Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

USA: Zenat Begum Turned A Bustling Brooklyn Street Corner Into A Working Greenhouse

She reached out to Jasper Kerbs of the Cooper Union Garden Project and, with the help of several volunteers, the structure was erected in October of last year. The shop is utilizing one of the city’s outdoor vending permits and they’re in the midst of harvesting this month

The owner of Playground Coffee Shop transformed the cafe’s outdoor dining space into a project centered around care, creativity, and community

April 21, 2021

“I’m inviting people that I love to come and dress up the facade,” Zenat says of the greenhouse's verdant mural by artist Tiffany Baker. “I’m inviting people that I really respect to come and build these things because we deserve the best.”Image courtesy of Zenat Begum

To understand how a fully functioning greenhouse ended up at the busy intersection of Quincy Street and Bedford Avenue in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, it’s important to get to know Zenat Begum, the owner of Playground Coffee Shop.

Zenat opened the shop back in 2016, in a space that previously housed her father’s hardware store, and quickly expanded to include the Playground Annex, which houses a radio station and bookstore, as well as Playground Youth, a nonprofit organization dedicated to issues confronting the community, including literacy and food equity.

“I believe in Bed-Stuy. I believe in myself. I believe in the shop. I believe in the greenhouse,” says Playground Coffee Shop owner Zenat Begum. “These are things that are active radical attempts. We are imagining our futures because these things aren’t going to be built for us.”Image courtesy of Zenat Begum

Providing for the community is fundamental to each project that the Playground team takes on. “Every time we do something, we change and raise the bar of what should be done in our communities,” Zenat explains. “I’m talking about being able to keep implementing this really large notion and understanding of entrepreneurship into taking care of your communities.”

Shortly after the pandemic hit, Playground got to work on several mutual aid projects. The team established a take-one-leave-one library that distributes works exclusively by writers of color, assembled a network of volunteers distributing PPE and essential supplies at Black Lives Matter protests, and they worked with organizers to create a network of community fridges providing free produce 24 hours a day.

It was while working on the fridge project that the idea for the greenhouse began to crystalize, in realizing that fundamentally addressing the issues surrounding food sovereignty wasn’t, as she says, “as simple as just donating a fridge.”

Zenat cites the statistics: One in three kids in New York City are food insecure, and one in 10 in public schools experience homelessness. She probed further, looking at obesity and food deserts and gentrification. “Let’s reel it back: Why aren’t there programs that support Black and brown families who can’t support their children with adequate nourishment and nutrition?”

“It made me really frustrated. We need to have a plot of land that grows for this. We need to get an actual farm to be able to grow food for this,” Zenat says. And never having built a greenhouse before didn’t scare her off. “I don’t really have the tools,” she thought. “But I also know that, for the understanding that I have and the experience that I’ve had growing up in New York, I know what a New Yorker deserves, which is a lot more.”

She reached out to Jasper Kerbs of the Cooper Union Garden Project and, with the help of several volunteers, the structure was erected in October of last year. The shop is utilizing one of the city’s outdoor vending permits and they’re in the midst of harvesting this month.

When they’re able to resume programming, Zenat intends to teach kids in the neighborhood how to get involved and have plots so they can start growing together. “The most important thing about this is that this will be an opportunity for kids who live in Bed-Stuy to see food growing, to show them that there is life that starts at fertilizing and that we can be involved in the process of food distribution and food harvesting from the very beginning.”

“Our greenhouse is straight up on the street. I want people to see that these structures have to and should exist.”Image courtesy of Zenat Begum

And she acknowledges the responsibility and history that comes with this endeavor. “We’re on stolen land right now,” Zenat says. “We’re thinking about farming practices that date back to East Asia, which is where my family is from, and sharecropping that was implemented during the period just after slavery, which is one of the darkest times in history, period. But with all of those tragedies and travesties occurring, there is this sense of land and relationship that we have that we need to bring back to ourselves. It’s ancestral, of course, and it’s spiritual, but most importantly it’s territorial. Why is it that Black and brown people have a hard time with housing and food insecurity when we have literally created some of the most adequate and sophisticated food systems in the world? Our bodies are used to actually supply people with this type of food and nourishment.”

“So there’s many things that we’re addressing here, but I only hope that at surface level we’re talking about things that actually make a difference, which is ultimately feeding children.”

In true Playground style, the greenhouse is one of many initiatives in the works—from financial literacy courses and book clubs to bystander intervention trainings. Given Zenat’s dedication, there’s no doubt they’ll come to fruition. “The way that I love New York is so poetic. I’m like one of those gnarly girlfriends, ‘Did you eat today? Do you want water?’” She asks the city: “Did you eat today, New York? Do you want water? Do you want a pillow?”

If you’d like to support Playground Youth, there is a fundraiser underway for programming and operational costs.

Turning Empty Spaces Into Urban Farms

With a lower occupancy rate in both retail and office spaces, property developers probably could redevelop the buildings for another usage – urban or vertical farming as done in Singapore with tremendous success

EVEN as many ordinary Malaysians struggle to make ends meet arising from the Covid-19 pandemic, empty shop lots continue to mount along the streets and some even display signs that say “available for rent”.

With the growing importance of food self-sufficiency, now is the time for Malaysia to turn empty spaces into urban farms – tackling food security-related issues besides making good use of the existing sites.

Urban farming is the practice of cultivating, processing and distributing food in or around urban areas.

Although Malaysia is rich in natural resources, we are highly dependent on high-value imported foods. Presently, our self-sufficiency level for fruits, vegetables and meat products stands at 78.4%, 44.6% and 22.9%, respectively.

With a lower occupancy rate in both retail and office spaces, property developers probably could redevelop the buildings for another usage – urban or vertical farming as done in Singapore with tremendous success.

According to the National Property Information Centre, the occupancy rate for shopping malls in Malaysia has dropped consecutively for five years. It declined from 79.2% in 2019 to 77.5% in 2020, the lowest level since 2003.

Penang recorded the lowest occupancy rate at 72.8%, followed by Johor Baru and Kuching (75.3%), Selangor (80%), Kuala Lumpur (82%), and Kota Kinabalu (82.1%).

In addition, the Valuation and Property Services Department revealed a lower occupancy rate at Malaysia’s privately-owned office buildings compared to the pre-pandemic era.

For instance, Johor Baru recorded the lowest occupancy rate of privately-owned office buildings at 61.9%, followed by Selangor (67.5%), the city centre of Kuala Lumpur (77.8%), Penang (79.8%), Kota Kinabalu (86.5%), and Kuching (87.1%).

Aquaponics – pesticide-free farming that combines aquaculture (growing fish) and hydroponics (growing plants without soil) – would be the way forward.

To summarise, aquaponics is one of the soilless farming techniques that allow fish to do most of the work by eating and producing waste. The beneficial bacteria in the water will convert waste into nutrient-rich water and is fed into the soil-less plants.

Following are the steps for vertical aquaponic farming:

1. Small growth cups are filled with coco peat, which are then sterilised under ultraviolet light, preventing bacteria and viruses from entering into the water pumps. There is an additional control over the environment with regard to temperature and daylight through the use of LED growth lights.

2. A hole is poked in the middle of the cup, where a plant seed is placed inside. The use of non-genetically modified organism seeds, where the majority are imported from reliable sources, is very much encouraged.

3. The seed is germinated for one to three days in a room.

4. Once the seed has germinated and grown to about two centimetres, the pots can be placed in the vertical harvest tower.

5. Nutrient-filled water from the fish pond flows to the plants automatically. Big plants grow within 30 days.

While enabling the growth of many varieties of vegetables with indoor temperature conditions, aquaponics can generate fish production, sustaining economic livelihoods particularly for the underprivileged and disabled communities, as well as fresh graduates who are still struggling to secure a decent job.

Although Sunway FutureX Farm, Kebun-Kebun Bangsar, and Urban Hijau, for instance, are good urban farming initiatives in the city centre of Kuala Lumpur, there are still many potential sites that could be transformed into urban farms.

Therefore, Malaysia perhaps can adopt Singapore’s approach by using hydroponics on roofs of car park structures and installing urban farms into existing unutilised buildings.

As it requires only a quarter of the size of a traditional farm to produce the same quantity of vegetables, the vertical rooftop system would yield more than four times compared with conventional farming. At the same time, it also reduces the need to clear land for agricultural use while avoiding price fluctuation.

Besides reducing over-reliance on imports and cutting carbon emissions, indoor vertical farming within the existing building also allows local food production as part of the supply chain.

It could expand into workshops, demos and expos besides offering guided and educational tours that promote the joy of urban farming.

Through urban farming structure inside a building, stressed-out office workers and the elderly, in particular, can enjoy a good indoor environment, air quality and well-ventilated indoor spaces. They can also relax their mind through gardening and walking around urban farms.

To increase the portion of food supplied locally, the government needs to empower farmers and the relevant stakeholders, incentivising the private sector in urban farming and providing other support through facilitating, brokering and investing.

This in turn would enhance the supply and affordability of a wide range of minimally processed plant-based foods as suggested under the latest Malaysia Economic Monitor “Sowing the Seeds” report by the World Bank.

With the current administration’s laudable commitment to tackling food security-related issues, this would provide an opportunity for Malaysia to review the current national food security policy by addressing productivity, resources optimisation, sustainable consumption, climate change, water and land scarcity.

By putting greater emphasis on urban farming, the government could empower farmers to plant more nutritious, higher-value crops; to improve their soil through modern technologies application (i.e., Internet of Things, Big Data and artificial intelligence); and to benefit from increased opportunities by earning higher returns on their generally small landholdings.

The government could also provide seeds, fertilisers and pesticides-related subsidies paid directly to the urban farmers through a voucher system.

For instance, the urban farming operators could use the voucher to buy high-quality seeds from any vendor or company.

The vendor also can use the voucher to claim payment from the government.

Not only would this approach create healthy competition among vendors, but it would also stimulate agricultural activities.

And given that current youth involvement in the agriculture sector is only 240,000 or 15% of total farmers in Malaysia as noted by Deputy Minister of Agriculture and Food Industries (Mafi) I, Datuk Seri Ahmad Hamzah, Mafi, the Ministry of Entrepreneur Development and Cooperatives and Ministry of Youth and Sports have to craft training programmes and develop grant initiatives together – attracting the younger generation of agropreneurs to get involved in urban farming.

These ministries can also work with the Department of Agriculture, Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute, and Federal Agricultural Marketing Authority to develop more comprehensive urban farming initiatives.

While providing job opportunities for youths to embark on urban farming, young agropreneurs can enjoy higher income and productivity, and yields, on top of increasing the contribution of agriculture to the gross domestic product.

For urban farming to thrive in Malaysia, the government perhaps can adopt and adapt the Singapore government’s approach: developing specific targets to encourage local food production.

Even though Singapore has limited resources, it is still setting an ambitious target – increasing the portion of food supplied locally to 30% by 2030.

The upcoming 12th Malaysia Plan also will provide timely opportunities for the government to turn empty spaces into urban farming in the context of the ongoing impact of Covid-19 besides fostering agricultural modernisation by leveraging on Industrial 4.0.

In a nutshell, every Malaysian can do their part to help Malaysia become more food resilient. By converting empty spaces into urban farms, it can reduce food waste, encourage local products purchase and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Amanda Yeo is a research analyst at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research. Comment: letters@thesundaily.com

Three Ways Singapore Is Designing Urban Farms To Create Food Security

Securing food during a crisis and preserving land for a livable climate is changing the focus of farming from rural areas to cities

FARMING IN THE CITY

Urban farming in Singapore

How Singapore has stimulated innovation in urban farming on a massive scale

By Clarisa Diaz | Things Reporter

March 31, 2021

Securing food during a crisis and preserving land for a livable climate is changing the focus of farming from rural areas to cities. At the forefront of this shift is Singapore, a city-sized country that aims to produce 30% of its own food by 2030. But with 90% of Singapore’s food coming from abroad, the challenge is a tall order. The plan calls for everyone in the city to grow what they can, with government grants going to those who can use technology to yield greater amounts.

“This target took into consideration the land available for agri-food production and the potential advances in technologies and innovation,” said Goh Wee Hou, the director of the Food Supply Strategies Department at the Singapore Food Agency. “Local food production currently accounts for less than 10% of our nutritional needs.”

The food items with potential for increased domestic production include vegetables, eggs, and fish. According to the Singapore Food Agency, these three types of goods are commonly consumed but are perishable and more susceptible to supply disruptions. Alternative proteins such as plant-based and lab-grown meats could also contribute to the “30 by 30” goal. In 2020, there were 238 licensed farms in Singapore.

Only 1% of Singapore’s land is being used for conventional farming. That created the constraint of growing more with less. The government has put its hopes in technology, stating that multi-story LED vegetable farms and recirculating aquaculture systems can produce 10 to 15 times more vegetables and fish than conventional farms.

Since 2017, land has been leased in two districts on the edge of the city—Lim Chu Kang and Sungei Tengah—to large-scale commercial farm projects. While the optimization of these farms to produce at maximum capacity is being determined, the idea of growing food in the more urban spaces of Singapore has emerged: from carpark rooftops to reused outdoor spaces and retrofitted building interiors.

Urban farms in Singapore

Urban farms using hydroponics on parking structure roofs

Citiponics is one of Singapore’s first rooftop farms. The hydroponic farm is on top of a carpark, a structure that services almost every neighborhood in Singapore.

Read more: How a parking lot roof was turned into an urban farm in Singapore

Installing urban farms into existing buildings

Sustenir Agriculture has created an indoor vertical farm that can retrofit into existing buildings (including office buildings). The company grows foods that can’t be produced locally, displacing imports and cutting carbon emissions.

Read more: The indoor urban farm start up that’s undercutting importers by 30%

Building a better greenhouse for urban farms in tropical climates

Natsuki’s Garden is a greenhouse in the center of the city, occupying reused space in a former schoolyard. The greenhouse is custom designed for the tropical climate to allow for better air circulation. Yielding 60-80 kg of food per square meter, the greenhouse caters to a small local market.

Read more: How a Singaporean farmer is building a better greenhouse for tropical urban farming

High production urban farms still need to be sustainable

Open to applications later this year, a new $60 million government fund will provide funding for more agritech businesses. According to the Singapore Food Agency, the fund will assist with start-up costs catering to large-scale commercial farms, no matter the location.

But as Singapore tries to advance, there are some left behind. The traditional farms that do exist in Singapore are being displaced, their knowledge no longer valued because they are not seen as hi-tech, according to Lionel Wong, the founding director at Upgrown Farming Company, a consultancy that helps equip new farming business owners across Singapore. “While we are trying to increase production, the net result could actually be reduced production because the traditional growers are being removed from the equation in the long term.”

In the long-run, high production of food within Singapore will need a sustainable market of consumers, to Wong that market isn’t completely clear at the moment. “‘30 by 30’ is really just a vision. The Food Agency deserves a lot of credit in terms of what they’re trying to push, but there’s a lot of room for improvement.” Wong continued, “productivity doesn’t necessarily equate to sustainability or profitability.”

Whether Singapore is able to produce its own food sustainably for the long-run remains to be seen. But the endeavor is certainly an exciting moment for entrepreneurs pushing the boundaries of what farming and cities can be.

Lead photo: COURTESY CITIPONICS | Singapore aims to produce 30% of its food by 2030.

This Vertical Farming System Was Designed To Build Up Community And Accommodate The Urban Lifestyle!

Urban farming takes different shapes in different cities. Some cities can accommodate thriving backyard gardens for produce, some take to hydroponics for growing plants, and then some might keep their gardens on rooftops

03/19/2021

Following interviews with local residents, Andersson set out to create a farming system that works for the city’s green-thumb community.

Urban farming takes different shapes in different cities. Some cities can accommodate thriving backyard gardens for produce, some take to hydroponics for growing plants, and then some might keep their gardens on rooftops. In Malmö, small-scale farming initiatives are growing in size and Jacob Alm Andersson has designed his own vertical farming system called Nivå, directly inspired by his community and the local narratives of Malmö’s urban farmers.

Through interviews, Andersson learned that most farmers in Malmö began farming after feeling inspired by their neighbors, who also grew their own produce. Noticing the cyclical nature of community farming, Andersson set out to create a more focused space where that cyclical inspiration could flourish and where younger generations could learn about city farming along with the importance of sustainability.

Speaking more to this, Andersson notes, “People need to feel able and motivated to grow food. A communal solution where neighbors can share ideas, inspire and help one another is one way to introduce spaces that will create long-lasting motivation to grow food.”

Since most cities have limited space available, Andersson had to get creative in designing his small-scale urban farming system in Malmö. He found that for an urban farm to be successful in Malmö, the design had to be adaptable and operable on a vertical plane– it all came down to the build of Nivå.

Inspired by the local architecture of Malmö, Andersson constructed each system by stacking steel beams together to create shelves and then reinforced those with wooden beams, providing plenty of stability. Deciding against the use of screws, Nivå’s deep, heat-treated pine planters latch onto the steel beams using a hook and latch method. Ultimately, Nivå’s final form is a type of urban farming workstation, even including a center workbench ideal for activities like chopping produce or pruning crops.

Taking inspiration from community gardens and the local residents’ needs, Andersson found communal inspiration in Malmö.

Backyard and patio gardens are popular options for those living in cities who’d still like to have their very own gardening space.

Lead photo: Designer: Jacob Alm Andersson.

Kalera Announces Newest Vertical Farming Facility To Open In St. Paul, Minnesota

With millions of heads of lettuce to be grown per year, Kalera’s St. Paul facility will provide a source of fresh, non-GMO, clean, living lettuces and microgreens to retailers, restaurants and other customers. Kalera’s location in the heart of the city will shorten travel time for greens from days to mere hours, preserving nutrients, freshness, and flavor

The New Facility Will Provide Fresh,

Hydroponically-Grown Produce To The Western Midwest

ORLANDO, Fla., March 15, 2021 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Kalera (Euronext Growth Oslo ticker KAL, Bloomberg: KSLLF), one of the fastest-growing US vertical farming companies in the world and a leader in plant science for producing high-quality produce in controlled environments, today announced the purchase of a facility in St. Paul, Minnesota which they will convert to a vertical farming facility. Kalera’s Minnesota location is the eighth facility it has announced, making it one of the fastest-growing vertical farming companies in the United States. This announcement comes on the heels of the news of Kalera’s appointment of Sonny Perdue, former Secretary of Agriculture and Maria Sastre to the Board of Directors, as well as its acquisition of Vindara, the first company to develop seeds specifically designed for use in vertical indoor farm environments as well as other controlled environment agriculture (CEA) farming methods.

With millions of heads of lettuce to be grown per year, Kalera’s St. Paul facility will provide a source of fresh, non-GMO, clean, living lettuces and microgreens to retailers, restaurants and other customers. Kalera’s location in the heart of the city will shorten travel time for greens from days to mere hours, preserving nutrients, freshness, and flavor. The facility will also generate approximately 70 jobs upon opening.

“I’m proud to be welcoming Kalera to St. Paul and the W. 7th neighborhood,” said City Councilmember Rebecca Noecker, who represents St. Paul’s Ward 2. “The facility is not only bringing millions of dollars in investment into the community but is also providing jobs and importantly, increasing access to fresh, non-GMO, clean, locally grown produce.”

Kalera currently operates two growing facilities in Orlando and last week started operations in its newest and largest facility to date in Atlanta and is building facilities in Houston, Denver, Columbus, Seattle, and Hawaii. Kalera is the only controlled environment agriculture company with coast-to-coast facilities being constructed, offering grocers, restaurants, theme parks, airports and other businesses nationwide reliable access to locally grown clean, safe, nutritious, price-stable, long-lasting greens. Once all of these farms are operational, the total projected yield is several tens of millions of heads of lettuce per year, or the equivalent of over 1,000 acres of traditional field farms. Kalera uses a closed-loop irrigation system which enables its plants to grow while consuming 95% less water compared to field farming.

“Minnesotans are all too familiar with the limitations of a challenging climate,” said Daniel Malechuk, Kalera CEO. “They also take great pride in local accomplishments, so we are extremely excited to facilitate this opportunity for Minnesotans to have fresh, high quality produce year-round, grown by the locals for the locals.”

Final project commitments, including jobs and capital investment, are contingent on final approval of state incentives.

ABOUT KALERA

Kalera is a technology-driven vertical farming company with unique growing methods combining optimized nutrients and light recipes, precise environmental controls, and cleanroom standards to produce safe, highly nutritious, pesticide-free, non-GMO vegetables with consistently high quality and longer shelf life year-round. The company’s high-yield, automated, data-driven hydroponic production facilities have been designed for rapid rollout with industry-leading payback times to grow vegetables faster, cleaner, at a lower cost, and with less environmental impact.

Stockholm’s Indoor Farms Boost Food Security

The city is revolutionizing its food sector by showing results in eco-friendly urban farming

The City Is Revolutionizing Its Food

Sector By Showing Results

In Eco-Friendly Urban Farming

14 Mar 2021

In April 2020, the UN warned that the world was on the brink of a catastrophic famine.

It was estimated that about 135 million people in around 55 countries faced shortages in food, particularly nutritious food, in 2019.

Against this backdrop, the UN has set an ambitious goal to ensure food security and wipe out hunger by 2030. It estimated that around 183 million people could slide into starvation and malnutrition if stricken with a pandemic akin to Covid-19. The coronavirus crisis disrupted global food supply chains, leading to chronic shortages in many countries.

Even before this pandemic, the ecological costs of food production were rising, compounded by water scarcity in many places. Irrigation accounts for about 70% of freshwater withdrawals around the world, with the figure reaching 90% in some developing countries.

Food production, which is critical for survival, affects the ecosystem. With the Earth’s resources depleting every day and the world population growing, we must discover innovative ways to cultivate food. We need ground-breaking and resourceful approaches to not only feed the world’s population but to do so in eco-friendly ways.

Faced with this dilemma, we need to develop alternative methods of farming, particularly using artificial intelligence.

Stockholm’s modern indoor farming methods provide some answers on how to overcome global food shortages. The city is revolutionizing its food sector by showing results in eco-friendly urban farming.

Some buildings in Stockholm incorporate artificial intelligence and eco-friendly methods into indoor farming. Circular energy wastewater and carbon-absorbing mechanisms enable indoor-grown greens while reducing the ecological footprint.

Indoor farming in Stockholm uses LED lighting and hydroponic watering systems. Food, especially vegetables, is grown indoors all year round. Growing vegetables indoors not only cuts reliance on food imports but also makes cities self-sufficient in food.

More than 1.3 million plants are grown indoors in Stockholm every year. Indoor farming has allowed Sweden to slash food imports by 60% and cut carbon emissions incurred in transporting food. Such transport accounts for a quarter of emissions in Sweden.

In some Stockholm suburbs, bright LED lights illuminate a business space. In this building, plants follow an artificial daylight rhythm to grow as efficiently as possible. Delicate plants such as various herbs and lettuce grow in stacks of about 20 metres wide by six metres high. Local restaurants, supermarkets and airlines buy this indoor-grown indoors.

Weather conditions in Sweden allow open-air farming for only three to four months a year. But climate is not a constraint in indoor farming, which maximises the use of space using stacks. Each shelf has its own LED lighting and circulating water. Even fruits like strawberries can be grown throughout the year.

Sweden Foodtech, a government agency, acts as a catalyst in promoting and encouraging innovation in the food sector. This agency also offers support to firms that want to restructure the food ecosystem. Companies converge when business events are organized focusing on major themes revolving around the future of the Swedish food sector.

Besides Sweden Foodtech, the Stockholm Business Region, a business promotion agency, aims to create a resilient food ecosystem for innovative businesses. Its goal is to position Stockholm as a “leading food-tech hub” for 300 companies in the food-tech industry.

Public interest, environmental consciousness, and an innovative society has made Stockholm a conducive place for food-tech initiatives. Consumers in this city are more ecologically vigilant, and many of them feel it is their moral obligation to support eco-friendly products. The city itself also extends support to all kinds of sustainable projects.

As a society grows more affluent, it places greater emphasis on health issues and ecological considerations. Ecological degradation and the use of harmful chemical fertilisers and pesticides will spur demand for eco-friendly and healthier food products.

Some 55% or 4.3 billion of the global population of 7.8 billion are urban dwellers. This figure could reach 70% or 6.8 billion of the world’s population of 9.7 billion by 2050.

High-tech vertical farms offer alternative ways to grow food on a large scale. In this way, we can grow our food in more energy-efficient and healthier ways. Despite developments in agricultural technology, conventional farming faces problems such as pests, climate change, and natural disasters.

With the scarcity of arable farming land, ecological problems, and health hazards, the trend is towards indoor food cultivation. The only challenge is to reduce the cost of indoor farming, especially for urban dwellers in less affluent countries.

But with technology rapidly advancing along with ongoing R&D and innovation, costs will fall, allowing economies of scale in indoor farming. Technological advances will lower costs, enhance quality and improve harvests, all of which will provide better returns on investments.

The trend towards indoor vertical hydroponic or aeroponic farming will gain momentum, especially in urban areas. Mass food production in the future will probably focus on indoor farming in buildings rather than horizontal farming on the ground.

READ MORE: Use idle city land to grow food

What’s in it for Malaysia? Our total agricultural imports reached nearly $18.3bn in 2019, roughly 7% from the US. We must slash this high import bill.

The government should encourage more Malaysians to enter the food ecosystem and develop the sector completely along the value chain. It should give incentives to unemployed graduates, especially those in relevant disciplines, to venture into the food sector. It should encourage them to get involved in R&D, integrated farming, indoor farming, manufacturing, logistics, marketing and distribution.

If there is anything we can learn from the coronavirus pandemic, it is that we have to ensure food self-sufficiency. We saw how the pandemic severely disrupted global food supply chains, and so our national agenda should prioritize food security.

Thanks for dropping by! The views expressed in Aliran's media statements and the NGO statements we have endorsed reflect Aliran's official stand. Views and opinions expressed in other pieces published here do not necessarily reflect Aliran's official position.

Our voluntary writers work hard to keep these articles free for all to read. But we do need funds to support our struggle for Justice, Freedom and Solidarity. To maintain our editorial independence, we do not carry any advertisements; nor do we accept funding from dubious sources. If everyone reading this was to make a donation, our fundraising target for the year would be achieved within a week. So please consider making a donation to Persatuan Aliran Kesedaran Negara, CIMB Bank account number 8004240948.

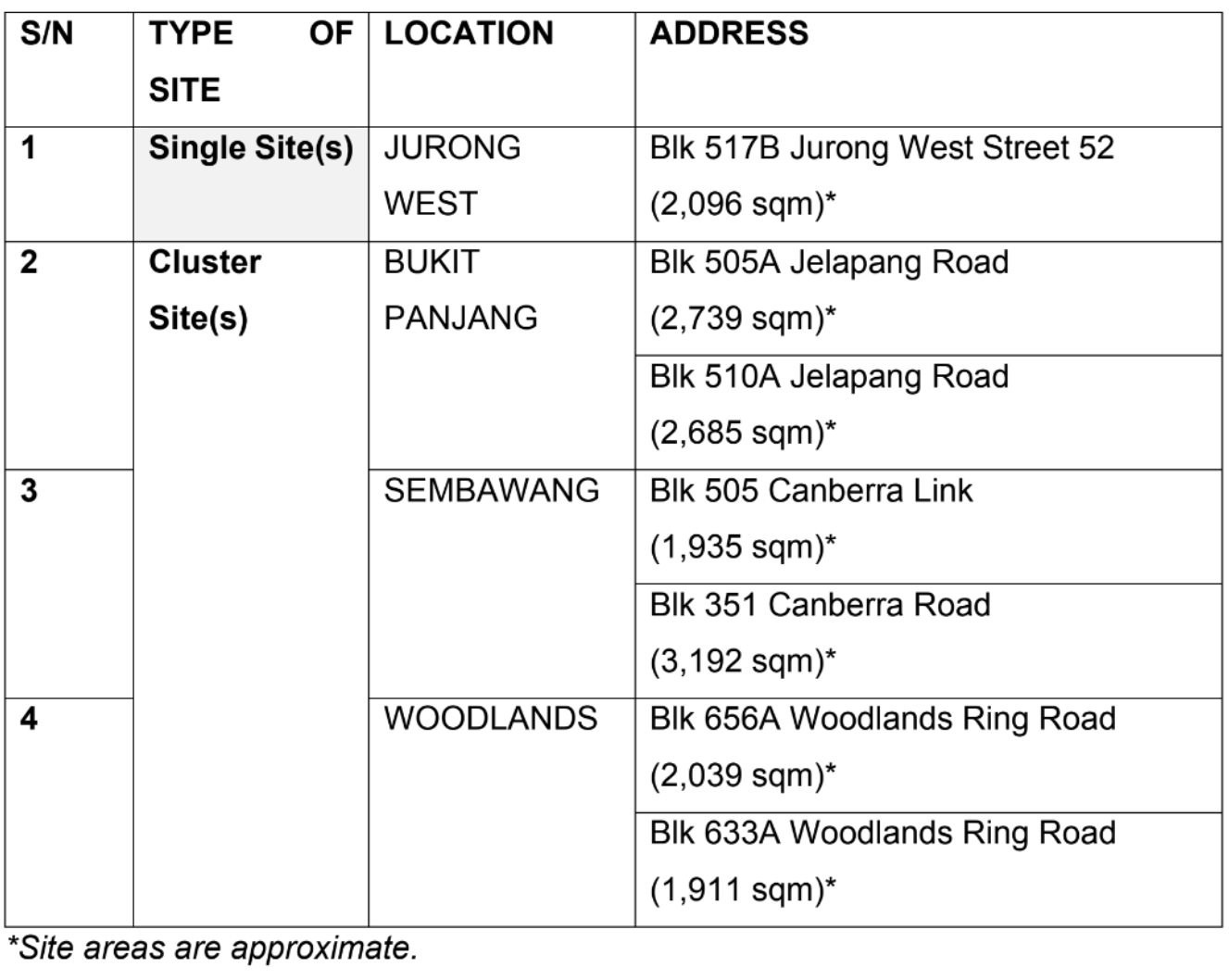

7 New HDB Carpark Rooftop Sites Offered For Rental For Urban Farming In Public Tender

More local produce. Part of Singapore's efforts to strengthen its food security is increasing its capability to produce food locally

Part of Singapore's efforts to strengthen its food security is increasing its capability to produce food locally.

To do this, more sites for urban rooftop farms atop multi-storey Housing Development Board (HDB) carparks are being offered for rental, via a public tender process that was launched today (Feb. 23).

Seven new sites

Seven sites have been identified in Jurong West, Bukit Panjang, Sembawang and Woodlands, according to the Singapore Food Agency (SFA) and HDB.

The sites will be used to farm vegetables and other food crops, and will also be used to pack and store produce.

They will be tendered out as a single site (in Jurong West) and three cluster sites (in Bukit Panjang, Sembawang and Woodlands).

Screenshot from SFA and HDB

Tenderers who successfully bid for cluster sites will be awarded all sites within the cluster, to allow them to cut costs through production at scale.

Single-site farms, on the other hand, provide opportunities to "testbed innovative ideas".

Tenderers must submit their proposals via GeBiz before the tender closes on Mar. 23, 4pm.

Proposals will be assessed on their bid price, production output, design and site layout, as well as their business and marketing plans.

More information can be found on SFA's website here.

Producing food locally

This is the second time tenders were launched for rooftop urban farms on carparks here — the first took place in Sep. 2020, with nine sites being awarded.

Collectively, the nine farming systems can potentially produce around 1,600 tonnes (1,600,000kg) of vegetables per year.

Having more space for commercial farming in land-constrained Singapore is one of SFA's strategies to achieve its "30 by 30" goal — which is to produce 30 percent of Singapore's food locally by 2030.

The move is also in line with HDB’s Green Towns Programme to intensify greening in HDB estates.

“Besides contributing to our food security, Multi-Storey Car Park (MSCP) rooftop farms help to bring the community closer to local produce, thereby raising awareness and support for local produce," said Melvin Chow, Senior Director of SFA’s Food Supply Resilience Division.

Jersey City Housing Authority To Host Vertical Farms

The partnership aims to provide more access to healthy food

Partnership Aims To Provide

More Access To Healthy Food

February 25, 2021

AeroFarms will construct and maintain 10 farming sites, the first of which will be built at the Curries Woods Community Resource Center as part of a new agreement between the city, AeroFarms, and the Jersey City Housing Authority.

Vertical farms will provide free nutritious food to residents in need now that the Jersey City Council has adopted a resolution approving an agreement between AeroFarms, the city, and the Housing Authority.

The new agreement means that vertical farms will be opened at Curries Woods and Marion Gardens.

The public housing farms, which will be funded by the city, will increase healthy food access where needed most and encourage residents to live healthier lifestyles.

The Jersey City Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), AeroFarms, and Jersey City Housing Authority will collaborate with the Boys & Girls Club and Head Start Early Childhood Learning programs to support produce distribution and healthy eating education.

“We’ve worked hard to keep the Vertical Farming Program a priority despite the impacts from this pandemic, which have disproportionately affected the more economically challenged areas and exacerbated societal issues such as healthy food access,” said Mayor Steven Fulop.

“We’re taking an innovative approach to a systemic issue that has plagued urban areas for far too long by taking matters into our own hands to provide thousands of pounds of locally-grown, nutritious foods that will help close the hunger gap and will have an immeasurable impact on the overall health of our community for years to come.”

City farming

AeroFarms will construct and maintain the farming sites. The first will be built at the Curries Woods Community Resource Center. The Boys & Girls Club and Head Start will integrate the vertical farm as a learning tool for youth within their educational programming.

Head Start, operated by Greater Bergen Community Action, plans to integrate greens into its early childhood meals.

AeroFarms indoor vertical farming technology uses up to 95 percent less water and no pesticides versus traditional field farming.

According to the city, the JCHA-Aerofarms Advisory Committee will be formed to provide strategic oversight and guidance throughout the program.

The steering committee will include Jersey City residents and stakeholders from the Boys & Girls Club and Head Start.

The city’s Vertical Farming Program will consist of eight additional vertical farms throughout Jersey City in senior centers, schools, public housing complexes, and municipal buildings.

The 10 sites will grow 19,000 pounds of vegetables annually using water mist and minimal electricity, according to the city.

The food is free to residents if they participate in five healthy eating workshops, and they will have the option of participating in a quarterly health screening.

“As a Certified B Corporation, we applaud Mayor Fulop’s leadership and advocacy to bring healthier food options closer to the community, and we are excited to launch together the nation’s first municipal vertical farming program that will have a far-lasting positive impact for multiple generations to come,” said Co-Founder and CEO of AeroFarms David Rosenberg.

The city’s Health and Human Service Department will run the program with a health-monitoring component to track participants’ progress under a greener diet, monitoring their blood pressure, cholesterol, diabetes, and obesity.

Crops will be integrated with other Healthy Food Access initiatives, including senior meal programs, according to the city.

“Access to healthy food and proper nutrition is directly linked to a person’s mental and physical health, and can decrease risks of chronic diseases while increasing life expectancy,” said Stacey Flanagan, director of Health and Human Service for Jersey City. “This past year has shed light on the health disparities that exist in urban areas nationwide, which is why we’ve remained focused on closing gaps where healthy food access is most needed, specifically for our low-income, youth, and senior populations.”

Healthy food initiatives

The Vertical Farming Program is part of the broader initiative from the World Economic Forum (WEF) toward partnerships with cities.

Jersey City is the first in the world to be selected by WEF to launch the Healthy City 2030 initiative, which aims to catalyze new ecosystems that will enable socially vibrant and health-centric cities and communities.

The vertical farming initiative is the latest and broadest effort Jersey City has launched around food access, including more than 5,000 food market tours for seniors to educate them on healthy eating, and the “Healthy Corner Store” initiative.

According to a 2018 city report, much of Jersey City could be described as a “food desert.”

The USDA defines a food desert as “a low-income census tract where either a substantial number or share of residents has low access to a supermarket or large grocery store.”

This means at least 500 people or 33 percent of the population live more than a mile from a supermarket or large grocery store.

According to the city, these deserts have led to an increased rate of diabetes, heart disease, obesity, and other diet-related illnesses in the more marginalized communities of Jersey City.

“We are thrilled that the vertical farms that will be installed at JCHA sites to enable some of our most vulnerable residents, including low-income households, children, and seniors, to have access to fresh, green produce that is nutritious, delicious, and easy to prepare,” said Vivian Brady-Phillips, director of the JCHA.

For updates on this and other stories check www.hudsonreporter.com and follow us on Twitter @hudson_reporter. Marilyn Baer can be reached at Marilynb@hudsonreporter.com.

These Buildings Combine Affordable Housing And Vertical Farming

Inside each building, the ground level will offer community access, while the greenhouse fills the second, third, and fourth floors, covering 70,000 square feet and growing around a million pounds of produce a year

A Million Pounds of Produce A Year, Along With Housing And Jobs.

[Image: Harriman/Gyde/courtesy Vertical Harvest]

02-18-21

Some vertical farms grow greens in old warehouses, former steel mills, or other sites set apart from the heart of cities. But a new series of projects will build multistory greenhouses directly inside affordable housing developments.

“Bringing the farm back to the city center can have a lot of benefits,” says Nona Yehia, CEO of Vertical Harvest, a company that will soon break ground on a new building in Westbrook, Maine, that combines a vertical farm with affordable housing. Similar developments will follow in Chicago and in Philadelphia, where a farm-plus-housing will be built in the Tioga District, an opportunity zone.

[Image: Harriman/Gyde/courtesy Vertical Harvest]

“I think what we’ve truly understood in the past year and a half—although we’ve been rooted in it all along—is that we have in this country converging economic, climate, and health crises that are rooted in people’s access to healthy food, resilient, nourishing jobs, and fair housing,” Yehia says. “And we saw this as an urban redevelopment tool that has the potential to address all three.”

Nona Yehia [Image: Harriman/Gyde/courtesy Vertical Harvest]

The company launched in 2015 on a vacant lot in Jackson, Wyoming, aiming in part to create jobs for people with physical and developmental disabilities in the area. In 2019, it got a contract from Fannie Mae to explore how its greenhouses could help with the challenge of food security and nutrition, studying how a farm could be integrated into an existing affordable housing development in Chicago as a model for new projects.

Now, as it moves forward with the Chicago project and expands to other cities, it will also create new jobs for people who might have otherwise had difficulty finding work, working with local stakeholders to identify underserved populations. “Part of this is providing healthy, nutritious food,” Yehia says, “but also jobs at livable wages. We’re positioning all of our firms to address the new minimum wage level of $15 an hour with a path towards career development.”

[Image: Harriman/Gyde/courtesy Vertical Harvest]

Inside each building, the ground level will offer community access, while the greenhouse fills the second, third, and fourth floors, covering 70,000 square feet and growing around a million pounds of produce a year. (The amount of housing varies by site; in Maine, the plan includes 50 unites of housing, and the project will also create 50 new jobs.) In Chicago, there may be a community kitchen on the first level. In each location, residents will be able to buy fresh produce on-site; Vertical Harvest also plans to let others in the neighborhood buy greens directly from the farm. While it will sell to supermarkets, restaurants, hospitals, and other large customers, it also plans to subsidize 10-15% of its harvest for local food pantries and other community organizations. “By creating a large-scale farm in a food desert we are creating a large source of healthy, locally grown food 365 days a year,” she says.

Correction: We’ve updated this article to note that the project in Maine has 50 units of housing, not 15, and the company received a contract—not a grant—from Fannie Mae.

ADELE PETERS

ADELE PETERS IS A STAFF WRITER AT FAST COMPANY WHO FOCUSES ON SOLUTIONS TO SOME OF THE WORLD'S LARGEST PROBLEMS, FROM CLIMATE CHANGE TO HOMELESSNESS. PREVIOUSLY, SHE WORKED WITH GOOD, BIOLITE, AND THE SUSTAINABLE PRODUCTS AND SOLUTIONS PROGRAM AT UC BERKELEY, AND CONTRIBUTED TO THE SECOND EDITION OF THE BESTSELLING BOOK "WORLDCHANGING: A USER'S GUIDE FOR THE 21ST CENTURY."

CANADA - CALGARY: Local Produce Options Expand With Vertically Farmed Greens

The newest local player is Allpa Vertical Farms. The company is headed by three young entrepreneurs who used their shared interest in food, sustainability, and engineering to build a vertical farming operation

Elizabeth Chorney-Booth

Feb 20, 2021

Pictured is a package of sunflower microgreens produced by ALLPA in Calgary on Thursday, February 11, 2021. Azin Ghaffari/Postmedia PHOTO BY AZIN GHAFFARI /Azin Ghaffari/Postmedia

Over the years, the local food movement has grown from a handful of agriculture advocates touting the importance of supporting local farmers to a large-scale demand for everything from meat to chocolate that’s been produced and, when possible, grown here in Alberta. With Canada’s Agriculture Day being this Tuesday, it’s as good a time as any to celebrate homegrown products, be it artisanal honey or good ol’ Alberta beef.

Yet, as we look outside at our February weather, it’s obvious that some of our favourite foods simply can’t grow in abundance here. Greenhouse technology allows farmers to grow local cucumbers and tomatoes alongside wheat and canola fields, but greenhouses take up a lot of real estate. A new breed of urban farmer is using vertical farming techniques to grow crops like microgreens and baby kale on a much smaller footprint, right inside the city limits.

Pictured are some of the microgreens produced by Allpa in Calgary. Azin Ghaffari/Postmedia PHOTO BY AZIN GHAFFARI /Azin Ghaffari/Postmedia

The newest local player is Allpa Vertical Farms. The company is headed by three young entrepreneurs who used their shared interest in food, sustainability, and engineering to build a vertical farming operation. It involves vertically stacked levels of plants, grown indoors, usually in a warehouse or shipping container. The lighting, irrigation, and soil are carefully controlled so that crop yields aren’t reliant on exterior factors like weather and sunlight.

Allpa specializes in microgreens, growing radish, broccoli, sunflower, and arugula sprouts that can be bought by the tub at the Italian Centre Shop and all Sunterra locations. Since microgreens only take about 11 days to go from seed to harvest, the Allpa crew can grow their greens to order, making for less food waste.

From left: Andrey Salazar and Guillermo Borges, Allpa co-founders, with Zakk Tambasco, head of production, with their products. Azin Ghaffari/Postmedia PHOTO BY AZIN GHAFFARI /Azin Ghaffari/Postmedia

“The company (began) with an internal conflict I had between climate change and farming,” says founder Andrey Salazar, who grew up on a coffee farm in Columbia and has studied physics and electrical engineering in Calgary. “I wanted to combine my background as a farmer and my practical skills as an engineer, so I went to my garage and started building the equipment.”

Allpa is far from the first vertical farming outfit in Calgary. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Deepwater Farms had developed a huge following among restaurant chefs with its greens grown via a vertical hydroponics system. The company was originally conceived as a closed-loop aquaponics operation, raising fish and using the fish waste to fertilize plants. Food safety regulations have prompted the company to decouple the two systems, but it continues to sell both indoor-grown baby kale, arugula and beet greens as well as barramundi and tilapia.

It’s been a successful model. Before COVID-19, the majority of Deepwater’s business was with restaurants seeking products previously unavailable from local producers (you don’t see a lot of barramundi swimming around Calgary), all of which came to a screeching halt last spring. The company was able to pivot and is now doing a booming retail business, with their products available in 80 retailers, including all Calgary Co-Op stores, select Safeway and Sobeys locations, Blush Lane and Community Natural Foods, among many others.

“We work with some of the best restaurants in the area and that’s how we started,” says Paul Shumlich, Deepwater’s founder and CEO. “Now we’re 99 percent selling to retail, which we’re very grateful for.”

Reid Henuset and Paul Shumlich of Deepwater Farms pose for a photo in the city’s first commercial aquaponics farm on Tuesday, November 20, 2018. Al Charest/Postmedia Al Charest/Postmedia

Vertical farming methods are hardly dominating in Alberta – with so much farmland we obviously have other options to grow food, along with a reliable flow of food grown in warmer climes. But it is taking hold in other parts of the world and Calgary has the potential to be a leader in vertical farming technology. The Harvest Hub is a local tech start-up developing soil-based indoor farms, with a focus on green energy and diversification of crops, which will allow urban farmers to go beyond microgreens and leafy greens. Founder Alina Martin says Harvest Hub has had success growing crops like saffron, zucchini, carrots, and bell peppers in its Calgary test farm. Once they hit the market, technological innovations should make vertical farming more feasible for urban growers.

“Vertical farming is one of the fastest-growing industries in the world, but most people in Canada don’t understand it,” Martin says. “As much as we romanticize the idea of having your food growing just down the street, the challenge here is the cost. You can’t be in downtown Calgary growing basil and make money. The infrastructure costs will kill you.”

While Martin suspects that Harvest Hub’s business will largely come from outside of Calgary (the company is working on addressing food insecurity in communities in Canada’s North), she does believe vertical farming is the way of the future on a global scale. While we may not have locally grown saffron in our cupboards in the immediate future, it is nice to have access to that Calgary-bred barramundi and handfuls of affordable microgreens for now.

Elizabeth Chorney-Booth can be reached at elizabooth@gmail.com. Follow her on Twitter at @elizaboothy or Instagram at @elizabooth.

Living Greens Farms Ramps Up Midwest Expansion

Living Greens Farm has upped its retail distribution with the addition of UNFI Produce Prescott, a division of United Natural Foods, Inc (UNFI)

Feb. 18th, 2021

by Melissa De Leon Chavez

FARIBAULT, MN - Living Greens Farm (LGF) has upped its retail distribution with the addition of UNFI Produce Prescott, a division of United Natural Foods, Inc. (UNFI). This new retail partnership will help LGF expand its product reach to independent, specialty, and co-op retailers throughout the upper Midwest.

According to a press release, LGF’s proprietary vertical indoor farming method yields high-quality, fresh produce. No pesticides or chemicals are used during the growing process. Throughout the growing, cleaning, and bagging process, LGF reduces handling and time to the retail shelf. All of these benefits continue to attract new users and new retail distribution.

Living Greens Farm has upped its retail distribution with the addition of UNFI Produce Prescott, a division of United Natural Foods, Inc (UNFI)

Beginning this month, LGF’s full line of products featuring ready-to-eat bagged salad products, such as Caesar Salad Kit, Southwest Salad Kit, Harvest Salad Kit, Chopped Romaine, and Chopped Butter Lettuce will be carried by UNFI Produce Prescott (formerly Alberts Fresh Produce).

Across the nation, UNFI has eight warehouses, and LGF’s products will be carried by its upper Midwest location, located just across the river from the Twin Cities in Prescott, Wisconsin.

As indoor farming becomes more popular, who will Living Greens Farm partner with next?

Stay tuned to AndNowUKnow as we cover the latest.

COMPANIES IN THIS STORY

We believe in revolutionizing how produce is grown throughout the world. Our products are fresh, local, and pesticide-free....

UNFI

UNFI is the leading independent national distributor of natural, organic and specialty foods and related products...

Seattle Architect Is Helping The Fast-Growing Field of Indoor Ag Take Root

Seattle architect Melanie Corey-Ferrini is launching a controlled-environment business with assists from Sabey Corp., and Microsoft. The multifaceted, to-be-named enterprise includes a training program at Alan T. Sugiyama High School at South Lake in Seattle, where she is pictured in the cafeteria with a grow tower. Anthony Bolante | PSBJ

By Marc Stiles – Senior Staff Writer, Puget Sound Business Journal

January 16, 2021

Seattle architect Melanie Corey-Ferrini’s kiosk-style lobby pop-up concept called G2 is the ultimate in farm-to-fork dining. Protein-rich grains and greens are grown on-site in the unmanned, transparent kiosk and combined with other veggies, roots, spices and dairy to make custom bowls ordered on a mobile app. G2 last summer was named best pioneering food service concept in a national contest.

It’s one small example of the possibilities of controlled-environment agriculture (CEA), which is at the heart of Corey-Ferrini’s latest endeavor: a multifaceted, urban ag project largely centered in Tukwila, where Sabey Corp. is providing warehouse space for hydroponic growing equipment that Microsoft donated.

Corey-Ferrini will use space at Sabey’s Intergate East data center campus to build and launch CEA education and business development programs this year.

CEA is a technology-based approach to food production that allows indoor farmers to maximize use of water, energy and labor. Worldwide in the third quarter, venture capitalists invested $1.6 billion in ag tech companies, bringing the 2020 total to $4.2 billion, according to PitchBook. Alexandria Real Estate Equities, a developer of life science office and lab space, offers early-stage companies move-in-ready space at its Center for AgTech in Durham, North Carolina.

The sector has struggled to put down roots in the Seattle region, where there has been one unsuccessful attempt. Now comes not only Corey-Ferrini’s to-be-named enterprise but also Kalera, a Florida-based company that plans to open a facility in 70,000 square feet of leased space in Lacey this year.

Several years ago, Corey-Ferrini consulted with Microsoft on a CEA project in Redmond. Contract farmers used Microsoft’s PowerBI and Azure platforms to grow in hydroponic towers lettuce and micro-greens for company cafeterias.

“I was like, why aren’t more people doing this? It seems like it should be a programmatic feature in all food-related spaces,” said Corey-Ferrini. “I’ve learned it’s really a little bit of robotics, a little bit of AI, a little bit of automation.”

As a member of Soroptimist Seattle, which works to empower women and girls, she is establishing a program at Alan T. Sugiyama at South Lake, an alternative public high school in the Rainier Valley. She is working with other groups like New Roots, an International Rescue Committee program that provides land and other support in South King County to around 150 immigrant and refugee families.

Deepa Iyer, senior program coordinator for New Roots, said a pilot indoor ag tech and business class will be offered at the Sabey building through Corey-Ferrini’s enterprise. She said it will provide pathways not only to a year-round growing platform but training for tech careers.

The experience of a Seattle indoor ag business, UrbanHarvest, shows the challenges of such an endeavor. Six years ago, it worked with Seattle’s Millionair Club Charity (now Uplift Northwest) during its launch, but the program shut down after about a year when it couldn’t raise additional funds, said founder Chris Bajuk.

Corey-Ferrini is approaching it with a long-term view and plans to build a multipronged enterprise with multiple income streams. Kara Anderson, director of architecture at Sabey, said Corey-Ferrini has a good shot at pulling this off.

“She’s got endless energy,” said Anderson, who added that, like Sabey, Corey-Ferrini is known for outside-the-box thinking.

“She’s not afraid to pick up an idea without knowing really how she’s going to pull it together. She just starts marching down the path to get partners and grab people into her extensive network to brainstorm,” said Anderson.

Sabey, a developer and operator of data centers nationwide, sees opportunities in the project for both its business and community.

“We’re interested in what’s going on in our backyard and opportunities to help out and make some lives better if we can,” Anderson said “At some point these indoor facilities will be monitored by computers and that, in turn, ends up feeding into the data center world.”

Melanie Corey-Ferrini

Position: Chief experience architect

Company: Dynamik Space, a design and branding company

Founded: 2000

Career: Also currently CEO of 3.14DC, which programs food and retail spaces

Lessons Learned

Use your sense of humor.

Be curious.

Don’t fear failure.

From A Landfill Site To An Urban Farm: The Transition That Kept A Thai City Fed During COVID-19

Many residents of Chiang Mai, where the farm is based, lost their tourist-dependent jobs during the start of the pandemic

15 Jan 2021

Rina Chandran Correspondent, Reuters

An urban farm in Thailand, built on a former landfill site, has been helping feed nearby residents during the COVID-19 crisis.

Many residents of Chiang Mai, where the farm is based, lost their tourist-dependent jobs during the start of the pandemic.

It could provide model of how to turn unused spaces into places that benefit the whole community.

Urban farming is an important tool in promoting sustainability and tackling food insecurity.

An urban farm developed on a former landfill site in northern Thailand boosted the food security and livelihoods of poor families during the coronavirus pandemic, and can be a model for unused spaces in other cities, urban experts said on Thursday.

The farm in Chiang Mai, about 700 km (435 miles) from the capital Bangkok, took shape during a nationwide lockdown to curb the spread of the coronavirus last year, when many of the city's residents lost their tourism-dependent jobs.

Supawut Boonmahathanakorn, a community architect who works on housing solutions for Chiang Mai's homeless and informal settlers, approached authorities with a plan to convert the unused landfill into an urban farm to support the poor.

"We had previously mapped the city's unused spaces with an idea to plant trees to mitigate air pollution. The landfill, which had been used for 20 years, was one of those spaces," he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

"Poor families spend more than half their earnings on food, so when their incomes dried up, they were struggling to feed their families. This farm has been a lifeline for some of them," he said, pointing to neat rows of corn and morning glory.

Coronavirus lockdowns worldwide have pushed more city dwellers to grow fruit and vegetables in the backyards and terraces of their homes, and forced authorities to consider urban farming as a means to boost food security.

In Chiang Mai, after authorities approved the farm plan, an appeal on social media resulted in donations of plants, seedlings and manure from residents, Supawut said.

With diggers loaned by the city, Supawut and his team cleared some 5,700 tonnes of rubbish on the 4,800 square-metre (0.48 hectare) plot that lies next to a canal and a cemetery.

The land was levelled, and a rich topsoil added to offset the degraded soil. The farm opened to the community in June.

About half a dozen homeless families, students from a public school and members of the public grow eggplant, corn, bananas, cassava, chilli, tomatoes, kale and herbs, Supawut said.

"In cities, we have lost our connection with food production, but it is a vital skill," he said.

"Urban farms cannot feed an entire city, but they can improve nutrition and build greater self-sufficiency especially among vulnerable people. They are important during a pandemic - and even otherwise," he added.

Supawut Boonmahathanakorn stands by the urban farm he helped create.

Image: Thomson Reuters Foundation/Rina Chandran

Come together

Urban agriculture can potentially produce as much as 180 million tonnes of food a year - or about 10% of the global output of pulses and vegetables, according to a 2018 study led by Arizona State University.

Rooftop farms, vertical gardens and allotments also help increase vegetation cover, which is key to limiting rising temperatures and lowering the risk of flooding in cities.

While land in cities is scarce and expensive, rooftops and spaces below expressways and viaducts can be repurposed, said landscape architect Kotchakorn Voraakhom, who designed Asia's largest urban rooftop farm in Bangkok.

"We need imagination and greater flexibility in our laws to turn such spaces into urban farms," she said.

"The Chiang Mai farm is a sandbox - it shows it can be done in even the most unlikely of spaces if the government and the community come together," she added.

For Ammi, a homeless indigenous Akha woman who has lived at the farm since July, the corn, melons and cabbage that she grows have fed her and her husband, and provided a small income.

"It gives people like me an opportunity to be self-sufficient," she said. "We need more such farms in the city."

Lead photo: The farm provides a model of how to turn unused spaces into places that benefit the whole community. REUTERS

This article is published in collaboration with Thomson Reuters Foundation trust.org

Greenhouse Villages To Sprout In Metro Manila

The Agricultural Training Institute (ATI) recently partnered with four barangays in Caloocan and Quezon for the creation of greenhouse villages as part of the urban agriculture program of the government

Louise Maureen Simeon

12/22/2020

MANILA, Philippines — The Department of Agriculture will start establishing greenhouse villages in Metro Manila to help ensure a sustainable food supply in the country.

The Agricultural Training Institute (ATI) recently partnered with four barangays in Caloocan and Quezon for the creation of greenhouse villages as part of the urban agriculture program of the government.

Urban agriculture is one of the flagship programs of the Plant Plant Plant initiative of the DA to boost supply amid the pandemic.

Barangays 179 and 180 in Caloocan and barangays Payatas and Tandang Sora in Quezon City will serve as pilot areas for the project.

Under the partnership, ATI will provide funding assistance for the establishment of a greenhouse village per barangay.

This will feature one unit of high greenhouse with an administration office and storage area, one unit of seedling nursery with micro-sprinkler irrigation, and one unit of production area with drip kit irrigation system.

The agreement also calls for 10 sessions of training program from the construction phase until harvest time.

Through this, the DA and ATI aim to showcase doable technologies of protective farming systems.

The partnership also targets to increase the production of vegetables and to make these available in the barangay level throughout the year amid varying weather conditions.

DA’s urban agriculture program has been gaining positive feedback from more institutions as it continues to help stabilize food supply, foster social integration, and protect the environment through eco-friendly methods and innovative gardening methods.

It was launched in April as an immediate response to the food supply disruption due to the pandemic.

Agrifood Tech Firms Are Flocking To Singapore, With Perfect Day The Latest To Land

US alt-dairy startup Perfect Day revealed today that it will set up an R&D facility in Singapore, with the city-state’s minister for trade and industry predicting “many other companies” will be joining it to take advantage of the growing agrifood tech ecosystem there

December 20, 2020

US alt-dairy startup Perfect Day revealed today that it will set up an R&D facility in Singapore, with the city-state’s minister for trade and industry predicting “many other companies” will be joining it to take advantage of the growing agrifood tech ecosystem there.

A*STAR's headquarters in Singapore. Image credit: A*STAR

California-based Perfect Day is establishing the joint R&D center in collaboration with Singapore’s Agency for Science, Technology, and Research (A*STAR.)

This center will bring together A*STAR’s expertise in areas such as taste analytics, cell biology, and protein biotech. The aim of the collaboration is to “build analytical platforms to characterize and quantify the key components in dairy food products that provide their distinctive taste and feel,” the startup said in a statement.

Founded in 2014, Perfect Day produces ‘animal-free’ dairy products using microflora to ferment sugars to create the same proteins, casein, and whey present in animal milk.

The startup is just the latest international agrifood tech company to set up shop in Singapore.

Invest with Impact. Click here.

Last month, German indoor farming firm &ever said it would establish its global R&D center in the city-state to carry out research into energy efficiency and yield optimization for indoor vertical farms. It’s also constructing a “mega-farm” in the east of Singapore with an annual production capacity of over 500 tons that is set to open by the end of 2021.

In October, US alt-protein startup Eat Just announced it would invest a total of $100 million with investor Proterra to build Asia’s first plant-based protein factory in Singapore. Earlier this month, the city-state handed Eat Just the world’s first regulatory approval for a cell-based, cultured meat product, clearing its ‘lab-grown’ chicken bites for sale to the public.

Swiss food industry majors Buhler and Givaudan announced the launch of a joint innovation center in Singapore in February to explore textures and tastes for plant-based protein products. French animal feed firm Adisseo set up an aquaculture R&D center in Singapore back in December 2019 to research aquatic animal health and nutrition.

Citing data from AgFunder, Singapore Minister of Trade & Industry Chan Chun Sing said that the global agrifood sector is “primed for growth” with investment into agrifoodtech startups growing 47% year-on-year in 2018 and a further 17% in 2019 to reach $19.8 billion. [Disclosure: AgFunder is AFN‘s parent company.]

With its “unique farm-to-fork ecosystem and track record for technical capabilities, quality branding, and intellectual property [IP] protection, Singapore aims to capture a significant share of the wave of economic opportunities in agrifoodtech,” Chan told reporters at a press conference announcing Perfect Day’s partnership with A*STAR.

Alt-protein products like those being developed by Perfect Day, Just Eat, and local players including Shiok Meats and TurtleTree Labs — which announced its $6.2 million pre-Series A round last week — have a critical role to play in feeding countries and cities like Singapore, where arable land is minimal and primary food sources are typically located far away.

“Alternative proteins will add to the suite of options we have without being restrained by factors like the [amount] of land and other natural resources we have. Overall, [they provide] a much more efficient, sustainable way to feed the population, across Asia, where demand will go up proportionally with the growth of the middle class,” Chan said.

But the buck doesn’t need to stop at Singapore securing its own nutritional needs, he added.

“We are not limiting our aspirations just to the domestic market. The larger market for this sector is really [the] growing needs for the Asia-Pacific, that we hope to capture. Look at China, Indonesia, India – as people become more affluent, as they seek higher quality food products, there will be a bigger market for these kinds of products. How do we feed a growing population in a sustainable manner that is also good for the environment? So our sense is not just how big the local market is, but how big the global market can be.”

“We want to make sure the core IP, the core R&D happens here – so the high-value part of the value chain is housed in Singapore, and we can attract the investment and the people to come here,” Chan said.

He noted that in addition to the arrival of foreign startups and corporates, as well as the growth of local players, a variety of domestic and international investors are contributing to the development of Singapore’s agrifood tech ecosystem.

“We are also building a vibrant cluster of financing firms across various stages, for example, New Protein Capital, EDBI, Temasek, and Proterra, as well as a base of global agrifood accelerators [such as] Big Idea Ventures‘ alternative proteins accelerator and GROW Accelerator […] Our eventual aim is to build up the talent pool with the expertise to deploy more than S$90 million [$67.5 million] of capital.” [Disclosure: GROW Accelerator is operated by AgFunder, AFN‘s parent company.]

Returning to Perfect Day’s R&D center announcement, Chan said it is another “milestone in our ongoing journey.”

“There will be many other companies joining us to build up our ecosystem,” he continued. “We’re optimistic this can become a new pillar of our economic development, providing us with greater [economic] diversity, food security for Singapore, and new opportunities in countries beyond Singapore.”

Singapore sovereign fund Temasek led Perfect Day’s $140 million Series C round in December 2019.

Got a news tip? Email me at jack@agfunder.com or find me on Twitter at @jacknwellis

alt dairy, asia, Europe, Germany, indoor agriculture, indoor farming, singapore, United States, urban agriculture, urban farming, vertical farming

AUSTRALIA: Can Urban Areas Become A Powerhouse For Horticultural Production?

Hort Innovation, a grower-owned research corporation, is working with a consortium led by agricultural consultancy RMCG in partnership with the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and urban agriculture consultancy Agritecture to assess the potential of emerging production technology and its application in urban Australia

DECEMBER 18, 2020

Australia is looking to become more engaged with the global swing to high-technology horticulture in urban areas.

High-tech urban hort is being implemented across the world using vertical farm systems, hydroponics and aquaponic systems and nearly fully automated production as well as rooftop, underground and floating farms.

Hort Innovation, a grower-owned research corporation, is working with a consortium led by agricultural consultancy RMCG in partnership with the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and urban agriculture consultancy Agritecture to assess the potential of emerging production technology and its application in urban Australia.

They are looking at the potential benefits for growers and Australia through the wider use of technology such as vertical farm systems and hydroponics in food production and delivery systems.

Hort Innovation CEO Matt Brand said bringing such technology to Australia would attract capital and new entrants to the sector with new ideas, approaches and mindsets.

NO URBAN MYTH: CEO of Hort Innovation Matt Brand said the research and development corporation was keen to explore the potential for increased horticultural production in urban areas.

"It gives us the opportunity to grow more from less and to keep demonstrating the good work that Australian growers do, day in day out, providing food to families both here and overseas.

"Urban in this context also captures regional areas and hubs. Growers will use the technology as part of the overall production mix. It's another production system that will be part of the diversity and variety that is Aussie horticulture," he said.

"High technology horticulture may have the potential to play a significant role in increasing Australia's horticulture sector value and help achieve Australia's target of a $100 billion industry by 2030."

The feasibility study aims to identify the opportunities and challenges for high technology horticulture in urban Australia.

The outcomes of the study will identify future priorities for research, development and extension activities and investment into Australian high technology horticulture in urban areas.

The study is being guided by an industry-led reference group including growers and emerging commercial leaders engaged in urban high technology horticulture in Brisbane and Sydney, members of local city councils, and subject-matter experts in protected cropping.

Greenhouse and hydroponic consultant Graeme Smith said these new systems were the modern face of horticulture that should complement the current supply chain in a key range of nutritious and delicious produce.

Lead photo: PERFECTLY RED: Hydroponics has enabled the intensive production of premium quality tomatoes and other horticultural staples in protected environments.

This story Can urban areas become a powerhouse for horticultural production? first appeared on Farm Online.

Making Singapore A Land of Farmers

By 2030, the government has announced that 30 percent of food consumed locally will be locally grown under its “30 by 30” initiative

AUTHOR Malay Mail

December 13, 2020

Kuala Lumpur, Dec. 13 — Singapore is known for its ambition.

This tiny nation (just 700 square kilometers in area, 400 times smaller than Malaysia) is now one of the most competitive economies on Earth.

And yet even by its own standards, it has set a very lofty goal.

By 2030, the government has announced that 30 percent of food consumed locally will be locally grown under its “30 by 30” initiative.

Presently, under 10 percent of the things Singaporeans eat are grown in Singapore. This is extremely low by global standards but again Singapore has a resident population of almost six million, on a small island, with just 400 acres of true farmland in the entire country.

Four hundred acres is the size of a single modest farm in places like the USA and even a mid-scale Malaysian plantation can be double the size.

Yet in Singapore, this is the sum total of all our agricultural land so how on earth are we going to feed millions of people?

The answer is an unprecedented deployment of technology. Vertical farms, advanced hydroponics and growing techniques using nutrients, perfectly calibrated irrigation systems, robotics, and 24/7 monitoring.

The government is also going to work to utilize urban spaces – rooftops, balconies, alleys – on quite an unprecedented scale to achieve greater food self-sufficiency.

While the investment will be high, Covid-19 has proved the benefits are likely to be worth it.

The pandemic showed us that global supply chains can collapse and in times of disruption, governments will prioritize feeding their own populations.

A country with no farmland and agriculture is completely at the mercy of its suppliers.

While Singapore has long been somewhat cognizant of this vulnerability – the government does hold strategic food reserves – this simply isn’t enough and some sort of local agricultural base is needed.

Of course, local sourcing doesn’t just improve our security, it also reduces our carbon footprint and can help ensure what is being consumed is of a very high standard.

So more local farming seems like a clear win all around.

But things are never quite so simple.

As we ramp up our urban farming capacity, won’t we once again be shifting more power and capital to the same tech companies and multinationals that already control so much of our lives?

Recently the government announced that well-known agri-tech company Bayer would launch a large-scale vertical farm in Singapore with a multimillion-dollar investment.

Surely it’s only a matter of time before we have Amazon and Tencent farms. They already supply our homes with all manner of goods, so why not farmed produce? Basically, are we about to see another great leap forward in the dominance of big tech?