-plane initiative with similar sustainable urban farms around the world, giving a boost to growing eco-friendly businesses — for instance, AeroFarms, which said it plans to add more facilities, is a certified B-Corp, a designation given to businesses that meet certain environmental and ethical standards.

Business Insider recently toured the AeroFarms facility at Newark to see how everything works. Take a look below for our walkthrough of the facility, and the process of getting the greens from the farm to the skies.

Welcome to AeroFarms.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

This high-tech, the one-acre vertical farm can be found at an old steel plant in Newark, New Jersey.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

The farm grows a variety of leafy greens and vegetables that will be used in dishes prepared by Singapore Airlines for its flight from Newark Airport to Singapore — the longest flight in the world.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

Despite its small one-acre footprint, the farm can grow roughly 390 times as much output as a normal farm with the same acreage.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

That incredible output isn't just because the crops are grown on trays stacked to the ceiling — it's because of a unique and proprietary method that AeroFarms uses, based off a technology called "aeroponics."

David Slotnick/Business Insider

Aeroponics is a seemingly simple but cutting-edge growing process.

AeroFarms

It uses a mist of water and air to help crops grow in an environment without soil, pesticides, sunlight, or weeds. Aeroponics farms can grow crops year-round, regardless of season.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

It starts with a cloth-like material on which seeds are placed, and where the roots will eventually take hold. The material is laid across trays, which are placed into the farm's growing racks.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

From there, the farm uses a mist of water, coupled with nutrients, to start the seeds' growth.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

Instead of sunlight, the farm uses LED bulbs emitting specific light spectrums, designed to discourage pests, optimize the nutrients the plants get, and even control the flavor of the plants.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

With this method, AeroFarms can grow mature, ready-to-harvest plants in a fraction of the time of a normal farm.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

While baby leafy greens would normally take 30–45 days to reach maturity, AeroFarms said that it only takes AeroFarms 12–14 days.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

That faster growth means that food can be supplied faster, keeping up with demand while using just a fraction of the energy.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

Within just a few days, the farm will see its seeds begin to germinate...

David Slotnick/Business Insider

...Begin to grow...

David Slotnick/Business Insider

... Take hold in the cloth medium ...

David Slotnick/Business Insider

... And grow ...

David Slotnick/Business Insider

... And grow ...

David Slotnick/Business Insider

... And grow.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

The farm has a variety of high-tech solutions to optimize plant growth, including computer-controlled misting...

David Slotnick/Business Insider

... Temperature controls ...

David Slotnick/Business Insider

... And systems that help manage the growth environment, ranging from fans, controlled air pressure between different rooms, and more.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

The racks of trays resembled a server room in an office, except that each row had plants growing on it ...

David Slotnick/Business Insider

... Something you typically wouldn't see around computer servers.

Singapore Airlines

Sensors, controls, and backups help ensure that the plants can grow in the best conditions possible ...

David Slotnick/Business Insider

... And make it easier to keep track of different crops and growing cycles.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

Employees and visitors take a number of precautions to avoid accidentally interfering with the growth or contaminating the food-bound plants ...

David Slotnick/Business Insider

... Including removing jewelry, entering through a series of pressurized rooms and doorways, and wearing hair nets, gowns, gloves, and more.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

The farm employs about 150 people.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

Once plants reach a certain point...

David Slotnick/Business Insider

... They're ready to go into the food supply — including in Singapore Airlines' dishes.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

Growing trays can be taken individually to the harvest room, whenever they're ready — unfortunately, we weren't able to take photos of the process ...

David Slotnick/Business Insider

... And then to the packaging room ...

David Slotnick/Business Insider

... Where they're packaged either for bulk delivery to clients like Singapore Airlines, or for retail.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

The growing, harvesting, and packaging operation may be unique ...

David Slotnick/Business Insider

... But AeroFarms is planning to expand, hoping to open additional locations.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

Business Insider sampled a few different harvested greens, including baby kale, and spicy watercress.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

After being packaged, the sky-bound greens are trucked to nearby Flying Food Group — the caterer that supplies Singapore's Newark flight, which is about four miles away — where they're used for the day's dishes. The airline said it would start with three appetizers, including a garden green salad, heirloom tomato ceviche, and a soy poached chicken, pictured here.

Singapore Airlines

Then, the dishes are brought from Flying Food Group just down the road to Newark Airport, where they're loaded onto the plane.

Nicolas Economou/NurPhoto via Getty Images

If you're interested in trying AeroFarms' produce and you're located in the New York City metropolitan area, the farm sells packaged goods in local grocery stores under the brand name Dream Greens.

David Slotnick/Business Insider

Thinking Outside The Box: RIT Hydroponic Farm Changes The Dining Experience

The lettuce is tasting fresher at RIT’s main campus since the university installed a hydroponic farm-in-a-box behind the Student Alumni Union

September 23, 2019

A. Sue Weisler

Inside the 40-foot-long farm-in-a-box, farm manager Dave Brault harvests some leafy greens. By using a vertical hydroponic system, Brault is able to maximize the farms growing space.

The lettuce is tasting fresher at RIT’s main campus since the university installed a hydroponic farm-in-a-box behind the Student Alumni Union.

Made from an upcycled freight container, the new RIT Hydroponic Farm will provide fresh produce for the chefs who serve nearly 14,000 meals on campus every day. So far, the farm has produced roughly 40 pounds of greens since farm manager Dave Brault started harvesting in early August. Once Brault establishes a consistent growth cycle, he hopes to harvest roughly four times per month.

A. Sue Weisler

Produce from the farm is already being used in Brick City Café and by RIT Catering. In the future, the produce will be used at all dining areas on the main RIT campus.

Rather than using soil to grow plants and provide them nutrients, plants on a hydroponic farm get everything they need from water. Using a vertical hydroponic system for RIT’s farm, Brault anchors the seedlings in a breathable mesh that allows for water flow, and he hangs them from the ceiling in long containers to maximize space.

RIT is one of few universities in the United States that has implemented a hydroponic garden to help sustain its dining needs. Stony Brook University, the University of Arkansas and Clark University have also had success using the same hydroponic set-up RIT adopted, purchased from Freight Farms.

“It helps us stand apart from other universities. This is how we keep RIT and RIT Dining at the forefront of innovation,” said Denishea Ortiz, director of strategic marketing and retail product management for Auxiliary Services. “It is one of many steps that we have taken to highlight the fact that RIT has an innovative campus beyond the classroom.”

Right now, Brault is focusing on growing smaller, leafy greens like basil, cilantro, kale, arugula and different varieties of lettuce. Going forward, he will get feedback from RIT chefs to see what types of produce are in high demand.

“This is square one and from here we have a huge opportunity to turn this farm into something lasting and impactful,” said Brault. “Hopefully, other universities will see that it can be done and that the logistical challenges in implementing something like this are not insurmountable.”

Gabrielle Plucknette-DeVito

Emma Junga, a third-year mechanical engineering student with a concentration in energy and the environment, works at the farm a few days a week. After taking a tour of the farm, Junga was interested in the process and asked Dave Brault for a job. Now, she helps care for the plants, including planting and harvesting, and helps give tours to help share information about the new farm.

Ortiz explained that the goal is to provide produce for all dining facilities on campus. Before they can roll things out on a larger scale, Brault and RIT Dining are experimenting with the growth cycles and outputs to learn what the farm is capable of.

The greens from the hydroponic farm are currently supplying produce for Brick City Café and are being used by RIT Catering.

“Brick City Café is known for its salad bar, thus the proximity of the farm is a chance to provide a literal farm-to-table experience,” Ortiz said. “The produce is fresher and contains more nutrients.”

Before coming to RIT, Brault built and established his own hydroponic farm in the Finger Lakes region of New York. Brault said he looks forward to the unique opportunities the university can provide with its plentiful resources of man-power, brain-power and technological innovations.

“Farming is not something that most people would think involves a lot of technology, but the industry needs these advances to address the challenges that are coming our way,” he said. “I think RIT will continue to find ways to innovate and use technology to help farmers move forward.”

US: CHICAGO - Indoor Farm of The Future Uses Robots, A.I. And Cameras To Help Grow Produce

For the last three years Jake Counne, the founder and CEO of Backyard Fresh Farms, has been pilot testing vertical farming using the principles of manufacturing

September 27, 2019

By: Ash-har Quraishi

Farm of the future uses robots and A.I. to help grow produce

CHICAGO – According to the USDA, the average head of lettuce travels 1,500 miles from harvest to plate. That transport leaves a heavy carbon footprint as flavors in the produce also begin to degrade. While many have looked to vertical farming as an Eco-friendly alternative, high costs have been a challenge.

But inside a warehouse on Chicago’s south side, one entrepreneur hopes to unlock the secret to the future of farming.

For the last three years Jake Counne, the founder and CEO of Backyard Fresh Farms, has been pilot testing vertical farming using the principles of manufacturing.

“Being able to have the crop come to the farmer instead of the farmer going to the crop,” said Counne. “That translated into huge efficiencies because we can start treating this like a manufacturing process instead of a farming process.”

It’s a high-tech approach – implementing artificial intelligence, cameras, and robotics that help to yield leafy, organic greens of high quality while reducing waste and the time it takes to harvest.

Some have called it Old McDonald meets Henry Ford. Large pallets of vegetables are run down conveyor belts under LED lights.

“The system will be queuing up trays to the harvester based on where the plants are in their life-cycle,” explains Counne.

It’s the automation and assembly line he says that makes this vertical farming model unique. Artificial intelligence algorithms and cameras monitor the growth of the crops.

Lead research and development scientist Jonathan Weekley explains how the cameras work.

“They’re capturing live images, they’re doing live image analysis,” he said. “They’re also collecting energy use data so we can monitor how much energy our lights are using.”

“So, what essentially happens is the plant itself is becoming the sensor that controls its own environment,” Counne added.

Another factor that makes the process different is scaleability. Right now, Backyard Fresh Farms can grow 100 different varieties of vegetables with an eye on expansion.

“There’s really no end to the type of varieties we can grow and specifically in the leafy greens,” said Counne. “I mean flavors that explode in your mouth.”

And it’s becoming big business.

The global vertical farming market valued at $2.2 billion last year is projected to grow to nearly $13 billion by 2026.

Daniel Huebschmann, Corporate Executive Chef at Gibson’s Restaurant Group, says the quality of Backyard’s produce is of extremely high quality.

“We’ve talked about freshness, but the flavors are intense,” he says. “It’s just delivering an unbelievably sweet, tender product.”

Counne says he has nine patents pending for the hardware and software system he and his team have developed in the 2,000 square foot space. But, he says the ultimate goal is to have the product make its way to grocery shelves nationwide.

“The vision is really to build 100 square foot facilities near the major population centers to be able to provide amazing, delicious greens that were grown sustainably,” he said.

If he succeeds where others have failed, his high-tech plan could get him a slice of the $63 billion U.S. produce market. At the same time, he hopes to bring sustainable, fresh vegetables to a table near you.

Indoor Farming, Crop Monitoring, Pathogen testing Showcased

Six of the nine companies have been featured in recent editions of Agri-View. This article features the final three companies – Alesca Life, Farm X, and ProteoSense

Lynn Grooms lgrooms@madison.com

September 23, 2019

A container-farming system developed by China's Alesca Life features monitoring, automation and climate control. It was developed for food processors and food retailers.

Nine startup companies were chosen to participate in the 2019 SVG Ventures-Thrive Accelerator Program. Silicon Valley Global Ventures, known as SVG Ventures, is a venture capital, innovation, and investment firm. The Thrive Accelerator program invests in mentors and connects startups with investors and businesses for partnerships.

Six of the nine companies have been featured in recent editions of Agri-View. This article features the final three companies – Alesca Life, Farm X, and ProteoSense.

Alesca Life of Beijing has developed various indoor-farming systems. Its container-farming system features monitoring, automation, and climate control. It was developed for food processors and food retailers.

The company also has developed a small cabinet farm for on-site food production in restaurants and schools. The compact system is suitable for growing micro-greens and other leafy vegetables.

Small cabinet farms for on-site food production in restaurants and schools are offered by Alesca Life.

Contributed

“Our target is that customers will see a return on their initial investment within four years,” said Stuart Oda, co-founder, and CEO of Alesca Life.

Stuart Oda is the co-founder and CEO of Alesca Life, which has developed various indoor-farming systems.

Contributed

Another of the company’s indoor-farming systems is “Alesca Sprout.” Developed for hydroponic farms its sensor-based system automates irrigation and other farm electrical equipment.

The Alesca Cloud is a smartphone-based supply-chain-management system. It aggregates operational tasks, farm capacity and production data, operational inventory, environmental sensor data, and other data points.

“Indoor farming is one of many ways to produce food in a hyper-efficient and localized way,” Oda said. “Just as there are different modes of transportation for different types of travel needs, indoor farming is a mode of food production optimized for certain geographies and crop types. As indoor vertical farms become more productive and efficient they’ll be able to produce larger volumes and varieties of vegetables.”

Alesca Life’s turnkey food-production systems enable even inexperienced growers to produce vegetables. The company wants to ensure its customers have positive experiences with indoor farming so it provides troubleshooting for the mechanical and electrical aspects of its systems, Oda said.

Farm X of Mountain View, California, provides growers monitoring and analysis to improve crop productivity. Bill Jennings, chief technical officer for Farm X, discussed the company’s tiers of service in June at the Forbes AgTech Summit.

Bill Jennings

A basic service that Farm X offers involves weather monitoring. The company collects data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the California Irrigation Management Information System, IBM’s Weather Underground and other third-party sources. The company combines the data with imagery from satellites and unmanned aerial vehicles to help growers monitor crop health and performance.

The next tier of service involves the use of in-ground sensors placed every 5 acres to monitor crop health as well as irrigation performance. Farm X combines that information with its models to help growers ensure uniform distribution of irrigation water and reduce electrical costs associated with irrigation pumps.

The third tier of service is a yield-management program. Farm X forecasts crop conditions about three to four months in advance of harvest. That enables growers to improve harvest planning such as how many workers will be needed for harvest. Growers also can use the forecasts to inform their supply-chain partners about future sales, Jennings said. The company’s focus to date has been in California’s vegetable-production areas.

ProteoSense of Columbus, Ohio, has developed a portable biosensor that detects foodborne pathogens such as Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes. Mark Byrne, president and CEO of ProteoSense, has several years of experience working in the medical-device industry. But he saw the need for rapid detection of pathogens in food production and processing.

A portable biosensor developed by ProteoSense detects foodborne pathogens.

Contributed

ProteoSense’s biosensor has been in testing at Taylor Farms of Salinas, California, a large producer of fresh-cut vegetables. The biosensor was first tested in a food-packing house where Listeria monocytogenes can live on countertops, floor drains, coolers, and other equipment.

Food producers have traditionally taken swabs of suspect areas to send samples for laboratory testing. Food producers often need to wait for three days to a week before receiving test results. The ProteoSense biosensor can be used on-site to provide immediate results, Byrne said. Using the biosensor a food producer would take swabs mixed with a buffer. The buffer is placed into the biosensor. The device then displays results and transmits them for storage in the “cloud.”

Mark Byrne

There could be several uses for the biosensor. In addition to being used to detect pathogens on vegetables the biosensor could be used to test irrigation water and ponds for E. coli, Byrne said.

“We’re working with the Pork Checkoff to learn if the biosensor could help pork producers,” Byrne said. “We want to talk with more farmers about how they could use pathogen testing.”

Visit alescalife.com or farmx.co or proteosense.com or thriveagrifood.com or www.forbes.com/series/forbes-agtech-summit -- and search for "agtech summit" -- for more information.

Lynn Grooms writes about the diversity of agriculture, including the industry’s newest ideas, research and technologies as a staff reporter for Agri-View based in Wisconsin.

Best Media For Your Hydroponics Setup?

Does it puzzle you to select the right media for hydroponics setup growing vegetables using the hydroponic method? different Hydroponic formats and hence require different kinds of media

Does it puzzle you to select the right media for hydroponics setup growing vegetables using the hydroponic method? different Hydroponic formats and hence require different kinds of media.

Hydroton

Hydroton or clay balls is expanded round clay pellets and is one of the more widely used media in India. It can be used on its own in hydroponics, aeroponics or deep water culture (DWC) or combined with other media esp. in drip systems (Grow bags, Trough system or Dutch Buckets). It allows maximum drainage and aeration. Hydroton can also be re-used if cleaned and sanitized properly with hydrogen peroxide.

Perlite

Perlite is a medium that is commonly found in soilless mixes. It is made from amorphous volcanic glass that has relatively high water content, typically formed by the hydration of obsidian. Be careful using this media by itself, as it will float.

Cocopeat

Coconut Coir is the most popular medium in India. It is Ph neutral and can be used for multiple months without sterilizing again. It works best when combined with another medium such as hydroton. Coir has excellent nutrient and water holding capacity. It should be cleaned and sterilized after around 6-8 months.

Oasis Cube

Oasis Cubes are manufactured from water-absorbent foam, Phenolic foam, also known as Floral Foam. They act as good starting plug for seedlings and plant cuttings, and not so much as a full growing medium. They are very cheap but have to be changed after every crop.

Jiffy Bags

fine cloth netting is filled with high-quality cocopeat and then compressed to form a “tikky” like coin pellet. It grows to approximately 7 times in height as soon the water is added. Cocopeat is held together by cloth netting and ensures optimum air/water exchange. Available in 1.25 Inch size. It is slightly costlier than the oasis cube but offers better seedling. Like oasis cube, it should also be changed after every crop

Conclusion:

Media plays a very important role in Hydroponic, hence selecting the right and Best Media for your Hydroponics setup is very critical for the optimum growth of vegetables.

Harvard Political Review: Green Thumb

Urban farms currently feed more than 800 million urban dwellers every year, but that number will certainly grow as the world’s population keeps increasing and urbanizing. Indeed, the UN estimated that 68 percent of the world’s population will live in cities by 2050, a larger proportion of a much larger number as the Earth’s population continues to grow more broadly

By Kendrick Foster | September 29, 2019

When I think of a farm, I usually imagine an Iowa cornfield stretching for miles on end. A combine harvester spews out straw in collecting this crop; perhaps it’s destined for our plates, but more likely it will become biofuel. Indeed, forty percent of the nation’s corn supply goes to ethanol. The vast majority of the remainder, meanwhile, goes to feed livestock or to manufacture high fructose corn syrup. Only a small portion of the corn grown on these rural farms is served as corn on the cob at America’s restaurants, barbecues, and supermarkets.

Urban farms differ in every way from the corporate behemoth that Midwestern corn agriculture has become. They are small, locally owned, and grow a wide range of crops, from garlic to tomatillos, callaloo to coriander. In turn, those crops often go directly onto plates, bypassing the dizzying amount of processing that most of our food goes through.

I must admit that I had a different conception of urban farming when I started this project. I imagined a monolithic venture, an industrial enterprise merely ported to the confines of the city. Of course, I was wrong: Even within Boston, urban farms range from small community farms to rooftop gardens on top of Fenway Park to hydroponic operations growing underneath the LED lights of a shipping container.

Urban farms currently feed more than 800 million urban dwellers every year, but that number will certainly grow as the world’s population keeps increasing and urbanizing. Indeed, the UN estimated that 68 percent of the world’s population will live in cities by 2050, a larger proportion of a much larger number as the Earth’s population continues to grow more broadly. Feeding these urban dwellers will require reimagining our agricultural systems, creating a puzzle for policymakers across the globe.

Urban farms can serve as a piece of the answer to that puzzle; increased urban farming will improve food security, aid in environmental justice, and help beautify neighborhoods, all while increasing community happiness. Urban farms certainly need increased governmental support, but policymakers must remember one key thing: Urban farming is a highly localized endeavor, and each city must consider its own local conditions before making generalized policies.

Garlic in the Ground

Jet engines from planes departing Logan Airport roared overhead as I ambled towards the Eastie Farm, just a short walk from Maverick Square in East Boston. The farm looked out of place, sandwiched between two multi-family rowhouses along Sumner Street, but I felt strangely relaxed at the farm, standing in the springtime breeze, smelling the dirt, and observing just a small slice of these plants’ gradual growth process.

Volunteers worked to clear the space in preparation for more fruitful times. Lanika Sanders, an Americorps volunteer assigned to the site, directed the work party while telling me a little more about the farm. This land used to house an apartment building, but community members started using it as a trash dump once the apartments were torn down. A group of concerned residents petitioned the city to clean it up, and they planted some garlic once they had finished. “When the city said time to take it back, they argued that they still had garlic in the ground, so they had to give it to them for another season,” Sanders explained. Eastie Farm eventually took over the space.

One hour and several subway transfers later, the Fowler-Clark-Epstein Farm looked less out of place in Mattapan, home to more yards than skyscrapers. Sprinklers whirred about watering seedlings, and garlic plants tentatively put their leaves in the air. Still, its history echoes Eastie Farms. Along with Historic Boston and the Trust for Public Land, the Urban Farming Institute renovated a 19th-century barn and farmhouse to serve as its offices and restarted farming on a property that had hosted farm operations as far back as the 1700s. The site lay vacant from 2013 until 2017, when the renovation project started. Currently, the UFI uses the site as a working farm, as well as the site of their well-reputed farmer training program, which has launched graduates into urban farms across the city.

Beantown Farming

Recently, the Boston urban farming scene has started to attract press attention — and a lot of it. An article in The Guardian described the city as “a haven for organic food and urban farming initiatives,” while Inhabitat declared Boston the second-best city in the United States for urban farming — just behind Austin.

Urban farms in Boston generally fall into three main categories: nonprofits like the UFI or Eastie Farm; community gardens in which individual farmer can grow whatever they want on an individual plot of land; or businesses out to make a profit. Some farms operate seasonally in traditional or rooftop gardens, while others operate all-year in greenhouses. Notable farms include Green City Growers’ rooftop farm at Fenway Park and a 2,400 square foot rooftop garden at the Boston Medical Center; smaller clusters of nonprofits, community farms, and greenhouses dot the Mattapan and Dudley Square areas. The city also hosts more than 200 community gardens and 100 school gardens.

An art installation outside the Dudley Greenhouse reads “Our Liberated Land” in English, Spanish and Cape Verdean Creole.

Boston has also spawned several agrotech startups that work in the urban farming business. Freight Farms has developed a turnkey farm entirely within a shipping container, ready to grow food as soon as it arrives at its destination. Their Greenery machine uses highly efficient LED panels, a hydroponic nursery, and artificial intelligence to create an extremely efficient automated farm system. Meanwhile, Grove Labs developed a bookshelf-sized hydroponic nursery that homeowners and business owners can control with an app.

Two major components have contributed to the general success of urban farms in Boston. On the technological side of things, a strong entrepreneurial culture means that Bostonians are willing to take risks, and the number of colleges and universities in the area gives entrepreneurs a large pool of talent to draw on to make their ideas come to fruition.

On the farming side, the 2013 passage of Article 89 changed the city’s zoning regulations to permit farming and beekeeping within the city’s jurisdiction. UFI played a major role in working out the kinks in this legislation, Patricia Spence, its Executive Director, described the process when I visited the Fowler-Clark-Epstein Farm. “We were the guinea pigs, in essence … We’ve got the water people, the inspection people, all these different entities that now have to work together in concert.” Even though some of the kinks still create problems, Boston farmers do not have to worry about the legality of their farms or greenhouses, unlike urban farmers in other cities who have to acquire permits on a case-by-case basis.

Out of the (Food) Desert?

The people I spoke with had differing motivations for entering the urban farming field. Spence remembered the importance of family in getting her start in urban farming. As we walked around the Fowler-Clark-Epstein farm in Mattapan, she recounted her story. “My grandfather farmed every piece of the property he owned in Roxbury, and we certainly ate from the yard. My mom and dad bought a vacant lot in Dorchester, and my dad grew food there all summer long. The passion comes from that vantage point.”

Karen Washington, meanwhile, remembers being galvanized by then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s proposal to auction off community garden sites. “Growing in empty lots wasn’t really about food. It was about beautification, taking back our neighborhood,” Washington, a food justice activist and founder of the suburban Rise and Root Farm outside of New York City, told the HPR. “In the middle of the night, we got backstabbed when Giuliani tried to auction off 100 community gardens. Looking back, it was the best thing that happened, but during that time, it was the worst thing that happened. People were telling us we couldn’t fight city hall, but then we said collectively we could fight city hall. A group of community gardens along with your allies, you’re much stronger. You can’t work in a silo, but when you get a community behind you, you can be a lot more successful.”

However, many people at the helm of Boston urban farms got their start in urban farming after they recognized the deficiencies in both local and national food systems. Jessie Banhazl, founder of Green City Growers, read the book Omnivore’s Dilemma, which inspired her to grow food more organically and sustainably. After moving back from New York City, she also realized something about the broader food system. “Upon returning back to the Boston area, I realized that I had been living in a food desert and that I was really feeling the effects of not having access to fresh produce,” she told me. Apolo Cátala, farm manager of the OASIS at Ballou farm in the Codman Square area, realized something similar after going on sabbatical in Puerto Rico.

Many the problems in these food systems center around nutrition and public health. “Many times, people have to go outside of their own neighborhood to find something that’s fresh, that’s edible, instead of the the junk food that’s inundating our community,” Washington said. When people eat junk food instead of fresh fruits and vegetables, their health declines — researchers have linked food deserts, areas without affordable access to fresh fruits and vegetables, to increased rates of obesity and diabetes. Obesity and diabetes disproportionately impact low-income Americans and people of color precisely because low-income Americans and people of color disproportionately live in food deserts.

Boston’s food system in particular presents numerous challenges for low-income residents. Overall, Boston has 30 percent fewer grocery stores per capita than the nationwide average, and predominantly minority neighborhoods in Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan have even fewer, Barbara Knecht, the farmsite development coordinator at UFI, told the HPR. A Boston Globe investigation, meanwhile, found that 40 percent of Massachusetts residents live in a food desert. Even Harvard Square, home to affluent Harvard students, is widely considered to be a food desert.

Broader questions, though, revolve around the sustainability of our food supply and its relation to population growth. America’s farmers are notoriously inefficient. They consume large amounts of water, drawing on aquifers much faster than they can be replenished, and spray an inordinate amount of pesticides and fertilizers, creating a host of environmental issues, from resistant pests to algal deal zones. Meanwhile, the problem of overpopulation is always looming. Jon Friedman, the co-founder and COO of Freight Farms, told the HPR. “Our population is set to exceed our capabilities for food production, and that’s a big, hairy program that we have to solve,” he said.

Meanwhile, Dickson Despommier, a professor at the Columbia School of Public Health, connected urban farming and climate change in conversation with the HPR. “Climate change issues require a different approach because farmers can’t move when the climate changes. They grow corn where they live now, but in twenty or thirty years they won’t be able to because the climate won’t permit it,” he noted.

By bringing fresh produce into cities, urban farming can help address the racial inequalities that characterize food access in America.

It’s easy to imagine these problems converging in coming decades. Climate change causes refugees from low-lying areas to flock to cities, where they go hungry because rising seas have destroyed much of the world’s arable farmland. If they can eat at all, they rely on junk food because the remaining fecund land grows high-profit or subsidized crops. In its own way, urban farming can make a contribution to stop this spiral. It makes use of previously unutilized areas — especially rooftops and vacant lots — to grow more fresh, nutritious food, selling it to the communities that need it most at affordable prices.

Although urban farms do not necessarily operate under organic principles — a set of rules including prohibitions on pesticides and artificial fertilizers — many in the Boston area, including UFI and the OASIS farm, do. Those that do not are typically small, meaning that they cannot indiscriminately spray pesticides or fertilizer. The high price of water in many cities, meanwhile, has forced urban farmers to control their water usage or find new ways to get water.

Innovations in farming practices allow urban farmers to grow their produce without pesticides and fertilizers. In setting up a controlled environment for plants in a shipping container, Freight Farms has created a technology that allows plants to grow more efficiently, with inputs exactly tailored to the plants’ needs. “We’ve uncovered a world of ways that we can help the plant do what it wants to do best or do something it’s never been able to do without the use of chemicals, fertilizers, pesticides, and the like,” Friedman explained.

Beyond its environmental benefits, the green space created by urban farms also lifts property values and community spirits. Urban farming “turns urban spaces back into places where plants are being grown, where there’s oxygen being created, where there’s beautification happening,” Washington explained. “When you go from a vacant lot to an urban farm, it makes people happier.”

Banhazl added that urban farming helps to reduce emissions by decreasing the distance between the source and the consumer — a concept known as reducing ‘food miles’. “By localizing food, you cut down on all sorts of carbon emissions and use of resources [associated with] moving and trucking and distributing food from one point to another.”

Both Banhazl and Friedman emphasized the nutritional benefits of their business models. “The sooner you pick the food and then put it in your mouth, [the more] nutritional value you will get out of that plant,” Friedman explained, and the hyperlocal nature of Freight Farms’ containers (often located right next to the main consumers of the produce, such as restaurants as grocery stores) puts healthy produce into communities that need it. Furthermore, when local residents replace junk food or processed food with fresh vegetables, their health improves. “The whole idea is we’re tapping into local knowledge about healthy food and expanding it,” Knecht of the UFI explained.

Boston high school students visit the Freight Farms shipping containers, learning about innovations in agrotech.

Farming for Fairness

Every single person I spoke to emphasized food security in relation to urban farming. Many of the community gardens and nonprofits across Boston sell their produce at farm stands and farmers’ markets in their local communities, improving food access. Green City Growers donates a portion of their produce to local food banks and soup kitchens, while school gardens help provide at-risk teenagers with fresh produce in school lunches. Volunteering programs at many urban farms also provide residents with the opportunity to work with nature, which in turn encourages them to pick healthier foods when they go to the supermarket. In addition to teaching local residents how to grow their own food, the UFI’s farmer training program also helps them to develop useful skills for the workplace.

Above all, urban farms help to inspire the local community to grow their own food, which does the most to improve food access and nutrition. “The most successful thing is to inspire people to make a stronger connection to where their food comes from,” Cátala told me. “We have the ability to engage entire communities. It’s a small scale, but it’s still a scale that has a big impact, and it’s important to measure that.” Patricia Spence reiterated the importance of this point: “We say, whether you’ve got a little bit of dirt in the backyard, if you’ve got a porch, if you’ve got a windowsill, we want you growing food.”

Spence noted the impact urban farming can have beyond nutrition, citing two stories that have stuck with her. “Chris was a part of our class of 2014, and the success of our program is Chris’s story. He was reentering the workforce, he had been incarcerated. It took him a year or two to get into the program, but he went through the program in the 2014 year, lost 100 pounds, and learned what a real tomato tastes like. He became our tomato expert,” Spence began.

“He went on to work with at the Commonwealth Kitchen, this wonderful incubator of food businesses. A lot of the food trucks you see around the city actually do their food there. Chris started with working them, but after two years, he actually was like, ‘I miss the dirt!’ So he came back, and he was with us seasonally for the past two years, and he became our production manager. As of this year, I’m sorry to say, he’s not coming back because he has a full-time job at the Commonwealth Kitchen, and he’s a manager. I am sad, but it’s exactly what we want.”

“If you look at Ronald, it’s a similar story. When Ronald came to us, he was extremely quiet, a very, very quiet man, didn’t say a word. But he was a prolific journaler. He just wrote and wrote. We had to keep giving him journal books. By the end of the class, everyone was saying, ‘You talk all the time now!’ He went to work for the Commonwealth Kitchen as well, and he’s been there for four years. We had a big fundraiser last year, and he was asked to speak. This guy who didn’t speak spoke for seven minutes, I timed him, no script. He said this was the best year of his life.”

Up, Up, and Away

Dickson Despommier thinks he has another way to transform lives through food: vertical farming. Vertical farming is not a new idea, but its widespread implementation in the United States could radically change the way we think about urban farming. The HPR interviewed Despommier, who originally came up with the idea in 1999; he defined vertical farming as a “multiple-story greenhouse.” In the first few years, Despommier and the students who worked with him labored in obscurity. “We just carried out as if we were living on an iceberg somewhere floating in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, and nobody would ever read anything we did or care about what we did, so we did whatever we want. That’s the best way to approach any problem: There’s no limits on the kinds of solutions you can suggest for something as long as the solutions make sense ecologically.”

In recent years, though, larger-scale farms making true use of the vertical farm concept have sprouted up in cities across the world. AeroFarms has four farms in the city of Newark. Using what it calls a “smart aeroponic” technology, it claims to use 95 percent less water than traditional agriculture to produce yields of 370 times that of the standard model. In Japan, Spread Company recently built a vertical farm in ‘Japan’s Silicon Valley’ with automated temperature, humidity, and maintenance controls. Singapore’s Sky Greens also operates a commercially successful vertical farm, consisting of several 4-story translucent structures. Many other businesses have developed smaller-scale vertical farm operations that can take advantage of unused garage space in private residences.

At this point, three major technologies form the basis of the majority of indoor farming projects globally: hydroponics, aeroponics, and aquaponics. Despommier described each system for the HPR. In the main hydroponic technology, plant roots take in an oxygen-infused nutrient mixture through holes in PVC pipes. However, this technology suffers from competing temperature priorities: High temperatures allow more nutrients to be dissolved but also less oxygen. Despite this, the technology remains common: Freight Farms and Grove Labs both rely upon hydroponics for their systems.

Freight Farms uses innovative technologies and methods like hydroponics to grow produce within shipping containers.

Aeroponics solves the temperature problem in hydroponics by suspending roots in a chamber, where a nutrient-rich mist is sprayed. However, aeroponics has a valve problem: The valves involved in spraying the mist “routinely clog up, and that became a big problem with troubleshooting. It’s a mess,” Despommier said. Fortunately, a Chinese company, AEssence Grows, has developed a much more reliable valve, one that makes aeroponic systems a lot more viable, he told the HPR.

A third option has also emerged: aquaponics, a combination of aquaculture — fish farming — and hydroponics. In aquaponics, the farm owner feeds tilapia or other kinds of herbivorous fish plant material. The fish then, for lack of a better expression, excrete waste into the water. After the farmer removes the ammonia from the system, the plants take up the nutrients from the fish waste. “This sets up an internal circular economy among the fish and the plants, and you get both for the price of one,” Despommier explained. “However, the big difficulty of this is that you get two completely different growth systems to worry about at the same time. Lots of things can go wrong, and they usually do.” As a result, aquaponics technology will require a lot more innovation before it can enter the world of large-scale vertical farming.

Any vertical farming project would need to be underpinned by one of these technologies, but Despommier has his favorite. “I think aeroponics is going to take over … You can squeeze in many more plants in aeroponics than hydroponics, and aeroponics uses far less resources, including water.”

Vertical farming makes a certain amount of sense agriculturally: you can grow food up instead of just out, and you can grow year-round indoors. Whether it makes sense economically, however, is another question: A recent study found that controlled environment agriculture (a more general term for indoor growing using technologies like hydroponics) in New York City contributed minimally to food security while expending significant resources on the controlled environment itself.

The answer to the vertical farming question may not be skyscrapers filled with stories and stories of aeroponics, but small hydroponic or aeroponic systems in people’s garages. Vertical farming technology seems more suited to for-profit businesses and restaurants hawking hyperlocal produce rather than community organizations focusing on city-wide food security.

Farms from Sea to Shining Sea

Boston has become a hub for urban farming, but many of the largest American cities have their own thriving urban farming ecosystems which include and go beyond vertical farming. It would be mind-numbingly boring to list the urban farms successfully operating in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and a range of other American cities. Cities with an especially sustainable and progressive bent, such as Austin, Seattle, and Portland, are particularly well-known for their urban farms.

Urban farms in these cities generally follow the same model as Boston: a mixture of nonprofits and businesses, greenhouses, rooftop farms, and more traditional farms. Chicago’s urban farms deserve some special note: The city boasts the world’s largest rooftop farm and the country’s largest aquaponic formation. New York schools, meanwhile, have introduced programs that allow students to grow food for their own cafeterias.

Although urban farms have their place in thriving cities, they can also play a role in revitalizing Rust Belt cities suffering because of the steel industry’s decline. Nonprofits have proposed turning vacant Cleveland lots into urban farms that could serve as the centerpieces of new communities, looking to Detroit — a real-life case study for urban farming, its relationship with food and racial justice, and its role in urban renewal. The housing crisis left lots vacant across the city, and many farmers have come to view these lots as an advantage. For example, a for-profit company recently bought 1,500 vacant lots to develop into the world’s largest urban farm. Community gardens have also bought vacant lots, where African-American and Hmong communities, among others, have used the idea of urban farming to reclaim their cultural heritage, educate their youth about food issues, and regain agency in food production.

Mary Carol Hunter, a professor at the School for Environment and Sustainability at the University of Michigan, agreed to talk to the HPR about the urban farming scene in Detroit, which she noted was, of course, too expansive to cover entirely in a single interview. Initially, Detroit urban farms faced strict regulations on the sale of food, Hunter explained, but then an entrepreneur named Dan Carmody stepped in. Carmody, who took over the local food wholesaler Detroit Eastern Market, “decided it was important to have it be a community building, even though it was a for-profit business,” she said. Over the better part of a decade, the market set up a nonprofit “to help people get a business started where they could sell their food and [gave them] all the support services that went along with it … They really wanted to get a value-added product from the food.” This nonprofit has been instrumental in enabling urban farms in Detroit to create jobs and make money selling local, nutritious food, Hunter argued.

Another key figure in the thriving Detroit urban farming scene is Malik Yakini. A former teacher and principal, Yakini realized the “incredible benefit [that] came to the kids who were actually participating” in hands-on farming. Today, Yakini runs the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network, which has emerged as an important voice in Detroit’s black community on a number of issues besides food security.

A second nonprofit, Keep Growing Detroit, has also served as a key actor in growing the Detroit urban farming industry. Several years ago, the organization realized that “they would be a much more powerful group if they focused on teaching leaders in all the communities and having them bring the information back to their own neighborhood,” Hunter said. That approach, she argued, “almost single-handedly removed the neoliberalism problem of nonprofits going into underserved areas and trying to ‘help.’”

Despite this range of benefits, urban farms have not received an exclusively positive response. The Atlantic’s Conor Friedersdorf argued that vacant lots in San Francisco should be transformed into affordable housing units instead of urban farms, while the Detroit Metro Times criticized what it called “colonialism” in one urban farm giving away its produce. By giving away food for free, the farm competed with other locally-owned farms that sold their produce at farmers’ markets, ultimately harming the community, the paper charged. Environmentally, meanwhile, a recent study from Sydney, Australia found that urban farms there used as much fertilizer as conventional farms.

Some of these concerns have merit, particularly ones regarding affordable housing, but each of these three critiques of urban farming examined one city in particular, and urban farming projects all have different local constraints. What may work in one city may not work in another, and vice versa. Putting community members at the helm of these urban farming projects can mitigate some of these concerns by allowing people with local knowledge to make crucial decisions around priority-setting and program design.

“By Definition Challenging”

Of course, the main challenge urban farmers face is the environment. “If any farmer or gardener says they’re an expert, they’re lying, because the only expert is Mother Nature. She will bring you to your knees if you think you know it all, she’ll test you,” Karen Washington said. For example, the OASIS on Ballou farm struggles to contend with its hillside location, Apolo Cátala told me. Meanwhile, Phoenix urban farmers must heavily irrigate their farms or use native plants since their city is located in the middle of a desert. Unsurprisingly, Phoenix’s heavily alkaline, salty, and rocky soil is quite poor.

Detroit urban farmers, meanwhile, contend with industrial pollutants such as lead and mercury in the soil leftover from the city’s industrial heyday. Leaded gasoline and “manufacturing concerns were the worst pollutants, and the stuff is airborne. But [lead] is everywhere,” Hunter said. “I know that in the area of the Ambassador Bridge, there have been some [manufacturing] plants … that still release a lot of airborne toxins. People who live in those areas are reminded and encouraged not to grow leafy vegetables like lettuce because those plants actually absorb [the pollutants] directly from the air right into the food that you eat.”

Interestingly enough, artificially high water prices in Detroit also contribute to the city’s urban farming challenges. “Despite the fact that Detroit has a huge amount of quite delicious and healthy water, it costs a lot more than water should cost,” Hunter noted. Additionally, the city of Detroit has charged high fees to maintain its aging and crumbling infrastructure. “So people have had to do as much as they possibly can to set up gardens that are water-wise and set up things like rain barrels. It’s an economic issue, not a conservation issue.”

The question of money came up time and time again. “Ask Harvard for a million dollars, some of that endowment money would be much appreciated,” joked Patricia Spence of the UFI. “We could be growing more food on more lots, but the financing has slowed up the process considerably,” she continued more seriously. Washington also turned to the question of resources. “In marginalized communities, resources are next to none. Nonexistent,” she said, skewering local politicians for not providing enough money to urban farming.

Banhazl also emphasized the difficulty associated with getting funding in the beginning stages of her business. “We didn’t have the opportunity to raise a ton of capital all at once because people were like, ‘Why would I invest in local farming? That doesn’t seem like a viable commercial business,’ which clearly it is,” she noted. The process of getting money in fits and spurts, she explained, took up a lot of her time in the formative years of Green City Growers, reducing her ability to focus on innovating and developing.

Indeed, despite the local nuance associated with urban farming, this lack of money seems to be a consistent problem across the country — even in cities with favorable regulatory frameworks. California recently passed tax incentives to convert vacant lots into urban farms, while Houston has no zoning regulations whatsoever. Yet urban farmers in Los Angeles have not taken the state up on its offer, with some landholders reportedly holding off for future development or because urban farms simply do not make enough money. Similarly, land in the Houston urban center is surprisingly expensive, and one of the few urban farms in the city worries that the city will terminate its lease in favor of future development.

Creating the Green Thumb