Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Lettuce: Meet The Salad Kings of SA

Back home in East London in 1978, he made the decision to become a farmer, an option that was met with criticism from family and peers who did not have farming backgrounds.

By Glenneis Kriel

August 6, 2021

Not knowing what to do after finishing his military service back in the 1970s, Michael Kaplan set off to work on a kibbutz in Israel, where he was exposed to banana, dairy and chicken production.

From there, he backpacked through Europe, and was particularly impressed by the new technologies that farmers in the Netherlands were using to protect their crops and improve production efficiencies.

Back home in East London in 1978, he made the decision to become a farmer, an option that was met with criticism from family and peers who did not have farming backgrounds.

“My mother, Ethel, was a doctor and my father, Lewis, a lawyer, so they thought I was completely bonkers when I told them I wanted to farm,” recalls Kaplan.

In pursuit of his dream, he wanted to study agriculture at the Elsenburg Agricultural

Training Institute in the Western Cape, but entries had already closed by the time he applied. So he began working at what was then the English Trust Company farm in Stellenbosch, thanks to an introduction from his childhood friend, Bruce Glazer, who already worked there.

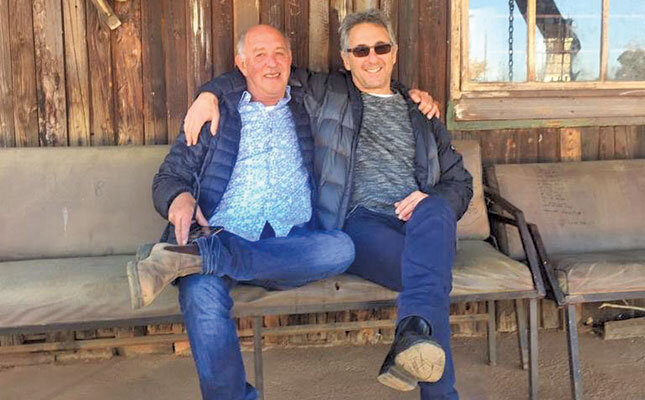

Dew Crisp was co-founded by childhood friends Michael Kaplan (left) and Bruce Glazer.

“It really was a case of being in the right place at the right time, as the English Trust Company was one of the first to introduce farming tunnels in South Africa.

“They produced tomatoes using the nutrient film technique [NFT] and experimented with the gravel flow technique [GFT] to grow butter lettuce and celery,” says Kaplan.

These hydroponic techniques, he explains, are similar in that both entail the circulation of a nutrient solution in a closed system. The difference is that with GFT, gravel is used as a growth medium, whereas, with NFT, plants are suspended and their roots exposed.

Early days

Kaplan worked at the English Trust Company for two years. He then learnt that the Joburg Market sold up to three times more vegetables than its Cape Town equivalent.

Deciding it was time to spread his wings, he drove up to Johannesburg, where he began looking for a business partner and land on which to grow his own produce.

“My mother lent me R10 000, which I used to rent land near Heidelberg [about 50km south-east of Johannesburg] and produce celery under 2 000m² of nets using GFT,” says Kaplan.

In 1981, Heidelberg was hit by a severe snowstorm. It destroyed almost all of Kaplan’s infrastructure, but he managed to save most of the crop and used the income from the sale to rebuild his operation.

“I kept costs low by doing almost everything myself, and using the income to grow the operation, reaching 8 000m² by the third year of production,” recalls Kaplan.

In his fourth year of operation, he started looking for land closer to the Joburg Market and with more favourable production conditions.

“These are actually two of the most important prerequisites for farming success; you need to be close to the market, and farm in a region where the climatic and production conditions are suited to the crop you want to grow. I learnt the hard way that the Highveld is unsuited to salad production in winter,” he says.

Financing

With a clearer idea of what he required, Kaplan bought land near Nooitgedacht and applied to the Land Bank for a loan.

Being unfamiliar with hydroponic production, the bank declined his application, but Kaplan managed to secure a loan from First National Bank at an interest rate of 26%. Fortunately, the market was far less competitive and demanding in those days, which enabled him to repay the loan quickly.

“It would be almost impossible to accomplish the same today; land, labour, infrastructure and production costs are exorbitant. And you buy everything in dollars and euros but get paid in rands,” he says.

Costs are driven up even further by international production standards and auditing programmes such as GlobalGAP and HACCP, which are required to supply most markets today, while market access is complicated by retailers and big buyers demanding huge supply volumes all year round.

An impressive growth path

In the intervening years, Glazer had studied agriculture at Elsenburg and thereafter also worked on a kibbutz in Israel. On his return in 1984 he bought a farm near Kaplan’s, and two years later the two decided to amalgamate their businesses to create better economies of scale.

The new company was called Dew Crisp. To add value to their produce, they sold ready-to-eat lettuce in pillow packs, a market they dominated for over six years.

Since then, Dew Crisp has grown into one of the largest value-added salad suppliers in South Africa, expanding their geographical footprint over time to lengthen their production season and mitigate climate and production risks.

Today, they have 10ha under production in Muldersdrift, 200ha near Bapsfontein and 140ha near Philippi, as well as processing plants in the West and East Rand of Gauteng and in Franschhoek in the Western Cape.

Dew Crisp also sources produce from between 15 and 20 selected farmers across geographically diverse regions, some of whom have been supplying the business for over 25 years.

The company’s empowerment arm, Rural Farms, supports and sources produce from five previously disadvantaged smallholder farmers.

In 2009, Agri-Vie, the Africa Food & Agribusiness Investment Fund, bought a 49% share in Dew Crisp, which enabled Kaplan and Glazer to grow the business and place greater emphasis on financial administration and corporate governance.

“We realised that it wasn’t enough to simply follow the market; we had to create our own destiny by becoming market leaders.

“To achieve this, we needed to be innovative and have a really good understanding of consumer trends. We’ve introduced many firsts on the market,” says Kaplan.

Glazer and Kaplan have also drastically diversified their market risks by supplying all the major retailers, various prepared-meal manufacturers such as the Rhodes Food Group, and food service companies such as KFC, McDonald’s, Nando’s and Burger King.

Production

Dew Crisp’s produce is grown under nets, in plastic tunnels and in open fields.

“Tomatoes, English cucumbers and peppers don’t like water or cold [air] on their leaves, so we generally produce them under plastic,” says Kaplan.

Shade nets are used in the production of salad vegetables, as these are sensitive to sunlight, heat and wind. The nets also protect against hail and bird damage while reducing the impact of rain by breaking up the droplets. In addition, they help to absorb heat and keep the production area cool.

Open-field production is highly seasonal and limited to hardier vegetables such as sweetcorn, onions and cabbage.

Most of the produce is grown in hydroponic systems, where the plants are supplied with nutrients via a nutrient solution. In most cases, Dew Crisp uses closed hydroponics (recycled water).

“Closed hydroponics is used for salad production in GFT, whereas open hydroponics is used in the production of tomatoes and cucumbers, as they are really sensitive to diseases that might spread with the water. For this reason, each of these plants has access to its own dripper,” explains Kaplan.

Sawdust and coco peat are used as growth mediums in the open hydroponic systems.

“Some farmers sterilise these mediums to reuse them, but I prefer using them only once to prevent disease outbreaks. We do, however, reuse the gravel in the open gravel system, after cleaning it with a chlorine solution at the end of each production cycle.”

In the same way, the crops that are planted in the soil are rotated to prevent a build-up of diseases.

Water quality largely determines the success of a hydroponic system, so a farmer should not even think of using it if the irrigation water is of poor quality or has high levels of chlorine or sodium. Water can be pretreated to rectify mineral imbalances, but this drives up costs. Water should, in any case, be filtered before use.

Dew Crisp has worked with scientists for years to refine its plant feeding programmes based on the nutritional requirements of various crops during different development phases.

“The trick is to supply exactly what the plant needs. An undersupply leads to plant deficiencies, while an oversupply is wasteful and might result in damage to the system and plants. To prevent this, we constantly monitor the recycled solution, plant growth and climatic conditions, and tweak the nutritional programme accordingly,” says Kaplan.

Achieving this with open-field crops is even more challenging due to soil differences. Soil, nonetheless, has a higher buffering capacity and is thus more forgiving.

The farm does not employ any climate-control technology because of its high capital and running costs. Instead, tunnel windows are opened and closed to augment ventilation and reduce the interior temperature.

Even without climate-control technology, production is energy-intensive, as the water has to be recycled continuously. Back-up generators are a necessity, as most of the salads will die within hours if water flow is interrupted.

Advice

Farming, and especially farming under protection, has become highly specialised over the years, with low profit margins leaving little room for error.

“In the past, when a buyer ordered a hundred frilly lettuces, we could plant 150 and it didn’t really have an impact on the bottom line. These days, production costs are so high that we plant to order and programme,” says Kaplan.

The shift has also made it increasingly important for farmers to make use of consultants to fill their knowledge gaps.

“If you want to be successful today, you need to surround yourself with people who are better skilled than you are in their respective jobs.”

Email Michael Kaplan at mkaplan@dewcrisp.com.

Lead Photo: Shade nets are used in the production of salad vegetables, as these are sensitive to sunlight, heat and wind. Photo: Dew Crisp

Technology Is Shaping The Future of Food But Practices Rooted In Tradition Could Still Have A Role To Play

Its executive summary said the food we consume — and the way we produce it — was “doing terrible damage to our planet and to our health.”

By Anmar Frangoul

August 6, 2021

From oranges and lemons grown in Spain to fish caught in the wilds of the Atlantic, many are spoiled for choice when it comes to picking the ingredients that go on our plate.

Yet, as concerns about the environment and sustainability mount, discussions about how — and where — we grow our food have become increasingly pressing.

Last month, the debate made headlines in the U.K. when the second part of The National Food Strategy, an independent review commissioned by the U.K. government, was released.

The wide-ranging report was headed up by restaurateur and entrepreneur Henry Dimbleby and mainly focused on England’s food system. It came to some sobering conclusions.

Its executive summary said the food we consume — and the way we produce it — was “doing terrible damage to our planet and to our health.”

The publication said the global food system was “the single biggest contributor to biodiversity loss, deforestation, drought, freshwater pollution and the collapse of aquatic wildlife.” It was also, the report claimed, “the second-biggest contributor to climate change, after the energy industry.”

Dimbleby’s report is one example of how the alarm is being sounded when it comes to food systems, a term the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN says encompasses everything from production and processing to distribution, consumption and disposal.

According to the FAO, food systems consume 30% of the planet’s available energy. It adds that “modern food systems are heavily dependent on fossil fuels.”

All the above certainly provides food for thought. Below, CNBC’s Sustainable Future takes a look at some of the ideas and concepts that could change the way we think about agriculture.

Growing in cities

Around the world, a number of interesting ideas and techniques related to urban food production are beginning to gain traction and generate interest, albeit on a far smaller scale compared to more established methods.

Take hydroponics, which the Royal Horticultural Society describes as “the science of growing plants without using soil, by feeding them on mineral nutrient salts dissolved in water.”

In London, firms like Growing Underground are using LED technology and hydroponic systems to produce greens 33-meters below the surface. The company says its crops are grown throughout the year in a pesticide free, controlled environment using renewable energy.

With a focus on the “hyper-local”, Growing Underground claims its leaves “can be in your kitchen within 4 hours of being picked and packed.”

Another business attempting to make its mark in the sector is Crate to Plate, whose operations are centered around growing lettuces, herbs and leafy greens vertically. The process takes place in containers that are 40 feet long, 8 feet wide and 8.5 feet tall.

Like Growing Underground, Crate to Plate’s facilities are based in London and use hydroponics. A key idea behind the business is that, by growing vertically, space can be maximized and resource use minimized.

On the tech front, everything from humidity and temperature to water delivery and air flow is monitored and regulated. Speed is also crucial to the company’s business model.

“We aim to deliver everything that we harvest in under 24 hours,” Sebastien Sainsbury, the company’s CEO, told CNBC recently.

“The restaurants tend to get it within 12, the retailers get it within 18 and the home delivery is guaranteed within 24 hours,” he said, explaining that deliveries were made using electric vehicles. “All the energy that the farms consume is renewable.”

Grow your own

While there is a sense of excitement regarding the potential of tech-driven, soilless operations such as the ones above, there’s also an argument to be had for going back to basics.

In the U.K., where a large chunk of the population have been working from home due to the coronavirus pandemic, the popularity of allotments — pockets of land that are leased out and used to grow plants, fruits and vegetables — appears to have increased.

In September 2020 the Association for Public Service Excellence carried out an online survey of local authorities in the U.K. Among other things it asked respondents if, as a result of Covid-19, they had “experienced a noticeable increase in demand” for allotment plots. Nearly 90% said they had.

“This alone shows the public value and desire to reconnect with nature through the ownership of an allotment plot,” the APSE said. “It may also reflect the renewed interest in the public being more self-sustainable, using allotments to grow their own fruit and vegetables.”

In comments sent to CNBC via email, a spokesperson for the National Allotment Society said renting an allotment offered plot holders “the opportunity to take healthy exercise, relax, have contact with nature, and grow their own seasonal food.”

The NAS was of the belief that British allotments supported “public health, enhance social cohesion and could make a significant contribution to food security,” the spokesperson said.

A broad church

Nicole Kennard is a PhD researcher at the University of Sheffield’s Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures.

In a phone interview with CNBC, she noted how the term “urban agriculture” could refer to everything from allotments and home gardens to community gardens and urban farms.

“Obviously, not all food is going to be produced by urban agriculture, but it can play a big role in feeding local communities,” she said.

There were other positives, too, including flood and heat mitigation. “It’s … all those benefits that come with having green spaces in general but then there’s the added plus, [which] is that you’re producing food for local consumption.”

On urban farming specifically, Kennard said it provided “the opportunity to make a localized food system” that could be supported by consumers.

“You can support farms that you know, farmers that you know, that are also doing things that contribute to your community,” she said, acknowledging that these types of relationships could also be forged with other types of farms.

Looking ahead

Discussions about how and where we produce food are set to continue for a long time to come as businesses, governments and citizens try to find ways to create a sustainable system that meets the needs of everyone.

It’s perhaps no surprise then that some of the topics covered above are starting to generate interest among the investment community.

Speaking to CNBC’s “Squawk Box Europe” in June, Morgan Stanley’s global head of sustainability research, Jessica Alsford, highlighted this shift.

“There’s certainly an argument for looking beyond the most obvious … ways to play the green theme, as you say, further down the value and the supply chain,” she said.

“I would say as well though, you need to remember that sustainability covers a number of different topics,” Alsford said. “And we’ve been getting a lot of questions from investors that want to branch out beyond the pure green theme and look at connected topics like the future of food, for example, or biodiversity.”

For Crate to Plate’s Sainsbury, knowledge sharing and collaboration will most likely have a big role to play going forward. In his interview with CNBC, he emphasized the importance of “coexisting with existing farming traditions.”

“Oddly enough, we’ve had farmers come and visit the site because farmers are quite interested in installing this kind of technology … in their farm yards … because it can supplement their income.”

“We’re not here to compete with farmers, take business away from farmers. We want to supplement what farmers grow.”

Lead Photo: Fruit and vegetable allotments on the outskirts of Henley-on-Thames, England.

They Left The City To Start A Farm, And This New Wave of Farmers Is Urban-Raised, University-Educated And Committed To Environmental Practices

Many have chosen to leave the city to improve work-life balance, have more space or find more affordable housing. Choosing to leave the city to switch careers and become farmers? Yes, this is also happening.

By Cristina Petrucci

July 20, 2021

Many have chosen to leave the city to improve work-life balance, have more space or find more affordable housing. Choosing to leave the city to switch careers and become farmers? Yes, this is also happening.

Going from urbanite to full-fledged farmer is one giant leap of faith. A 2018 Statistics Canada report said that the proportion of younger people and women taking up farming has increased.

The profile of the typical Canadian farmer is changing. These new farmers are typically urban-raised, university-educated, and have a strong commitment to environmental and sustainable practices. And many do not have a family history or background in farming.

“I never had a green thumb,” said Aminah Haghighi. “I could barely keep houseplants alive.” Haghighi is the founder and head lettuce of Raining Gold Family Growers, established in January 2021 and based in Hillier, Prince Edward County. She is currently farming a quarter of an acre and has a direct-to-consumer sales approach. Starting in January, Haghighi had to be quick on her feet to determine what she could sell at that time.

“I came up with the idea of selling microgreens as that is something you can grow indoors under lights on shelves,” she said. Her efforts paid off. She had a total of 80 CSA (community-supported agriculture) subscribers and raised just under $10,000 in revenue. “That was the first time I felt connected with the community, because they wanted to see me succeed,” she says.

Ultimately, what led her to become a farmer is her keen ability to solve problems and to do it as quickly as possible.

Oh, and the pandemic also played a major role.

“A few weeks before the first lockdown in Ontario, my second daughter was born,” she explained. “Everything was slowly coming to a halt all over the world, and I didn’t really know what grocery stores would look like and we all thought the world was basically ending.” That’s when Haghighi decided to rip up the grass in her Toronto home and start growing in her small backyard garden.

Providing food security for her family during the whirlwind that was the first few months of the pandemic, and having something of her own, was why she started gardening. “As a mom who had no control over my body or control over my time, this was sort of a way to regain control in my life.”

Questions of food security and sustainability also crossed Judy Ning’s mind during the initial months of the pandemic. Along with her husband Hans and their two children, they left Montreal to pursue their dream of having a homestead.

“Our hospitality business took a major hit, and we made the decision to give that up, sell our house, and chase our dream 10 years ahead of time,” Ning writes.

Paper Kite Farm was born in February 2021 with their first seedlings and, in June, they started selling their garden veggies and ready-made meals and beverages at the Picton Farmers’ Market every Sunday.

Their farm is situated in North Marysburgh, Prince Edward County, and the Ning family are currently farming a quarter of an acre while also raising laying hens.

Ning had a rural upbringing and is ethnically Hmong, a hill tribe people. “We are found all over Southeast Asia and my parents were born in Laos,” said Ning. “Farming was and still is a huge part of the Hmong culture. While I didn’t always appreciate the garden in my youth, I’m now doing my best to tap back into my heritage.”

Her husband, Hans, is of Tawainese heritage and, as such, the Ning family are growing several Asian varietals in their row beds, such as bok choy, mizuna, napa cabbages and yard long beans. They are also growing berries and fruits in their food forest and permaculture beds.

The path to farming is not easy. The uncertainties and lack of control when dealing with crops have created pangs of self-doubt. “I want to quit everyday,” said Haghighi. “Ten times a day I’m like ‘Oh my God, what am I doing?’ but then 25 times a day I think this is totally what I’m supposed to be doing.”

On the operational front, issues like tackling insects without the use of pesticides, choosing the right soil for seedlings and managing the upfront costs of equipment are hard to ignore.

“In the early days getting financing was one of the biggest hurdles that we faced,” said Stephanie Laing. Laing and her partner, Heather Coffey, founded Fiddlehead Farm in 2012 and grow more than 50 types of vegetables year-round in their market garden of 10 acres in Demorestville, Prince Edward County.

Laing found that most lending institutions were used to farms that were “hundreds to thousands of acres” in size, not the smaller operations such as Fiddlehead.

Fortunately, Laing and Coffey could rely on the assistance of their families to co-sign the mortgage on their farm. They also relied on grants, which they’ve taken advantage of for some early infrastructure, such as their wash station, irrigation pond and some equipment.

It had always been a goal for Laing and Coffey to start a farm. With their respective environmental studies and landscape ecology background, as well as “WWOOF-ing” (Willing Workers on Organic Farms) for two years, they felt ready. They decided to settle in Prince Edward County to be midway between their families in Newmarket and Montreal.

“I think for our first six to eight years we didn’t take a single vacation; we just worked non-stop,” said Laing. She recalled how “overeager” they were initially, adding a flock of laying hens and a handful of pigs along with turkeys and ducks. Financially that was not viable, so they focused solely on their market garden and increasing their CSA membership.

Despite the hurdles in their early years, Laing is satisfied with where they are now. “I am happy with what I do for a living,” she said, “I would love it if it paid a bit better, but I really enjoy the work.”

With almost 10 years running their farm, Laing’s advice for new farmers, or those looking to become farmers, is to treat it as a business. “One of the reasons we have been successful is because we have always paid really close attention to our finances.” They’ve always “planned down to the penny,” ensuring that their farm is both survivable and sustainable.

They are now able to enjoy the fruits of their labour and set money aside to invest for things down the road, like getting the farm to be as off grid as possible.

She encourages new farmers to ask themselves what they want from the farm: to either work full- or part-time for it. “It’s a business and it’s also really involved with your life, and you need to think of those two things together,” she adds.

“I have a crazy amount of people that message me all the time saying that I’m living the dream and they wish they could do what I’m doing,” said Haghighi.

US (IA): Removing Seasonality by Rolling Out Multiple Farms Throughout The State

“We want Nebullam Farms to be available in every city throughout the US, so we can fulfill our mission of creating access to reliable and local food for everyone, year-round,” says Clayton Mooney, founder of Nebullam

By Rebekka Boekhout

July 6, 2021

“We want Nebullam Farms to be available in every city throughout the US, so we can fulfill our mission of creating access to reliable and local food for everyone, year-round,” says Clayton Mooney, founder of Nebullam.

Over half of the Nebullam team is comprised of Iowa State University Alumni. Today, Nebullam HQ and its Nebullam Farm 1 in Ames, located in the Iowa State University Research Park. At the end of this year, the company will be launching Nebullam Farm 2, which will be in another location in Iowa.

Clayton Mooney, founder

Tomatoes as a cash cow

The company’s staple food is Red Butterhead Lettuce. Next to that, Nebullam grows Red Oakleaf lettuce, pea shoots, micro radish, broccoli sprouts, and cherry- and slicer tomatoes. “What we grow comes from direct feedback from our subscribers. Tomatoes are a great example, as we started trialing them in mid-2020, delivered samples to chefs, produce managers, and subscribers,” notes Clayton. He says that their feedback helped to bring the tomatoes to market 3 months earlier than expected, which has continued to add to Nebullam’s revenue. Now, the company is looking at peppers, cucumbers, strawberries, and spinach, which are subscriber requests.

Read the rest of the article here

For more information:

Clayton Mooney, founder

Nebullam

c@nebullam.com

www.nebullam.com

Can A New Initiative Spur Agricultural Revolution In Alaska?

When Eva Dawn Burk first saw Calypso Farm and Ecology Center in 2019, she felt enchanted. Calypso is an educational farm tucked away in a boreal forest in Ester, Alaska, near Fairbanks

By Max Graham

July 6, 2021

This story by Max Graham originally appeared in High Country News and is republished here as part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.

When Eva Dawn Burk first saw Calypso Farm and Ecology Center in 2019, she felt enchanted. Calypso is an educational farm tucked away in a boreal forest in Ester, Alaska, near Fairbanks. To Burk, it looked like a subarctic Eden, encompassing vegetable and flower gardens, greenhouses, goats, sheep, honeybees, a nature trail, and more. In non-pandemic summers, the property teems with local kids and aspiring farmers who converge on the terraced hillside for hands-on education.

Calypso reminded Burk, 38, who is Denaakk’e and Lower Tanana Athabascan from the villages of Nenana and Manley Hot Springs, of her family’s traditional fish camp in the Alaskan Interior, where she spent childhood summers. “I just felt like I was home,” Burk said. “[Calypso] really spoke to my heart.”

Eva Dawn Burk stands on the bank of the Tanana River in late April in her home village of Nenana, AK. Burk is a graduate student at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and is developing biomass-heated greenhouses for rural Native communities. Photo credit: Brian Adams / High Country News

When Burk was still young, though, her family drifted away from its traditions. As fish stocks dropped and the cost of living rose, they stopped going to fish camp. Burk studied engineering in college and, in 2007, found a stable job in the oil and gas industry at Arctic Slope Regional Corporation. But after she had a series of revelatory dreams — first of an oil spill, then of a visit from her departed grandmothers — and heard elders discussing threats to traditional food sources, Burk committed herself to advocating for tribal food sovereignty.

A few months after her first visit to Calypso, Burk became a graduate student at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, where she currently researches the link between health and traditional food practices. In 2020, Burk received the Indigenous Communities Fellowship from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to develop a business model for implementing biomass-heated (or wood-fired) greenhouses in rural Native villages. The greenhouses will grow fresh produce year-round while also creating local jobs and mitigating wildfire risk.

The driveway leading to Calypso Farm in late April as the last of the winter’s snow melts. Photo credit: Brian Adams / High Country News

Now, Burk is partnering with Calypso to promote local food production and combat food insecurity in Alaska Native communities. The initiative involves building partnerships with tribes to teach local tribal members, particularly youth, about agriculture and traditional knowledge. The project is still in its infancy, but Burk hopes to help spur an agricultural revolution in rural Native villages, where food costs are exorbitant and fresh produce is hard to come by.

Alaska Native communities face numerous challenges to food security. Many communities are accessible only by boat or plane, and some lack grocery stores altogether. The residents of Rampart, a small Athabascan village on the Yukon River, have to order groceries from Fairbanks, delivered by plane at 49 cents per pound plus tax, or else travel there to shop — a $202 round-trip flight, a five-hour trip by boat and truck, or a four-and-a-half-hour drive overland. Sometimes orders are delayed due to weather, or because the delivery plane is full, said Brooke Woods, chair of the Yukon River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, who is from Rampart. “You’re getting strawberries that are molded,” Woods said. “And you’re just throwing them away in front of an elder.”

Grocery store in Nenana, AK. Photo credit: Brian Adams / High Country News

Indigenous families that depend on traditional foods, such as salmon and moose, have to contend with rapidly shifting ecosystems and declining wild food sources, largely due, according to Indigenous leaders as well as several studies, to climate change. Perhaps the biggest food challenge is the dizzying system of joint wildlife management among Alaskan tribes and the state and federal governments. In 2020, the Inuit Circumpolar Council reported that Alaskan Inuit “recognized the lack of decision-making power and management authority to be the greatest threat to Inuit food security.” Last summer, during a pandemic-related food crisis, the Tlingit village of Kake had to get federal approval before tribal members could hunt on the land around their community, as High Country News reported.

“This is work that has to be done by us, by people in the community, not from the outside.”

Despite the clear and unique obstacles to food security for many families, a 2018 review in the International Journal of Circumpolar Health found that “studies that estimate the prevalence of food insecurity in remote Alaska Native communities … are virtually absent from the literature.” The limited and outdated data available indicates that about 19 percent of the Alaska Native population — 25 percent in rural areas — experiences food insecurity, compared to 10.5 percent of the total population nationwide, according to the USDA.

Burk is not the first to look to growing food locally as a solution. Over the last two decades, several Indigenous-led agricultural projects have emerged across Alaska. Burk’s vision, however, is particularly ambitious: In addition to building community gardens and year-round greenhouses, she wants to form a statewide network of Indigenous farmers.

Susan Willstrud, co-founder of Calypso Farm, waters seedlings in late April. Photo credit: Brian Adams / High Country News

In late April, Burk met with Deenaalee Hodgdon and Calypso Farm staff on a sunny deck at the farm, just yards from swarms of bees delivering pollen to their hungry hive. Hodgdon, 25, founder of On the Land Media, a podcast that centers Indigenous relationships with land, is collaborating with Burk and Calypso on the farmer training initiative.

Hodgdon, who is Deg Xit’an, Sugpiaq, and Yupik, worked at Calypso as a farmhand for a summer after sixth grade. Calypso provided them a new language for working with the land. At one point during the meeting, Hodgdon motioned toward the farmland and said, “This could literally feed a lot of our villages in Alaska.”

Burk’s first target is Nenana, her hometown, where she is working with the tribal office, Native corporation, and city government to implement a community-run biomass-heated greenhouse.

The biomass-heated greenhouse at the Tok school in Tok, Alaska. Photo credit: Brian Adams / High Country News

The project was inspired by a wood-fueled energy system and heated greenhouse built almost a decade ago in Tok, about a four-hour drive southeast of Nenana. Many Alaskan towns have productive gardens. The growing season lasts barely 100 days, however, and only a handful have year-round growing capacity. The Tok School came up with a clever solution: The facility is powered by a massive wood boiler and steam engine, and the excess heat is piped into the greenhouse. The school has a wide array of hydroponics.

Inside the greenhouse, you could easily forget you’re in Alaska. On a brisk day in late April, when the ground outside was brown and barren, dense green rows of tomato plants, lettuce, zucchini and other salad crops reached towards the 30-foot ceiling. During one week in April, when outside temperatures dropped below minus-30 degrees Fahrenheit, greenhouse manager Michele Flagen said she harvested 75 pounds of cucumbers that the students had helped plant. Altogether, the greenhouse provides fresh produce for the district’s more than 400 students.

Nenana is at least a year away from installing its biomass system, but Burk plans to begin planting a garden next spring if the greenhouse is not yet ready.

Jeri Knabe, administrative assistant at Nenana’s tribal office, loves Burk’s plan. “I can’t wait. I’m very excited,” she said. High food costs have long been a challenge for Nenana residents, she explained: “When I was growing up, we were lucky to get an orange.”

Eva Dawn Burk’s children play with a friend in the Tanana River in Nenana, AK in late April. Photo credit: Brian Adams / High Country News

Burk and Hodgdon hope to address Native food security statewide, and local community members like Knabe are central to their initiative. During their meeting at Calypso, Burk and Hodgdon emphasized that grassroots agriculture is more than a way to feed people; it’s also another step towards tribal sovereignty and self-management. “This is work that has to be done by us, by people in the community, not from the outside,” Hodgdon said.

In August 2021, the group will host its first training program for Alaska Native gardeners at Calypso. With so many greenhouses and gardens yet to be built, Burk’s latest dream has only just begun to grow.

Lead Photo: A student-led strawberry-growing project inside the greenhouse at the Tok School. The biomass-heated greenhouse grows enough produce to feed the district’s students year-round. Photo credit: High Country News

Farmers Already Forced To Abandon Crops As Additional Water Restrictions Loom

Bringing into focus some of the California crop losses caused by the 2021 drought, Western Growers has released a series of videos called “No Water = No Crops”

By Tom Karst

July 12, 2021

Bringing into focus some of the California crop losses caused by the 2021 drought, Western Growers has released a series of videos called “No Water = No Crops.”

The videos feature three California farmers who talk about the losses they are suffering this year.

“This is one of the most difficult decisions I’ve had to make in a long time,” Joe Del Bosque of Del Bosque Farms, Firebaugh, Calif., who sacrificed his asparagus field that still had five years’ productivity left, said in one video. “Seventy people are going to lose their jobs here. Next year, there will be no harvest here. Those 70 people lose two months of work. It’s a very difficult hit for them.”

Another video features Ross Franson of Fresno, Calif.-based Woolf Farming.

“Around this time of year, we’d normally be prepping for harvest,” Franson said in the video.

The farm has started knocking down almond trees in its 400-acre orchard, he said.

“But due to the dire drought that’s going on in the state of California right now, we made the decision to pull these trees out simply because we didn’t have the water to irrigate them.”

“These trees are all dead, and they shouldn’t be,” Jared Plumlee of Booth Ranches said in one video. The company produces citrus in Orange Cove, Calif., and destroyed 70 acres of trees because of the drought.

“It’s just a shame. This block had probably 20 years of productive life, and we were forced to push it out.”

Western Growers president and CEO Dave Puglia said in a news release that the future of agriculture in California is being compromised by the regulatory uncertainty of water deliveries to farms.

“Is that really what you want? Do you want a bunch of dust blowing through the center of the state interrupted by fields of solar panels, which don’t employ many people?” Puglia said in the release.

“It is a question that needs to be posed to Californians, generally, and their political leaders. Is that what you want? Because that is the path you are on.”

Lead Photo: Joe Del Bosque of Del Bosque Farms, Firebaugh, Calif. points to a melon field that was plowed under because of the drought.

The Collaborative Farm: Where Agriculture Meets The Entertainment World

The Collaborative Farm is an emerging destination in Milwaukee that survives as the rebrand of an organization formally known as Growing Power. The Farm is redefining urban agriculture and how the entertainment industry can impact its operations remarkably to sustain several communities

By GetNews

July 13, 2021

The Collaborative Farm is an emerging destination in Milwaukee that survives as the rebrand of an organization formally known as Growing Power. The Farm is redefining urban agriculture and how the entertainment industry can impact its operations remarkably to sustain several communities. The new and improved organization was made possible by Tyler Schmitt, best known to his peers as Tymetravels. His phenomenal vision to put together agriculture and music to expand urban farming has been making waves, making his novel initiative an extraordinary breakthrough.

Schmitt majored in Entrepreneurship with a minor in Sustainability at the University of St. Thomas then later moved to live in the national parks in Wyoming. When Growing Power collapsed, Schmitt came home from Jackson Hole to lend a hand to Will Allen and his father Tom Schmitt to solve the intricate issues involved in urban farming—from solar aquaponics to increasing food production while keeping operations sustainable.

Schmitt developed Ultimate Farm Collaborative to redesign not just farms but also cities in the near future. Collab Official, on the other hand, is the record label he created in order to unite various music artists under the umbrella of an extraordinary cause. The Farm Music Festival is its annual event, which is designed to generate funds to sustainably operate the farm.

This coming October 1–3, Milwaukee’s last remaining farm will be hosting a music festival to create awareness on the value of urban farming through hip-hop and EDM music. Schmitt hopes that the upcoming event will make a difference in the lives of urban farmers. The upcoming event will also give the good people of Milwaukee an opportunity to experience The Collaborative Farm up close. When music meets agriculture, the possibilities are out of this world.

The Collaborative Farm has a whole lot of surprises in store for the future as it is in the process of developing and recruiting a solid and hardworking team that will help it realize its goals. In the coming months, it will open an art studio, which will also be a coffee shop. The coffee shop will be the front store to increase foot traffic day in and out long-term. Additionally, it is working on establishing the vertical farm that Growing Power was positioned to pursue in the past.

Moreover, the founder of Ultimate Farm Collaborative sees the company staying with The Collaborative Farm long-term. In the next couple of years, it will either purchase or design a second facility. The annual music festival at The Collaborative Farm will continue and expand as a creative label through the efforts of Collab Official.

The novel idea behind The Collaborative Farm serves as an inspiration to those who have been supporting urban farming and those who wish to try sustainable living by growing their own produce. As the entertainment aspect of the whole operation continues to fund the needs of the farm that provides produce for locals, Tyler Schmitt hopes to continue to make promising collaborations that will impact the community significantly in the coming years.

Media Contact

Company Name: Ultimate Farm Collaborative Inc.

Contact Person: Tyler Schmitt

Email: Send Email

Phone: 4145874320

Country: United States

Website: http://www.ultimatecollab.com

Skills Shortages In The Food Industry

Just like in other parts of society, there is rapid technological development and digitalisation in the food industry. It places demands on completely new skills and the food industry also needs to become better at attracting and taking care of young people, new arrivals and people with different backgrounds.

June 10, 2021

Bengt Fellbe, Program Leader, SSEC, Swedish Surplus Energy Collaboration, discusses the importance of training people with the right skills to work within the Swedish sustainable food industry

There is a lot of talk about circular and sustainable processes in the modern food industry. There is a lot of work and investment in innovations that revolve around digitization, AI, automation, aquaponics, vertical cultivation, circular bio-based economic models – and that’s good. BUT, without a skilled workforce, the development will not take place.

Region Skåne

Region Skåne in southern Sweden has perceived the situation and is announcing project funds to help. This is how they describe the situation.

Photographs by Erik Lundgren, Ljusgårda AB

The food industry and agriculture have always been the heart of Skåne. Skåne accounts for about a third of Sweden’s food production. Food is also part of our Scanian identity. This is how we want it to be in the future as well. But there is a concrete threat.

The Scanian food industry and agriculture have a hard time finding the right people. If we do not act now, we may soon have serious problems in this Skåne industry. We must think new.

There are several reasons for all this. Just like in other parts of society, there is rapid technological development and digitalisation in the food industry. It places demands on completely new skills and the food industry also needs to become better at attracting and taking care of young people, new arrivals and people with different backgrounds.

There are jobs. But it is the matching between those who want to hire and those who are looking for work that is lacking. In other words: we are no longer training the right people right for the food industry.

Initiatives

There are, of course, several different good initiatives throughout Sweden that SSEC has initiated.

In the municipality of Bjuv, “Recruitment training” has been carried out aimed at the food industry in collaboration between the company in question with recruitment needs and the Swedish Public Employment Service. A company-friendly tool that the employment service in Sweden has in its toolbox. The company that has skills needs and needs to recruit is involved in the entire process together with the employment service.

SSEC has been helpful in developing requirements profile and course content together with companies in the industry, which has resulted in a Higher Vocational Education (HVE) – “Sustainable food entrepreneur”.

About the Higher Vocational Education “Sustainable food entrepreneur”

By studying to be a Sustainable Food Entrepreneur, you will be involved in developing food from a sustainable, circular perspective. You will gain both theoretical and practical knowledge about the Swedish sustainability work. In addition, you get the opportunity to try out your own ideas in consultation with professional food producers.

The education gives you a basic competence in sustainability and different types of food production, as well as the opportunity to specialise through LIA internships, (Learning at Work).

You also gain knowledge about, for example, the global sustainability goals, sustainable plant breeding, entrepreneurship, sustainable animal husbandry and hygiene and safety.

Ljusgårda in Tibro municipality is an innovative company in vertical cultivation. The company is expanding enormously to meet the needs of the market and needs to recruit staff within several competence levels. These are horticulturists and agronomists with a University degree, operations managers from the Higher Vocational Education, preferably with competence and experience of the technology behind indoor cultivation-vertical cultivation, and a large number of employees in production. In this technology-intensive horticulture, there are changing requirements for competence compared with a traditional horticulture. These are completely different conditions in that the production in this case is automated, digitized, and uses the latest technology in measurement and sensor technology. Another important factor is that it is a year-round business and cannot rely on seasonal employees.

In the Skaraborg region and Tibro municipality, SSEC has therefore initiated a close collaboration between the company, the Swedish Public Employment Service, and the municipality’s labour market unit. The aim is to build structures that support and reflect the need for skills supply in the food industry in both the short and long term. In Northwestern Skåne, 11 municipalities collaborate in adult education. The municipality of Bjuv, together with the municipality of Åstorp, will this autumn, offer basic adult education aimed at the food industry. The goal is to supply a strongly growing innovative industry with competent production personnel in the long term.

As I said, the agrarian industry and the food industry’s technological development are moving at a furious pace towards being both sustainable and competitive. But, without competent employees, we will not get anywhere.

We cannot miss this golden opportunity – with the right education, we help thousands of people to work and increase their quality of life, while companies, municipalities, regions, and countries become socially, economically, and climate-sustainable.

Please note: This is a commercial profile

© 2019. This work is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Bengt Fellbe

Acting Program leader

SSEC, Swedish Surplus Energy Collaboration

Phone: +46 709585019

Email: bengt.fellbe@gmail.com

Website: Visit Website

Where Vertical Farming and Affordable Housing Can Grow Together

Some vertical farms grow greens in old warehouses, former steel mills, or other sites set apart from the heart of cities. But a new series of projects will build multistory greenhouses directly inside affordable housing developments

Some vertical farms grow greens in old warehouses, former steel mills, or other sites set apart from the heart of cities. But a new series of projects will build multistory greenhouses directly inside affordable housing developments.

“Bringing the farm back to the city center can have a lot of benefits,” says Nona Yehia, CEO of Vertical Harvest, a company that will soon break ground on a new building in Westbrook, ME, that combines a vertical farm with affordable housing. Similar developments will follow in Chicago and in Philadelphia, where a farm-plus-housing will be built in the Tioga District, an opportunity zone.

Inside each building, the ground level will offer community access, while the greenhouse fills the second, third, and fourth floors, covering 70,000 square feet and growing around a million pounds of produce a year. (The amount of housing varies by site; in Maine, there will be only 15 units of housing, though the project will create 50 new jobs.)

In Chicago, there may be a community kitchen on the first level. In each location, residents will be able to buy fresh produce on-site; Vertical Harvest also plans to let others in the neighborhood buy greens directly from the farm. While it will sell to supermarkets, restaurants, hospitals, and other large customers, it also plans to subsidize 10% to 15% of its harvest for local food pantries and other community organizations.

“By creating a large-scale farm in a food desert, we are creating a large source of healthy, locally grown food 365 days a year,” Yehia says.

Forget Politics, Danny Ayalon Wants to Effect Change on The Ground

Having transitioned from politics to agriculture, Danny Ayalon shares how vertical farming, which provides fresh fruits and vegetables all year round, and lab-grown meat can rehabilitate the environment and dramatically reduce household expenditures

Having transitioned from politics to agriculture, Danny Ayalon shares how vertical farming, which provides fresh fruits and vegetables all year round, and lab-grown meat can rehabilitate the environment and dramatically reduce household expenditures.

Image from: Yehoshua Yosef

The coronavirus pandemic has drawn attention to humankind's carbon footprint. More than ever before we ask ourselves, how can we become more sustainable? Can we prevent pollution? How can we minimize waste? What about lowering emission levels? Will there be enough food for everyone in the future?

Danny Ayalon, a former ambassador and foreign policy adviser to three prime ministers-turned entrepreneur, believes that the answer to many of the world's problems lies in modern agriculture.

Having transitioned from politics to agriculture, he works with Future Crops, an Amsterdam-based company focused on vertical farming – the practice of growing crops in vertically stacked layers that often incorporates controlled-environment agriculture, which aims to optimize plant growth – and MeaTech, a company that creates lab-grown meat.

"Ever since the coronavirus came into our lives, we realized that man is not in charge of the universe," Ayalon told Israel Hayom.

"Our control over the forces of nature, of Earth, of our future is more limited than we had thought. And when we are no longer in charge of the world, only three things guarantee our lives here: food, water, and energy security. Food, water, and energy are three resources that can be depleted and therefore literally cast a cloud on our world.

"Experts have come to a conclusion that one of the most important fields to focus on is agriculture, and indeed we are currently witnessing the most significant agricultural revolution ever since the first agricultural revolution that took place about 10,00 years ago."

Q: Back then, in the first agricultural revolution, there was a need for a lot of land.

"But today we have technology. The name of the game is to reach maximum output with minimum input in the smallest space possible. This is the holy grail of the new revolution. And that is how technology enters the picture. To grow fruits, vegetables and spices today requires lots of space. The technology we developed at Future Crops allows us to minimize the space, increase production and redefine the food supply chain."

Q: How exactly?

"We have a nine-story hangar in Amsterdam to grow crops like coriander, basil, dill, and parsley. It has LED lights, and each plant gets exactly the amount of light it needs. We are the plant psychologists, [we] listen to all its needs and do everything to make sure the plant grows in the most optimal way.

Image from: Future Crops

"If it lacks something, it immediately receives water. Everything is done without a human's touch. We use algorithms and big data in collaboration with world-class researchers from the Weizmann Institute. It is essentially the application of vertical farming, growing various crops in vertically stacked layers, in enclosed structures, on soil platforms.

"For example, if it takes a month to grow lettuce in an open field, in a vertical farm, it takes two weeks, half that time. There's also a significant reduction in water consumption, and no pesticides or sprays are used at all. Also, the produce is available in all seasons; it does not depend on the temperature. Whoever likes mangos and strawberries, for example, will be able to enjoy them all year round."

Q: So if produce is grown faster and within a smaller space, is it going to cost less?

"The prices might be a bit higher today because this technology and the various infrastructures require an economic return of the initial investment in them. With time, the process will become more efficient, and the investments will be repaid, so in the end, the prices that the consumer will need to pay will be lower than today.

"Let me give you a simple example. Do you know how much a kilogram [2.2 pounds] of basil costs in Europe today? €90 ($108). In Israel, the price is €20 ($24). In the [United Arab] Emirates, where almost everything connected to food is imported – the prices go accordingly as well. Once you have more innovative vertical farms, consumers will pay much less."

Q: Should we expect vertical farm skyscrapers to pop up all over?

"I'm not sure that we will need skyscrapers, as with time the facilities will become smaller. Imagine that in every supermarket there will be a vertical produce stand with all the vegetables and spices, and later also fruits which you pick on the spot, without the need to move the produce from place to place. That is why vertical farming is also called urban farming, meaning there is no need for fields; you can grow [produce] on the rooftop. No resource limits you."

Q: What about the taste?

"Ours is a fresher and tastier product. I ought to give credit to the Weizmann Institute here. The challenge for them wasn't the quality of the vitamins but the taste, and they managed to achieve a great taste. In the Netherlands, Future Crops already sells parsley, and it tastes outstanding."

Q: Regular parsley lasts for about two weeks in the fridge. What about Future Crops parsley?

"Our parsley has a two-month shelf life, and it does not oxidize within a week or two."

Q: If every country will be self-reliant in terms of agriculture, do you think it will affect relations between countries?

"Economies will become self-sufficient eventually, which will ensure security with far fewer conflicts. There is less and less water in the Middle East, which might someday lead to tensions. We hope technology will reduce the tensions between countries, and territory will be less critical. Our world faces crucial challenges. Food and water security have the potential to either divide or bring us together and ensure our long-term existence.

"By the way, in every developed Western country, like the United States, Australia, and also in Europe, issues of food security, climate, and greenhouse emissions are on the top of the political agenda. We are not talking about it [in Israel,] as security and foreign affairs take the central stage, but Israel does have a lot to offer here."

Q: Do we have the potential to become the Silicon Valley of advanced agriculture?

"Israel takes tremendous pride in its actions that help save the world. Will we become the Silicon Valley of agriculture? There is no doubt about it. We can already see foreign investors who come here to look for opportunities, including my business partner Lior Maimon, co-founder and CEO of Silver Road Capital, and Steven Levin, one of the leaders of the US food industry. Silver Road Capital is a holdings and financial advisory firm with a broad portfolio of high-tech companies, as well as agricultural and food technologies, and represents international companies and funds in investments in Israel and the world.

"Future Crops's goal is to raise 35 million shekels on the Israeli stock exchange to invest in enlarging the existing facilities and [set up] other production lines and facilities in Europe and other continents. We cooperate with the Albert Heijn supermarket chain [in the Netherlands] and a leading food chain in France."

Q: Vertical farming is estimated at $3 billion. Google and Amazon have invested hundreds of millions in the field as well. What is their goal?

"A simple answer would be profit. A longer answer is that they [large corporations] understand that food has the highest demand. People cannot live without food and water, and Google and Amazon understand that potential."

Q: US President Joe Biden took office with the largest team of climate experts ever. That ought to give the field momentum.

"Green energy and vertical farming will get a considerable boost. Climate change and green energy are well-rooted in the Democratic Party's ideology.

"It is also possible that large companies entered the agriculture fields precisely because of the Biden administration; they are worried about their future. They are afraid of a certain dismantling, so focusing on secondary fields is part of a security scenario for them."

Q: Biden also wants to address greenhouse emissions, which are the result of the food production industry, mainly meat. Are Amazon and Google's food counterparts - McDonald's and Burger King - looking for meat substitutes?

"Firstly, cultured [lab-grown] meat does not require grazing land, cows do not need to be fed, and so much land can instead be turned into forests that support the environment. This is an optimistic industry that leaves us with a better world.

"As for the meat alternatives market, there are two major companies in the US that produce plant-based protein, Beyond Meat, and Impossible Foods.

"Impossible's burgers are already at Burger King, McDonald's has partnered up with Beyond Meat, and last November, it announced that it would create its own plant-based burger.

"The problem is that pea protein [used in plant-based burgers,] does not have all the amino acids that animal protein contains. Also, they need to add additives to supplement for taste and smell.

"At MeaTech, where I'm a director, we are on our way to producing animal meat, cultured meat, real stakes: we take a cow's own stem cell from which meat can be produced in almost unlimited quantities. We also use 3D digital printing technology. And we also created a thin layer of meat, carpaccio. Needless to say, no cow was harmed in the process."

Image from: MeaTech

Q: Why do you use 3D printers?

"Because there is no need for a human being's involvement. It is relevant now during the coronavirus pandemic when the food supply chain is disrupted. With such printers, your production can continue without delays, whenever you want.

Also, it is theoretically possible to provide food for space flights. Astronauts who go out into space will not have to take food with them; rather, they will be able to produce it on the spot.

"People understand that crises like the coronavirus can disrupt the supply chain and are looking for alternatives. A 3D printer allows restaurants, supermarkets, and butcher shops to have meat without relying on the supply chain."

Q: The death rate from obesity is higher than the death rate from hunger. How will cultured meat affect these statistics?

"It is possible to create meat with much less fat and more protein in each portion and add various nutrients in the future to strengthen the immune system and prevent disease. This, of course, requires a lot of research and approvals. Just like there's talk about customized medicine, so it will be possible to produce food that suits a person's genetic structure and body in the most optimal way."

Q: Will the cost of this meat also be optimal?

"They will cost more in the beginning compared to regular meat because there are initial costs that have to be repaid. When it becomes a mass production, prices will drop over time."

Q: With your vast experience in politics, what do you think of Israeli politics these days? Do you ever consider a political comeback?

"No election campaign goes by without someone making me an offer [to return to politics] but I'm not interested. Unfortunately, the Israeli government, and all governments in the Western world, have not been able to run their countries properly in recent years.

"For example, more of the government's national taks are transitioning to the private market or the third sector. We see that associations [are the ones] who take care of the needy, establish settlements in the Negev and in the Galilee, bring immigrants to Israel and provide Israelis with information. All these things should be done by the government.

"The Israeli government lacks vision, ideologies, every matter is personal and is charged with negative sentiments. If I do return one day, it will only happen after we change the government system which will take its power from small [political] parties.

"In my opinion, we need to transition to a regional choice, by district. This will result in higher quality politicians. How so? Because whoever wants to be elected will need to run and convince the people who live in his area and district, and they are the ones who know his activities best. Also, closed primaries should be avoided because they make all kinds of deals possible. That needs to change."

Vertical Farming: Ugandan Company Develops Solution for Urban Agriculture

We speak to Lilian Nakigozi, founder of Women Smiles Uganda, a company that manufactures and sells vertical farms used to grow crops in areas where there is limited space

We speak to Lilian Nakigozi, founder of Women Smiles Uganda, a company that manufactures and sells vertical farms used to grow crops in areas where there is limited space.

Image from: How We Made It in Africa

1. How Did You Come Up with the Idea to Start Women Smiles Uganda?

Women Smiles Uganda is a social enterprise formed out of passion and personal experience. I grew up with a single mother and eight siblings in Katanga, one of the biggest slums in Kampala, Uganda. I experienced hunger and poverty where we lived. There was no land for us to grow crops and we didn’t have money to buy food. Life was hard; we would often go to sleep on empty stomachs and our baby sister starved to death.

Growing up like that, I pledged to use my knowledge and skills to come up with an idea that could solve hunger and, at the same time, improve people’s livelihoods, particularly women and young girls living in the urban slums. In 2017, while studying business at Makerere University, I had the idea of developing a vertical farm. This came amid so many challenges: a lack of finance and moral support. I would use the money provided to me for lunch as a government student to save for the initial capital of my venture.

I managed to accumulate $300 and used this to buy materials to manufacture the first 20 vertical farms. I gave these to 20 families and, in 2018, we fully started operations in different urban slums.

2. Tell Us About Your Vertical Farms and How They Work.

Women Smiles vertical farms are made out of wood and recycled plastic materials. Each unit is capable of growing up to 200 plants. The product also has an internal bearing system which turns 360° to guarantee optimal use of the sunlight and is fitted with an inbuilt drip irrigation system and greenhouse material to address any agro-climatic challenges.

The farms can be positioned on a rooftop, veranda, walkway, office building or a desk. This allows the growth of crops throughout the year, season after season, unaffected by climatic changes like drought.

In addition, we train our customers on how to make compost manure using vermicomposting and also provide them with a market for their fresh produce.

Image from: How We Made It in Africa

3. Explain Your Revenue Model.

Women Smiles Uganda generates revenue by selling affordable, reliable and modern vertical farms at $35, making a profit margin of $10 on each unit. The women groups are recruited into our training schemes and we teach them how to use vertical farming to grow crops and make compost manure by vermicomposting. Women groups become our outgrowers of fruits and vegetables. We buy the fresh produce from our outgrowers and resell to restaurants, schools and hotels.

We also make money through partnering with NGOs and other small private organisations to provide training in urban farming concepts to the beneficiaries of their projects.

4. What Are Some of the Major Challenges of Running This Business?

The major challenge we face is limited funds by the smallholder farmers to purchase the vertical farms. However, we mitigate this by putting some of them into our outgrower scheme which helps them to generate income from the fresh produce we buy. We have also linked some of them to financial institutions to access finance.

5. How Do You Generate Sales?

We reach our customers directly via our marketing team which moves door to door, identifying organised women groups and educating them about the benefits of vertical farming for improved food security. Most of our customers are low-income earners and very few of them have access to the internet.

However, we do also make use of social media platforms like Facebook to reach out to our customers, especially the youth.

In addition, we organise talk shows and community gatherings with the assistance of local leaders with whom we work hand in hand to provide educational and inspirational materials to people, teaching them about smart agriculture techniques.

6. Who Are Your Main Competitors?

Just like any business, we have got competitors; our major competitors include Camp Green and Spark Agro-Initiatives.

Image from: The Conversation

7. What Mistakes Have You Made in Business and What Did You Learn From Them?

As a victim of hunger and poverty, my dream was for every family in slums to have a vertical farm. I ended up giving some vertical farms on credit. Unfortunately, most of them failed to pay and we ended up with huge losses.

This taught me to shift the risk of payment default to a third party. Every customer who may need our farms on credit is now linked to our partner micro-finance bank. By doing this, it is the responsibility of the bank to recover the funds from our customers and it has worked well.

8. Apart from This Industry, Name an Untapped Business Opportunity in Uganda.

Manufacturing of cooler sheds for the storage of perishable agricultural produce is one untapped opportunity. Currently, Ugandan smallholder farmers lose up to 40% of their fresh produce because of a lack of reliable cold storage systems.

Providing a cheap and reliable 24/7 cold storage system would dramatically reduce post-harvest losses for these farmers.

2-Acre Vertical Farm Run By AI And Robots Out-Produces 720-Acre Flat Farm

A San Fransisco start-up is changing the vertical farming industry by utilizing robots to ensure optimal product quality

Plenty is an ag-tech startup in San Francisco, co-founded by Nate Storey, that is reinventing farms and farming. Storey, who is also the company’s chief science officer, says the future of farms is vertical and indoors because that way, the food can grow anywhere in the world, year-round; and the future of farms employ robots and AI to continually improve the quality of growth for fruits, vegetables, and herbs. Plenty does all these things and uses 95% less water and 99% less land because of it.

In recent years, farmers on flat farms have been using new tools for making farming better or easier. They’re using drones and robots to improve crop maintenance, while artificial intelligence is also on the rise, with over 1,600 startups and total investments reaching tens of billions of dollars. Plenty is one of those startups. However, flat farms still use a lot of water and land, while a Plenty vertical farm can produce the same quantity of fruits and vegetables as a 720-acre flat farm, but on only 2 acres!

Storey said:

“Vertical farming exists because we want to grow the world’s capacity for fresh fruits and vegetables, and we know it’s necessary.”

Plenty’s climate-controlled indoor farm has rows of plants growing vertically, hung from the ceiling. There are sun-mimicking LED lights shining on them, robots that move them around, and artificial intelligence (AI) managing all the variables of water, temperature, and light, and continually learning and optimizing how to grow bigger, faster, better crops. These futuristic features ensure every plant grows perfectly year-round. The conditions are so good that the farm produces 400 times more food per acre than an outdoor flat farm.

Storey said:

“400X greater yield per acre of ground is not just an incremental improvement, and using almost two orders of magnitude less water is also critical in a time of increasing environmental stress and climate uncertainty. All of these are truly game-changers, but they’re not the only goals.”

Another perk of vertical farming is locally produced food. The fruits and vegetables aren’t grown 1,000 miles away or more from a city; instead, at a warehouse nearby. Meaning, many transportation miles are eliminated, which is useful for reducing millions of tons of yearly CO2 emissions and prices for consumers. Imported fruits and vegetables are more expensive, so society’s most impoverished are at an extreme nutritional disadvantage. Vertical farms could solve this problem.

Storey said:

“Supply-chain breakdowns resulting from COVID-19 and natural disruptions like this year’s California wildfires demonstrate the need for a predictable and durable supply of products can only come from vertical farming.”

(Credit: Reuters)

Plenty’s farms grow non-GMO crops and don’t use herbicides or pesticides. They recycle all water used, even capturing the evaporated water in the air. The flagship farm in San Francisco is using 100% renewable energy too.

Furthermore, all the packaging is 100% recyclable, made of recycled plastic, and specially designed to keep the food fresh longer to reduce food waste.

Storey told Forbes:

“The future will be quite remarkable. And I think the size of the global fresh fruit and vegetable industry will be multiples of what it is today.”

Plenty has already received $400 million in investment capital from SoftBank, former Google chairman Eric Schmidt, and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos. It’s also struck a deal with Albertsons stores in California to supply 430 stores with fresh produce.

Ideally, the company will branch out, opening vertical farms across the country and beyond. There can never be too many places graced by better food growing with a less environmental cost.

Here’s a TechFirst podcast about the story behind Plenty:

Published by Dani Kliegerman for iGrow.News

Vera Vertical Farming Technology Introduced in Finland’s Largest Retail Group

Finland’s largest retailer is now carrying produce farmed in vertical-farming centers to provide ultra-fresh produce year round.

Netled And Pirkanmaan Osuuskauppa Sign A New Long-Term Cooperation Agreement

In the photo: Ville Jylhä, COO of Pirkanmaan Osuuskauppa

Netled has entered into a significant long-term cooperation agreement with Pirkanmaan Osuuskauppa, a regional operator of S-Group, the largest retail chain in Finland.

Netled’s Vera Instore Premium Growing Cabinets, offering a range of herbs and salads, will now be a regular feature in Prisma retail stores in the Pirkanmaa area. Herbs and some of the leafy greens are grown in-store in the cabinets, and are harvested directly off the shelf. The growing conditions are fully automated and controlled remotely.

The newly opened Prisma Pirkkala is Finland’s first hypermarket to launch the new Vera Instore Cabinets. In addition, Netled will deliver to the hypermarket salads and herbs grown on its own vertical farm nearby, thereby allowing customers to get same-day harvested herbs and salads all year round.

”With this newly formed collaboration we can offer consumers fresh, ultra-locally produced products and at the same time introduce them to vertical farming as a method of ecological, urban farming”, says Ville Jylhä, COO of Pirkanmaan Osuuskauppa.

S-Group is a customer-owned Finnish network of companies in the retail and service sectors, with more than 1 800 outlets in Finland. The group offers services in areas such as, supermarket trade, department store, and speciality store trade. As the largest retail group in Finland, S-Group’s main focus is also on sustainable food and innovative ways it can offer healthy and responsibly produced food to its customers.

Netled Ltd. is Finland’s leading provider of turn-key vertical farming systems and innovative greenhouse lighting solutions.

”As the leading vertical farming technology provider in Finland, we have developed an extensive range of products for all segments of vertical farming. Instore growing systems are a rapid-growth segment, and our cutting-edge Vera technology puts us at the forefront of the instore space”, says Niko Kivioja, CEO of Netled Ltd.

“The agreement with Pirkanmaan Osuuskauppa is just the latest proof of concept, and is also a clear signal to potential customers, investors and other global partners that Vera technology is a game changer.”

18th December 2020 by johannak

More information:

Niko Kivioja

CEO, Netled Ltd

+358 50 360 8121

Robert Brooks, Investor Relations and Communications Manager

+358 50 484 0003

AppHarvest’s Mega-Indoor Farm Offers Economic Alternative To Coal Mining For Appalachia

AppHarvest is taking advantage in the new wave of high-tech agriculture to help feed a growing population and increase domestic work opportunities in a sustainable manner.

Inside AppHarvest's 60 acre state-of-the art indoor farm in Morehead, KY.

In the first year of business, Jonathan Webb and his growing team at AppHarvest are riding high on what he calls the “third wave” of sustainable development: high-tech agriculture, following the waves of solar energy and electric vehicles. Since launching the concept in 2017, Webb and AppHarvest have raised more than $150 million in funding while building and opening one of the largest indoor farms in the world on more than 60 acres near the Central Appalachian town of Morehead, Kentucky.

For Webb, who grew up in the area and has a background in solar energy and other large-scale sustainable projects, AppHarvest is both a homecoming and a high-profile, purpose-driven venture that addresses the need for additional production to feed a growing population and reduce imported produce.

Webb’s vision for AppHarvest was inspired in part by a National Geographic article on sustainable farming in the Netherlands, where indoor growing is part of a national agriculture network that relies on irrigation canals and other innovations. He traveled across the Atlantic Ocean to see the farmers in action, then decided it was a venture he wanted to pursue — in his home state of Kentucky, where the coal industry is in decline and unemployment levels are on the rise.

“Seeing that the world needs 50% to 70% more food by 2050, plus seeing that we’ve shifted most of our production for fruits and vegetables down to Mexico — produce imports were tripled in the last 10 to 15 years,” he says. “I would go to a grocery store, pick up a tomato, and it could be hard, discolored. That’s because it’s been sitting for two weeks on a semi truck, being bred for transportation. So first it was seeing the problem, then asking, ‘How do we solve the problem?’”

As part of my research on purpose-driven businesses and stakeholder capitalism, I recently talked with Webb about AppHarvest’s whirlwind initial year in business, successful investor fundraise, plans to go public, and B Corp Certification.

Good for Business, Good for Community

Jonathan Webb, founder and CEO of AppHarvest

“Where we’re doing what we’re doing is incredibly important. One of our biggest competitive advantages, frankly, is doing it here,” he says. “Some of the hardest-working men and women are the people in this region that power the coal mines, and all we’re trying to do is tap into that and harness that passion. It’s good for our business, but it's good for communities.”