Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Urban Farming: The Challenge of Producing Food in a City | Urban Roots Farm

Urban Farming: The Challenge of Producing Food in a City | Urban Roots Farm

by Pablo Fuentes | Last Updated July 5, 2017

There are a ton of benefits to urban farming.

Local food, farm to table, 100 mile diet, all of this is possible with urban agriculture. Further, urban gardens are often built over abandoned spaces in cities, converting them into green space, helping increase the beauty and value of the neighborhood.

However, there are also many challenges with urban farming. There's potential contaminants from city water runoff, zoning laws that must be overcome, laws about owning chickens, bees, and other farm animals, as well as major space constraints.

We get into all this and more on the latest episode of Small Business War Stories featuring Mel Millsap of Urban Roots Farm.

Listen to the podcast:

We Are Building A Farm Out of Shipping Containers in Downtown Mobile

We Are Building A Farm Out of Shipping Containers in Downtown Mobile

JULY 2, 2017

“We are building Shipshape Urban Farms, eight hydroponic farms, on St. Michael Street in downtown Mobile. The whole space is the equivalent of a 20-acre farm on less than 1/4 of an acre and over 56,000 plants can grow at once. We will harvest nearly 9,000 heads of lettuces, herbs, leafy greens, and small vegetables a week and the growing season is 365 days a year. The farm is built from repurposed shipping containers because shipping containers were developed in Mobile in the 1950’s. The first harvest will be the end of November or the first of December. We can also host garden parties and events there.

Baldwin County was all farmland when I was a kid and now it is track houses. We are creating a way to take farmland back in a very small space by growing vertically instead of horizontal and using three-dimensional space. We have also taken out environmental pressures by using LED lighting and drip irrigation systems so plants don’t have to grow in soil. Everything is dense and the root structure sits in a permeable mesh. The water recycles through, it gets to the bottom and goes back up again, so we use the equivalent of 10 gallons of water a day. That is 90 percent less water than a traditional farm. We will be non-GMO and won’t use any pesticides

We will also grow herbs on a vertical wall that is about 700 square feet. We are doing an annual CSA, which is Community Supported Agriculture, and people can buy a share of a crop. It is a way to keep food local and support farmers.

Angela and I have been working on this for nearly two years. I have a background in landscape architecture and urban planning and she has a background in horticulture and she researched hydroponics. I worked for the Bloomberg team and went to work for Auburn as an adjunct professor then we started Shipshape. I am an Iraq war vet and this will have a certification for Homegrown Heroes, certifying this farm is produced by a veteran family. Starting a business is stressful and financing is challenging. It took a while to get our first dollar and show the banks that Mobile wants this. People can support it now by signing up for the CSA.

“This farm has been the focal point of all of our conversations the last two years. We had to figure out how to do bring this to Mobile. We are lucky that our backgrounds compliment each other.”

“We plan to sell to restaurants downtown, farmers markets, and directly to the consumer through CSAs. A lot of the local restaurant owners are interested. Nothing that is worth doing comes easy. Several years ago, people thought we were crazy to live downtown, now everyone thinks it is amazing and asks how they can get an apartment. It is cool to be in Mobile at this time. We are 20 years too late to hit the big cities like Seattle and Austin but you can make a” big difference here. Downtown Mobile two years from now is going to be a very different place from where it is today. It is totally different than it was two years ago.”

“We talked about going to a big city where it would be easy to start this farm, but we wanted to stay here and bring it home. We would like to expand it to other areas on the Gulf Coast.I look forward to seeing our name on a chalkboard outside of a restaurant. It gives me chills thinking about it.”

“Science brought us together. We met in a Biology lab at Faulkner. I walked into class late and she was sitting in the front row. I sat next to her because I thought she was cute.”

“We started as study buddies. I am sure we made the people behind us want to throw up. We were taking night classes and the labs were long. We had the highest grades in the class because studying was an excuse to be together. I guess it worked.”

(You can support Shipshape Urban Farms by joining their CSA)

Urban Settings Proving To Be Fruitful For Farming

Canadian Demand Exceeds Supply

Urban Settings Proving To Be Fruitful For Farming

When you consider the amount of land given to properties in cities, most would think it only enough for a patio, some furniture and maybe a pool if space (and finances) permit. On the other hand, there are a handful of individuals starting their own urban farms right in their back yards.

3,000 sq ft. of Property

They’re spread few and far between across the province of Ontario; there are maybe three in the city of Hamilton. One such farm, open officially for business as of this past February, is FieldMouse Farms. Owner, Rebecca Zeleney is working with just over 3,000 square feet of property and the biggest piece of equipment she uses is a walk-behind tractor. “Right now we’re in the process of opening one quarter acre of new land,” she said. Not included in the total square footage are the microgreens, which are grown indoors in a nursery attached to the house. Their biggest producer is salad greens (including beet greens, red Russian kale, arugula and spinach). That’s the priority of what I’m growing,” she said. Second to that would be her baby root vegetables (carrots, radishes, salad turnips, beets.)

Massive Demand

Zeleney’s produce is sold locally to restaurants and independent grocery stores. “I also try to price my product so it’s accessible,” she explains, although once produce gets to the grocery stores she has no control over their markup. “Demand in Hamilton is massive for these kinds of products,” she said, adding that she’s nowhere close to meeting it. However with the 120 units of product per week that she moves she feels the farm is doing very well for the land they have. “Off 250 square feet I can harvest about 10 lbs. a week.” While the farm isn’t certified organic, and being in an urban setting it would likely never be, they do grow to organic standards, using non-GMO seeds. “We sell absolutely everything we grow every week,” she said. There aren’t any plans for a brick and mortar storefront or online orders; she doesn’t think selling online would make sense – and maybe that’s just too far down the road.

Surprisingly – and thankfully for the future of the industry - Zeleney says she always wanted to farm but for a long time she thought the barriers were insurmountable. “A lot of people think land ownership is a barrier to farming, or not having the knowledge. I’m lucky in the sense that I grew up around farming.” She had also done many apprenticeships related to farming in the past. “There’s always more to know,” she admits. “I never felt knowledge was my barrier – just land.”

The home they purchased in Hamilton had a backyard, so they decided to go for it. “I didn’t want to sit around and wait until we had money to purchase a parcel of land.” Urban farming has a somewhat altruistic notion about providing food to a certain demographic, according to Zeleney, or being able to provide food within a tighter radius. “I think the majority of people are getting into it because they like to farm but don’t have access to large land. People are having to make due with what they have and actually realizing that it works.”

For More Information:

Rebecca Zeleney

FieldMouse Farms

These Kale Farming Robots In Pittsburgh Don't Need Soil Or Even Much Water

These Kale Farming Robots In Pittsburgh Don't Need Soil Or Even Much Water

AARON AUPPERLEE | Monday, July 3, 2017, 12:09 a.m.

Brac Webb, CIO, Danny Seim, COO, Austin Webb, CEO, Austin Lawrence CTO, of RoBotany, an indoor, robotic, vertical farming company started at CMU sells their products at Whole Foods in Upper Saint Clair,

Friday, June 30, 2017.ANDREW RUSSELL | TRIBUNE-REVIEW

Robots could grow your next salad inside an old steel mill on Pittsburgh's South Side.

And the four co-founders of the robotic, indoor, vertical farming startup RoBotany could next tackle growing the potatoes for the french fries to top it.

“We're techies, but we have green thumbs,” said Austin Webb, one of the startup's co-founders.

It's hard to imagine a farm inside the former Republic Steel and later Follansbee Steel Corp. building on Bingham Street. During World War II, the plant produced steel for artillery guns and other military needs. The blueprints were still locked in a safe in a closet in the building when RoBotany moved in.

Graffiti from raves and DJ parties once held in the space still decorate the walls. There's so much space, the RoBotany team can park their cars indoors.

But in this space, Webb and the rest of the RoBotany team — his brother Brac Webb; Austin Lawrence, who grew up on a blueberry farm in Southwest Michigan; and Daniel Seim, who has pictures of his family's farm stand in Minnesota, taped to the wall above his computer — see a 20,000-square-foot farm with robots scaling racks up to 25 feet high. This farm could produce 2,000 pounds of food a day and could be replicated in warehouses across the country, putting fresh produce closer to the urban populations that need it and do it while reducing the environmental strain traditional farming puts on water and soil resources.

“It's the first step in solving a lot of these issues that are already past the breaking point,” Austin Webb said.

RoBotany is a robotics, software and analytics company aiming to bundle its expertise to make indoor, vertical farming more efficient and economical.

Webb left a job as an investment banker in Washington to attend Carnegie Mellon University's Tepper School of Business in hopes of founding a startup around food security issues. While in D.C., Webb volunteered at the Capital Area Food Bank and donated to food security causes.

At Tepper, he met Daniel Seim, an electrical and computer engineer pursuing his MBA. Seim connected with Webb on his mission. The pair teamed up with Lawrence, who left a prestigious Ph.D. program at Cornell to found RoBotany, and brought in Webb's brother, a self-described nerd who taught himself to code at age 12 and turned into a software and high tech engineering whiz.

The team speaks the same language when it comes to why they formed RoBotany. The population is growing. Traditional farming degrades soil and pollutes water. Current vertical farming takes a lot work and doesn't use labor and space efficiently.

Austin Webb said RoBotany seeks to solve all of those problems. His brother, Brac, said it must.

“This is probably one of the first problems humanity needs to solve,” Brac Webb said.

The company started in June 2016 with its first farm in a conference room at Carnegie Mellon University's Project Olympus startup accelerator in Oakland.

The first version of the farm was 50 square feet and produced about a pound of micro leafy greens or herbs a day. Once the farm was up and running, RoBotany supplied arugula and cilantro to the Whole Foods in the South Hills under the brand Pure Sky Farms. The team delivered its latest produce Friday.

“The company aligns well with our mission of providing high quality, locally grown produce and we are excited about the success of their vertical growing method for urban environments,” said Rachel Dean Wilson, a spokeswoman for Whole Foods.

In February, the company expanded, big time. The team leased 40,000 square feet of warehouse and office space from the M. Berger Land Co. on Bingham Street. Version two of the farm is taking shape in one corner of the warehouse. It will be 2,000 square feet and produce 40 pounds of food per day. Version three is in the works. The team hopes it will be 20,000 square feet and produce 2,000 pounds of food today.

“It does speak to a different form of agriculture,” Lawrence said.

In a RoBotany farm, robots move up and down high racks moving long, skinny trays of plants into different growing environments. The amount and color of LED lights can be controlled. So can the amount and make-up of the nutrient-rich mist sprayed directly onto the roots of the plants.

The plants — micro versions of leafy greens like kale, spinach and arugula and herbs like cilantro and basil — grow in a synthetic mesh rather than soil. The roots hang freely from the bottom of the trays.

Plants grow two to three times faster than outdoors, Austin Webb said. They use 95 percent less water. And they have the nutritional value and taste to rival any traditionally grown produce, he said.

The company has raised $750,000 to date and hopes to raise $10 million when it closes its first round of financing this summer to begin construction of the big farm. The team hopes to have it up and running by the winter.

Austin Webb anticipates hiring seven to 10 people to work the farm when the full version is running. Another four to 10 people will be needed to run the business end of the company and maintain the robots and software. The robots will do the dangerous work, moving around trays high in the air.

Eventually, RoBotany will expand its crops to include other fruits and vegetables.

“You can't just feed the world on lettuce,” Austin Webb said.

Aaron Aupperlee is a Tribune-Review staff writer. Reach him at aaupperlee@tribweb.com, 412-336-8448 or via Twitter @tinynotebook.

Farm On Wheels Will Deliver Fresh Produce to Indy Food Deserts

Farm On Wheels Will Deliver Fresh Produce to Indy Food Deserts

Maureen C. Gilmer , maureen.gilmer@indystar.com

Published 7:00 a.m. ET June 30, 2017 | Updated 7:09 a.m. ET June 30, 2017

Brandywine Creek Farms Rolling Harvest truck made its debut at the to serve Indy food deserts Circle Up Indy event at IPS School 51 in Indianapolis on Saturday, June 24, 2017. Michelle Pemberton/IndyStar

'I want to see more farmers come together to end hunger'

Jonathan Lawler planted a seed a year ago that has multiplied into so much goodness even he is surprised.

The Greenfield farmer decided last spring to turn a chunk of his livelihood into a nonprofit with the goal to feed the community. Brandywine Creek Farmswas a leap of faith, but its yield is poised to touch all corners of Central Indiana.

"My job as a farmer is to feed the world, and we have people going hungry in my backyard," Lawler said at that time.

Now, he has partnered with two local hospitals to take his farm on the road.

The Rolling Harvest Food Truck, sponsored by Community Health Network, will take fresh, locally produced food into communities where it is scarce, particularly on the city's east side. It will be offered at little to no cost to those it aims to serve.

"Jonathan came to us with his mission of improving access to food for those in food deserts," said Priscilla Keith, the hospital's executive director for community benefit. "But in addition to providing food, he also wants to educate the community, particularly children, about how food is grown, what kinds of food grow here and to let them know fresh food is best if you can get it."

The 30-foot trailer packed with 6,000 to 7,000 pounds of fresh produce harvested at Lawler's Greenfield farm and at an urban farm on the east side will make weekly (or more frequent) stops at four east-side locations: Community Hospital East, 1500 N. Ritter Ave.; Community Alliance of the Far East Side Farmers Market (CAFÉ), 8902 E. 38th St.; The Cupboard Pantry, 7101 Pendleton Pike; and Shepherd Community Center, 4107 E. Washington St.

Eventually, the program could be expanded to the hospital's north and south sites.

Community pitched in $25,000 for some of the pilot program's expenses, while Lawler has invested his time, his expertise and, above all, his heart.

"I've come to the conclusion that hunger is a business for some organizations, and as an American farmer, I want it to be a thing of the past in this country," said the 40-year-old father of three. "I want to see more farmers come together to end hunger because we are the ones who can do it."

Elijah Lawler from the Rolling Harvest truck and Brandywine Creek Farms gives out free tomato and pepper plants during the trucks debut during the Circle Up Indy event at IPS School 51 in Indianapolis on Saturday, June 24, 2017. The Rolling Harvest truck will make weekly stops at east side locations that are being hard-hit by Marsh closings. Michelle Pemberton/IndyStar

Lawler is working with Hancock Health on a similar program dubbed Healthy Harvest, which will travel into Hancock, Madison, Henry and Shelby counties. Hospital CEO Steve Long said the initiative is part of the Healthy 365 movement in Hancock County.

Both harvest trucks will help chip away at food access problems and point people back to the country's agrarian roots through education, Lawler said.

Inside the temperature-controlled Rolling Harvest trailer are vertical growing towers, so visitors can learn how food grows without going to the farm. An educational staffer will be on site at each stop to talk about the benefits of fresh food.

"Food is actually growing in the dirt; it's as fresh as fresh can be," he said. "The towers will be unloaded at every market, and people will be able to see their food growing and harvest it right there."

Keith said the partnership will help address some of the social determinants that affect the health of the hospital's patients and the larger community, and it advances Community's goal of treating patients more holistically.

"We are really encouraged that we have had not just one, but two health partners who now share the philosophy that real food is the best medicine," Lawler said.

Walkscore.com ranked Indianapolis last among major U.S. cities for access to healthy foods in a 2014 study. Only 5 percent of residents live within a five-minute walk of a grocery store. The lack of access to healthy food on the east side has recently become more acute with the closings of the Marsh grocery stores at 21st Street and Post Road and at Irvington Plaza.

This summer, Lawler also is working with Flanner House community center on the northwest side to establish a working urban farm to feed the neighborhood. Flanner Farms sprouted from a dream of center director Brandon Cosby and food justice coordinator Mat Davis to ease the food insecurity that threatened to rob the neighborhood residents of their independence.

"After looking at the food desert issue, we decided to encompass education more into our mission, along with distribution," Lawler said. "Almost everything our society is doing to address hunger is acting as a Band-Aid. I believe that education and local agriculture can be a solution."

More About Urban Agriculture:

This urban farm will feed an Indy food desert

How Hamilton County gardeners are helping feed their hungry neighbors

Call IndyStar reporter Maureen Gilmer at (317) 444-6879. Follow her on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Amazon's Expansive Biodomes Get Their First of 40,000 Plants

When Amazon began building its new campus five years ago, it insisted on incorporating nature in the design.

Amazon's Expansive Biodomes Get Their First of 40,000 Plants

1/8Amazon is building three spheres in downtown Seattle.NBBJ

RON GAGLIARDO JUST might have the most unusual job at Amazon. He spends most of his time tending to the thousands of plants destined for the Spheres, the 90-foot bulbous glass dome in the middle of Amazon’s sprawling campus in downtown Seattle.

Last week, Gagliardo watched as workers pulled an Australian tree fern off of an Amazon Prime truck, carried it through a particularly wide door in one of the spheres, and plopped it into the soil. Australian tree ferns are hardy, primordial plants that can reach 50 feet tall and "a favorite among greenhouse staff," says Gagliardo. This particular specimen spent three years growing in Amazon's conservatory at the edge of town. It is the first of the 40,0001or so plants destined for the domes, which open next year.

Maybe it’s all the screen time or mounting evidence that employees excel when surrounded by nature, but tech companies suddenly love plants. Airbnb installed a living wall in the lobby of its San Francisco headquarters. Apple wants a small forest of 8,000 trees at its new campus in Cupertino. Adobe incorporated biophilic design into its offices in San Jose, California. Yet they all pale compared to Amazon and its three conjoined spheres, which are both meeting rooms and conservatories that will house more than 400 species of rare (and non-rare) plants.

When Amazon began building its new campus five years ago, it insisted on incorporating nature in the design. Employees can open windows in Doppler, the 38-story tower downtown. Plazas teeming with trees dot a campus of 30 buildings. Dogs romp in a park designed just for them. And then there are those spheres, designed to bring the outdoors indoors within the confines of an office building. “The question was, how do we do this in a significant way,” says Dale Alberda, a principal architect at NBBJ, the firm behind Amazon’s new campus. “Just bringing plants into the office wasn’t going to cut it.”

The designers explored hundreds of shapes before choosing spheres. “It’s the most efficient way of enclosing volume,” Alberda says. The domes, made of glass panels on a steel frame, create enclosed biospheres that combine work and nature. That created a challenge, though, because plants and humans like different things. Plants thrive in warm, muggy environments. Humans do not. Amazon may love nature, but it still needs productive employees, so it compromised: The domes remain a pleasant 72 degrees with 60 percent humidity during the day, while at night they're a more plant-friendly 55 degrees with 85 percent humidity.

“It’s people first,” says Gagliardo. “Then we figured out what plants we could put around people.” Gagliardo started with plants found in similar climates. Mid-elevation regions like the cloud forests of Ecuador, Costa Rica, and parts of China fit the bill. A crew will carefully crane a 60-foot tree from California into the domes next month. Once gardeners and horticulturalists plant everything, the dome and its 60-foot living wall will house vegetation from more than 50 countries.

Some of those plants, like moss, ferns and calatheas, have no problem with low light. Others, like the African aloe tree, require full sun. The architects shunned the triangular panels you may know from Buckminster Fuller's famed geodesic dome in favor of the five-sided panels of a pentagonal hexecontahedron. That resulted in larger panels, which allows more sunlight into the sphere. Ninety LED fixtures with light sensors provide additional lighting when necessary.

All those plants need a lot of water, a task Gagliardo prefers to do by hand. “The collection is so diverse that putting everything on automatic sprinklers would be really difficult,” he says. Each day his team of horticulturists will wander the domes amid executives taking walking meeting and office drones doing whatever Amazon's office drones do, tending to plants and rooting around in the dirt. "It's a dream job," Gagliardo says. "I never would have thought I'd be here at Amazon doing horticulture."

1UPDATE 11:55 AM ET 05/6/2017: This story has been updated to accurately reflect the number of plants in Amazon's Spheres

A Night of Chamber Music On Brooklyn’s Floating Food Forest Showed What Cities Can Be

A Night of Chamber Music On Brooklyn’s Floating Food Forest Showed What Cities Can Be

Music platform Groupmuse brought chamber music lovers to the Brooklyn waterfront Wednesday night. It was nice.

By Tyler Woods / REPORTER

Warp Trio's Josh Henderson plays violin on Swale | (GIF by Tyler Woods).

There is something about being on top of the water, surrounded by plants and music to remind you that New York is actually a place on land on the Earth and not a mindset or abstraction.

That was the case Wednesday night, as classical music ensemble the Warp Trio played violin and piano on Swale, New York’s floating food forest, currently docked on Pier 6 at Brooklyn Bridge Park. The ensemble played Ernest Bloch, an improvisation on water, and “Estrellita (My Little Star)” by Manuel Ponce, in an event organized by the online performance platform Groupmuse.

The location was Swale, a farm located on a barge in the East River. It’s both an art piece and a urbanist project, spearheaded by the artist Mary Mattingly. Visitors to Swale are able to explore the forest of edible, perennial plants. The idea is to create a hugely collaborative project that brings together different communities working toward the same goal, and to provide a sort of minimum viable product for how to conceive of a greater system of locally grown food in big cities.

Swale won our Brooklyn Innovation Award last year as the best artist/creative group in the borough working in the innovation space.

The Warp Trio plays Swale. (Photo by Tyler Woods)

“We’re interested in hosting and being a platform for communities that gather and care about each other,” Marisa Prefer, Swale’s education manager, explained. “Groupmuse found us and we were happy to host.”

Groupmuse is a fairly new platform for hosting classical music concerts in small venues like living rooms or other small, nontraditional spaces. We covered Groupmuse, cofounded by a 27-year-old chamber music lover living in Bushwick, late last year.

“Once in a while we decide to do one in public places, but in keeping with the same ethos, which is informal and intimate,” Groupmuse’s cofounder Sam Bodkin explained.

Swale’s Marisa Prefer explains clover and nitrogen. (Photo by Tyler Woods)

As the sun set behind the statue of liberty Wednesday night and the air cooled, the 50 or so attendees on the barge nestled into the wood chips on the ground, steadied themselves on the edges of the barge, and leaned up against the apple trees on Swale.

“It’s a great way to meet new people,” explained Dennis Lin, one of those sitting on the wall of the barge. Lin is also a Groupmuse performer. He’s played living room concerts around Brooklyn and the city. “It’s being able to perform in a nontraditional way and knowing you’re introducing people to classical music who aren’t used to classical music.”

At the end of the evening, after the lights had come on in the Manhattan skyline, one of the Groupmuse organizers asked each member of the audience to shake the hand of someone near them and say one word about how they were feeling.

“Nice,” the person next to me, Elyse, said. Then the audience disembarked from the barge, walking up a metal gangplank, and went their separate ways into the Brooklyn night.

Farming Takes Root In The City

Long the domain of rural areas, commercial farming operations are now starting to take root in urban neighborhoods.

Farming Takes Root In The City

By Gerry Tuoti

Wicked Local Newsbank Editor

Posted Jun 23, 2017 at 2:13 PM | Updated Jun 23, 2017 at 3:18 PM

THE ISSUE: The state Department of Agricultural Resources is preparing to award grants to urban farming projects. THE IMPACT: In five years, the DAR has awarded nearly $1.5 million in grants for 51 projects and nearly 20 organizations.

Long the domain of rural areas, commercial farming operations are now starting to take root in urban neighborhoods.

“Demand has been really strong for this,” said Rose Arruda, urban agriculture coordinator for the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources, which has awarded approximately $1.5 million in urban farming grants over the past five years.

Perched up on rooftops, packed into greenhouses or spread across vacant lots, urban farmers grow a variety of crops to sell to customers in their communities.

High above Boston’s Seaport District, John Stoddard and Courtney Hennessey began farming the roof of the Boston Design Center in 2013. Dubbed “Higher Ground Rooftop Farm,” they lined up several Boston restaurants as customers and sold fresh produce out of kiosks on site at the Boston Design Center.

While working to fine tune his business model, Stoddard decided last year to narrow his focus to supplying smaller numbers of restaurants with fresh ingredients. This year, he’s devoting most of his attention to Boston Medical Center, which hired him to run a 2,300-square-foot rooftop farm that provides produce for the hospital’s food services program and food pantry.

“It’s great that the at the city and state level they are being supportive of trying to figure out how to make urban agriculture work and thrive,” Stoddard said.

Since it launched its urban agriculture grant program in 2012, the state has awarded funding to projects in cities across the state, including Somerville, Salem, Boston and Worcester. The Department of Agricultural Resources will begin reviewing applications for the next round of grant funding in July.

“It’s state money and we want to make sure the money we’re expending is supporting economic development in communities,” Arruda said.

Ed Davidian, president of the Massachusetts Farm Bureau Federation, said he supports the state’s investment in urban farming grants, as long as public funds aren’t being sunk into unviable enterprises.

“I think it’s a good thing, but sometimes you wonder whether the input equals the yield,” he said. “I don’t know if it works on an economic scale, but it could be good in little niche markets. I’m sure it works in some applications and not in others.”

While traditional farms often rely on machinery, it’s not practical to use tractors and other equipment on rooftop farms or in urban settings. For city farms, that means more manpower is often needed. A large portion of their operating costs, therefore, are devoted to payroll.

While community gardens have been around for decades in many cities, commercial urban agriculture is a newer trend.

“A community garden plot is really for personal use,” Arruda said. “An urban farm is a real business. It’s intensively farmed to have produce, vegetables and fruit available for sale in that community.”

Some sell to local restaurants. Others sell to customers who sign up for a farm share, or Community Supported Agriculture program. Most offer their crops at farmers’ markets, and many also donate produce to local food pantries.

The “eat local” movement, which has generated new interest in where food comes from, has helped fuel the small, but growing, number of urban farms in the state, Arruda said.

“I feel like the dust has really settled where that farm-to-table excitement has died down and now the folks who are really serious about farming have stuck with it,” she said.

Gussie Green Students Participate in Fresh Future Farm’s First STEAM Based Summer Camp

Gussie Green Students Participate in Fresh Future Farm’s First STEAM Based Summer Camp

Fresh Future Farm and North Charleston Recreation are excited about the first session of urban farm summer camp that started Tuesday, June 27.

Children from the Gussie Greene Community Center will journal, measure, map, cook and sing about eggs, okra and wood fired pizza prepared with ingredients harvested a few feet from where they are sold. The camp was originally planned for ten students, so Germaine Jenkins, FFF co-founder and CEO, recruited extra volunteers and held an online fundraiser to accommodate the Gussie Green’s twenty-five students. An anonymous donor generated excitement that helped the farm achieve its $2800 goal within a week. The camp focuses on STEAM learning (science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics).

“Forty years ago, a trip to a neighborhood community garden changed my outlook on life and vegetables. I was determined that our neighbors would be the first to experience this hands-on camp.” says Jenkins. “We are humbled to join forces with Karen Latsbaugh of Cities + Shovels (Germaine’s first gardening mentor) and musician Chaquis Maliq and inspire children and families to garden and reconnect with fresh produce. Campers take home recipes and ingredients to recreate meals at home with their families. Who knows, the next BJ Dennis or Will Allen might be mixing fresh parsley and garlic to add to okra soup this summer.” Chef BJ Dennis taught the children about okra’s importance to the Lowcountry and helped campers harvest and prep farm fresh squash blossoms for fresh okra soup. Matt McIntosh of EVO pizzeria will donate dough, cheese and sauce and bake personal pizzas campers prepare with farm herbs and veggies tomorrow, Thursday, June 29.

The farm will host two additional summer camps on July 4-6 and July 25-27 from 8-10:30 am. There are still spaces available in each session. They are still seeking sponsors cover camp expenses – campers from the surrounding area pay $1 per day.

About Fresh Future Farm

Located in the Chicora-Cherokee area, a certified ‘food desert’, Fresh Future Farm uses urban agriculture to improve access to high quality foods in at-risk communities and as leverage to establish socially just economic development. The farm store is also among the small number black operated grocery businesses in the state. All proceeds from sales go back into operating expenses and programming. FFF’s sells fruit, vegetables, herbs and fresh eggs grown on the farm along with a mix of procured produce, fresh eggs, dairy, and basic and specialty grocery staples at fair prices where they are needed most. The farm store accepts SNAP (food stamp) benefits for food, seeds, and plants. Along with the store and now summer camp, the farm offered its first organic gardening class this past spring, and is actively seeking to train residents to help run the operation.

Fresh Future Farm is a non-profit social venture Mrs. Germaine Jenkins, a working class North Charleston resident who was recently recognized as one of the Top 50 Southerners by Southern Living Magazine and is a 2015 Charleston Magazine Community Catalyst award recipient. She created FFF with Growing Power Inc., the national nonprofit urban farm and land trust created by Will Allen, as a model. Fresh Future Farm strives to grow food, healthier lifestyles and the economy in the Charleston Heights area of North Charleston through the following products and services:

Commercial Urban Farm and nNeighborhood Farm Store

Educational farm tours and activities for school youth, families and out-of-town visitors ï Cooking demonstrations and organic gardening classes

Workshops on innovative urban farming techniques

New urban farmer and food entrepreneur incubator

Collaborative community development projects with strategic partners

Fresh Future Farm Mission:

To leverage healthy food and grocery products to create socially just economic development.

For more information about Fresh Future Farm, please visit www.freshfuturefarm.org.

Indoor Farming Plus Made in USA LED Grow Lights: Profile 1.7

Indoor Farming Plus Made in USA LED Grow Lights: Profile 1.7

Green Science and Technology

GREENandSAVE Staff | Posted on Wednesday 28th June 2017

This is one of the profiles in an ongoing series covering next generation agriculture. We are seeing an increased trend for indoor farming across the United States and around the world. This is a positive trend given that local farming reduces adverse CO2 emissions from moving food long distances. If you would like us to review and profile your company, just let us know! Contact Us.

Company Profile: City Bitty Farm

Here is a great example of an urban farm specializing in microgreens and tomatoes.

Here is some of the “About Us” content: City Bitty Farm is a 2-acre diversified urban farm in Kansas City, Missouri. We specialize in growing high-quality microgreens for grocers, restaurants, and special events in our custom-built Four Season Tools high tunnels. We also produce cherry and heirloom tomatoes along with a variety of other vegetables in our outdoor growing plots, as well as transplants for sale. We grow to order, using natural methods to produce the freshest, healthiest, and best tasting food possible.

Designed and built by Greg, greenhouses provide us with space to grow our microgreens, as well as our transplants in the spring. It has many innovative features, including a rainwater capture system, rolling benches, and a bench top hot-water heating system.

Here is the link to learn more: City Bitty Farm

To date, the cost of man made lighting has been a barrier for indoor agriculture. A new generation of LED lighting provides cost effective opportunities for farmers to deliver local produce. Warehouses and greenhouses are both viable structures for next generation agriculture. Here is one example of next generation made in USA LED grow light technology to help farmers: Commercial LED Grow Lights.

Assembly Member Wants To Turn Fallow Land Into An Urban Farm

Assembly Member Wants To Turn Fallow Land Into An Urban Farm

The 15-acre property in question is the former site of the Alaska Native Hospital

By Zachariah Hughes, Alaska Public Media -

June 21, 2017

Officials in Anchorage are taking the first steps to convert a blighted downtown property into an urban farm.

The move comes as an amendment to a five-year management plan for the Heritage Land Bank that’s set to go before the Assembly next week at its June 27th meeting. The 15-acre property in question is the former site of the Alaska Native Hospital, located between Ingra Street and 3rd Avenue. Under the proposal from downtown Assembly member Christopher Constant, the area would first be tested for contamination, then potentially turned into an “urban agriculture center.”

“This doesn’t actually do anything specific toward approval,” Constant said after members of the Assembly’s homelessness committee agreed to move the proposal forward. “It just sends a message to the administration that this is a desirable area to explore.”

Constant represents the area where the potential center site would be.

“The land’s been sitting fallow,” Constant said. “At this point my personal hope is that we’ll do something positive with that land. Let’s put in a farm. And I’m not talking about a garden, I mean a farm.”

Constant would like to see the area grow produce like herbs or greens that can easily be brought to markets and restaurants in Anchorage. One of the eventual goals of the farm idea is creating training and employment opportunities for people living in nearby shelters or on the streets.

“Let’s come up with some ideas that can actually generate revenue to help people be employed,” Constant said. At such an early stage, he said it’s not clear whether it will ultimately be a for-profit or non-profit venture. “I personally lean towards coming up with a for-profit that manages the farm and the non-profit partners that are a part of it.”

Constant said he has started conversations about the project with a number of stakeholders, including partners at the city and area non-profits, as well as with private-sector businesses like Vertical Harvest, which builds hydroponic growing systems inside shipping containers.

Jack Jack's Coffee House The 'Catalyst' For Urban Farming On Long Island

Jack Jack's Coffee House The 'Catalyst' For Urban Farming On Long Island

Jack Jack’s Coffee House in Babylon played a big role in helping bring the “Urban Farming” concept to Long Island, something that has caught the eye of local and NYC media alike.

Jim Adams of West Babylon was looking for a new way to benefit the community through the local and organic agriculture movement when he met the owners of Jack Jack’s, Mike Sparacino and Vanessa Viola.

As farmers themselves, Sparacino and Viola offered him tips to growing in the local area.

Signage that sits outside of Trimarco’s newly transformed lawn

They also helped him publicize his fledgling Long Island Farms effort and the need for volunteers.

Adams left a flier at Jack Jack’s asking people to “consider turning [their] lawn into a small local farm and at the same time eliminating landscaping expenses.”

“We are a place to share ideas that might be thinking out of the box,” said Sparacino.”So, when he put the poster up here we had a great response.”

Tilling The Lawn

Cassandra Trimarco, a physician assistant, who is a frequent customer at Jack Jack’s, was beyond excited to see the flier, being someone who was interested in growing her own food, but was restricted land-wise.

“I would grow little basil in cans, but that never worked out,” she said laughing.

After reading the ad she called immediately.

“[Jack Jack’s] was the catalyst and connection between [Lawn Island Farms] and myself,” she said.

Trimarco’s property was a perfect fit for a farm makeover.

Jim walking through his farmland at St. Peter’s Farm

And just this month, her little front-yard farm caught the attention of CBS News New York, with a Newsday report quickly following.

“On Long Island, there is now a ‘front yard to table’ effort and it’s turning heads,” CBS reported.

“We have plenty of land [on Long Island], we shouldn’t be flying in pesticide-filled [crops],” Adams told GreaterBabylon on Friday.

Trimarco moved into her Hyman Avenue house on May 1, and Lawn Island Farms immediately began the conversion process.

According to Lawn Island Farms, it took about two weeks of heavy pilling to get the initial seeds down, but now they are in harvest. Trimarco herself has no farming responsibilities, she just enjoys the view while getting $30 worth of crops per week.

“It’s great; I love it,” said Trimarco, “It’s attracting a lot of great things and it’s beautiful”

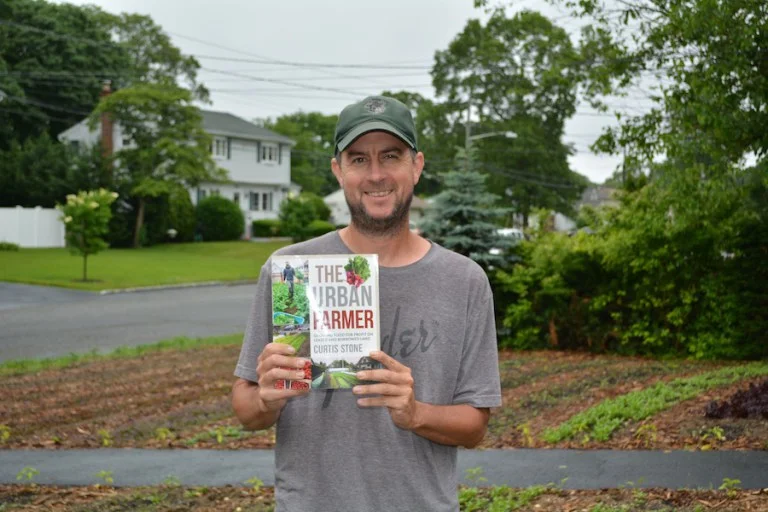

Jim Adams shows off a copy of The Urban Farmer

Lawn Island Farms takes the freshly grown produce and sells them to local businesses as well as at farmer markets in Bay Shore and Sayville.

The Movement

Jim became interested in urban farming after quitting his pool servicing job after 20 years in search of something more “meaningful.” He had read a book called The Urban Farmer, written by Curtis Stone, which gives guidelines to growing on small plots of land.

Jim and his wife, Rosette Basiima Adams, 34, soon started talking seriously about growing locally. For Rosette, who is from Uganda, she had found it odd to learn Americans didn’t grow their own food.

It wasn’t until she was 25 when she moved to the U.S. that she visited her first grocery store.

“When I first saw a supermarket I was excited and wowed,” she said. “Then I saw the food wasn’t fresh and was genetically modified.”

When Jim met with Sparacino and Viola, the first tip they were given was on a great location to start his farming.

“I recommended [Jim] to grow at St. Peter’s Farm,” said Saparcino.

St. Peter’s Farm is a small agricultural lot hidden behind by the St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Bay Shore.

Both Jim and Rosette visited the church, where they agreed to take over 10,000 square feet of land and create their Lawn Island Farms.

Rosette Basiima Adams checking on her crops outside of Trimarco’s house

“We never even knew that land was back there,” said Jim. “Who knew?”

Now, Lawn Island Farms is trying to use their first urban farm’s success story to inspire others to grow locally.

“There are a lot of people who care about where there food comes from and seek it,” said Jim. “But if more of these small farms keep growing then even people who don’t care will be provided with [fresh food].

“They deserve better… we all deserve better.”

If you’d like to support Lawn Island Farms and learn more about their journey click here.

Rosette (left), Jim (middle), and Cassandra (right) in front of her house.

Fresh radishes grown by Lawn Island Farms.

Lawn Island Farms crops at St. Peter’s Farm.

Fresh lettuce growing outside of Trimarco’s household.

St. Paul-Based Urban Organics Aims To Provide Local Greens All Year Long

St. Paul-Based Urban Organics Aims To Provide Local Greens All Year Long

June 24, 2017 12:37 PM By Rachel Slavik

Filed Under: Dave Haider, Rachel Slavik, St. Paul, Urban Organics

MINNEAPOLIS (WCCO) — Minnesota winters aren’t exactly ideal growing conditions for fresh local produce. One St. Paul company is working to bring local, organic greens to store shelves all year long.

Urban Organics is among the first to begin mass producing several varieties of lettuce within city limits prompting an agricultural evolution, of sorts.

Outdoor farming is moving inside because of people like Dave Haider.

“It’s absolutely perfect growing conditions 365 days a year,” Haider said.

Dave is the co-owner of Urban Organics, which produces locally-grown, organic leafy greens.

“I think people are starting to have a deeper focus on where their food comes from,” Haider said.

That interest has led to incredible growth since the company’s launch four years ago. Haider started with a smaller operation in the Hamm’s brewery but recently expanded to a new 90,000 square facility in the old Schmidt Brewery.

“I don’t think we anticipated such a high demand so quickly,” Haider said.

Urban Organics has found success using aquaponics and hydroponics, a process where fish and water are combined to help plants grow.

Each leafy green sprouts in nutrient filled water funneled from onsite tanks containing salmon and char.

“We capture the waste, remove the solid waste and ammonia in the water. It’s converted to nitrates through a biological filter and it’s that nitrate rich water that provides all the nutrients, all the nitrogen for the plants,” Haider said.

Dave said the end result is a growing system that uses less than five percent of water compared to conventional agriculture and ultimately allows fresh greens to reach store shelves within a day and a half.

“Very low impact on the environment,” Haider said.

The products are in most co-ops around the Twin Cities and three Lunds/Byerly’s stores. For more on where and what lettuce varieties are available, go here.

Urban Farming Won't Save Us From Climate Change

Photographer: Zoran Milich/Moment Mobile ED

Urban Farming Won't Save Us From Climate Change

Community gardens serve many purposes. Slowing climate change isn't one of them.

By Deena Shanker | June 21, 2017, 8:46 AM CDT

In places such as New York and Boston, the appeal of the self-sustaining rooftop farm is irresistible. If only enough unused space were converted to fertile fields, the thinking goes, local kale and spinach for the masses could be a reality, even in the most crowded neighborhoods.

Proponents claim that city vegetable gardens are a solution to nearly every urban woe, providing access to healthy foods in neighborhoods that lack it, as well as economic stimulation, community engagement, and significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. But a new study published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology says that in colder climates such as the Northeast's, the emissions reductions are minimal.

"Urban farming advocates tend to focus on the distance from farm to fork, equating local food with environmentally sustainable food, oversimplifying the complexity of food sustainability to a single aspect," the researchers write. In reality, the carbon reductions made possible by urban farming are much smaller than many had assumed. In the best case scenario, urban farming would only reduce a Northeastern's city's food-related carbon footprint by 2.9 percent, the study found.

The study's authors used Boston to prove their point.

They first established the city's food-related environmental impact baseline by combining publicly available dietary information with data on the burden required to supply that food. Next, they determined the space available for urban farming, including both ground lots and usable rooftop space. Finally, they used data from several farms in Boston and New York to understand the resources used, including fossil fuel-based power, the vegetables they yield, and their overall environmental impact. Ultimately, the researchers found the environmental gains from urban farming to be "marginal."

The reason is that while city-grown vegetables can have a slightly lower environmental impact than those grown thousands of miles away, horticulture has never been the real problem. It's not apples and tomatoes that are responsible for most of the diet's greenhouse gas emissions; it's animals. Meat and dairy products contribute 54 percent of the American diet's potential impact on climate change. If city residents really want to lower their carbon footprints, they should become vegan. For bonus points, they can turn their roofs into solar gardens instead of vegetable ones.

There are many reasons to embrace urban agriculture. Greater access to produce could help improve the diet of city residents, and replacing pavement with soil could help abate water runoff, for example. But slowing climate change isn't one of them. The potential economic benefits of urban farming are also less promising than proponents had hoped, the study found. Even if Boston-grown vegetables were sold within the larger metropolitan area, the value would still be less than .5 percent of regional gross domestic product. And while some of that growth would go to low-income neighborhoods, the majority would flow to areas with poverty rates below 25 percent.

"I am positive about urban agriculture," says Benjamin Goldstein, of the Technical University of Denmark and the lead author of the study. "I just want to make sure it's done for the right reasons."

City Roots Urban Farm Becomes Hub For Eat Local Movement In The Midlands

City Roots Urban Farm Becomes Hub For Eat Local Movement In The Midlands

- By Stephanie Burt Special to The Post and Courier

- Jun 18, 2017

Eric McClam at the family's City Roots urban farm in Columbia.

COLUMBIA — In 2009, when Robbie McClam and his son, Eric, started City Roots Farm, they usually had to follow an introduction by explaining that the urban property was out by the Columbia Municipal Airport. These days, there is rarely any follow-up reference needed.

City Roots has expanded into a hub of the local food movement in the capital city, providing not only fresh veggies to the chefs and farmers market shoppers in the region, but microgreens to the Southeast, a CSA for local residents, an event venue, and even a children’s day camp this summer. And they are not stopping there.

Martha and Eric McClam hold daughter, Tessa, at City Roots. She is growing up around the farm, and so are 3,000 to 4,000 children who visit each year through Richland County schools.

“Columbia is a completely different place from when I left in 2004 to when I returned in 2009,” says Eric McClam, who heads the operation that employs 20 staff members and five interns. “The arts scene and the food scene were really beginning to be intertwined, and there was a general awareness of sustainability that made us excited.”

So when McClam knocked on the kitchen door of Kristian Niemi, who was then cooking at Rosso Trattoria, to gauge the chef's interest in purchasing local products, Niemi responded with an enthusiastic yes, especially if the consistency and quality was up to high-end restaurant standards.

Thus, the McClam family had their assignment and went to work, creating a diverse farm on 3 acres that in 2018 will reach an expanded 40 acres (including land leased elsewhere in Richland County). Approximately 30 restaurants in the Columbia area use City Roots produce, including Niemi’s current flagship, Bourbon. That’s not counting the chefs outside the immediate region who have access to the products through distributors. Although City Roots produces a wide range of fruits and vegetables, from blueberries to oyster mushrooms to tomatoes and even cut flowers, its main crop is microgreens.

A view of one of the greenhouse tunnels where microgreens are grown.

“We grow 20 varieties of microgreens that are in 32 Whole Foods Markets in the Southeast, Growfood Carolina food hub in Charleston, various farmers markets we participate in, and even on Carnival Cruise Ships,” McClam explains. The greens are grown primarily in five high tunnels on the farm, and the fast-growing specialty crop provides a stable base for the farm, which allows for creativity and experimentation.

For example, in 2015, the farm installed a tilapia pond system to begin aquaponic farming on site, and after working with that for a year or so, is now transforming that pond into more of a demonstration pond for schoolchildren. They didn’t bank all their efforts on the tilapia venture being successful, so as a agribusiness, they were able to redirect efforts elsewhere. It's a nimbleness that is often lacking for single-crop farms.

Microgreens growing at City Roots farm, which has become a major supplier of the leafy produce in the Southeast.

It also allows them to take chances and have vision for the space as a unique entity beyond just crops and harvest.

“I just walked up to Eric at the farmers market one day and said, ‘I want to have a dinner on your farm,’” says Vanessa Driscoll Bialobreski, a Columbia native, event planner and public relations professional who had recently moved back to the city and was looking to get involved in the local community.

City Roots said yes, and from there, things "just blew up,” Bialobreski says. Over the past six years, at least 13,000 tickets have been sold to more than 200 events at the farm.

Bialobreski is now the managing partner for the Farm to Table Event Company, which runs those events and counts Robbie McClam and Niemi as partners as well. It has created a symbiotic relationship that continues to help all parties while at the same time creating events for the city, including a recent sold-out James Beard Foundation dinner and a Mardi Gras Festival. “It’s great for us to get involved in the community as a team and bridge that farm-to-table gap,” Bialobreski says.

City Roots has become a hub for the community, not only at farmers markets and wholesale to local chefs, but also has a gathering space for a growing number of local food-centric events.

“City Roots is such an important part of the overall food culture that is helping to put Columbia on the map as a destination,” says Kelly Barbrey, vice president of sales and marketing at Experience Columbia SC. “Many of our local restaurants are using their produce, microgreens and flowers, all of which are grown right here in the heart of the city, and local residents and out-of-towners love coming to unique events held at City Roots, like the Rosé Festival and Tasty Tomato Festival, to feel connected to the energy and vitality of our community.”

Beyond the festive events, the up to 4,000 schoolchildren who visit each year, the first annual summer day camp, and the locals who shop in the farm store, City Roots is now working to bring even more people to the farm through canning and pickling. At the moment, staff is working on building out a kitchen that will meet DHEC approval. Not only will it help the farm preserve produce that can be another specialty product, but the kitchen can be a space where people can come to learn the skills of pickling and preserving.

With the rise of the collaboration between Farm to Table Event Co. and City Roots, the farm is serving the community in multiple ways, including through special events.

It seems there’s always something “cooking” at City Roots, from the Midlands farms database they are building and sharing for area chefs to the consideration of produce being included in Blue Apron. Eric McClam and his staff are not only willing to consider new ways of bringing local produce to consumers, but are creating a more stable and sustainable regional culture through that produce.

“When we started, we were the only show in town so to speak when it came to buying local produce,” McClam says. “Now local produce, or at least the consideration, is part of people’s vocabulary. We are happy to be right at the time when Columbia caught the local food craze.”

ShopRite Expands Locally Grown Program

ShopRite Expands Locally Grown Program

JUNE 23, 2017

Continuing its long-held tradition of carrying locally grown products, ShopRite has expanded its Locally Grown program, offering a rich variety of products throughout the supermarket — from fresh fruits and vegetables to farm-raised beef, seafood, flowers, baked goods, honey, craft beer and roasted coffees.ShopRite associate Chun Hung of Cherry Hill, NJ.

ShopRite associate Chun Hung of Cherry Hill, NJ.

“ShopRite has been partnering with local farmers since our inception almost 70 years ago,” Derrick Jenkins, vice president of the produce and floral division at ShopRite, said in a press release. “But more than ever, we are meeting increased customer demand for locally sourced products by working hand-in-hand with local entrepreneurs, family farms and businesses to procure and sell products that have been locally grown.”

ShopRite recently joined state officials in announcing the debut of the “Grown in Monmouth” label. Its stores in New Jersey’s Monmouth and Ocean counties will feature flowers and plants branded with the new label and sourced from local farms.

Many seasonal and unique products can also be found on a store-by-store basis. These “hyperlocal” products are produced by local independent businesses and growers, including greens that have been grown on local hydroponic or indoor “vertical” farms.

“ShopRite is proud to work with local family farms and businesses because local is not only how we source our food, it’s who we are,” Jenkins said in the release. “We look forward to offering shoppers an ever-increasing assortment of locally made products and goods throughout the year.”

We Kid You Not: Goats Clean Up Parks and Educate Communities on Urban Farming

We Kid You Not: Goats Clean Up Parks and Educate Communities on Urban Farming

By AINE CREEDON | June 16, 2017

June 14, 2017; Denver Post

Imagine waking up on a Saturday morning to eight goats being walked on leashes down your street, heading to a local park where the honorary goat-welcoming committee awaits them. In Wheat Ridge, a western Denver suburb, this unusual landscaping goat crew turning heads is becoming a local attraction and is also educating communities on urban agriculture.

In 2013, Wheat Ridge’s Five Fridges Farm was struggling with how to address an overgrown noxious weed problem they were facing. The land was in a tough spot for lawnmower access, and chemicals simply weren’t an option for the local organic urban farm. So, Five Fridges Farm decided to bring in a group of its LaMancha male goats to the 1.5-acre enclosure, where they spent several weeks grazing on weeds.

Using goats as landscapers has become a perfect solution to their problem and they are now being brought to graze in other open spaces within the community. Due to their unique digestive systems, goats are able to consume invasive weeds without redistributing any of the seeds in their excrement. As the weeds are removed, the goats enjoy a nutritious meal, and the land also further benefits from fresh manure for fertilization.

Amy Weaver, owner of Five Fridges Farm, says the most surprising outcome of the project has been the community support that has erupted. Over the past few years, the goats have become a big hit with local residents, which flock to visit the hard workers cleaning up their parks.

This is the fourth year the Wheat Ridge community has successfully used LaMancha goats to manage invasive weeds and vegetation in natural areas, and these popular yearly visitors are providing a great opportunity to educate the community about urban farming. “People have big questions about their food system. This is a place where people can ask questions without judgment,” Amy Weaver explained. “The money from the products isn’t what fuels the farm. It’s the education that comes from it.”—Aine Creedon

ABOUT AINE CREEDON

Aine Creedon is Nonprofit Quarterly's Digital Publishing Coordinator and has worn many hats at NPQ over the past five years. She has extensive experience with social media, communications and outreach in the nonprofit sector, and spent two years in Americorps programs serving with a handful of organizations across the nation. Aine currently resides in Denver, Colorado where she enjoys hiking with her dog Frida and is currently serving on the advisory board of the Young Nonprofit Professionals Network Denver and also co-leads their Marketing and Communications Committee.

What Makes Urban Food Policy Happen? Insights From Five Case Studies

What Makes Urban Food Policy Happen? Insights From Five Case Studies

NEW REPORT: What Makes Urban Food Policy Happen? Insights From Five Case Studies

(Brussels / Stockholm: 12th June) Cities are rising as powerful agents in the world of food, says a new report from the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food), and they are finding innovative ways to put in place policies that take on challenges in global food systems.

The report, presented today at the EAT Stockholm Food Forum by lead author Corinna Hawkes, Director of the Centre for Food Policy at City University (London), shows that food policy is no longer the domain of national governments alone.

"Cities are taking matters into their own hands to try to fix the food system," said Hawkes. "Hundreds of cities around the world are taking concerted policy action — whether it be to ensure access to decent, nutritious food for all, to support farm livelihoods or to mitigate climate change."

The new report, entitled ‘What makes urban food policy happen? Insights from five case studies’, draws lessons from the ways in which five cities around the world have developed urban food policies:

- Belo Horizonte's approach to food security (Brazil) was one of the first integrated food security policies in the world, and the dedicated food agency within city government has survived for over 20 years.

- The Nairobi Urban Agriculture Promotion and Regulation Act (Kenya) represents a U-turn on long-standing opposition to urban farming from city authorities. The 2015 legislation came on the back of civil society advocacy and a window of opportunity opened by constitutional reform in Kenya.

- The Amsterdam Approach to Healthy Weight (the Netherlands) requires all city government departments to contribute to addressing the structural causes of childhood obesity through their policies, plans and day-to-day working.

- The Golden Horseshoe Food and Farming Plan (Canada) involved establishment of an innovative governance body to promote collaboration between local governments within a city region, and other organizations with an interest in the food and farming economy.

- Detroit's Urban Agriculture Ordinance (US) required the City of Detroit to negotiate over State-level legislative frameworks so as to have the authority to regulate and support urban farming, a burgeoning activity in the city.

Although these policies were all developed and delivered in very different contexts, the report's authors identified a number of factors that, time and again, were seen to drive policy forward.

Whether the policies were initiated from the top down or from the bottom up, the cases showed that an inclusive process as the policy moves forward — involving communities, civil society and actors from across the food system — is what matters most, helping to align policies with needs and creating a broad support base to help with implementation.

The examples also showed that even when policies are initially framed around a limited set of priorities, there is much scope for bringing other departments on board and expanding the ambitions along the way.

Identifying the precise policy powers cities can draw on to address the food challenges at hand — and leveraging these powers to the max — also proved crucial in several cases. This meant they could focus resources on areas where change could be achieved most effectively and cheaply.

"The cities we studied were tremendously innovative when it came to harnessing the factors that drive policy forward, and overcoming the barriers," said Hawkes. "They found ways of extending budgets to enable full implementation of the policy, institutionalizing policies to help them transcend electoral cycles, and even obtaining new powers if they did not have the authority to develop and deliver the policy they wanted."

"Sharing these experiences is crucial. Looking at what has been done elsewhere can help cities of all sizes — from small towns that are taking their first steps in designing food-related policy, to big cities that are striving to maintain highly-developed, integrated policies — that are working to improve their food systems".

Read The Executive Summary

Read The Complete Report Here

Cincinnati City Council Hopes To Turn Vacant, Blighted Properties Into Urban Farms

Cincinnati City Council Hopes To Turn Vacant, Blighted Properties Into Urban Farms

Amanda Seitz | 6:46 AM, Jun 15, 2017

CINCINNATI -- What if rotting, vacant homes and abandoned, overgrown lands in some of the city's neighborhoods were transformed into urban farms growing fresh produce?

Cincinnati City Council is considering a new pilot program that could flip as many as 10 vacant parcels of land into gardens ready for planting anything from herbs to cucumbers.

Supporters believe the humble start to this project could ultimately alleviate some of the city’s most stubborn problems: food deserts, unemployment and blight.

“It will assist in taking that blight, that was a negative, and not only improving the look, but providing sustenance to the area as well,” said Cincinnati City Councilman Kevin Flynn, who proposed the program.

City crews have struggled to keep up with mowing and weeding the more than 1,000 properties – some of them condemned or abandoned by their owners, Flynn said.

That leaves neighbors frustrated with unkempt eyesores that abut their homes.

Flynn believes unkempt city-owned properties like these could see new life as urban farms. Photo by David Sorcher | WCPO contributor

“It got me thinking: Rather than it being a burden on the city to have to pay to maintain these spots … let’s give them to somebody that will maintain them and how about we plant some fruits and vegetables in these vacant spots?” Flynn told WCPO in an interview last week.

The motion he wrote calls for the city to develop a plan to convert urban farms on city-owned land, identify potential properties, and look into any costs the city might have to consider when launching the program.

His proposal passed with the full support of council earlier this month.

WCPO Insiders will learn how similar programs have worked in other cities, areas of Cincinnati where this development might occur and how it might be funded.

Plantagon Announces its 40th Approved Patent

Plantagon Announces its 40th Approved Patent

News • Jun 16, 2017 10:18 GMT

Plantagon World Food Building in Linköping. Standard Patent Certificate for Australia. The uPot

Developing and expanding the Intellectual Property Portfolio is an important corporate strategy for the Sweden based innovation company Plantagon International, with recent patents granted in the US, China and Australia.

"R&D and the resulting technological innovations are the principal factors for Plantagon International’s business success. Plantagon International’s innovation strategy involves benefiting from technological innovations by using the full range of intellectual property rights in the development of urban agriculture”, says Owe Petersson, CEO of Plantagon.

The company’s most recent patents are: in the USA: Methods and arrangements for growing plants; in China: The uPot; and in Australia: Building for cultivating crops in trays. There are still 28 pending patents.

"It is with great pleasure I follow the progress of the Plantagon Intellectual Property Portfolio. Pending patents get granted without major objections from local patent authorities. This means our inventions have inventive step, novelty and usefulness", says Joakim Rytterborn, Research & Development Manager at Plantagon.

Four patent families

Plantagon currently has filed for patents within four patent families:

- Conveying system, tower structure with conveying system, and method for conveying containers with a conveying system

- Building for cultivating crops in trays, with conveying system for moving the trays

- Method and arrangement for growing plants

- Pot device and method related thereto

Asia

Last year Singapore, as the first country, granted a patent from Plantagon’s fourth patent family, the uPot, and this year this patent for the uPot was granted in China. The uPot solves the problem with spacing the plants during growth. This by an adjustable distance ring, which enables spacing in two dimensions and hence is about 20 percent more effective than other methods on the market.

Africa

Recently Plantagon also was granted its first ARIPO Patent (African Regional Intellectual Property Organization). Regarding this Mats Lundberg CEO of Sweden’s oldest IP-firm Groth says:

“Plantagon is a company in the very forefront in terms of both innovation and IP. This recently granted patent is further evidence of this. Africa, for example, is a continent often overlooked when companies strive for global IP protection. But it is an emerging market important to consider. Also, thanks to the African Regional Intellectual Property Organization, ARIPO, foreign companies can now apply for a unified patent in a cost-efficient way in 19 African states.”

"Plantagon started with an idea from a Swedish gardener. If you have any great ideas that will make the world a better place, join Plantagon and develop them together with us,” says Joakim Rytterborn.

---

Plantagon International is a world-leading pioneer within the field agritechture and social entrepreneurship – combining urban agriculture, innovative technical solutions and architecture – to meet the demand for efficient food production within cities; adding a more democratic and inclusive governance model. We see global corporate governance, food security and sustainable food production as among the most critical areas for the future of our planet. Plantagon’s objective is to inspire a value change for survival and meet the rising demand for locally grown food in cities around the world, minimizing the use of transportation, land, energy and water. www.plantagon.com & www.plantagon.org