Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Evaluating Real Estate For Indoor Agriculture

Several factors need to be evaluated before purchasing or leasing a piece of real estate for CEA. Will you build new construction or rehabilitate a vacant building? Are you building a large-scale greenhouse or a small, urban vertical farm?

March 17, 2021

Traditionally, buyers of agricultural real estate have focused on rural land where primary considerations for their farm include things such as soil quality, annual rainfall amounts, and adequate drainage. Increasingly, however, agriculture start-ups are moving indoors. Compared to field-based agriculture, indoor farming allows for more crop cycles, less water usage, and the farms can be located closer to the consumer. The considerations for an indoor, or controlled environment agriculture (CEA) operation are considerably different than for outdoor farms.

Assessing Potential Real Estate for CEA

Several factors need to be evaluated before purchasing or leasing a piece of real estate for CEA. Will you build new construction or rehabilitate a vacant building? Are you building a large-scale greenhouse or a small, urban vertical farm?

Environment

Weather and terrain are important for natural light greenhouse projects. The primary limiting factor to crop production in a greenhouse is low light intensity during the winter so consult with an Ag-extension service or other resource to get that information for a proposed location. Adequate acreage is a must for not only the greenhouses themselves but, also shipping and receiving space, a retention pond (if needed), and potentially even worker housing.

Spacing

For a vertical or urban farm in an enclosed building, important factors to consider include adequate square footage to allow for proper spacing between growing systems and enough room to move the towers (if mobile) for cleaning or maintenance. Additionally, a building should have a sufficient water supply and potentially drainage, a robust HVAC system and humidity controls, and a ceiling which is high enough for the growing towers. Although indoor farms using high efficiency LED lighting, these systems, combined with pumps, humidifiers, and HVACs can use significant amounts of electricity, a developer should carefully and conservatively estimate those costs prior to negotiating those terms with a landlord or electric company. Finally, the farm should be in close enough proximity to allow for routine delivery to local customers, be they restaurants, groceries, farmers markets, or Community Supported Agriculture distributors.

Labor

In both types of farms, labor availability and cost is a critically important consideration. The cost of wages for urban farms, even for unskilled workers, will likely be higher than that of rural areas. And in the case of any real estate development, ensure prior coordination with relevant agencies has been done on permits, licenses, and zoning regulations prior to signing any leases or closing on a land contract. Prior to starting a search for a CEA project, it’s wise to seek expert help from outside consultants who can save an indoor farm developer time, money, and aggravation.

Tags real estate, indoor agriculture, cea

Indoor Agtech: An Evolving Landscape of 1,300+ Startups

Our Indoor AgTech Landscape 2021 provides a snapshot of the technology and innovation ecosystem of the indoor food production value chain

March 17, 2021

Editor’s note: Chris Taylor is a senior consultant on The Mixing Bowl team and has spent more than 20 years on global IT strategy and development innovation in manufacturing, design, and healthcare, focussing most recently on indoor agtech.

Michael Rose is a partner at The Mixing Bowl and Better Food Ventures where he brings more than 25 years immersed in new venture creation and innovation as an operating executive and investor across the internet, mobile, restaurant, food tech and agtech sectors.

The Mixing Bowl released its first Indoor AgTech Landscape in September 2019. This is their first update, which you can download here, and their accompanying commentary.

Since the initial release of our Indoor AgTech Landscape in 2019, the compelling benefits of growing food in a controlled indoor environment have continued to garner tremendous attention and investment.

One of the intriguing aspects of indoor agriculture is that it is a microcosm of our food system. Whether within a greenhouse or a sunless (vertical farm) environment, this method of farming spans production to consumption, with many indoor operators marketing their produce to consumers as branded products. As we explore below, the indoor ag value chain reflects a number of the challenges and opportunities confronting our entire food system today: supply chain, safety, sustainability, and labor. Of course, the Covid-19 pandemic rippled through and impacted each aspect of that system, at times magnifying the challenges, and at others, accelerating change and growth.

Invest with Impact. Click here.

Our Indoor AgTech Landscape 2021 provides a snapshot of the technology and innovation ecosystem of the indoor food production value chain. The landscape spans component technology companies and providers of complete growing systems to actual tech-forward indoor farm operators. As before, the landscape is not meant to be exhaustive. While we track more than 1,300 companies in the sector, this landscape represents a subset and serves to highlight innovative players utilizing digital and information technology to enhance and optimize indoor food production at scale.

Supply chain & safety: Where does my food come from?

The pandemic highlighted the shortcomings of the existing supply chain and heightened consumer desires to know where their food comes from, how safely it was processed and packaged, and how far it has travelled to reach them. A key aspect of indoor farming is its built-in potential to respond to these and other challenges of the current food system.

Indoor farmers can locate their operations near distribution centers and consumers, reduce food miles and touch points, potentially deliver consistently fresher produce and reduce food waste, and claim the coveted “local” distinction. The decentralized system can also add resiliency to supply chains overly dependent on exclusive sources and imports.

Growing local has many forms. Greenhouse growers tend to locate their farms outside the metropolitan area while sunless growers may operate in urban centers, such as Sustenir Agriculture in Singapore and Growing Underground in London. Growers like Square Roots co-locate their indoor farms with their partner’s regional distribution centers, and Babylon deploys its micro-farms solution on site at healthcare and senior living facilities and universities. Recently, Infarm announced it was expanding beyond its growing-in-a-grocery store model, to include decentralized deployments of high-capacity “Growing Centers” across a number of cities. Additionally, the value of “growing local” might take on a much larger meaning if your country imports most of its produce from other countries; a number of the Gulf region countries have announced major indoor growing initiatives and projects with AeroFarms, Pure Harvest, and &ever to address the region’s food dependence on other countries.

Organic produce sales jumped to double digit growth in 2020 as consumers are increasingly mindful of the healthiness of their food. The additional safety concerns due to the pandemic only accelerated this trend. While not typically organic, crops produced in the protection of indoor farms are isolated from external sources of contamination and are often grown with few or no pesticides. Human touch points are reduced as supply chains shorten and production facilities become highly automated. Through the CEA Food Safety Coalition, the industry has recently taken steps to establish production standards with a goal to keep consumers safe from foodborne illness.

Indoor farmers market their products as local, fresh, consistent and clean. This story is resonating with consumers as the growers seem to be selling everything they can produce, with many reporting significant sales growth in 2020. The direct connection to consumer concerns is also a key part of their ability to sell their branded products at a premium, which has been critical to financial viability for some growers. This connection can also enable them to collapse the supply chain further, at least at smaller scales, through direct sales and creative business models, e.g., sunless grower Willo allows subscribers to have their own “personal vertical farm plot” and watch their plants grow online.

Sustainability: Is my food part of the problem or part of the solution?

Farming, as with most industries, has been under increasing pressure to operate more sustainably, and indoor growers, with their efficient use of resources, have rightfully incorporated sustainability prominently into their narratives.

We are well aware of the impacts of climate change, including greater variability in weather patterns and growing seasons. The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization projects that over the coming decades climate change will cause a decrease in global crop production through traditional farming practices, causing greater food insecurity. Indoor growing, which provides protection from the elements, consistent high yields per land area, and the ability to produce food year-round in diverse locations, including those unsuitable for traditional agriculture, can help mitigate this trend.

Water scarcity is projected to increase globally, presenting a national security issue and serious quality of life concerns. According to the World Bank, 70% of the global freshwater is used for agriculture. Indoor agriculture’s efficient use of water decreases use by more than 90% for the current crops under production. It is also common practice for greenhouses to capture rainwater and reuse drainage as does Agro Care, the Netherlands’ largest greenhouse tomato grower.

On the flip side, energy use, particularly in sunless facilities, is indoor growing’s sustainability challenge. Efficiency will continue to improve, but as recent analysis on indoor soilless farming from The Markets Institute at WWF indicated, there is an industry-wide opportunity to integrate alternative energy sources. Growers recognize this opportunity to decrease impact and improve bottom-line and are already utilizing alternative approaches such as cogeneration, geothermal sources, and waste heat networks. H2Orto tomatoes are grown in greenhouses heated with biogas generated hot water. Gotham Greens’ produce is grown in 100% renewable electricity-powered greenhouses, and Denmark’s Nordic Harvest will be running Europe’s largest indoor farm solely on wind power.

Labor: We’re still hiring!

There are labor challenges and opportunities throughout the food system value chain, and this couldn’t be more acute than on the farm. Farm operators—both in-field and indoor—find it difficult to attract labor for the physically demanding work. Even before the pandemic, the hardening of borders in Europe and the US created a shortage of farmworkers for both field and greenhouse production. In addition, grower and farm manager-level expertise is in short supply, exacerbated by an aging workforce and the rapid addition of new indoor facilities. While operators would like to see more trained candidates coming from university programs, they are also looking to technology and automation to relieve their labor challenges.

Automation of seedling production and post-harvest activities is already well established for most crops in indoor farming. In addition, the short growth cycle and contained habit of leafy greens lends them to mechanization. For example, the fully automated seed-through-harvest leafy green systems from Green Automation and Viscon have been deployed in major greenhouse operations like Pure Green Farms and Mucci. On the sunless side, Urban Crop Solutions has uniquely implemented automation in shipping containers, and Finland’s NetLed has developed a fully automated complete growing system. Note that many of the larger-scale sunless growers have developed their own technology stacks and have designed labor-saving automation into their systems. For example, Fifth Season has robotics deployed throughout the entire production process.

Despite numerous initiatives, the challenging daily crop care tasks and harvesting for certain crops (tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, and berries) have not yet been automated at scale. However, planned, near-term commercial deployments of de-leafing and harvesting robots offer the promise of significantly altering labor challenges. Software technologies, like those from Nitea and Hortikey address labor management, crop registration, yield prediction, and workflow/process management for the indoor sector and strive to improve operational efficiencies for a smaller workforce.

Technologies that provide, monitor, and control climate, light, water, and nutrients are already deployed in today’s sophisticated indoor growing facilities and are fundamental to maintaining optimal conditions in these complex environments. They also form the base for the next innovation layer, i.e., crop optimization and even autonomous control of the growing environment based on imaging and sensor platforms (like from Ecoation, iUNU, and 30MHz), data analysis, machine learning, digital twins and artificial intelligence. Recent events like the Autonomous Greenhouse Challenge have successfully explored the potential of AI to “drive horticultural productivity while reducing resource use and management complexity”. Emerging commercialized autonomous growing innovations, such as the Blue Radix Crop Controller and Priva’s Plantonomy, promise to extend and enhance the reach of available grower expertise, particularly in large and multi-site operations.

Where do we go from here?

Since we created our initial Indoor AgTech Landscape, there has been positive change and reason to be optimistic about the future. But, as with any evolving market and sector of innovation, it can be a bumpy ride. Some believe CEA is not the answer to our food problems because not everything can be economically grown indoors today. We see indoor ag as just one of the approaches that can help fix our food system and it should be applied when it makes sense. For example, tomatoes sold through retail are already more than likely grown in a greenhouse. Expect more crops to be grown indoors more economically with further advancements.

One aspect of our previous landscape was to increase awareness that, despite the fervor surrounding novel sunless farming, greenhouse growing was already well-established. Dutch greenhouse growers have demonstrated the viability of indoor growing with 50-plus years of experience and more acres “under glass than the size of Manhattan.” The recent public offering and $3 billion market cap of Kentucky-based greenhouse grower AppHarvest also clearly raised awareness! Other high-profile and expanding greenhouse growers, including BrightFarms and Gotham Greens, have also attracted large investments.

The question is often asked, “which is the better growing approach, sunless or greenhouse?”. There is no proverbial “silver bullet” for indoor farming. The answer is dictated by location and the problem you are trying to solve. A solution for the urban centers of Singapore, Hong Kong and Mumbai might not be the same as one deployed on the outskirts of Chicago.

Regardless of approach, starting any type of sizable tech-enabled indoor farm is capital intensive. A recent analysis from Agritecture indicates that it can range from $5 to $11 million dollars to build out a three-acre automated farm. Some of the huge, advanced greenhouse projects being built today can exceed $100 million. Given the capital requirements for these indoor farms, some question the opportunity for venture-level returns in the sector and suggest that it is better suited to investors in real assets. Still, more than $600 million was raised by the top 10 financings in 2020 as existing players vie for leadership and expand to underserved locales while a seemingly endless stream of new companies continue to enter the market.

Looking forward, indoor farming needs to address its energy and labor challenges. In particular, the sunless approach has work to do to bring its operating costs in line and achieve widespread profitability. Additionally, to further accelerate growth and the adoption of new technologies in both greenhouse and sunless environments, the sector needs to implement the sharing of data between systems. Waybeyond is one of the companies promoting open systems and APIs to achieve this goal.

As we stated in the beginning of this piece, the indoor ag value chain reflects some of the challenges and opportunities confronting our entire food system today: supply chain, safety, sustainability, and labor. Indoor agriculture has tremendous opportunity. While it is still early for this market sector overall, it can bring more precision and agility to where and how food is grown and distributed.

Eastern Kentucky Company Growing Local Economy By Growing Vegetables Year-Round

AppHarvest has created 300 jobs in Appalachia, an area not really known for growing tomatoes.

by GIL MCCLANAHAN

MOREHEAD, Ky. (WCHS) — Imagine growing fresh local tomatoes in the dead of winter. A company in Eastern Kentucky is using high-tech agriculture to grow vegetables indoors.

To View The Video, Please Click Here.

AppHarvest checks tomatoes growing inside the company's 60-acre indoor greenhouse.

(AppHarvest ) Courtesy Photo

AppHarvest opened in Rowan County, Ky. last October. They are growing more than just vegetables. They are growing the economy in an area that sorely needs it.

What's growing inside AppHarvest's 2.8-million square foot facility is capable of producing more food with less resources.

"For our first harvest to be on a day where there was a snowy mountainside could not have been any more timely. The fact that we are able to grow a great juicy flavorful tomato in the middle of January and February is what we have been working to accomplish," AppHarvest Founder and CEO Jonathan Webb said.

Webb said five months after opening its Morehead indoor farm facility, the company shipped more than a million beefsteak tomatoes to several major supermarket chains, including Kroger, Walmart and Publix. Those large bushels and bushels of tomatoes are grown using using the latest technology, no pesticides and with recycled water in a controlled environment using 90% less water than water used in open-field agriculture.

"We're just trying to get that plant a consistent environment year round with the right amount of light and the right amount of humidity and the right temperature just to grow, and the vines of our crops the tomato plant end up being 45 feet and we grow them vertically so that is how we can get so much more production," Webb said.

One of the company's more well-known investors is Martha Stewart.

"I said Martha, can I get five minutes and I told her what we are doing. She was like, look we need good healthy fruits and vegetables available at an affordable price. I love the region you are working in," Webb said.

A couple of weeks later, Webb met with Stewart at her New York office, and she decided to become an investor in the company. Some local restaurants are looking forward to the day when they can buy their vegetables locally from AppHarvest. Tim Kochendoerfer, Operating Partner with Reno's Roadhouse in Morehead, buys his vegetables from a company in Louisville.

"It will be another selling point to show that we are a local restaurant," Kochendoerfer said.

Webb points out AppHarvest is not trying to replace traditional family farming. "Absolutely not. We want to work hard with local farmers," he said.

Webb said by partnering with local farmers, more local produce can get on grocery store shelves, because last year 4 billion pounds of tomatoes were imported from Mexico.

"What we are working to replace is the imports from Mexico where you got children working for $5 a day using illegal chemical pesticides in the produce is sitting on a truck for 2-3000 miles," Webb said.

AppHarvest has already started influencing the next generation of farmers by donating high tech container farms to local schools. Students learn to grow crops, not in the traditional way, but inside recycled shipping containers. The containers can produce what is typically grown on 4 acres of land. Rowan County Senior High School was the second school to receive one. It arrived last fall.

"We sell that lettuce to our food service department and it's served in all of our cafeterias in the district," said Brandy Carver, Principal at Rowan County Senior High School.

"When we talk about food insecurity and young people going home hungry, what better way can we solve these problems by putting technology in the classroom. let kids learn, then let the kids take the food home with them and get healthy food in the cafeterias," Webb said.

AppHarvest has created 300 jobs in Appalachia, an area not really known for growing tomatoes. Local leaders believe the company will attract more business to the area.

"I fully expect in time we'll see more and more activity along that line like we do in all sectors," said Jason Slone, Executive Director of the Morehead-Rowan County Chamber of Commerce.

"We will eventually be at the top 25 grocers. Name a grocer. We've been getting phone calls from all of them," Webb said.

AppHarvest has two more indoor farming facilities under construction in Madison County, Ky., with a goal of building 10 more facilities like the one in Rowan County by the year 2025.

To find out more about AppHarvest click here.

Vertical Farms Nailed Tiny Salads. Now They Need To Feed The World

Vertical farming is finally growing up. But can it move from salad garnishes for the wealthy to sustainable produce for the masses?

Gartenfeld Island, in Berlin’s western suburb of Spandau, was once the bellows of Germany’s industrial revolution. It hosted Europe’s first high-rise factory and, until World War II, helped make Berlin, behind London and New York, the third-largest city on Earth.

Today’s Berlin is still a shell of its former self (there are over a hundred cities more populous), and the browbeaten brick buildings that now occupy Gartenfeld Island offer little in the way of grandeur. Flapping in the gloom of a grey November morning in 2020 is a sign which reads, in German, “The Last Days of Humanity”.

Yet inside one of these buildings is a company perched at agriculture’s avant-garde, part of the startup scene dragging Berlin back to its pioneering roots. In under eight years, Infarm has become a leader in vertical farming, an industry proponents say could help feed the world and address some of the environmental issues associated with traditional agriculture. Its staff wear not the plaid or twill of the field but the black, baggy uniform of the city’s hipsters.

Infarm has shipped over a thousand of its “farms” to shops and chefs across Europe (and a few in the US). These units, which look like jumbo vending machines, grow fresh greens and herbs in rows of trays fed by nutrient-rich water and lit by banks of tiny LEDs, each of which is more than ten times brighter than the regular bulb you’d find in your dining room. Shoppers pick the plants straight from the shelf where they’re growing.

Infarm crop science director, Pavlos Kalaitzoglou, in his Berlin lab

Credit Ériver Hijano

Gartenfeld Island, however, is home to something more spectacular. Here, in a former Siemens washing machine factory, stand four white, 18-metre-high “grow chambers”, controlled by software and served by robots. These are the company’s next generation of vertical farms: fully-automated, modular high-rises it hopes will scale the business to the next level. According to Infarm, each one of these new units uses 95 per cent less water, 99 per cent less space and 75 per cent less fertilizer than conventional land-based farming. This means higher yields, fresher produce and a smaller carbon footprint.

Agriculture is a £6 trillion global industry that has altered the face and lungs of the Earth for 12,000 years. But, unless we change our food systems, we’ll be in trouble. By 2050, the global population will be 9.7 billion, two billion more than today. Fifty-six per cent of us live in cities; by 2050 it will be 70 per cent. If the prosperity of megastates like India and China continues to soar, and our diets remain the same, we will need to double food production without razing the Amazon to do it. That sign on Gartenfeld Island might not be so alarmist.

Vertical farmers believe they are a part of the solution. Connected, precision systems have grown crops at hundreds of times the efficiency of soil-based agriculture. Located in or close to urban centres, they slash the farm-to-table time and eliminate logistics. New tech is allowing growers to tamper with light spectra and manipulate plant biology. Critics, however, question the role of vertical farms in our food future. They are towering lunchboxes for late capitalism, they argue – producing garnishes for the rich when it is the plates of the poor we must fill. Vertical farms already make money, and heavyweights including Amazon and SoftBank are investing in various companies in the hopes of cornering a market expected to be worth almost £10 billion in the next five to ten years. Infarm is leading that race in Europe. It has partnered with European retailers including Aldi, Carrefour and Marks & Spencer. In 2019 it penned a deal with Kroger, America’s largest supermarket chain. Venture capitalists have handed the firm a total of £228 million.

Not bad for a hare-brained experiment that started in a Berlin apartment.

An Infarm employee tends to a batch of seedlings in a special incubator

Credit Ériver Hijano

In 2011, a year before he moved to Berlin, Erez Galonska went off-grid. He grew up in a village in his native Israel, but the young nation was growing too, and farms made way for buildings. Soon the village was a town, and its inhabitants ever more disconnected from their natural surroundings.

Galonska’s father had studied agriculture, and the son had dreamed of recovering a connection with nature he felt he had lost. The search took him to the mountains of the Canary Islands, where he found a plot of land and got to work. He drank water from springs, drew energy from solar panels, and spent long hours farming produce he then sold or bartered at local markets.

When he met his now-wife Osnat Michaeli, “I traded it for love,” he says. “Love is stronger than anything.” In 2012, the couple, alongside Galonska’s brother Guy, who had studied Chinese medicine, moved to Berlin to work on a friend’s social media project. But the hunger for self-sufficiency remained. It was “a personal quest,” Michaeli says. “How we can be self-sufficient, live off the grid. Food is a big part of that journey.”

We meet at a Jewish restaurant in Berlin’s historic Gropius Bau art museum. It is mid-morning, and Covid-19 has cleared the tables. But a row of Infarm units whirs away quietly along one wall, producing basil, mint, wasabi rocket (a type of rocket leaf with the punchy flavour of wasabi), and other, more exotic herbs. Such produce was a pipedream for the three Infarm co-founders eight years ago. Growing crops when living on a tropical island was one thing. Doing it in a small apartment, located in the tumbledown Berlin neighbourhood of Neukölln, was quite another. Soon after moving from the Canaries, Erez Galonska typed “can you grow without soil” into Google.

Japan had taken to indoor farming in the 1970s, and this bore some helpful information on its techniques. The same was true of illegal cannabis growers, who swapped tips about hydroponics – growing with nutrient-packed water rather than soil – across subreddits.

Several trips to a DIY store later, the trio had what resembled a hydroponic farm. It was a big, chaotic Rube Goldberg machine, and it leaked everywhere. Growing wasn’t simply a case of switching on the lights and waiting. Brightness, nutrients, humidity, temperature – every tweaked metric resulted in an entirely different plant. One experiment yielded lettuce so fibrous it was like eating plastic. “We failed thousands of times,” Erez Galonska says.

Two of Infarm’s co-founders, Osnat Michaeli and Erez Galonska

Credit Ériver Hijano

Eventually, the team grew some tasty greens. They imagined future restaurant menus boasting of food grown “in-farm”, rather than simply made in-house, and founded Infarm in 2013. But there was a hitch: indoor-grown cannabis sells for around £1,000 per kilo. Lettuce for £1.20. Most of the early vertical farms required heaps of manual work and operated in the red. “It simply wasn’t a sustainable business model,” Erez Galonska says.

By 2014, they decided to roadshow their idea and shipped a 1955 Airstream trailer – a brushed-aluminium American icon – to Berlin. The trailer belonged to a former FBI agent, but it was conspicuous in a city of Volkswagens, caravans and Plattenbau buildings. Michaeli and the Galonska brothers transformed it into a mobile vertical farm, then pitched up at an urban garden collective in Berlin’s trendy Kreuzberg district. There they proselytised indoor farming to urban planners, food activists, architects and hackers, handing out salads and running workshops. Fresh, local food – even if it cost a little more – would entice a growing number of foodies who were interested in where their meals came from. The trailer cost nothing but petrol money to move, and emissions from the growing process itself were almost nil.

When the designer of a swanky hotel across town came by trailer, he asked if the team could install something similar in his restaurant. “That was really the trigger,” says Guy Galonska. “We rented a workshop and we got to develop a system for them.”

When they installed their first “farm” in a Berlin supermarket, VCs took notice and visited Infarm’s young founders at their Kreuzberg office-cum-kitchen, where they hosted dinner parties featuring Infarm crops. But a return on investment still seemed distant: some investors thought the farms were an art project. Maintaining locations manually was exhausting, and the team almost went bankrupt “two or three times,” Guy Galonska says. “I think all of us got a lot of white hair during that time,” he adds. “It was a very challenging thing to do.”

A €2 million grant from the European Union in 2016 helped. With it came deals to place Infarm units in supermarkets and restaurants across Germany. Managing them all would require something precise, connected and efficient. To become a sustainable business, Infarm would have to behave less like a farm, and more like a tech startup.

An Infarm kiosk in the Edeka Supermarket E Center in Berlin

Credit Ériver Hijano

For around 2,500 years after King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon gifted his wife some hanging gardens, little changed in the world of hydroponic farming. Asian farmers grew rice on giant, terraced paddies, and Aztecs built “chinampa” rigs that floated along the swamps of southern Mexico.

Life magazine published a drawing of stacked homes, each growing its own produce, in 1909, and the term “vertical farming” appeared six years later. The US Air Force fed hydroponically-grown veggies to its troops during World War II, and Nasa explored the tech as a solution for life off-planet. But vertical farming didn’t really capture public imagination until 1999, when Dickson Despommier, a Columbia University professor, devised a 30-storey skyscraper filled with farms. In 2010, Despommier published The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century, which has become the industry’s utopian testament.

“I had no expectations whatsoever that this would turn commercial,” Despommier says. “We just thought it was a good idea, because we didn’t see any other way out of stopping deforestation in favour of farming, and keeping the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere at a reasonable level. It turned out to be a crazy idea whose time has come.”

The vertical farming concept is simple: growing produce on vertically-stacked levels, rather than side by side in a field. Instead of the Sun, the vertical farm uses artificial light, and where there is ordinarily soil, growers use nutritious water or, in the case of “aeroponic” farms, an evenly-dispersed mist.

Vertical farms take up a vanishing amount of land compared to their conventional cousins. They use almost no water, don’t flush contaminating pesticides into the ecosystem, and can be built where people actually live. But, by and large, they have not functioned as businesses. Only the black-market margins of weed, and Japan’s high-income, high-import food ecosystem, have catered to profit. It costs hundreds of thousands of pounds to erect a mid-sized vertical farm, and energy use is prohibitively high.

Advances in technology are changing this. By bolting automation, machine learning and cloud-connected software on to vertical farms, firms can trim physical labour, increase capacity and maintain a dizzying range of cultivation variables. Infarm staff at a separate office to the new Berlin farm, located some 23km southeast of Spandau in the Tempelhof district, keep track of “plant recipe” settings at any one of the startup’s 1,220 in-store units, including CO2 levels, pH and growth cycles, via the company’s Farm Control Cloud Platform, a bit like a giant CCTV room. Machine learning finesses recipes, and keeps each plant as uniform as possible.

Inside the new vertical farm, trays of produce are tended by automated systems

Credit Ériver Hijano

Gartenfeld Island’s employees – mechanical and electrical engineers, software developers, crop scientists and biologists – get closer to the produce, but only just. They monitor via an iPad and feed crops into the building’s four massive grow chambers, or farms, each one about the height and width of two London buses, with ventilation systems that whoosh like a subdued turbine hall.

From there on in, robots do the hard work. Inside the farms, a robotic “plant retrieval system” – basically a tricked-out teddy picker – scoots up and down a perpendicular beam, plucking trays of plants in various stages of growth and shuffling them closer, or further, from LED lights at the summit. The firm claims this reduces service time by 88 per cent. A sliver of the window is the only way to see the device in-person: everything is hermetically sealed to keep out pests. “With automation, you invest once and then that price goes down over time,” says Orie Sofer, Infarm’s hardware lab lead. “With human labour, unfortunately, over time the price goes up.”

The number of crop plants varies depending on the produce, but there are usually just under 300 in a “farm” at any one time. Each farm yields the equivalent of 10,000 square metres of land and uses just five litres of water per kilo of food (traditional vegetable farming uses around 322 litres per kg).

Infarm is not alone in this revolution. AeroFarms, a Newark, New Jersey-based startup, feeds an aeroponic mist to roots that are separated from their leaves by a cloth. It’s most recent funding round was led by Ingka Group, the parent of Swedish furniture giant IKEA. New York’s Bowery Farming, like Infarm, focuses on automation and a proprietary dashboard called BoweryOS that, among other things, takes photos of crops in real-time for analysis. It’s £123 million in backing comes from investors including Singapore’s sovereign fund Temasek. Bowery CEO and founder Irving Fain believe his addressable market “is about a hundred billion dollars a year, just in the US, of crops that we think are good candidates for us to grow.”

Leading the vertical farming VC race is Plenty, a San Francisco-headquartered brand that has raised almost half a billion pounds in the capital since it was founded in 2013, including a 2020 Series D round led by Masayoshi Son’s $100 billion SoftBank Vision Fund. Plenty feeds its greens with water that trickles down six-metre-tall poles; infrared sensors pour data into an algorithm that nudges the plant’s growth recipe accordingly.

Plenty co-founder and chief science officer Nate Storey, who works at the company’s test farm in Wyoming, likens these deep-tech solutions to the tools that powered agriculture’s most recent revolution: “The tractor allowed farmers to be freed from constraints. Half of their land was dedicated to raising draft animals, and the tractor came along and freed them from a life where they were basically managing animals just so they could plough their land.”

For them, he says, automation is similar. “It allows us to get rid of the hardest work – the work that is unpleasant, the work [growers] don’t like to do – and focus on the work that really matters.”

Infarm kiosks inside the Beba restaurant in the Gropius Bau museum

Credit Ériver Hijano

Infarm differs from the competition on two fronts. The first is its focus on modular design: each component is compatible and scalable, like a giant, noisy LEGO set. Modularity makes it possible to install Infarm units anywhere in the world in a matter of weeks, no matter the size. That enables the company’s second USP: its business model. Infarm has no stores, selling produce instead via its remote units.

Clients tell Infarm which produce they want, and “create a schedule,” says Michaeli. “You buy the plants. Everything on the farm is controlled by Tempelhof. Everything that’s grown belongs to the client.” A chef may demand pesto that’s made from particular three-day-aged Greek and Italian basil, for example. Infarm can do that (Tim Raue, Berlin’s most famous chef, is a customer). “Everyone stops and asks about the farm,” one Berlin store manager says. “It’s great to have innovation here.”

Infarm has “two big advantages,” says Nicola Kerslake, founder of Contain Inc, a Nevada-based agtech financier. “One is that they’ve figured out how to do product onsite, which is really not very easy. And the other is that they have these great relationships with big purchasers like Marks & Spencer.”

“When you look at where the arms race is in this industry,” she continues, “it’s really been in two areas: How do I get hold of as much capital as possible, and how do I sign up the right partners? Having Marks & Spencer in your back pocket is really useful.”

It has helped encourage investors to open their chequebooks. Hiro Tamura, a partner at London VC firm Atomico, first met Infarm’s founding trio in 2018. A year later he led its £75 million Series B round. “They could roll these things out,” he says. “They worked, and they didn’t need some industrial-sized warehouse to do it. I didn’t lean in, I fell into the rabbit hole. And it was incredible. I was like, wow, these guys are thinking about time and speed to market modularity.”

Infarm ploughs a chunk of its revenue back into research. In a mezzanine-level lab sitting above the farms at Gartenfeld Island, a dozen white-coated analysts conduct tests on herbs to a soundtrack of Ariana Grande, measuring crop sugar levels, acidity, vitamins, toxicity, antioxidants and more. Via a process of phenotyping – the study of organisms’ characteristics relative to their environment – they hope to create more flavourful plants, or new tastes altogether.

“It’s not just about the hardware,” Kerslake explains. “It’s about how the hardware interacts with the rest of your farm system. And we’re starting to see a lot more sophistication on that front because the AI programs these companies started three or four years ago are now starting to bear fruit.”

Infarm’s results are high-quality: juicy lettuce, wasabi rocket that kicks, and basil that’s far more fragrant than the budget variety. “The end goal with almost everything that we’re doing is developing some sort of playbook, some sort of modular and standardised system, that we can then copy-paste to wherever we go,” says Pavlos Kalaitzoglou, Infarm’s director of plant science. Across from the lab, tomatoes and shiitake mushrooms grow in wine cellar-size chambers. They are living proof of how the firm is looking to diversify from herbs and leafy greens, whose low energy and water requirements make them the staple crop of every vertical farming startup today.

Rows of LED-illuminated produce inside one of Infarm’s four massive new grow chambers

Credit Ériver Hijano

We are in danger of farming the planet to death. Agriculture already occupies 40 per cent of all liveable land on Earth, and food production causes a quarter of all greenhouse gases. An area the size of Scotland disappears from tropical rainforests, responsible for up to a quarter of land photosynthesis, each year. Clearing more trees to feed our spiralling population will not help.

“We need to go back to the drawing board and rethink which avenues we can environmentally afford to pursue,” says Nicola Cannon, a professor at the Royal Agricultural University in Cirencester. Nitrogen fertiliser is particularly harmful to the environment, Cannon adds, “and has led us to adopt systems which have grossly exceeded the planetary boundaries.”

Current food systems are wildly inefficient: waste accounts for 25 per cent of all calories. And yet, almost a billion people suffer from hunger worldwide. These are not issues vertical farming will solve, critics, argue. Going local does little beyond satisfying consumers.

Energy is another tricky issue. Ninety per cent of Infarm’s electricity today is renewable, and it wants to reach zero emissions in the next few years. But this doesn’t factor in the environmental cost of building a steel-and-cement facility.

“Vertical farms are a round-off error to the round-off error in terms of contributing to the big levers out there,” Jonathan Foley, an environmental scientist based in Minneapolis, says. “Like most technologies that are getting a lot of venture capital and which come from Silicon Valley kind of thinking, it’s being massively overhyped at the cost of real solutions. There’s an opportunity cost to put all this technology, money and renewable energy – that could be used for other things that we need energy for – into growing arugula for rich people at $10 an ounce.”

More than half the world’s food energy comes from its three “mega-crops”: wheat, corn and rice. They require wind, seasons and micronutrients that vertical farms are unable to replicate today. These are the crops that can prevent famine in Somalia, Bangladesh or Bolivia – not lettuce. “Vertical farms are growing the edge of the plate, not the centre of the plate,” Foley says.

But Despommier says it’s too soon to criticise the young industry for not addressing issues such as crop diversity. “What you’re really seeing is a rush towards profitability to get their feet wet, and to get their ledgers in the black and to pay off their investors, before they start diversifying,” he says.

“In a world where you think that land is unlimited and that resources are unlimited, indoor farming would be nonsensical,” Plenty co-founder Storey says. “As crazy as it seems to replace the Sun with electricity, it makes sense today. And it really makes more and more sense as time goes on.”

Much of the hope vested in vertical farms rests on the light-emitting diode. This tiny bead of light is the industry’s packhorse: it is a farm’s biggest financial layout and the nucleus of its most exciting advances. Modern LEDs are nothing like the ones that powered your childhood TV. They’ve progressed at such a rate, in fact, that they’ve developed their own law to adhere to: “Haitz’s Law”. Each decade, their cost drops by a factor of ten, while the light they generate leaps by a factor of 20.

That curve will eventually plateau, experts say. But not before LEDs improve enough to allow vertical farms to profit from food closer to the middle of the plate. Infarm’s current smart LED set-up is over 50 per cent more efficient than the one that lit its first farms. Haitz’s Law has helped some companies experiment in growing potatoes, which require far more energy and water than leafy greens. Turning profit from a crop that delivers the highest calories per acre would be momentous for the industry.

The cutting edge of LED technology today is smart sensors that can regulate the brightness and spectrum of light to replicate growing outdoors – or enhance it. Much of the planet’s first flora grew only in the ocean, which looks blue because it absorbs blue light at least.

Photosynthesis, therefore, occurs best between the blue and red light spectra. By tailoring LEDs to emit only these colours, or by dimming at intervals meant to mirror a plant’s natural cycle, vertical farmers can further reduce their energy burden – like stripping a road car to its bare bones so it can drive faster.

Recent discoveries have been more surprising. Strawberries, for example, react particularly well to green light. Some spectra can increase vitamin C in concentrated fruits like kiwis, while others extend shelf-lives by almost a week. In the future, says Fei Jia, of LED firm Heliospectra, growers “can get feedback from the lighting and the plants themselves on how the lighting should be applied… to further improve the consistency of the crop quality.”

“If you judge it from what you have today, you understand what [critics] are saying,” Guy Galonska says. “How can you grow rice and wheat and save the world? And they are right. But they can’t see ten years ahead: they can’t see all the different trends that are going to support that revolution.”

Other technological advances are helping agriculture in different ways. Drones and sensors help map and streamline growing. Drip irrigation dramatically reduces the burden on dwindling water supplies. Circular production – where waste products from one process contribute to fuelling another – is becoming more commonplace, especially in livestock farming. Cell-grown or insect-based meat (or vegetarianism) will reduce our reliance on livestock, which consume 45 per cent of the planet’s crops. Infarm, and the broader vertical farm cohort, may not be saving the world today. But it wants to build taller farms, place them in public buildings like schools, and teach people the value of fresh, healthy vegetables. If 70 per cent of us are to live in cities, then cities “can become these communities of growing,” says Erez Galonska.

Ultimately, Infarm wants to build a network of tens of thousands of automated farms, each one pumping streams of data back into a giant AI system in Berlin. This “brain”, as Galonska calls it, will pour that information into algorithms to generate better food at lower costs, each new yield shaving fractions from the water, energy and nutrients required. Then, Infarm could become something closer to the dream Galonska left behind in the Canaries: truly self-sufficient.

It’s a long way from the leaky, DIY gadget he and his co-founders built in their front room. “The way the world is going now, it’s very clear to everyone it’s running in the wrong direction,” Galonska says. “We definitely believe in the power of collaboration: bringing those outside-the-box thoughts to create a new system that will generate more food, better food, much more sustainably, and help to heal the planet – because that’s the main issue on the table.”

Agritech: Precision Farming With AI, IoT and 5G

For a company that grows and delivers vegetables, Boomgrow Productions Sdn Bhd’s office is nothing like a farm, or even a vertical farm. Where farms are bedecked with wheelbarrows, spades and hoes, Boomgrow’s floor plan is akin to a co-working space with a communal island table, several cubicles, comfortable armchairs, a cosy hanging rattan chair and a glass-walled conference room in the middle

Image from: Photo by Mohd Izwan Mohd Nazam/The Edge

For a company that grows and delivers vegetables, Boomgrow Productions Sdn Bhd’s office is nothing like a farm, or even a vertical farm.

Where farms are bedecked with wheelbarrows, spades and hoes, Boomgrow’s floor plan is akin to a co-working space with a communal island table, several cubicles, comfortable armchairs, a cosy hanging rattan chair and a glass-walled conference room in the middle.

At a corner, propped up along a walkway leading to a rectangular chamber fitted with grow lights, are rows of support stilts with hydroponic planters developed in-house and an agricultural technologist perched on a chair, perusing data. “This is where some of the R&D work happens,” says Jay Dasen, co-founder of the agritech start-up.

But there is a larger farm where most of the work behind this high-tech initiative is executed. Located a stone’s throw from the city centre in Ampang is a 40ft repurposed shipping container outfitted with perception technologies and artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities that mimic the ideal environment to produce more than 50,000kg of vegetables a year.

Stacked in vertical layers, Boomgrow’s vegetables are grown under artificial lights with Internet of Things (IoT) sensors to detect everything from leaf discolouration to nitrate composition. This is coupled with AI and machine learning algorithms.

Boomgrow is the country’s first 5G-connected vertical farm. With the low latency and larger bandwidth technology, the start-up is able to monitor production in real time as well as maintain key parameters, such as temperature and humidity, to ensure optimal growth conditions.

When Jay and her co-founders, K Muralidesan and Shan Palani, embarked on this initiative six years ago, Boomgrow was nowhere near what it is today.

The three founders got together hoping to do their part in building a more sustainable future. “I’ve spent years advising small and large companies on sustainability, environmental and social governance disclosures. I even embarked on a doctorate in sustainability disclosure and governance,” says Jay.

“But I felt a deep sense of disconnect because while I saw companies evolving in terms of policies, processes and procedures towards sustainability, the people in those organisations were not transforming. Sustainability is almost like this white noise in the background. We know it’s important and we know it needs to be done, but we don’t really know how to integrate it into our lives.

“That disconnect really troubled me. When we started Boomgrow, it wasn’t a linear journey. Boomgrow is something that came out of meaningful conversations and many years of research.”

Shan, on the other hand, was an architect who developed a taste for sustainable designs when he was designing modular structures with minimal impact on their surroundings between regular projects. “It was great doing that kind of work. But I was getting very dissatisfied because the projects were customer-driven, which meant I would end up having debates about trivial stuff such as the colour of wall tiles,” he says.

As for Murali, the impetus to start Boomgrow came from having lived overseas — while working in capital markets and financial services — where quality and nutritious produce was easily available.

Ultimately, they concluded that the best way to work towards their shared sustainability goals was to address the imminent problem of food shortage.

“By 2050, the world’s population is expected to grow to 9.7 billion people, two-thirds of whom will be in Asia-Pacific. Feeding all those people will definitely be a huge challenge,” says Jay.

“The current agricultural practice is not built for resilience, but efficiency. So, when you think of farming, you think of vast tracts of land located far away from where you live or shop.

“The only way we could reimagine or rethink that was to make sure the food is located closer to consumers, with a hyperlocal strategy that is traceable and transparent, and also free of pesticides.”

Having little experience in growing anything, it took them a while to figure out the best mechanism to achieve their goal. “After we started working on prototypes, we realised that the tropics are not designed for certain types of farming,” says Jay.

“And then, there is the problem of harmful chemicals and pesticides everywhere, which has become a necessity for farmers to protect their crops because of the unpredictable climate. We went through many iterations … when we started, we used to farm in little boxes, but that didn’t quite work out.”

They explored different methodologies, from hydroponics to aquaponics, and even started growing outdoors. But they lost a lot of crops when a heat wave struck.

That was when they started exploring more effective ways to farm. “How can we protect the farm from terrible torrential rains, plant 365 days a year and keep prices affordable? It took us five years to answer these questions,” says Jay.

Even though farmers all over the world currently produce more than enough food to feed everyone, 820 million people — roughly 11% of the global population — did not have enough to eat in 2018, according to the World Health Organization. Concurrently, food safety and quality concerns are rising, with more consumers opting for organically produced food as well as safe foods, out of fear of harmful synthetic fertilisers, pesticides, herbicides and fungicides.

According to ResearchAndMarkets.com, consumer demand for global organic fruit and vegetables was valued at US$19.16 billion in 2019 and is anticipated to expand at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.5% by 2026.

Meanwhile, the precision farming market was estimated to be US$7 billion in 2020 and is projected to reach US$12.8 billion by 2025, at a CAGR of 12.7% between 2020 and 2025, states MarketsandMarkets Research Pte Ltd.

Malaysia currently imports RM1 billion worth of leafy vegetables from countries such as Australia, China and Japan. Sourcing good and safe food from local suppliers not only benefits the country from a food security standpoint but also improves Malaysia’s competitive advantage, says Jay.

Unlike organic farming — which is still a soil-based method — tech-enabled precision farming has the advantage of catering for increasing demand and optimum crop production with the limited resources available. Moreover, changing weather patterns due to global warming encourage the adoption of advanced farming technologies to enhance farm productivity and crop yield.

Boomgrow’s model does not require the acres of land that traditional farms need, Jay emphasises. With indoor farms, the company promises a year-round harvest, undisturbed by climate and which uses 95% less water, land and fuel to operate.

Traditional farming is back-breaking labour. But with precision technology, farmers can spend less time on the farm and more on doing other things to develop their business, she says.

Boomgrow has secured more than RM300,000 in funding via technology and innovation grants from SME Corporation Malaysia, PlaTCOM Ventures and Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation, and is on track to build the country’s largest indoor farms.

Image from: Boomgrow

The company got its chance to showcase the strength of its smart technology when Telekom Malaysia Bhd (TM) approached it to be a part of the telco’s Smart Agriculture cluster in Langkawi last October.

“5G makes it faster for us to process the multiple data streams that we need because we collect data for machine learning, and then AI helps us to make decisions faster,” Jay explains.

“We manage the farm using machines to study inputs like water and electricity and even measure humidity. All the farm’s produce is lab-tested and we can keep our promise that there are no pesticides, herbicides or any preserving chemicals. We follow the food safety standards set by the EU, where nitrate accumulation in plant tissues is a big issue.”

With TM’s 5G technology and Boomgrow’s patent-pending technology, the latter is able to grow vegetables like the staple Asian greens and highland crops such as butterhead and romaine lettuce as well as kale and mint. While the company is able to grow more than 30 varieties of leafy greens, it has decided to stick to a selection of crops that is most in demand to reduce waste, says Jay.

As it stands, shipping containers are the best fit for the company’s current endeavour as containerised modular farms are the simplest means of bringing better food to local communities. However, it is also developing a blueprint to house farms in buildings, she says.

Since the showcase, Boomgrow has started to supply its crops to various hotels in Langkawi. It rolled out its e-commerce platform last year after the Movement Control Order was imposed.

“On our website, we promise to deliver the greens within six hours of harvest. But actually, you could get them way earlier. We harvest the morning after the orders come in and the vegetables are delivered on the same day,” says Jay.

Being mindful of Boomgrow’s carbon footprint, orders are organised and scheduled according to consumers’ localities, she points out. “We don’t want our delivery partners zipping everywhere, so we stagger the orders based on where consumers live.

“For example, all deliveries to Petaling Jaya happen on Thursdays, but the vegetables are harvested that morning. They are not harvested a week before, three days before or the night before. This is what it means to be hyperlocal. We want to deliver produce at its freshest and most nutritious state.”

Plans to expand regionally are also underway, once Boomgrow’s fundraising exercise is complete, says Jay. “Most probably, this will only happen when the Covid-19 pandemic ends.”

To gain the knowledge they have today, the team had to “unlearn” everything they knew and take up new skills to figure what would work best for their business, says Jay. “All this wouldn’t have been possible if we had not experimented with smart cameras to monitor the condition of our produce,” she laughs.

2021 GLASE Webinar Series

The production of high nutrient density crops in controlled environments (such as greenhouses and plant factories) allows for high density, local, year-round food production

Urban CEA: Optimizing Plant Quality,

Economic And Environmental Outcomes

Date: February 25, 2021

Time: 2 p.m. - 3 p.m. EDT

Presented by: Dr. Neil Mattson (Cornell University)

Click Here To Register

The production of high nutrient density crops in controlled environments (such as greenhouses and plant factories) allows for high density, local, year-round food production. Mattson leads a National Science Foundation project that seeks to better understand the benefits and constraints of urban CEA including: economics, natural resource use, carbon footprint, and nutrition. Mattson will discuss research that seeks to optimize crop performance, nutrition, and resource use through strategic LED lighting and CO2 supplementation. Finally, Mattson will discuss efforts of the NSF project to define workforce development needs by the nascent urban CEA industry and a new USDA workforce development project to expand training opportunities in CEA for 2-year colleges and lifelong learners.

Special thanks to our Industry partners

Join today

If you have any questions or would like to know more about GLASE,

please contact its executive director

Erico Mattos at em796@cornell.edu

Take A Virtual Tour of The New CEA Center

“What OHCEAC is unique about is that we are integrative, interdisciplinary, and inclusive team conducting collaborative research to respond to CEA stakeholder needs

18-02-2021 | Urban Ag News

US, Ohio- Dr. Chieri Kubota, the Director of the new center focusing on controlled environment agriculture and protected cultivation hosted this event to introduces the programs and membership at The Ohio State University.

“What OHCEAC is unique about is that we are integrative, interdisciplinary, and inclusive team conducting collaborative research to respond to CEA stakeholder needs. Our focus inclusively covers various production systems and crop types. We use the terminology of CEA as having a very broad meaning including soil-bassed or soilless systems under various types of climate control or modification structures.”

Source and Photo Courtesy of Urban Ag News

Vertical Farming ‘At a Crossroads’

Although growing crops all year round with Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) has been proposed as a method to localize food production and increase resilience against extreme climate events, the efficiency and limitations of this strategy need to be evaluated for each location

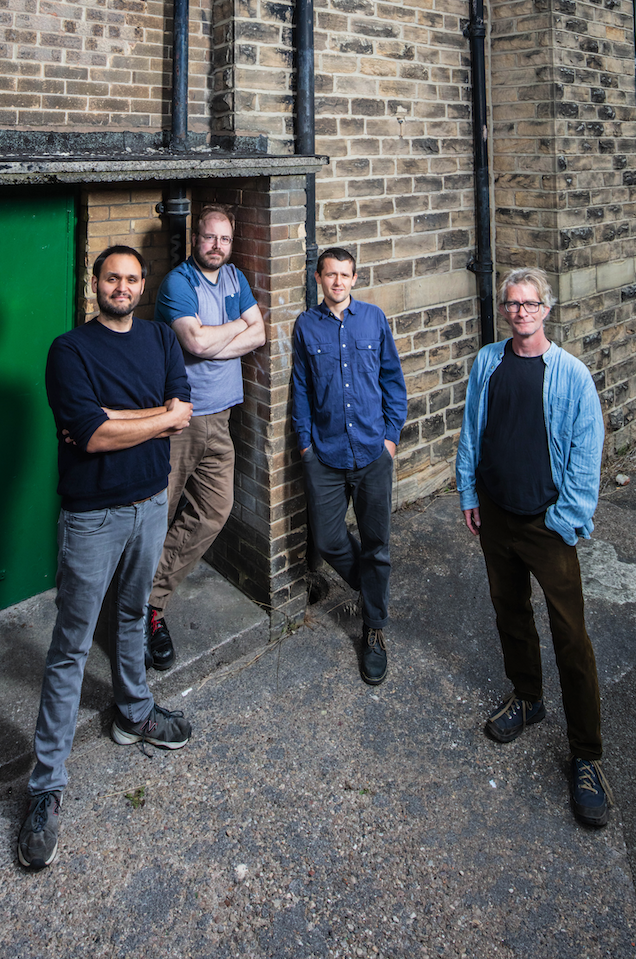

Building the right business model to balance resource usage with socio-economic conditions is crucial to capturing new markets, say speakers ahead of Agri-TechE event

Image from: Fruitnet

Although growing crops all year round with Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) has been proposed as a method to localize food production and increase resilience against extreme climate events, the efficiency and limitations of this strategy need to be evaluated for each location.

That is the conclusion of research by Luuk Graamans of Wageningen University & Research, a speaker at the upcoming Agri-TechE event on CEA, which takes place on 25 February.

His research shows that integration with urban energy infrastructure can make vertical farms more viable. Graamans’ research around the modelling of vertical farms shows that these systems are able to achieve higher resource use efficiencies, compared to more traditional food production, except when it comes to electricity.

Vertical farms, therefore, need to offer additional benefits to offset this increased energy use, Graamans said. One example his team has investigated is whether vertical farms could also provide heat.

“We investigated if vertical farms could provide not just food for people living in densely populated areas and also heat their homes using waste heat. We found that CEA can contribute to stabilizing the increasingly complex energy grid.”

Diversification

This balance between complex factors both within the growing environment and wider socio-economic conditions means that the rapidly growing CEA industry is beginning to diversify with different business models emerging.

Jack Farmer is CSO at vertical producer LettUs Grow, which recently launched its Drop & Grow growing units, offering a complete farming solution in a shipping container.

He believes everyone in the vertical farming space is going to hit a crossroads. “Vertical farming, with its focus on higher value and higher density crops, is effectively a subset of the broader horticultural sector,” he said.

"All the players in the vertical farming space are facing a choice – to scale vertically and try to capture as much value in that specific space, or to diversify and take their technology expertise broader.”

LettUs Grow is focussed on being the leading technology provider in containerised farming, and its smaller ‘Drop & Grow: 24’ container is mainly focussed on people entering the horticultural space.

Opportunities in retail

“This year is looking really exciting,” he said. “Supermarkets are investing to ensure a sustainable source of food production in the UK, which is what CEA provides. We’re also seeing a growth in ‘experiential’ food and retail and that’s also where we see our Drop & Grow container farm fitting in.”

Kate Hofman, CEO, GrowUp agrees. The company launched the UK’s first commercial-scale vertical farm in 2014.

“It will be really interesting to see how the foodservice world recovers after lockdown – the rough numbers are that supermarket trade was up at least 11 per cent in the last year – so retail still looks like a really good direction to go in.

“If we want to have an impact on the food system in the UK and change it for the better, we’re committed to partnering with those big retailers to help them deliver on their sustainability and values-driven goals.

“Our focus is very much as a salad grower that grows a fantastic product that everyone will want to buy. And we’re focussed on bringing down the cost of sustainable food, which means doing it at a big enough scale to gain the economies of production that are needed to be able to sell at everyday prices.”

Making the Numbers Add Up

The economics are an important part of the discussion. Recent investment in the sector has come from the Middle East, and other locations, where abundant solar power and scarce resources are driving interest in CEA. Graamans’ research has revealed a number of scenarios where CEA has a strong business case.

For the UK, CEA should be seen as a continuum from glasshouses to vertical farming, he believes. “Greenhouses can incorporate the technologies from vertical farms to increase climate control and to enhance their performance under specific climates."

It is this aspect that is grabbing the attention of conventional fresh produce growers in open field and covered crop production.

A Blended Approach

James Green, director of agriculture at G’s, thinks combining different growing methods is the way forward. “There’s a balance in all of these systems between energy costs for lighting, energy costs for cooling, costs of nutrient supply, and then transportation and the supply and demand. At the end of the day, sunshine is pretty cheap and it comes up every day.

“I think a blended approach, where you’re getting as much benefit as you can from nature but you’re supplementing it and controlling the growth conditions, is what we are aiming for, rather than the fully artificially lit ‘vertical farming’.”

Graamans, Farmer and Hofman will join a discussion with conventional vegetable producers, vertical farmers and technology providers at the Agri-TechE event ‘Controlled Environment Agriculture is growing up’ on 25 February 2021.

Smart Agriculture Startup Bowery Farming Hires A Google Veteran As CTO

The hire comes after a year of accelerated growth at Bowery, with retail sales at outlets like Whole Foods rising 600% and e-commerce sales via Amazon and others increasing fourfold, the company says, while declining to disclose its actual sales or production figures.

One goal of high-tech indoor farming startup Bowery Farming is to use artificial intelligence and machine learning to enhance its crop yields and reduce costs. So the five-year-old Manhattan-based company has hired Google and Samsung veteran Injong Rhee as its new chief technology officer.

Rhee, who was previously Internet of Things VP at Google and chief technologist at Samsung Mobile, will focus on improving Bowery’s computer-vision system and other sensors that analyze when plants need water and nutrients, while also looking to apply the company’s accumulated historical data to new problems.

Bowery grow room near Baltimore

“Agriculture is sitting at the crux of the world’s most challenging problems like food shortages, climate change, water shortages, a lack of arable space,” Rhee tells Fortune about his decision to join the startup. “These are very challenging problems, and all of these are relevant to what Bowery tackles every day. Any advances we make here lead to a better world.”

There’s also the matter of the kale, Rhee adds.

Bowery so far has focused on growing and selling green leafy vegetables like lettuce, arugula, and kale, though it aims to add other categories of produce soon. “It was an eye-popping experience,” Rhee says of his first time trying Bowery’s kale. “How can it be so sweet and so crunchy. That was amazing.”

The hire comes after a year of accelerated growth at Bowery, with retail sales at outlets like Whole Foods rising 600% and e-commerce sales via Amazon and others increasing fourfold, the company says, while declining to disclose its actual sales or production figures. With two large warehouse-size farms in operation, in New Jersey and Maryland, Bowery is on the verge of opening its third indoor growing center in Bethlehem, Pa. The startup claims its high-tech methods, though more expensive than growing outdoors, create farms that are more than 100 times as productive per square foot as traditional outdoor farms.

“COVID was an accelerator of trends,” Bowery CEO and founder Irving Fain says. The pandemic disrupted food supply chains stretching across the globe, giving an advantage to Bowery, which sells its produce within just a few hundred miles of each farm, he says. “That amplified and accelerated a trend towards simplifying supply chains, and creating a surety of supply.”

But Bowery also faces a host of competitors, from other indoor farming startups like AeroFarms and Gotham Greens, to more traditional ag companies like John Deere and Bayer’s Monsanto, all fueling a movement toward precision farming. If one-quarter of farms worldwide adopted precision agriculture using A.I. and other data-crunching methods by 2030, farmers’ annual expenses would decline by $100 billion, or as much as 4% of the sector’s total expenses, while saving water and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, a recent study by McKinsey found.

Rhee spent 15 years as a professor of computer science at North Carolina State University, where he helped develop core Internet standards for transporting data at high speeds. He joined Samsung in 2011 where he helped lead a wide range of projects including the Bixby digital assistant, Knox security app, and Samsung Pay mobile payments service. He moved to Google in 2018 as an entrepreneur-in-residence to focus on Internet of Things projects.

Bowery has raised over $170 million in venture capital from a mix of tech figures like Amazon consumer CEO Jeff Wilke and Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi, well-known restaurateurs such as Tom Colicchio and David Barber, and venture capital firms including Temasek, GV, and General Catalyst.

Bringing The Future To life In Abu Dhabi

A cluster of shipping containers in a city centre is about the last place you’d expect to find salad growing. Yet for the past year, vertical farming startup Madar Farms has been using this site in Masdar City, Abu Dhabi, to grow leafy green vegetables using 95 per cent less water than traditional agriculture

Amid the deserts of Abu Dhabi, a new wave of entrepreneurs and innovators are sowing the seeds of a more sustainable future.

Image from: Wired

A cluster of shipping containers in a city centre is about the last place you’d expect to find salad growing. Yet for the past year, vertical farming startup Madar Farms has been using this site in Masdar City, Abu Dhabi, to grow leafy green vegetables using 95 per cent less water than traditional agriculture.

Madar Farms is one of a number of agtech startups benefitting from a package of incentives from the Abu Dhabi Investment Office (ADIO) aimed at spurring the development of innovative solutions for sustainable desert farming. The partnership is part of ADIO’s $545 million Innovation Programme dedicated to supporting companies in high-growth areas.

“Abu Dhabi is pressing ahead with our mission to ‘turn the desert green’,” explained H.E. Dr. Tariq Bin Hendi, Director General of ADIO, in November 2020. “We have created an environment where innovative ideas can flourish and the companies we partnered with earlier this year are already propelling the growth of Abu Dhabi’s 24,000 farms.”

The pandemic has made food supply a critical concern across the entire world, combined with the effects of population growth and climate change, which are stretching the capacity of less efficient traditional farming methods. Abu Dhabi’s pioneering efforts to drive agricultural innovation have been gathering pace and look set to produce cutting-edge solutions addressing food security challenges.

Beyond work supporting the application of novel agricultural technologies, Abu Dhabi is also investing in foundational research and development to tackle this growing problem.

In December, the emirate’s recently created Advanced Technology Research Council [ATRC], responsible for defining Abu Dhabi’s R&D strategy and establishing the emirate and the wider UAE as a desired home for advanced technology talent, announced a four-year competition with a $15 million prize for food security research. Launched through ATRC’s project management arm, ASPIRE, in partnership with the XPRIZE Foundation, the award will support the development of environmentally-friendly protein alternatives with the aim to "feed the next billion".

Image from: Madar Farms

Global Challenges, Local Solutions

Food security is far from the only global challenge on the emirate’s R&D menu. In November 2020, the ATRC announced the launch of the Technology Innovation Institute (TII), created to support applied research on the key priorities of quantum research, autonomous robotics, cryptography, advanced materials, digital security, directed energy and secure systems.

“The technologies under development at TII are not randomly selected,” explains the centre’s secretary general Faisal Al Bannai. “This research will complement fields that are of national importance. Quantum technologies and cryptography are crucial for protecting critical infrastructure, for example, while directed energy research has use-cases in healthcare. But beyond this, the technologies and research of TII will have global impact.”

Future research directions will be developed by the ATRC’s ASPIRE pillar, in collaboration with stakeholders from across a diverse range of industry sectors.

“ASPIRE defines the problem, sets milestones, and monitors the progress of the projects,” Al Bannai says. “It will also make impactful decisions related to the selection of research partners and the allocation of funding, to ensure that their R&D priorities align with Abu Dhabi and the UAE's broader development goals.”

Image from: Agritecture

Nurturing Next-Generation Talent

To address these challenges, ATRC’s first initiative is a talent development programme, NexTech, which has begun the recruitment of 125 local researchers, who will work across 31 projects in collaboration with 23 world-leading research centres.

Alongside universities and research institutes from across the US, the UK, Europe and South America, these partners include Abu Dhabi’s own Khalifa University, and Mohamed bin Zayed University of Artificial Intelligence, the world’s first graduate-level institute focused on artificial intelligence.

“Our aim is to up skill the researchers by allowing them to work across various disciplines in collaboration with world-renowned experts,” Al Bannai says.

Beyond academic collaborators, TII is also working with a number of industry partners, such as hyperloop technology company, Virgin Hyperloop. Such industry collaborations, Al Bannai points out, are essential to ensuring that TII research directly tackles relevant problems and has a smooth path to commercial impact in order to fuel job creation across the UAE.

“By engaging with top global talent, universities and research institutions and industry players, TII connects an intellectual community,” he says. “This reinforces Abu Dhabi and the UAE’s status as a global hub for innovation and contributes to the broader development of the knowledge-based economy.”

US - OHIO: Thinking And Growing Inside The Box

A brother-sister team has taken the mechanics of farming out of the field and into a freight container. “We are growing beautiful plants without the sun; there’s no soil, and so it’s all a closed-loop water system,” Britt Decker, co-owner of Fifth Season FARM, said

A brother-sister team has taken the mechanics of farming out of the field and into a freight container.

“We are growing beautiful plants without the sun; there’s no soil, and so it’s all a closed-loop water system,” Britt Decker, co-owner of Fifth Season FARM, said. “We use non-GMO seeds, completely free of herbicides and pesticides, so the product is really, really clean. In fact, we recommend people don’t even wash it, because there’s no reason to.”

Fifth Season FARM is unique in many ways; the 3-acre hydroponic farm is contained in a 320-square-foot freight container that sits along 120 S. Main St. in Piqua, with everything from varying varities of lettuce, to radishes, to kale and even flowers in a climate-controlled smart farm that allows Decker and his sister, Laura Jackson, to turn crops in a six- to eight-week cycle. The crops spend 18 hours in “daytime” every day, and the farm uses 90% less water than traditional farming.

“It’s tricky because we’re completely controlling the environment in here. It’s kind of a laboratory more than a farm,” Decker said. “I think there’s about 50 of them around the world right now. These are really international, and they’re perfect for places that are food deserts where they can’t grow food because of climate or other reasons. It gives them a way to grow food in the middle of nowhere.”

Image from: Sidney Daily News

Decker and Jackson, along with their brother Bill Decker, also do traditional farming and grow corn, wheat and soybeans, but Decker said they were looking for a new venture that would help lead them to a healthier lifestyle and learn something new.

“Just with the whole local food movement becoming more and more important and food traceability, we just thought it would be a great thing to bring to our community to help everyone have a healthier lifestyle,” Decker said. “People love food that’s grown right in their hometown and the shelf-life on it, when you get it home, is remarkable. It’ll keep for two weeks.”

Image from: AgFunder News

Currently, Decker and Jackson are growing a half-dozen variety of specialty lettuces that include arugula, butterhead and romaine, as well as specialty greens like kale and Swiss chard, and even radishes and flowers. They received their freight container at the end of July and set up their indoor farm over two weeks; while the farm has been in operation for less than six months, Decker says that they’re growing beautiful product.

They have also started growing micro-greens, said Decker. Micro-greens are immature plants which are 1 to 3 inches tall and are in a 5-inch by 5-inch container.